Natural History, Birds/Fissirostres

ORDER II. PASSERES.

(Perching Birds.)

Though for the most part the birds of this Order are of smaller size than those of the others, yet the immense number of species included in it, which is about equal to that of all others together, renders it the most important of all. It is also considered by naturalists as the most typical; that is, as displaying the properties which distinguish a bird from other animals, developed in the greatest perfection. Great varieties of form and structure are found in a group so immense as this; so that but few positive characters can be assigned which are at the same time common to the whole, and peculiar to them. The power of grasping the branches and twigs of trees with the feet, and the habit of perching upon these, are prominent in the Order; the hind toe is always present, and the claws are not capable of being elevated, as in the birds of prey. The greater number of the species habitually dwell in woods and thickets. The power of flight exists throughout the Order in full perfection, and in some of its genera, as the Swifts and the Humming-birds, may be considered as at its greatest development. The beak varies greatly in form, but its general shape is that of a cone, more or less lengthened. In some of the genera which retain predaceous propensities, a trace of the tooth which marks the upper mandible of the Falcon, remains in a notch near the tip; a mark which is obliterated by imperceptible gradations. The food of the Passerine birds embraces a wide variety of substances, but yet the vast majority feed either upon insects or upon vegetable seeds; and in almost every instance these are procured by the beak alone, without the aid of the feet.

To this Order, with scarcely a single exception, belong the birds whose voices are uttered in notes of melody. Every one is acquainted with the song of a bird; and there are, probably, few whose hearts are not in some degree open to the sweet and soothing influence of its associations. To walk out on a sunny morning in early spring, and listen to the lark as he soars up invisibly into the bright sky, or to the broken whistle, so rich and mellow, of the blackbird, among the yet bare and leafless twigs of the grove; or, by and bye, when the forest has put on its verdure, to walk through its leafy bowers, when thousands of throats are pouring forth their sweet warblings around,—this is indeed delightful.

"'Tis pleasant, 'tis pleasant in greenwood-shade,

When the merle and the mavis are singing."

The song of birds seems to be connected with the passion of love. In a wild state birds do not in general sing, except during the pairing season, when the trilling forth of their wild melodies appears to be designed to please and cheer their mates. Some naturalists think that the particular notes which constitute the distinctive melody, in any given species, are the result of imitation alone, being handed down by what we may call tradition; and that if a young bird were brought up without ever having heard the song of its species, it would be destitute of it.

It is in this Order, also, that we find the instinct of nest-building most perfectly displayed. The specimens of nests which are prepared, we can hardly say built, by other birds, are rude structures, consisting mostly of loose aggregations of rough materials with scarcely an attempt at construction. But very many of the Passerine birds build most elaborate and elegant structures, of which we may mention as instances, the compact felted nests of the Humming-bird, of the Gold-finch, and of the Bottle-tit, and the woven purses of the Orioles and the Starlings.

The study of this immense assemblage of species is facilitated by its sub-division into four Tribes, characterized by the varying form of the beak, and named respectively Fissirostres, Tenuirostres, Dentirostres, and Conirostres.

TRIBE I. FISSIROSTRES.

The beak in this Tribe is short, but broad, and more or less flattened horizontally, often hooked at the tip, with the mouth very deeply cleft: the upper mandible is not notched. The feet are small and feeble. Most of the species feed on insects, which they capture on the wing, but one genus subsists on fishes.

The tropical regions are the principal home of the fissirostral birds; such species as reach to the temperate zone, are, for the most part, migratory visitors, retiring on the approach of winter to more genial climes. Many of the species are distinguished for the brilliant hues which adorn their plumage.

HEAD OF NYCTIBIUS JAMAICENSIS.

The six Families of the Fissirostres are Caprimulgidæ, Hirundinidæ, Todidæ, Trogonidæ, Alcedinidæ, and Meropidæ.

Family I. Caprimulgidæ.

(Nightjars.)

