Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697/Book II

BOOK II.

THE AGE OF THE GODS.

Part II.

Masa-ya-a-katsu-katsu-haya-hi ama no oshi-ho-mi-mi no Mikoto, the son of Ama-terasu no Oho-kami, took to wife Taku-hata[1]-chi-chi-hime, daughter of Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto. A child was born to them named Ama-tsu-hiko-hiko-ho-no-ninigi no Mikoto[2]. Therefore his august grandparent, Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto, treated him with special affection, and nurtured him with great regard. Eventually he desired to establish his august grandchild Ama-tsu-hiko-ho-ho-ninigi no Mikoto as the Lord of the Central Land of Reed-Plains. But in that Land there were numerous Deities which shone with a lustre like that of fireflies, and evil Deities which buzzed (II. 2.) like flies. There were also trees and herbs all of which could speak. Therefore Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto assembled all the eighty Gods, and inquired of them, saying:—"I desire to have the evil Gods of the Central Land of Reed-Plains expelled and subdued. Whom is it meet that we should send for this purpose? I pray you, all ye Gods, conceal not your opinion." They all said:—"Ama-no-ho-hi no Mikoto is the most heroic among the Gods. Ought not he to be tried?"

Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto thereupon complied with the general advice, and made Ama-no-ho-hi no Mikoto to go and subdue them. This Deity, however, curried favour with Oho-na-mochi no Mikoto, and three years passed without his making any report. Therefore his son Oho-se-ihi no Mikuma no ushi[3] (also called Take[4]-mikuma no ushi) was sent. (II. 3.) He, too, yielded compliance to his father, and never made any report. Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto therefore again summoned together all the Gods and inquired of them who should be sent. They all said:—"Ame-waka-hiko,[5] son of Ame no Kuni-dama.[6] He is a valorous person. Let him be tried." Hereupon Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto gave Ame-waka-hiko a heavenly deer-bow and heavenly feathered arrows, and so despatched him. This God also was disloyal, and as soon as he arrived took to wife Shita-teru-hime,[7] the daughter of Utsushi-kuni-dama[8] (also called Taka-hime or Waka-kuni-dama). Accordingly he remained, and said:—"I, too, wish to govern the Central Land of Reed-Plains." He never reported the result of his mission. At this time, Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto, wondering why he was so long in coming and making his report, sent the pheasant Na-naki[9] to observe. The pheasant flew down and perched on the top of a many-branched cassia-tree which grew before Ame-waka-hiko's gate. Now (II. 4.) Ama-no Sagu-me[10] saw this and told Ame-waka-hiko, saying:—"A strange bird has come and is perched on the top of the cassia-tree." Then Ame-waka-hiko took the heavenly deer-bow and the heavenly feathered arrows which had been given him by Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto, and shot the pheasant, so that it died. The arrow having passed through the pheasant's breast, came before where Taka-mi-musubi no Kami was sitting. Then Taka-mi-musubi no Kami seeing this arrow, said:—"This arrow I formerly gave to Ame-waka-hiko. It is stained with blood, it may be because he has been fighting with the Earthly Deities." Thereupon Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto took up the arrow and flung it back down (to earth). This arrow, when it fell, hit Ame-waka-hiko on the top of his breast. At this time Ame-waka-hiko was lying down after the feast of first-fruits, and when hit by the arrow died immediately. This was the origin of the general saying, "Fear a returning arrow."

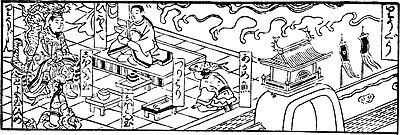

The sound of the weeping and mourning of Ame-waka-hiko's (II. 5.) wife Shita-teru-hime reached Heaven. At this time, Ame no Kuni-dama, hearing the voice of her crying, straightway knew that her husband, Ame-waka-hiko, was dead, and sent down a swift wind to bring the body up to Heaven. Forthwith a mortuary house was made, in which it was temporarily deposited. The river-geese were made the head-hanging bearers and broom-bearers.

One version is:—"The barn-door fowls were made head-hanging bearers, and the river-geese were made broom-bearers."

The sparrows were made pounding-women.

One version is:—"The river-geese were made head-hanging bearers and also broom-bearers, the kingfisher was made the representative of the deceased, the sparrows were made the pounding-women, and the wrens the mourners. Altogether (II. 6.) the assembled birds were entrusted with the matter."

For eight days and eight nights they wept and sang dirges.[11] Before this, when Ame-waka-hiko was in the Central Land of Reed-Plains, he was on terms of friendship with Aji-suki[12]-taka-hiko-ne no Kami. Therefore Aji-suki-taka-hiko-ne no Kami ascended to Heaven and offered condolence on his decease. Now this God was exactly like in appearance to Ame-waka-hiko when he was alive, and therefore Ame-waka-hiko's parents, relations, wife, and children all said:—"Our Lord is still alive," and clung to his garments and to his girdle, partly rejoiced and partly distracted. Then Aji-suki-taka-hiko-ne no Kami became flushed with anger and said:—"The way of friends is such that it is right that mutual condolence should be made. Therefore I have not been daunted by the pollution, but have come from afar to make mourning. Why then should I be mistaken for a dead person?" So he drew his sword, Oho-ha-kari,[13] which he had in his girdle? and cut down the mortuary house, which fell to earth and became a mountain. It is now in the province of Mino, by the upper waters of the River (II. 7.) Ayumi. This is the mountain of Moyama (mourning mountain). This is why people take care not to mistake a living for a dead person.

After this, Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto again assembled all the Gods that they might select some one to send to the Central Land of Reed-Plains. They all said:—"It will be well to send Futsu-nushi[14] no Kami, son of Iha-tsutsu no wo[15] and Iha-tsutsu no me, the children of Iha-saku-ne-saku[16] no Kami."

