Mexico, California and Arizona/Chapter 8

VIII.

THE QUESTION OF MONEY, AND SHOPPING.

I.

It is perhaps thought that the work of improvement is to be effected entirely from without, the Mexican himself remaining passive, and allowing everything to be done for him. The view is supported by the extent to which the business of the country is already in the hands of foreigners. The bankers and manufacturers are English. The Germans control hardware and "fancy goods." French and Italians keep the hotels and restaurants; Spaniards the small groceries and pawn-shops, and deal in the products of the country. These latter have a repute for somewhat Jewish style of thrift. They are enterprising as administrators of haciendas, and often marry the proprietors' daughters, and possess themselves on their own account of the properties to which they were sent as agents. Whether it be due to such rivalry or not, it is to be noted that there are few Jews in Mexico. Finally, the Americans build the railroads.

The Mexican proper is a retail trader, an employé, or, if rich, draws his revenues from haciendas, which in many cases he never sees, and where his money is made

for him. These are on an enormous scale. The chief part of the land is comprised in great estates, on which the peasants live in a semi-serfdom. Small farms are

scarcely known. For his fine hacienda in the state of

Oaxaca ex-President Diaz is said to have paid over a million of dollars; on another the appliances alone cost a

million. The revenues of Mexican proprietors have been heretofore devoted to the purchase of more real estate, or loaned out at interest; at any rate, "salted down" in some such way as to be of little avail in setting the wheels of industry in motion.

Before adopting, however, the conventional view that this state of things is due to inferiority of race or enervating climate, considerations on the other side are to be looked at. In the first place is the revolutionary condition of the country, which until a recent date subjected the citizen who ventured to place his property beyond his immediate recall to a thousand embarrassments from one or another of the contending parties. Such immunities and advantages as there were, were enjoyed by foreigners alone, under the protection of their diplomatic representatives.

Again, there have been peculiar inequalities of fortune, coming down from the old Spanish monarchical times. There has been at one extreme of society a class too abject, and at the other, one in too leisurely circumstances, to greatly aspire to farther improvement, and the middle class has been of slow formation. The difficulties in the way of travel and communication with foreign parts for the middle class, from the bosom of which financial success chiefly springs, have been of a repressive sort.

The climate, of the central table-land at least, must not be considered enervating. One must lay his ideas of climate, as depending upon latitude, aside, and comprehend that here it is a matter of elevation above the sea. Individual Mexicans are to be met with who, under the stimulus of the new feeling of security, have embarked their capital, put plenty of irons in the fire, and appear to handle them with skill. The street railways of the capital, an extensive and excellent system, are under native management exclusively. It is as successful in mining. It was only when the great Real del Monte Company at Pachuca, formerly English, passed into Mexican hands that its mines became profitable.

I should be strongly of the opinion that the backwardness of the Mexican is not the result of a native incapacity or lack of appetite for gain, but chiefly of the physical conformation of the country. The mule-path is traced like a vast hieroglyphic over the face of it, and in this is read the secret—lack of transportation.

But the zealous advocate of race and "Northern energy" objects: "How long is it since we had no railroads ourselves? And yet did we not reach a very pretty degree of civilization without them?"

But Mexico not only had no railways, but not even rivers nor ports. It was waterways which made the prosperity of nations before the day of steam. It is hardly credible, the completeness of the deprivations to which, this interesting country has been so long subjected. The wonder is, to any experienced in the diligence travel, and the dreary slowness of the journeys, at a foot-pace, by beasts of burden, not that so little, but so very much, has been done. On the trail to the coast at Acapulco, for instance —in popular phrase a mere camino de pájaros (road for birds)— have grown up some charming towns, like Iguala, the scene of the Emperor Iturbide's famous Plan, which, it seems to me, the Anglo-Saxon race would hardly ever have originated under such circumstances.

Commerce and trade in such a land naturally have their peculiar aspects. There is, in the first place, the

complicated tariff, already referred to. Americans should not let a new-born enthusiasm for a promising market hurry

MODERN SHOP-FRONTS AT MEXICO.

them into consignments without a thorough understanding of the premises. As to engaging in undertakings in the country itself, one who had done so held that the new-comer should make his residence there for six months or a year, and first acquaint himself with the people, their customs, and language.

"Better make it two years, on the whole," he said, reflectively, "and then he will go home again and let it alone altogether."

Without sharing this saturnine view, the importance of some preliminary acquaintance cannot be too strongly insisted upon. The great inertia of customs and ways of looking at things so different from our own is appreciated more and more as time goes on.