The analogy between these birds and the Owls has been observed not only by naturalists, but even by the vulgar, as the common names of our native species, Fern Owl, Churn Owl, &c., indicate. Indeed, the nocturnal flight, the feathered feet, the large ears and eyes, as also the sort of disk that surrounds the face, and the saw-like edge of the first wing-quill, observable in some species, the downiness of the plumage, its sombre but varied hues, and their exquisitely mottled and pencilled arrangement, all form so many characters, which evidently point to the Nightjars as the connecting link between the Accipitrine and the Passerine Orders,

The Caprimulgidæ have the beak exceedingly small, but the gape enormous; its sides are for the most part furnished with long and stiff bristles, which point forwards, and the interior of the mouth is moistened with a glutinous secretion. All these provisions aid the capture of large insects in flight, which form the principal prey of these birds. The wings are long, and formed for powerful flight; the feet are very small, plumed to the toes, which are connected at the base by a membrane; even the hind toe, which is directed inwards, is thus joined to the inner toe. The claw of the middle toe, in most of the genera, is dilated on one side, and its edge is cut into regularly formed teeth, like those of a comb.

The voices of the Nightjars, like those of the Owls, are often harsh and uncouth; but their utterance frequently possesses a vibratory or quivering character that is peculiar. "With a single exception, they are nocturnal in their activity. Their eggs are laid on the ground, with but a slight mat of loose materials in place of a nest. The species are widely spread; and some of those which inhabit tropical countries have remarkable appendages to some of their feathers. Their colours are usually various shades of black, brown, grey, and white, mingled in the most beautiful manner, with minute waves, lines, and spots.

Genus Caprimulgus. (Linn.)

The beak is here very minute and weak, the edges bent inwards, the mandibles not always meeting when closed. They are furnished with long bristles. The tarsi are short, but still distinct. All the toes are directed forwards; the inner and outer toes are equal; the middle claw is pectinate or comb-like. The foot is not formed for grasping; hence the birds sit lengthwise on a branch, not across it.

Our own beautiful Nightjar (Caprimulgus Europæus, Linn.) is migratory, arriving on the south-eastern coasts of this island about the middle of May, and departing about the end of September. As soon as it arrives, the swarms of cockchafers become its nightly prey, and when their season is ended, the fern-chafer affords it a plentiful fare. Moths also, and other night-flying insects, are pursued by it, particularly around the summits of trees, and are readily engulfed in its cavernous mouth, surrounded by divergent bristles. It has been supposed, at least sometimes, to take its flying prey with its little foot, and deliver it to its mouth; and the securing of the insect in this manner has been thought one object of the serrated claw.

It frequently sits on a branch or a fence-rail, and, with the head held as low as the feet, utters, with swollen, quivering throat, its singular jarring note, for a long space at a time, without seeming to draw breath. "As this song," says Mr. Jesse, "is a summer incident, the naturalist hears the first return of it with complacency; not from its melody, for it has none; but from

NIGHTJAR.

the pleasing association of summer ideas to which it gives rise." "Instead of being noxious and mischievous," continues this pleasing writer, "they are the most harmless and useful of birds, destroying the great enemies of vegetation, the scarabæi and phalænæ, which, though individually feeble, yet are of mighty efficacy in their infinite numbers, inflicting wide devastations on the grass and corn, and stripping whole groves, woods, and extensive forests of their foliage at once, so as to make them look as naked as in winter." "Their wings and tails are very long, by means of which they excel in sudden evolutions; and they can mount instantaneously from a level flight, like a sky-rocket. . . When flushed in sunshine, they drop again at once, so as to be in danger of being caught by spaniels, and look round them with astonishment; hence a notion prevails that they are foolish birds."[1]

Like many other birds, the female Nightjar, if suddenly surprised by an intruder, when she has young, will feign helpless lameness, tumbling along in an odd manner, to lure away the stranger from the centre of her anxious cares, by the hope of capturing her.

Family II. Hirundinidæ.

(Swallows.)

In the smallness of the beak, and the great width of the gape, the Swallows resemble the Nightjars, as they do also in the weakness and minuteness of their feet. They are birds, however, of far more powerful wing, and though they too pursue insects, which are captured and devoured during flight, yet as their season of activity is wholly confined to daylight, their plumage has neither the lax softness, nor the mottled style of coloration common to nocturnal birds. On the contrary, the plumage of the Swallows is always close and smooth, and very often burnished with a metallic gloss; while its prevailing colours are black (more or less changing into blue or green) above, and white (often varied with dull red) beneath.

The organs of flight are developed in a very high degree. Almost the whole life of these birds is passed in the air; from earliest "morn to dewy eve," we see them careering along in their rushing flight, and, as has been truly observed, they "dash along apparently as untired when evening closes, as when they began their aerial evolutions with the first dawn of day." They even drink on the wing;—sipping the pool or stream as they skim lightly over its surface. The feet, therefore, being little called into action, are small and weak; yet, as these birds frequently cling from rocks and walls, when they do rest, their toes are furnished with sharp and crooked claws, and the hind-toe can, either wholly, as in the Swifts, or partially, as in the common Chimney Swallow, be brought to point forward.