Now there were certain Gods dwelling in the Rock-cave of Heaven, viz. Mika no Haya-hi[17] no Kami, son of Idzu no wo-bashiri[18] no Kami, Hi no Haya-hi no Kami, son of Mika no Haya-hi no Kami, and Take-mika-dzuchi no Kami,[19] son of Hi no Haya-hi no Kami. The latter God came forward and said:—"Is Futsu-nushi no Kami alone to be reckoned a hero? And am I not a hero?" His words were animated by a spirit of indignation. He was therefore associated with Futsu-nushi no Kami and made to subdue the Central Land of Reed-Plains. The two Gods thereupon descended and arrived at the Little Shore[20] of Itasa, in the Land of Idzumo. Then they drew their ten-span swords, and stuck them upside down in the earth, and sitting on their points questioned Oho-na-mochi no Kami, saying:—"Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto wishes to send down his August Grandchild to preside over this country as its Lord. He has therefore sent us two Gods to clear out and pacify it. What is thy intention? Wilt thou stand aside or no?" Then Oho-na-mochi no Kami answered and said:—"I must ask my son before I reply to you." At this time his son Koto-shiro-nushi no Kami was absent on an excursion to Cape Miho in the Land of Idzumo, where he was amusing himself by angling for fish.

(II. 8.) Some say:—"He was amusing himself by catching birds."

He therefore took the many-handed boat of Kumano,

[Another name is the Heavenly Pigeon-boat.]

and placing on board of it his messenger, Inase-hagi,[21] he despatched him, and announced to Koto-shiro-nushi no Kami the declaration of Taka-mi-musubi no Kami. He also inquired what language he should use in answer. Now Koto-shiro-nushi no Kami spoke to the messenger, and said:—"The Heavenly Deity has now addressed us this inquiry.[22] My father ought respectfully to withdraw, nor will I make any opposition." So he made in the sea an eight-fold fence of green branches, and stepping on the bow of the boat, went off. The messenger returned and reported the result of his mission. Then Oho-na-mochi no Kami said to the two Gods, in accordance with the words of his son:—"My son, on whom I rely, has already departed. I, too, will depart. If I were to make resistance all the Gods of this Land would certainly resist also. But as I now respectfully withdraw, who else will be so bold as to refuse submission?" So he took the broad spear which he had used as a staff when he was pacifying the land and gave it to the two Gods, saying:—"By means of this spear I was at last (II. 9.) successful. If the Heavenly Grandchild will use this spear to rule the land, he will undoubtedly subdue it to tranquillity. I am now about to withdraw to the concealment of the short-of-a-hundred[23]-eighty road-windings."[24] Having said these words, he at length became concealed.[25] Thereupon the two Gods put to death all the rebellious spirits and Deities.

One version says:—"The two Gods at length put to death the malignant Deities and the tribes of herbs, trees and rocks. When all had been subdued, the only one who refused submission was the Star-God Kagase-wo.[26] Therefore they sent the Weaver-God Take-ha-dzuchi no Mikoto also, upon which he rendered submission. The two Gods therefore ascended to Heaven."

Ultimately they reported the result of their mission.

Then Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto took the coverlet which was on his true couch, and casting it over his August Grandchild, Amatsu-hiko-hiko-ho-ninigi no Mikoto, made him to descend. So the August Grandchild left his Heavenly Rock-seat, and with an awful[27] path-cleaving, clove his way through the eight-fold clouds of Heaven, and descended on the Peak of Takachiho of (II. 10.) So[28] in Hiuga.

After this the manner of the progress of the August Grandchild was as follows:—From the Floating Bridge of Heaven on the twin summits of Kushibi, he took his stand on a level part of the floating sand-bank. Then he traversed the desert land of Sojishi from the Hill of Hitawo in his search for a country, until he came to Cape Kasasa, in Ata-no-nagaya. A certain man of that land appeared and gave his name as Koto-katsu-kuni-katsu Nagasa.[29] The August Grandchild inquired of him, (II. 11.) saying:—"Is there a country, or not?" He answered, and said:—"There is here a country. I pray thee roam through it at thy pleasure." The August Grandchild therefore went there and took up his abode. Now there was a fair maid in that land whose name was Ka-ashi-tsu-hime.

The August Grandchild inquired of this fair maid, saying:—"Whose daughter art thou?" She answered and said:—"Thy handmaiden[31] is the child of a Heavenly Deity by his marriage with Oho-yama-tsu-mi Kami."[Also called Kami Ata-tsu-hime or Ko no hana no saku-ya-hime.[30]]

The August Grandchild accordingly favoured[32] her, whereupon in one night she became pregnant. But the August Grandchild was slow to believe this, and said:—"Heavenly Deity though I am, how could I cause any one to become pregnant in the space of one night? That which thou hast in thy bosom is assuredly not my child." Therefore Ka-ashi-tsu-hime was wroth. She prepared a doorless[33] muro[34] (called utsumuro), and entering, dwelt therein. Then she made a solemn declaration, saying:—"If that which is in my bosom is not the offspring of the Heavenly Grandchild, it will assuredly be destroyed by fire, but if it is really the offspring of the Heavenly Grandchild, fire cannot harm it." So she set fire to the muro. The child which was born from the extremity of the smoke which first arose was called Ho no Susori no Mikoto (he was the ancestor of the Hayato); next the child which was born when she drew back and remained away from the heat was called Hiko-ho-ho-demi no Mikoto; the child which was next born was called Ho no akari no Mikoto (he was the ancestor of the Wohari no Muraji)—in (II. 12.) all three children.[35]

A long time after, Ama-tsu-hiko hiko-ho-no-ninigi no Mikoto died, and was buried in the Misasagi[36] of Hiuga no ye in Tsukushi.