The most promising openings at present would seem to be, for capital, to work up into manufactures the raw material with which the country abounds. These opportunities will increase with the growth of transportation. Labor is cheap. The peons have little inventive but sufficient imitative talent, and make excellent mill-hands. They work for twenty-five and thirty-seven cents a day, and have no trades-unions nor strikes. There is little opening as yet for persons of small means. The government has taken but its first rudimentary steps toward the encouragement of immigration, and the path is beset with difficulties.

A commercial treaty is now in the hands of the Senate of the United States. It will be adopted in some form before long, and may result in the improvement of local business opportunities, as it must in the volume of trade, between the two countries. What we want is such a reduction of duties as to put us on the same footing at least as England (in favor of which there is a certain discrimination), so that our goods and machinery can be sold in the country on reasonable terms. It is predicted that a trade which is now about $30,000,000 per annum (including both exports and imports) can be made $100,000,000. The Mexicans, on their side, desire admission for their sugar and hemp. The treaty has met with its chief opposition thus far from our Southern sugar-planters. Their fear of competition is hardly reasonable at present. Our own product seems more likely to go to Mexico at first. It is a matter of note that sugar has been selling at eighteen cents a pound of late at old Monterey, in the country which professes to raise it.* The total

.* Detailed figures of our trade with Mexico, and other useful matters, will be found in the "Border States of Mexico," by Leonid Hamilton. Chicago, 1882.

value of the exports from Mexico for the past fiscal year has been $29,000,000. Of these $14,000,000 came to us, and $10,000,000 went to England. Our own exports to Mexico for 1881 were somewhat over $11,000,000.

II.

At present Mexico is perhaps the most difficult country in which to do business in the civilized world. A customer four or five hundred miles off, even on the best roads, is five or six days' journey distant. In preparing for it it is not long since he was accustomed to first make his will. The merchant has friendly as well as commercial relations with his customer. He is more or less his banker at the same time, not for the resulting profit, but because it is expected of him. If he does not offer such

accommodation some other house will. Credits are long, and it is not expected that interest will be charged even on quite liberal overlaps of time.

Payment is made in the bulky silver currency of the country; and this is sent in large sums by guarded convoys, the conductas, which converge upon the capital four times a year—in January, April, August, and November. There were but two banks issuing bills at this time, and these to but a small amount, and receivable only at short distances from the capital. One of these was a private corporation, the other the National Monte de Piedad, or pawn-shop.

The visitor becomes early acquainted with the Mexican "dollar of the fathers," to his sorrow. Sixteen of them weigh a solid pound. It is obviously impossible to carry even a moderate quantity of this money concealed, or to carry it at all with comfort. The unavoidable exhibition

of it, held in laps, chinking in valises, standing in bags.

and poured out in prodigious streams at the banks and commercial houses, is one of the features of life.

Guadalajara, the supply from which unites with that from Zacatecas at Queretaro, is the northernmost point from which money is despatched by conducta to Mexico. A portion of that even from here is despatched to San Francisco, by the port of San Blas, just as a part of that from Zacatecas goes to Tampico through San Luis Potosi. The country north of San Luis to the east ships its funds to Matamoras; those of Durango are divided between Matamoras and Mazatlan; while Puebla, Oaxaca, and the rest of the south find their natural outlet at Vera Cruz.

THE "PORTALES" AT MEXICO.

The importance of the great conducta in these times is diminished by the growing safety of the transport of money

by private hands. Its days are numbered with the progress of the railways, nearing so rapidly the central cluster of cities in which it has its origin. Even now it no longer came wholly to town, but took the Central train at the first feasible point, at Huehuetoca, the Spanish cut for the drainage of the valley. Its place as a spectacle is

filled by the pay conductors of the railroads.

A revision of these accounts is needed almost from moment to moment as I write, to keep pace with the rapid changes in affairs. A National Bank and banks of foreign incorporators have been established in the mean time, with

authority to issue large amounts of but inefficiently secured paper. The Mexican National Bank may now issue bills to the amount of $60,000,000, upon a capital of

$20,000,000. They are legal tender from individuals to the government, but not from the government to individuals, nor between individuals. One of the arguments in favor of this bank, our minister was assured, was that it would counteract in some sort the influence of the United

States: the usual patriotic leaven cropping up, it will be seen; though how it should accomplish the purpose in view it is by no means easy to understand. A flood of depreciated paper is driving the solid coin out of circulation; so that, while the traveller may be now able to

carry his money comfortably about him, there may be much worse in store for the Mexicans themselves than the handling of bags of unwieldy dollars. It is not

pleasant to see also that the government shows some unusual pecuniary embarrassment. Its expenditures for

the last fiscal year exceeded its revenues by ten per cent., and a loan is talked of. Should a spirit of recklessness enter into the management of the finances, in all this whirl of novelties, complicated by the issues of paper, a crisis might be precipitated, which would, of course, have to be counted among the retarding influences on the railways.

III.