The Swallows, though widely dispersed over the globe, are eminently children of the sun: they extend, it is true, over the temperate zone, and even reach the Arctic Circle, but it is only in the summer season; on the approach of cold weather, they retire to the torrid climes of equatorial regions. The Swift, which is the most impatient of cold of our visitors, does not appear in England until May, and hastens to depart before the end of August. In almost all the European languages the connection of these birds with a bright and fervid sun, is embodied in the well-known proverb,

"One Swallow does not make a summer."

Genus Hirundo. (Linn.)

The Swallows and Martins are distinguished from the Swifts by the following characters:—the toes are directed, as in most Passerine birds, three forward and one backward; the feet are slender and comparatively weak, as are also the claws; the tail consists of twelve feathers, and is for the most part forked, often to a great extent; the wings have the first quill-feather the longest.

The Chimney Swallow (Hirundo rustica, Linn.) with its burnished upper plumage of steel-blue, its forehead and throat of chestnut-red, and its long forked tail, is well known; and its headlong flights and rapid evolutions as it plays over the stream or rushes through the streets of the town, are hailed as the attendants of summer. Who does not know the pleasant associations of the announcement, "The Swallows are come!" "The Swallow," says Sir Humphrey Davy, "is one of my favourite birds, and a rival of the Nightingale; for he glads my sense of seeing as much as the other does my sense of hearing. He is the joyous prophet of the year, the harbinger of the best season; he lives a life of enjoyment among the loveliest forms of nature; winter is unknown to him, and he leaves the green meadows of England in autumn for the myrtle and orange groves of Italy, and for the plains of Africa."

In the "Natural History of Selborne," the economy of this, as well as of our other species of Hirundinidæ, is detailed in an interesting manner. The Chimney Swallow usually arrives in this country about the 13th of April, and withdraws about the beginning of October, though stragglers often appear before, and linger after these periods. It builds with us, for the most part,

CHIMNEY SWALLOW.

in chimneys, but occasionally also it attaches its clay-built structure to the rafters of barns and outhouses, or within the shaft of an old well, or of an unworked coal-pit. "Five or six feet down the chimney does this little bird begin to form her nest, about the middle of May, which consists, like that of the House Martin, of a crust or shell composed of dirt or mud mixed with short pieces of straw to render it tough and permanent; with this difference, that whereas the shell of the Martin is nearly hemispheric, that of the Swallow is open at the top, and like half a deep dish: this nest is lined with fine grasses and feathers, which are aften collected as they float in the air.

"Wonderful is the address which this adroit bird shews all day long, in ascending and descending with security through so narrow a pass. . . . The progressive method by which the young are introduced into life is very amusing: first, they emerge from the shaft with difficulty enough, and often fall down into the rooms below: for a day or so they are fed on the chimney-top, and then are conducted to the dead leafless bough of some tree, where, sitting in a row, they are attended with great assiduity, and may then be called perchers. In a day or two more they become fliers, but are still unable to take their own food; therefore they play about near the place where the dams are hawking for flies; and when a mouthful is collected, at a certain signal given, the dam and the nestling advance, rising towards each other, and meeting at an angle; the young one all the while uttering such a little quick note of gratitude and complacency that a person must have paid very little regard to the wonders of nature, that has not often remarked this feat."[2]

Family III. Todidæ.

(Todies.)

The Todies constitute a small Family almost confined to the tropics, but found in both hemispheres. They are marked by having the beak broad, and very much flattened, usually blunt or rounded at the tip. The gape is wide, extending beneath the eyes, and is beset with bristles. In one Indian genus (Eurylaimus) the breadth of the beak at the base is nearly as great as the length. The feet are for the most part small and weak: the outmost toe is united to that which is next to it as far as to the terminal joint. The wings are short and rounded, and consequently the flight is feeble, and incapable of protraction.

Insects form the chief nutriment of the Todies, mingled, however, in some of the species, with berries.

Genus Todus. (Linn.)

The little birds to which this name is generically restricted, are confined to the islands of the West Indies and the tropical parts of the American continent. The species are few in number, and are characterized by a lengthened, flattened beak of nearly equal breadth throughout, but rounded at the point. The bristles of the gape are few. The wings are very short and rounded, and the feet weak.