In one writing it is said:—"Ama-terasu no Oho-kami gave command unto Ame-waka-hiko, saying:—'The Central Land of Reed-Plains is a region which it is for my child to rule over. Considering, however, that there are there certain rebellious, violent and wicked Deities, do thou therefore go first and subdue it.' Accordingly she gave him the Heavenly deer-bow and the Heavenly true-deer-arrows, and so despatched him. Ame-waka-hiko, having received this command, went down and forthwith married many daughters of the Earthly Deities. Eight years passed, during which he made no report of his mission. Therefore Ama-terasu-no Oho-kami summoned Omohi-kane no Kami (the Thought-combiner) and inquired the reason why he did not come. Now the Thought-combining Deity reflected and informed her, saying:—'It will be well to send the pheasant to inquire into this.' Hereupon, in accordance with this God's device, the pheasant was caused to go and spy out (II. 13.) the reason. The pheasant flew down and perched on the top of a many-branched cassia-tree before Ame-waka-hiko's gate, where it uttered a cry, saying:—'Ama-waka-hiko! wherefore for the space of eight years hast thou still not made a report of thy mission?' Now a certain Earthly Goddess, named Ama-no-sagu-me, saw the pheasant, and said:—'A bird of evil cry is sitting on the top of this tree. It will be well to shoot it and kill it.' So Ame-waka-hiko took the Heavenly deer-bow and the Heavenly true deer-arrow given him by the Heavenly Deity and shot it, upon which the arrow went through the pheasant's breast, and finally reached the place where the Heavenly Deity was. Now the Heavenly Deity seeing the arrow, said:—'This arrow I formerly gave to Ame-waka-hiko. Why has it come here?' So she took the arrow, and pronouncing a curse over it, said:—'If it has been shot with evil intent, let mischief surely come upon Ama-waka-hiko; but if it has been shot with a tranquil heart, let no harm befall him.' So she flung it back. It fell down and struck Ame-waka-hiko on the top of the breast, so that he straightway died. This is the reason why people at the present day say, 'Fear a returning arrow.' Now Ame-waka-hiko's wife and children came down from Heaven and went away upwards taking with them the dead body. Then they made a mourning house in Heaven, in which they deposited it and lamented over it. Before this Ame-waka-hiko was on friendly terms with Aji-suki-taka-hiko-ne no Kami. Therefore Aji-suki-taka-hiko-ne no Kami ascended to Heaven and condoled with them on the mourning, lamenting greatly. Now this God had by nature an exact resemblance to Ame-waka-hiko in appearance. Therefore Ame-waka-hiko's wife and children, when they saw him, rejoiced, and said:—'Our Lord is still alive.' And they clung to his robe and to his girdle, and could not be thrust away. Now Aji-suki-taka-hiko ne no Kami became angry, and said:—'My friend is dead, therefore have I come to make condolence. Why then should I be mistaken for a dead man?' So he drew his ten-span sword and cut down the mourning house, which fell to earth and became (II. 14.) a mountain. This is Moyama (Mount Mourning) in the province of Mino. This is the reason why people dislike to be mistaken for a dead person.

Now the glory of Aji-suki-taka-hiko ne no Mikoto was so effulgent that it illuminated the space of two hills and two valleys, and those assembled for the mourning celebrated it in song, saying:—

[Another version is that Aji-suki-taka-hiko-ne no Kami's younger sister, Shita-teru-hime, wishing to make known to the company that it was Aji-suki-taka-hiko ne no Mikoto who illuminated the hills and valleys therefore made a song, saying:—]

Like the string of jewels

Worn on the neck

Of the Weaving-maiden,

That dwells in Heaven—

Oh! the lustre of the jewels

Flung across two valleys

From Aji-suki-taka-hiko-ne![37]Again they sang, saying:—

To the side-pool—

The side-pool

Of the rocky stream

Whose narrows are crossed

By the country wenches

Afar from Heaven,

Come hither, come hither!

(The women are fair)

And spread across thy net

In the side-pool

Of the rocky stream.[38]These two poems are in what is now called a Rustic[39] measure.

After this Ama-terasu no Oho-kami united Yorodzu-hata Toyo-aki-tsu-hime, the younger sister of Omohi-kane no Kami to Masa-ya-a-katsu-katsu-no-haya-hi no Ama no Oshi-ho-mimi (II. 15.) no Mikoto, and making her his consort, caused them to descend to the Central Land of Reed-Plains. At this time Katsu-no-haya-hi no Ama no Oshi-ho-mimi no Mikoto stood on the floating bridge of Heaven, and glancing downwards, said:—'Is that country tranquillized yet? No! it is a tumble-down land, hideous to look upon.' So he ascended, and reported why he had not gone down. Therefore, Ama-terasu no Oho-kami further sent Taka-mika-tsuchi no Kami and Futsu-nushi no Kami first to clear it. Now these two Gods went down and arrived at Idzumo, where they inquired of Oho-na-mochi no Mikoto, saying:—'Wilt thou deliver up this country to the Heavenly Deity or not?' He answered and said:—'My son, Koto-shiro-nushi is at Cape Mitsu for the sport of bird-shooting. I will ask him, and then give you an answer.' So he sent a messenger to make inquiry, who brought answer and said:—'How can we refuse to deliver up what is demanded by the Heavenly Deity?' Therefore Oho-na-mochi no Kami replied to the two Gods in the words of his son. The two Gods thereupon ascended to Heaven and reported the result of their mission, saying:—'All the Central Land of Reed-Plains is now completely tranquillized.' Now Ama-terasu no Oho-kami gave command, saying:—'If that be so, I will send down my child.' She was about to do so, when in the meantime, an August Grandchild was born, whose name was called Ama-tsu-hiko-hiko-ho-no-ninigi no Mikoto. Her son represented to her that he wished the August Grandchild to be sent down in his stead. Therefore Ama-terasu no Oho-kami gave to Ama-tsu-hiko-hiko-ho no ninigi no Mikoto the three treasures, viz. the curved jewel of Yasaka gem, the eight-hand mirror, and the sword Kusanagi, and joined to him (II. 16.) as his attendants Ame no Koyane no Mikoto, the first ancestor of the Naka-tomi, Futo-dama no Mikoto, the first ancestor of the Imbe, Ame no Uzume no Mikoto, the first ancestor of the Sarume,[40] Ishi-kori-dome no Mikoto, the first ancestor of the mirror-makers, and Tamaya no Mikoto, the first ancestor of the jewel-makers, in all Gods of five Be. Then she commanded her August Grandchild, saying:—'This Reed-plain-1500-autumns-fair-rice-ear Land is the region which my descendants shall be lords of. Do thou, my August Grandchild, proceed thither and govern it. Go! and may prosperity attend thy dynasty, and may it, like Heaven and Earth, endure for ever.' When he was about to descend, one, who had been sent in advance to clear the way, returned and said:—'There is one God who dwells at the eight-cross-roads of Heaven, the length of whose nose is seven hands, the length of whose back is more than seven fathoms. Moreover, a light shines from his mouth and from his posteriors. His eye-balls are like an eight-hand mirror and have a ruddy glow like the Aka-kagachi.' (II. 17.) Thereupon he sent one of his attendant Deities to go and make inquiry. Now among all the eighty myriads of Deities there was not one who could confront him and make inquiry. Therefore he specially commanded Ame no Uzume, saying:—'Thou art superior to others in the power of thy looks. Thou hadst better go and question him.' So Ame no Uzume forthwith bared her breasts and, pushing down the band of her garment below her navel, confronted him with a mocking laugh. Then the God of the cross-ways asked her, saying:—'Ame no Uzume! What meanest thou by this behaviour?' She answered and said:—'I venture to ask who art thou that dost thus remain in the road by which the child of Ama-terasu no Oho-kami is to make his progress?' The God of the cross-ways answered and said:—'I have heard that the child of Ama-terasu no Oho-kami is now about to descend, and therefore I have come respectfully to meet and attend upon him. My name is Saruta-hiko no Oho-kami.'[41] Then Ame no Uzume again inquired of him, saying:—'Wilt thou go before me, or shall I go before thee?' He answered and said:—"I will go before and be his harbinger.' Ame no Uzume asked again, saying:—"Whither wilt thou go and whither will the August Grandchild go?' He answered and said:—'The child of the Heavenly Deity will proceed to the peak of Kushifuru of Takachiho in Hiuga in the Land of Tsukushi, and I will (II. 18.) go to the upper waters of the River Isuzu at Sanada in Ise. He accordingly said:—'Thou art the person who didst discover me. Thou must therefore escort me and