Shops and shopping in Mexico follow much more European than American traditions. A fanciful. title over the door of the shop takes the place of the name of a firm or single proprietor. You have no Smith & Brown, but, instead—on the sign of a dry-goods store, for instance—"The Surprise," or "The Spring-time," or "The Explosion." A jeweller's is apt to be called "The Pearl," or "The Emerald;" a shoe-store, "The Foot of Venus," or

"The Azure Boot."

The windows are tastefully draped, after the way of shop-windows. Within stand a large force of clerks, touching shoulder to shoulder. They seem democratic in their manners, even by an American standard. They shake hands over the counter with a patron with whom they have enjoyed a slight previous acquaintance; ask a mother of a family, perhaps, after the health of "Miss Lolita" and "Miss Soledad," her daughters, who may have accompanied her thither. One of them, they hear, is going to be married. Perhaps this is accounted for by the presence among the minor clerks of some of considerable social position—some of the class you meet with afterward at the select entertainments of the Minister of Guatemala, for instance. But a limited choice of occupations has been open to the youth of Mexico, and those who cared to work have had to take such places as they could. They apply now with great eagerness for the positions of every sort offering under the new enterprises.

It was not etiquette of late for ladies of the upper class to do shopping in public, except from their carriages, the goods being brought out to them at the curb-stone. Now they may enter shops. A considerable part of the buying, as of furniture and other household goods, is still done by the men of the family. Nor was it etiquette for ladies to be seen walking in the streets, even with a maid, except to and from mass in the morning.

The change in both respects is ascribed to the horsecars. The point of ceremony, it appears, was founded somewhat upon the difficulty of getting about.

Americanism now appears in the streets with increasing frequency, in the signs of dealers in arms, sewing-machines, and other of our useful inventions. Our insurance companies, too, are a novel idea, to which the Mexicans seem to take with much readiness. The principal shopping hours are from four to six o'clock of the afternoon. From one till three, or even four, little is done. Even the horse-cars do not run in the middle of the day. There is a general stoppage of affairs for dinner. It is but a short time since that enterprising person, the commercial traveller, was unknown in the country, but now he begins to flourish here as elsewhere.

The profits of favorably situated houses, in the absence of keen competition, have been very large, and methods of doing business correspondingly loose. The Mexican merchant does not go into a fine calculation of the proportionate value of each item of a foreign invoice, but "lumps" the profit he thinks he ought to receive on the whole. Some articles, in consequence, can be bought at less than their real value, while others, in compensation, are exorbitantly advanced.

It is the smaller trade, and that most removed from metropolitan influences, which is the gayest and most entertaining as a spectacle. How many picturesque

market scenes does not one linger in! Each community has its own market-day, not to interfere with others. The flags of the plaza and market-houses, which are commodious and well built, are hidden under fruits, grains, cocoa sacks and mats, striped blankets and rebosos, sprawling brown limbs, embroidered bodices and kirtles, as if spread

with a thick, richly colored rug. A grade above the open market is the Parian, a bazaar of small shops, in which

goods, sales-people, and customers alike might all be put upon canvas only with the most vivid of hues.

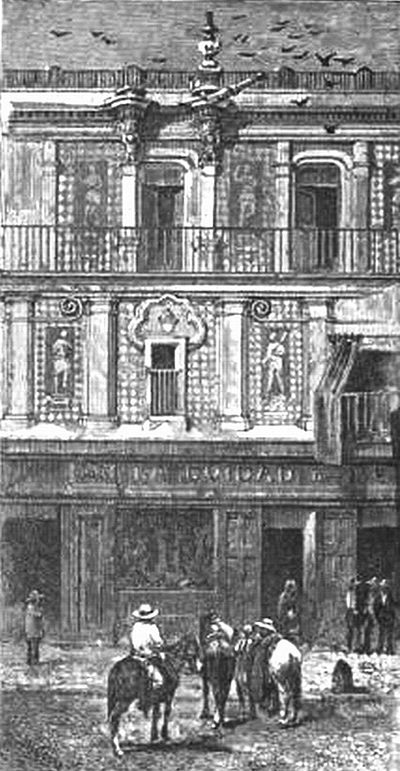

A "MERCERIA" AT PUEBLA.

I give some examples of the street architecture of the more important shops. The approach to many is under the welcome portales, shady in sunshine and dry in the wet. Not a few of the shops have been old Spanish palaces before being adapted to their present use. I transferred to my sketch-book a bit from the leading merceria (dry-goods store) of the important minor city of Puebla which I thought particularly interesting.

It was called, after the prevailing fashion, "The City of Mexico." The entire front upon which still remained the carved escutcheon, showing that it had been the residence of a family of rank—was faced up between carvings, in a gay pattern in tiles, the figures glazed, the rest an unglazed ground of red.