The Green Tody (Todus viridis, Linn.) is one of the most common, and one of the most beautiful birds of the greater West Indian isles. Its upper plumage is of bright green,—brilliant as an emerald,—its throat rich velvety crimson, and its under parts pale yellow, with rosy sides.

It sits on a twig at the edge of the forest, or on some low bush by the side of the road, watching for passing insects: and so intent is it on its occupation, and so little terrified by the approach of man, that it will allow a person to stand within a few feet of it without moving; and it is not uncommon for the negro boys to creep up behind one and actually to clap their hands over the

GREEN TODY.

unsuspicious bird as it sits. But this abstraction is more apparent than real: if we watch it, we shall see that the odd-looking grey eyes are glancing hither and thither, and that ever and anon, the bird sallies out upon a short feeble flight, snaps at something in the air, and returns to his twig to swallow it. It is instructive to note by how various means the wisdom of God has ordained a given end to be attained. The Swallow and the Tody live on the same prey, insects on the wing, and the short, hollow, and feeble wings of the latter are as effectual to him as the long and powerful pinions are to the Swallow. He has no powers to employ in pursuing insects, but he waits till they come within his circumscribed range, and no less certainly secures his meal.

The Tody forms burrows, with the aid of both beak and claws, in earthy banks and the sides of ditches and ravines. At the bottom of its hole, which runs in a winding direction to the extent of a foot or more, and terminates in a sufficiently wide chamber, it collects fibres of roots, dry grass, moss, and cotton, and lays four or five eggs. The young do not emerge from the hole until they are fledged.

Family IV. Trogonidæ.

(Trogons.)

This is a small and compact group of birds of considerable size, remarkable for the brilliancy and beauty of their plumage. The colour of the upper parts is for the most part green, which reflects the splendour of burnished metal, while that of the under parts is frequently of the richest hues, blood-red, scarlet, rose-pink, orange, or yellow; set off, especially on the broad and lengthened tail, with variations of black and white, in the most delicate and elaborate pencillings.

The Trogons have the toes set as in the climbing birds, two before and two behind, yet they have not the habit or power of climbing; the feet are short and feeble. The wings also are short, but pointed; the quill-feathers are rigid, but the general plumage is very soft and plumose. The beak is short, somewhat conical, robust; the tip and generally the edges are notched or toothed; the gape is wide. The general form is full and plump, to which the dense and soft character of the plumage contributes; the head is rather large; the tail is long and ample; the feathers are graduated, regularly decreasing in length outward, and in one genus (Calurus) the tail-coverts are enormously developed, so as to conceal the tail, and depend in narrow flowing plumes of great length.

The food of the Trogons consists principally of insects. "They seize," observes Mr. Gould, in his splendid Monograph of this Family, "the flitting insect on the wing, which their wide gape enables them to do with facility; while their feeble tarsi and feet are such as to qualify them merely for resting on the branches as a post of observation whence to mark their prey as it passes, and to which, having given chase, to return. . . . Denizens of the intertropical regions of the Old and New World, they shroud their glories in the deep and gloomy recesses of the forest, avoiding the light of day and the observation of man; dazzled by the brightness of the meridional sun, morning and evening twilight is the season of their activity."

Genus Trogon. (Linn.)

The Trogons proper, which are confined to the hottest regions of South America, are distinguished by having the cutting edges of the beak both above and below, cut into notches : the fore toes are united as far as the first joint; the tarsus is feathered to the toes; the nostrils are concealed by bristles.

Shy and recluse in their habits, the Trogons are among the few birds that delight in the lone and sombre recesses of the forest. Even here they prefer to sit in the centre of a tree where the foliage is densest, rarely descending to the ground, or even to the lower branches. Azara, speaking of one species (and they seem to be much alike in their manners), observes, that it sits for a long time motionless, watching for insects that may pass within its reach, and which it seizes with adroitness; it is not gregarious, but dwells either in solitude or in pairs: its flight, which is rapid, and performed in vertical undulations, is not prolonged. These birds are so tame as to admit of a near approach; and they are even sometimes killed with a stick. They do not migrate, and are never heard, except in the breeding season; their note then consists of the frequent repetition of the syllables pee-o, in a strong, sonorous, and melancholy voice; the male and female answer each other. They form their nest on the trees, by digging into the lower part of the nest of a species of ant or termes, until they have made a cavity sufficiently large, in which the female deposits her eggs, of a white colour, and two, or as some assert, four in number. Azara has seen the male clinging to a tree after the manner of woodpeckers, occupied in digging a nest with his beak, while the female remained tranquil on a neighbouring tree.