complete thy task.' Ame no Uzume returned and reported these circumstances. Thereupon the August Grandchild, leaving the Heavenly rock-seat, and thrusting apart the eight-piled clouds of Heaven, clove his way with an awful way-cleaving, and descended from Heaven. Finally, as had been arranged, the August Grandchild arrived at the peak of Kushifuru of Takachiho in Hiuga, in the land of Tsukushi. And Saruta-hiko no Kami forthwith proceeded to the upper waters of the River Isuzu at Sanada in Ise. Ame no Uzume no Mikoto, in accordance with the request made by Saruta[42] hiko no Kami, attended upon him. Now the August Grandchild commanded Ame no Uzume no Mikoto, saying:—'Let the name of the Deity whom thou didst discover be made thy title.' Therefore he conferred on her the designation of Sarume no Kimi.[43] So this was the origin of the male and female Lords of Sarume being both styled Kimi."[44]

(II. 19.) In one writing it is said:—"The Heavenly Deity sent Futsu-nushi no Kami and Take-mika-tsuchi no Kami to tranquillize the Central Land of Reed-Plains. Now these two Gods said:—'In Heaven there is an Evil Deity called Ama-tsu-mika-hoshi, or Ame no Kagase-wo. We pray that this Deity may be executed before we go down to make clear the Central Land of Reed-Plains.' At this time Iwahi-nushi[45] no Kami received the designation of Iwahi no Ushi. This is the God which now dwells in the land of Katori in Adzuma.[46] After this the two Deities descended and arrived at the Little Shore of Itasa in Idzumo, and asked Oho-na-mochi no Kami, saying:—'Wilt thou deliver up this country to the Heavenly Deity, or no?' He answered and said:—'I suspected that ye two gods were coming to my place. Therefore I will not allow it.' Thereupon Futsu-nushi no Kami forthwith returned upwards, and made his report. Now Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto sent the two Gods back again, and commanded Oho-na-mochi no Mikoto, saying:—'Having now heard what thou hast said, I find that there is profound reason in thy words. Therefore again I issue my commands to thee more circumstantially, that is to say:—Let the public matters which thou hast charge of be conducted by my grandchild, and do thou rule divine affairs. Moreover, if thou wilt dwell in the palace of Ama no Hi-sumi,[47] I will now build it for thee. I will take a thousand fathom rope[48] of the (bark of the) paper mulberry, and tie it in 180 knots. As to the dimensions of the building of the palace,[49] its pillars shall be high and massy, and its planks broad and thick. I will (II. 20.) also cultivate thy rice-fields for thee, and, for thy provision when thou goest to take pleasure on the sea, I will make for thee a high bridge, a floating bridge, and also a Heavenly bird-boat. Moreover, on the Tranquil River of Heaven I will make a flying-bridge. I will also make for thee white shields[50] of 180 seams, and Ame no Ho-hi no Mikoto shall be the president of the festivals in thy honour.' Hereupon Oho-na-mochi no Kami answered and said:—'The instructions of the Heavenly Deity are so courteous that I may not presume to disobey his commands. Let the August Grandchild direct the public affairs of which I have charge. I will retire and direct secret matters.' So he introduced Kunado no Kami to the two Gods, saying:—'He will take my place and will yield respectful obedience. I will withdraw and depart from here.' He forthwith invested him with the pure Yasaka jewels, and then became concealed for ever.[51] Therefore Futsu-nushi no Kami appointed (II. 21.) Kunado no Kami[52] as guide, and went on a circuit of pacification. Any who were rebellious to his authority he put to death, while those who rendered obedience were rewarded. The chiefs of those who at this time rendered obedience were Oho-mono-nushi[53] no Kami and Koto-shiro-nushi no Kami. So they assembled the eighty myriads of Gods in the High Market-place of Heaven, and taking them up to Heaven with them, they declared their loyal behaviour. Then Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto commanded Oho-mono-nushi no Kami, saying:—'If thou dost take to wife one of the Deities of Earth, I shall still consider that thy heart is disaffected. I will therefore now give thee my daughter Mi-ho-tsu hime to be thy wife. Take with thee the eighty myriads of Deities to be the guards of my August Grandchild to all ages.' So she sent him down again. Thereupon Ta-oki-ho-ohi no Kami, ancestor of the Imbe of the Land of Kii, was appointed hatter,[54] Hiko-sachi no Kami was made shield-maker,[55] Ma-hitotsu no Kami[56] was made metal-worker, Ame no Hi-washi[57] no Kami was appointed tree-fibre maker, and Kushi-akaru-dama no Kami (II. 22.) jewel-maker.[58]