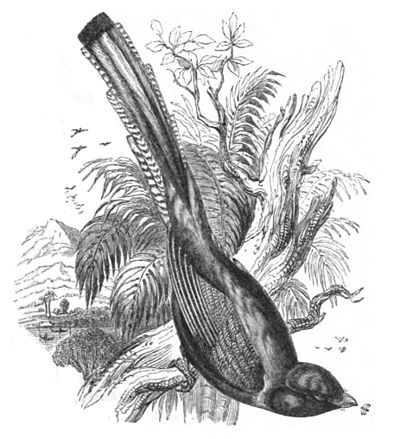

GRACEFUL TROGON.

We select for illustration the Graceful Trogon, (Trogon elegans, Gould,) of which the upper parts and breast are golden-green, and the lower parts rich scarlet; a white crescent crosses the chest; the outer tail-feathers are white, minutely barred with black; the secondaries and all the coverts of the wings are grey, delicately pencilled with black; the forehead and throat are black, and the beak light yellow. This beautiful bird is a native of Mexico.

Family V. Alcedinidæ.

(Kingfishers.)

While in the brilliant little Kingfisher of our own streams we trace a very manifest resemblance to the Todies, we find in the construction of its beak, and especially in its increased power, an indication of very different habits. The King-fishers are the most predatory of the Fissirostral tribe; our native species is a voracious devourer of fishes, and while most of the Family have similar instincts and appetites, there are not wanting species in which the beak is greatly enlarged, whose rapacity is formidable, even to reptiles, birds, and small quadrupeds.

The Family before us is characterized by a long, stout, pointed beak, with angular sides; small and feeble feet, the outmost and middle toes united to the last joint; wings rounded and hollow, incapable of protracted flight; a robust form, with a large head, and usually a short tail. Their plumage is dense and close, and commonly of blue or green hues. They are scattered over the world, but Australia with the adjacent isles, and South America, contain the greatest number of species.

Genus Alcedo. (Linn.)

The beak in this genus is very straight, sharp, compressed through its whole length, with the gape ample; the upper mandible is not at all bent at the point. The wings are somewhat rounded, the third quill being the longest. The tail is very short, scarcely reaching beyond its coverts. The feet are very weak; the outer and middle toes united; the inner and back toes very short.

The true Kingfishers, as their name implies, are aquatic in their habits, resorting to the banks of rivers, or to the sea-shore, where they watch for the rise of small fishes to the surface. On these they dart with the rapidity of a stone flung into the water, and rarely fail to emerge with the prey secured in the strong and sharp beak. They breed in holes in cliffs, which they themselves excavate; though sometimes they are said to appropriate a hole already formed. The plumage is blue or green, often varied on the under parts with red or chestnut.

The common Kingfisher (Alcedo ispida, Linn.) is well known, particularly in the southern part of our island, wherever there is a secluded and shaded stream. It is, as Sir William Jardine observes, "one of our most gaily tinted birds, and when darting down some wooded stream, and shone upon at times by the sunbeams, it may give some faint idea of the brilliant plumage that sports in the forests of the tropics, and that flits from place to place like so many lights in their deeply shaded recesses." The plumage of the upper parts is resplendent with emerald green, becoming on the tail ultramarine blue, while the under parts are of a pale orange hue; the throat and neck are varied with white and blue.

KINGFISHER.

The ordinary food of our beautiful Kingfisher is certainly fish; the stickleback and the minnow, with the young of larger species, supply his need; but he is said also to eat slugs, worms, and leeches. The manner in which he procures his prey is graphically drawn in the following picture of his habits by Mr. Martin:—"Occasionally it hovers at a moderate elevation over the water, and then darts down with astonishing velocity and suddenness on some unwary fish, which, heedless of its foe, ventures near the surface, and which is seldom missed by the keen-eyed bird. The ordinary manner, however, in which the Kingfisher captures its finny prey, is by remaining quietly perched on some stump or branch overhanging the water, and then intently watching, with dogged perseverance, for the favourable moment in which to make its plunge: it marks the shoals of minnows gliding past, the trout lurking beneath the concealment of some stone, or in the shadow of the bank,—the roach and dace pursuing their course. At length, attracted by a floating insect, one rises to take the prize; at that instant, like a shot, down descends the glittering bird, the crystal water scarcely bubbling with its plunge; the next moment it re-appears, bearing its victim in its beak, with which it returns to its resting-place; without loosing its hold, it passes the fish between its mandibles, till it has fairly grasped it by the tail; then, by striking smartly its head three or four times against the branch, ends its struggles, reverses its position, and swallows it whole."[3]

The Kingfisher, as has been observed, either digs, or selects a hole in some bank, as the scene of its domestic economy. It is always formed in an upward direction, that the accumulating moisture may drain off at the mouth. At the end, which is about three feet from the entrance, quantities of fish-bones are found, ejected by the parent birds, but whether these are placed there with or without design, is as yet a disputed point among naturalists. The prevailing opinion seems to be that the castings are purposely accumulated to form a sort of nest. Six or seven eggs

are laid, and the young do not leave the hole till able to fly, after which they sit on a branch for a few days, and are fed by the parents.

The Kingfisher is partially migratory in this country; and, though some remain with us through the winter, they retire at that time from the rivers and pools, to the estuaries and creeks of the southern coast, where they can still obtain their prey.

Fabulous stories of great antiquity are current concerning this bird; and in country places, even in this country, it is still the object of silly superstitions, which are not worth refuting.

Family VI. Meropidæ.

(Bee-eaters.)

We trace, in the lengthened form of the beak in this Family, an approach to the succeeding Tribe of Passerine birds; while yet many of the species have this character modified so as to resemble more the Fissirostral type. The outer pair of toes are united as in the Todies and Kingfishers. The beak is long, slender, tapering, and slightly curved; the wings are long and pointed; the first quill, for the most part, being nearly or quite as long as any other.

The Bee-eaters are generally of a green colour, varied with blue. They associate in flocks, which in their rapid flight, their evolutions, and their long wings and tails, much resemble Swallows, They feed on large insects, which they capture and eat during flight; and are confined to the continents and islands of the eastern hemisphere.

Genus Merops. (Linn.)

The generic characters of Merops are the following:—the beak is long, compressed, slightly bent, slender, but broad at the base; the upper part keeled or ridged; the tip entire, sharp, and not hooked. The wings are long, pointed; the second quill the longest. The tail is lengthened. The feet are short, with strong curved claws.

Like the Swallows, which, in appearance, they so much resemble, the Bee-eaters take their insect-prey on the wing; and as this consists largely of bees and wasps, it is remarkable that they are not stung. They burrow in the banks of rivers, digging their nestling holes to a considerable depth.

The European Bee-eater (Merops apiaster, Linn.) is a common summer visitor to the countries that border the Mediterranean, and has in a few rare instances been observed in the British islands. A flock of about twenty was seen in Norfolk in the year 1794, out of which one was shot, and exhibited at a meeting of the Linnean Society. It is a beautiful bird; the upper plumage is of a rich orange-brown, passing into yellow; the throat is yellow, with a collar of black; the wings, tail, and under parts are glossy greenish blue, changing with the play of light.

The prey which the Bee-eater selects has been observed from early times; both the Greek and Roman writers on rural economy have noticed it among the animals whose depredations on the industrious tenants of the hive must be watched against. Its destruction has a double object; for its flesh is sufficiently esteemed to be sold in the markets both of Italy and Egypt,

BEE-EATER.

Belon, quoted by Ray, writes thus concerning the Merops. "Flying in the air it catches and preys upon bees, as Swallows do upon flies. It flies not singly, but in flocks; and, especially, by the side of those mountains where the true thyme grows. Its voice is heard afar off, almost like the whistling of a man. Its singular elegance invites the Candy (Candia) boys to hunt for it with Cieadæ, as they do also for those greater swallows called Swifts, after this manner:—bending a pin like a hook, and tying it by the head to the end of a thread, they thrust it through a Cicada (as boys bait a hook with a fly), holding the other end of the thread in their hand. The Cicada, so fastened, flies nevertheless in the air, which the Merops spying, flies after it with all her force, and catching it, swallows pin and all, wherewith she is caught."

- ↑ Gleanings in Nat. Hist. 295.

- ↑ Nat. Hist. Selb.; Letter xviii. 2nd series.

- ↑ Pict. Museum, i. 297.