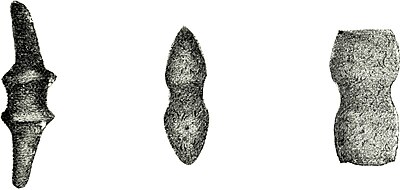

Taka-mi-musubi no Kami accordingly gave command, saying:—'I will set up a Heavenly divine fence[59] and a Heavenly rock-boundary wherein to practise religious abstinence[60] on behalf of my descendants. Do ye, Ame no Koyane no Mikoto and Futo-dama[61] no Mikoto, take with you the Heavenly divine fence, and go down to the Central Land of Reed-Plains. Moreover, ye will there practise abstinence[62] on behalf of my descendants.' So she attached the two Deities to Ame no Oshi-ho-mi-mi no Mikoto and sent them down. It was when Futo-dama no Mikoto was sent that the custom first began of worshipping this Deity with stout straps[63] flung over weak shoulders when taking the place of the Imperial hand. From this, too, the custom had its origin, by which Ame no Koyane no Mikoto had charge of divine matters. Therefore he was made to divine by means of the Greater Divination, and thus to do his service.[64]

(II. 23.) At this time Ama-terasu no Oho-kami took in her hand the precious mirror, and, giving it to Ame no Oshi-ho-mi-mi no Mikoto, uttered a prayer, saying:—'My Child, when thou lookest upon this mirror, let it be as if thou wert looking on me. Let it be with thee on thy couch and in thy hall, and let it be to thee a holy[65] mirror.' Moreover, she gave command to Ame no Ko-yane no Mikoto and to Futo-dama no Mikoto, saying:—'Attend to me, ye two Gods! Do ye also remain together in attendance and guard it well.' She further gave command, saying:—'I will give over to my child the rice-ears of the sacred garden,[66] of which I partake in the Plain of High Heaven.' And she straightway took the daughter of Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto, by name Yorodzu-hata-hime, and uniting her to Ame no Oshi-ho-mi-mi no Mikoto as his consort, sent her down. Therefore while she was still in the Void of Heaven,[67] she gave birth to a child, who was called Ama-tsu-hiko-ho no ninigi no Mikoto. She accordingly desired to send down this grandchild instead of his parents. Therefore on him she bestowed Ame no Ko-yane no Mikoto, Futo-dama no Mikoto, and the Deities of the various Be,[68] all without exception. She gave him, moreover, the things belonging to his person,[69] just as above stated.

After this, Ame no Oshi-ho-mi-mi no Mikoto went back again to Heaven. Therefore Ama-tsu-hiko-ho no ninigi no Mikoto descended to the peak of Takachiho of Kushibi in (II. 24.) Hiuga. Then he passed through the Land of Munasohi,[70] in Sojishi, by way of the Hill of Hitawo, in search of a country, and stood on a level part of the floating sand-bank. Thereupon he called to him Koto-katsu-kuni-katsu-Nagasa, the Lord of that country, and made inquiry of him. He answered and said:—'There is a country here. I will in any case obey thy commands.' Accordingly the August Grandchild erected a palace-hall and rested here. Walking afterwards by the sea-shore, he saw a beautiful woman. The August Grandchild inquired of her, saying:—'Whose child art thou?' She answered and said:—'Thy handmaiden is the child of Oho-yama-tsu-mi no Kami. My name is Kami-ataka-ashi-tsu-hime, and I am also called Ko-no-hana-saku-ya-hime.' Then she said:—'I have also an elder sister named Iha-naga-hime.'[71] The August Grandchild said:—'I wish to make thee my wife. How will this be?' She answered and said:—'I have a father, Oho-yama-tsu-mi no Kami, I pray thee ask him.' The August Grandchild accordingly spake to Oho-yama-tsu-mi no Kami, saying:—'I have seen thy daughter and wish to make her my wife.' Hereupon Oho-yama-tsu-mi no Kami sent his two daughters with one hundred tables of food and drink to offer them respectfully. Now the August Grandchild thought the elder sister ugly, and would not take her. So she went away. But the younger sister was a noted beauty. So he took her with him and favoured her, and in one night she became pregnant. Therefore Iha-naga-hime was greatly ashamed, and cursed him, saying:—'If the August Grandchild had taken me and not rejected me, the children born to him would have been long-lived, and would have endured for ever like the massy rocks. But seeing that he has not done so, but has married my younger sister only, the children born to him will surely be decadent like the flowers of the trees.'"

One version is:—"Iha-naga-hime, in her shame and resentment, spat and wept. She said:—'The race of visible mankind shall change swiftly like the flowers. of the trees, and shall decay and pass away.' This is the (II. 25.) reason why the life of man is so short.

After this, Kami-ataka-ashi-tsu-hime saw the August Grandchild, and said:—'Thy handmaiden has conceived a child by the August Grandchild. It is not meet that it should be born privately.' The August Grandchild said:—'Child of the Heavenly Deity though I am, how could I in one night cause anyone to be with child? Now it cannot be my child.' Kono-hana-saku-ya-hime was exceedingly ashamed and angry. She straightway made a doorless muro, and thereupon made a vow, saying:—'If the child which I have conceived is the child of another Deity, may it surely be unfortunate. But if it is truly the offspring of the Heavenly Grandchild, may it surely be alive and unhurt.' So she entered the muro, and burnt it with fire. At this time, when the flames first broke out, a child was born who was named Ho-no-susori no Mikoto; next when the flame reached its height, a child was born who was named Ho-no-akari no Mikoto. The next child which was born was called Hiko-ho-ho-demi no Mikoto,[72] and also Ho-no-wori no Mikoto."

In one writing it is said:—"When the flames first became bright, a child was born named Ho-no-akari no Mikoto; next, when the blaze was at its height, a child was born named Ho-no-susumi[73] no Mikoto, also called Ho-no-suseri no Mikoto; next, when she recoiled from the blaze, a child was born named Ho-no-ori-hiko-ho-ho-demi no Mikoto—three children in all. The fire failed to harm them, and the mother, too, was not injured in the least. Then with a bamboo knife she cut their navel-strings.[74] From the bamboo knife which she threw away, there eventually sprang tip a bamboo grove. Therefore that place was called Taka-ya.[75]

(II. 26.) Now Kami-ataka-ashi-tsu-hime by divination fixed upon a rice-field to which she gave the name Sanada, and from the rice grown there brewed Heavenly sweet sake, with which she entertained him. Moreover, with the rice from the Nunada rice-field she made boiled rice and entertained him therewith."[76]

In one writing it is said:—"Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto took the coverlet which was on the true couch and wrapped in it Ama-tsu-hiko-kuni-teru-hiko-ho no ninigi no Mikoto, who forthwith drew open the rock-door of Heaven, and thrusting asunder the eight-piled clouds of Heaven, descended. At this time Ama-no-oshi-hi no Mikoto, the ancestor of the Oho-tomo[77] no Muraji, taking with him Ame-kushi-tsu Oho-kume, the ancestor of the Kume Be,[78] placed on his back the rock-quiver of Heaven, drew on his forearm a dread loud-sounding elbow-pad,[79] and grasped in his hand a Heavenly vegetable-wax-tree bow and a Heavenly feathered arrow, to which he added an eight-eyed sounding-arrow.[80] Moreover he girt on his mallet-headed (II. 27.) sword,[81] and taking his place before the Heavenly Grandchild, proceeded downwards as far as the floating bridge of Heaven, which is on the two peaks of Kushibi of Takachiho in So in Hiuga. Then he stood on a level part of the floating sand-bank and passed through the desert land

of Sojishi by way of Hitawo in search of a country until he came to Cape Kasasa in Ata no Nagaya. Now at this place there was a God named Koto-katsu-kuni-katsu-Nagasa. Therefore the Heavenly Grandchild inquired of this God, saying:—'Is there a country?' He answered and said:—'There is.' Accordingly he said:—'I will yield it up to thee in obedience to thy commands.' Therefore the Heavenly Grandchild abode in that place. This Koto-katsu-kuni-katsu no Kami was the child of Izanagi no Mikoto, and his other name is Shiho-tsu-tsu-no oji."[82]

In one writing it is said:—"The Heavenly Grandchild favoured Ataka-ashi-tsu-hime, the daughter of Oho-yama-tsu-mi no Kami. In one night she became pregnant, and eventually gave birth to four children. Therefore Ataka-ashi-tsu-hime took the children in her arms, and, coming forward, said:—'Ought the children of the Heavenly Grandchild to be privately nurtured? Therefore do I announce to thee the fact for thy information.' At this time the Heavenly Grandchild looked upon the children, and, with a mocking laugh, said:—'Excellent—these princes of mine! Their birth is a delightful piece of news!' Therefore Ataka-ashi-tsu-hime was wroth, and said:—'Why dost thou mock thy handmaiden?' The Heavenly Grandchild said:—'There is surely some doubt of this, and therefore did I mock. How is it possible for me, Heavenly God though I am, in the space of one night to cause anyone to become pregnant? Truly they are not my children.' On this account Ataka-ashi-tsu-hime was more and more resentful. She made a doorless muro, into which she entered, and made a vow, saying:—'If the children which I have conceived are not the offspring of the Heavenly Grandchild, let them surely perish. But if they are the offspring of the Heavenly Grandchild, let them (II. 28.) suffer no hurt.' So she set fire to the muro and burnt it. When the fire first became bright, a child sprang forth and announced himself, saying:—'Here am I, the child of the Heavenly Deity, and my name is Ho-no-akari no Mikoto. Where is my father?' Next, the child who sprang forth when the fire was at its height also announced himself, saying:—'Here am I, the child of the Heavenly Deity, and my name is Ho-no-susumi no Mikoto. Where are my father and my elder brother?' Next, the child who sprang forth when the flames were becoming extinguished also announced himself, saying:—'Here am I, the child of the Heavenly Deity, and my name is Ho-no-ori no Mikoto. Where are my father and my elder brothers?' Next, when she recoiled from the heat, a child sprang forth, and also announced himself, saying:—'Here am I, the child of the Heavenly Deity, and my name is Hiko-ho-ho-demi no Mikoto. Where are my father and my elder brothers?' After that, their mother, Ataka-ashi-tsu-hime, came forth from amidst the embers, and approaching, told him, saying:—'The children which thy handmaiden has brought forth, and thy handmaiden herself, have of our own accord undergone the danger of fire,[83] and yet have suffered not the smallest hurt. Will the Heavenly Grandchild not look on them?' He answered and said:—'I knew from the first that they were my children, only, as they were conceived in one night, I thought that there might be suspicions, and I wished to let everybody know that they are my children, and also that a Heavenly Deity can cause pregnancy in one night. Moreover, I wished to make it evident that thou dost possess a wonderful and extraordinary dignity, and also that our children have surpassing spirit. Therefore it was that on a former day I used words of mockery.'"

In one writing it is said:—"Ame no Oshi-ho-ne no Mikoto took to wife Taku-hata-chichi-hime Yorodzu-hata[84] hime no Mikoto, daughter of Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto."

Another version says:—"Honoto-hata-hime-ko-chichi-hime no Mikoto, daughter of Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto." She bore to him a child named Ama-no-ho-no-akari no Mikoto. Next she bore Ama-tsu-hiko-ne-ho-no-ninigi-ne no Mikoto. The child of Ama-no-ho-no-akari no Mikoto was called Kayama no Mikoto. He is the ancestor of (II. 29.) the Ohari no Muraji.

When Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto was sending down the Heavenly Grandchild Ho-no-ninigi no Mikoto to the Central Land of Reed-Plains, she commanded the eighty myriads of Gods, saying:—"In the Central Land of Reed-Plains, the rocks, tree-stems and herbage have still the power of speech. At night, they make a clamour like that of flames of fire; in the day-time they swarm up like the flies in the fifth month, etc., etc." Now Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto gave command, saying:—"I formerly sent Ame-waka-hiko to the Central Land of Reed-Plains, but he has been long absent, and until now has not returned, perhaps being forcibly prevented by some of the Gods of the Land." She therefore sent the cock-pheasant Na-naki to go thither and spy out the reason. This pheasant went down, but when he saw the fields of millet and the fields of pulse he remained there, and did not come back. This was the origin of the modern saying, "The pheasant special messenger." Therefore she afterwards sent the hen-pheasant Na-naki, and this bird came down and was hit by an arrow shot by Ame-waka-hiko, after which she came up and made her report, etc., etc. At this time Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto took the coverlet which was upon the true couch, and having clothed therewith the Heavenly Grandchild Ama-tsu-hikone Ho-no-ninigi-ne no Mikoto, sent him downwards, thrusting asunder the eight-piled clouds of Heaven. Therefore this God was styled Ame-kuni-nigishi-hiko-ho-ninigi no Mikoto. Now the place at which he arrived on his descent is called the Peak of Sohori-yama of Takachiho (II. 30.) in So in Hiuga. When he proceeded therefore on his way, etc., etc.,[85] he arrived at Cape Kasasa in Ata, and finally ascended the Island of Takashima in Nagaya. He went round inspecting that land, and found there a man whose name was Koto-katsu-kuni-katsu Nagasa. The Heavenly Grandchild accordingly inquired of him, saying:—"Whose land is this?" He answered and said:—"This is the land where Nagasa dwells. I will, however, now offer it to the Heavenly Grandchild." The Heavenly Grandchild again inquired of him, saying:—"And the maidens who have built an eight-fathom palace on the highest crest of the waves and tend the loom with jingling wrist jewels, whose daughters are they?" He answered and said:—"They are the daughters of Oho-yama-tsu-mi no Kami. The elder is named Iha-naga-hime, and the younger is named Kono-hana saku-ya-hime, also called Toyo-ata-tsu hime, etc., etc." The August Grandchild accordingly favoured Toyo-ata-tsu hime, and after one night she became pregnant. The August Grandchild doubting this, etc., etc. Eventually she gave birth to Ho-no-suseri no Mikoto; next she bore Ho-no-ori no Mikoto, also called Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto. Proof having been given by the mother's vow, it was known exactly that they were truly the offspring of the Heavenly Grandchild. Toyo-ata-tsu hime however was incensed at the Heavenly Grandchild, and would not speak to him. The Heavenly Grandchild, grieved at this, made a song, saying:—

The sea-weed of the offing—

Though it may reach the shore:

The true couch

Is, alas! impossible.

Ah! ye dotterels of the beach In one writing it is said:—"The daughter of Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto, Ama-yorodzu-taku-hata chi-hata hime."

One version is:—"Yorodzu-hata-hime ko-dama-yori-hime no Mikoto was the child of Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto. This Goddess became the consort of Ame no Oshi-hone no Mikoto, and bore to him a child named Ama-no Ki-ho-ho-oki-se no Mikoto."

One version is:—"Katsu no haya-hi no Mikoto's child was Ama no Oho-mimi no Mikoto. This God took to wife Nigutsu hime, and had by her a child named Ninigi no Mikoto."

One version is:—"The daughter of Kami-mi-musubi no Mikoto, Taku-hata chi-hata hime, bore a child named Ho-no-ninigi no Mikoto."

One version is:—"Ama no Kise no Mikoto took to wife Ata-tsu hime, and had children, first Ho-no-akari no Mikoto, next Ho-no-yo-wori no Mikoto, and next Hiko-ho-ho-demi no Mikoto."

In one writing it is said:—"Masa-ya-a-katsu-katsu-no-haya-hi Ama no Oshi-ho-mimi no Mikoto took to wife Ama no yorodzu-taka-hata-chi-hata hime, daughter of Taka-mi-musubi no Mikoto, and by her as consort had a child named Ama-teru-kuni-teru Hiko-ho no akari no Mikoto. He is the ancestor of the Ohari no Muraji. The next child was Ama-no-nigishi-kuni-no-nigishi Ama-tsu-hiko-ho-no ninigi no Mikoto. This God took to wife Kono hana saku-ya-hime no Mikoto, daughter of Oho-yama-tsu-mi no Kami, and by her as consort had first a child named Ho-no-susori no Mikoto, and next Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto."

The elder brother Ho-no-susori no Mikoto had by nature a sea-gift; the younger brother Hiko-ho-ho-demi no Mikoto had by nature a mountain-gift.[87] In the beginning the two brothers, the elder and the younger, conversed together, saying:—"Let us for a trial exchange gifts." They eventually exchanged them, but neither of them gained aught by doing so. The elder brother repented his bargain, and returned to the younger brother his bow and arrows, asking for his fish-hook to be given back to him. But the younger brother had already lost the elder brother's fish-hook, and there was no means of finding it. He accordingly made another new hook which he offered to his elder brother. But his elder brother refused to accept it, and (II. 32.) demanded the old hook. The younger brother, grieved at this, forthwith took his cross-sword[88] and forged[89] from it new fish-hooks, which he heaped up in a winnowing tray, and offered to his brother. But his elder brother was wroth, and said:—"These are not my old fish-hook: though they are many, I will not take them." And he continued repeatedly to demand it vehemently. Therefore Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto's grief was exceedingly profound, and he went and made moan by the shore of the sea. There he met Shiho-tsutsu[90] no Oji.[91] The old man inquired of him saying:—"Why dost thou grieve here?" He answered and told him the matter from first to last. The old man said:—"Grieve no more. I will arrange this matter for thee." So he made a basket without interstices, and placing in it Hoho-demi no Mikoto, sank it in the sea. Forthwith he found himself at a pleasant strand, where he abandoned the basket, and, proceeding on his way, suddenly arrived at the palace of the Sea-God. This palace was provided with battlements and turrets, and had stately towers. Before the gate there was a well, and over the well there grew a many-branched cassia-tree,[92] with wide-spreading boughs and leaves. Now Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto went up to the foot of this tree and loitered about. After some time a beautiful woman appeared, (II. 33.) and, pushing open the door, came forth. She at length took a jewel-vessel and approached. She was about to draw water, when, raising her eyes, she saw him, and was alarmed. Returning within, she spoke to her father and mother, saying:—"There is a rare stranger at the foot of the tree before the gate." The God of the Sea thereupon prepared an eight-fold cushion and led him in. When they had taken their seats, he inquired of him the object of his coming. Then Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto explained to him in reply all the circumstances. The Sea-God accordingly assembled the fishes, both great and small, and required of them an answer. They all said:—"We know not. Only the Red-woman[93] has had a sore mouth for some time past and has not come." She was therefore peremptorily summoned to appear, and on her mouth being examined the lost hook was actually found.

After this, Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto took to wife the Sea-God's daughter, Toyo-tama[94]-hime, and dwelt in the sea-palace. For three years he enjoyed peace and pleasure, but still had a longing for his own country, and therefore sighed deeply from (II. 34.) time to time. Toyo-tama-hime heard this and told her father, saying:—"The Heavenly Grandchild often sighs as if in grief. It may be that it is the sorrow of longing for his country." The God of the Sea thereupon drew to him Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto, and addressing him in an easy, familiar way, said:—"If the Heavenly Grandchild desires to return to his country I will send him back." So he gave him the fish-hook which he had found, and in doing so instructed him, saying:—"When thou givest this fish-hook to thy elder brother, before giving to him call to it secretly, and say, "A poor hook." He further presented to him the jewel of the flowing tide and the jewel of the ebbing tide, and instructed him, saying:—"If thou dost dip the tide-flowing jewel, the tide will suddenly flow, and therewithal thou shalt drown thine elder brother. But in case thy elder brother should repent and beg forgiveness, if, on the contrary, thou dip the tide-ebbing jewel, the tide will spontaneously ebb, and therewithal thou shalt save him. If thou harass him in this way, thy elder brother will of his own accord render submission."

When the Heavenly Grandchild was about to set out on his return journey, Toyo-tama-hime addressed him, saying:—"Thy handmaiden is already pregnant, and the time of her delivery is not far off. On a day when the winds and waves are raging, I will surely come forth to the sea-shore, and I pray thee that thou wilt make for me a parturition house,[95] and await me there."

When Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto returned to his palace, he complied implicitly with the instructions of the Sea-God, and the elder brother, Ho-no-susori no Mikoto, finding himself in the utmost straits, of his own accord admitted his offence, and (II. 35.) said:—"Henceforward I will be thy subject to perform mimic dances for thee. I beseech thee mercifully to spare my life." Thereupon he at length yielded his petition, and spared him.[96] This Ho-no-susori no Mikoto was the first ancestor of the Kimi of Wobashi in Ata.

After this Toyo-tama-hime fulfilled her promise, and, bringing with her her younger sister, Tama-yori-hime, bravely confronted the winds and waves, and came to the sea-shore. When the time of her delivery was at hand, she besought Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto, saying:—"When thy handmaiden is in travail, I pray thee do not look upon her." However, the Heavenly Grandchild could not restrain himself, but went secretly and peeped in. Now Toyo-tama-hime was just in childbirth, and had changed into a dragon.[97] She was greatly ashamed, and said:—"Hadst thou not disgraced me, I would have made the sea and land communicate with each other, and for ever

prevented them from being sundered. But now that thou hast disgraced me, wherewithal shall friendly feelings be knit together?" So she wrapped the infant in rushes, and abandoned it on the sea-shore. Then she barred the sea-path, and passed away.[98] Accordingly the child was called Hiko-nagisa-take-u-gaya-fuki-ahezu[99] no Mikoto.

A long time after, Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto died, and was buried in the Misasagi on the summit of Mount Takaya in Hiuga.

(II. 36.) In one writing it is said:—"The elder brother Ho-no-susori no Mikoto had acquired a mountain-gift. Now the elder and younger brothers wished to exchange gifts, and therefore the elder brother took the bow which was of the gift of the younger brother, and went to the mountain in quest of wild animals. But never a trace of game did he see. The younger brother took the fish-hook of his elder brother's gift, and with it went a fishing on the sea, but caught none at all, and finally lost his fish-hook. Then the elder brother restored his younger brother's bow and arrows, and demanded his own fish-hook. The younger brother was sorry, and of the cross-sword which he had in his girdle made fish-hooks, which he heaped up in a winnowing tray, and offered to his elder brother. But the elder brother refused to receive them, saying:—'I still wish to get the fish-hook of my gift.' Hereupon Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto, not knowing where to look for it, only grieved and made moan. He went to the sea-shore, where he wandered up and down lamenting. Now there was an old man, who suddenly came forward, and gave his name as Shiho-tsuchi no Oji. He asked him, saying:—'Who art thou, my lord, and why dost thou grieve here?' Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto told him all that had happened. Whereupon the old man took from a bag a black comb, which he flung upon the ground. It straightway became changed into a multitudinous[100] clump of bamboos. Accordingly he took these bamboos and made of them a coarse basket with wide meshes, in which he placed Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto, and cast him into the sea."

One version says:—"He took a katama without interstices, and made of it a float, to which he attached Hoho-demi by a cord and sunk him." [The term katama means what is now called a bamboo-basket.]

Now there is in the bottom of the sea a natural "Little-shore of delight." Proceeding onwards, along this shore, he arrived of a sudden at the palace of Toyo-tama-hiko, the God of the Sea. This palace had magnificent gates and towers of exceeding beauty. Outside the gate there was a well, and beside the well was a cassia-tree. He approached (II. 37.) the foot of this tree, and stood there. After a while a beautiful woman, whose countenance was such as is not anywhere to be seen, came out from within, followed by a bevy of attendant maidens. She was drawing water in a jewel-urn, when she looked up and saw Hoho-demi no Mikoto. She was startled, and returning, told the God, her father, saying:—'At the foot of the cassia-tree without the gate, there is a noble stranger of no ordinary build. If he had come down from Heaven, he would have had on him the filth of Heaven; if he had come from Earth, he would have had on him the filth of Earth. Could he be really the beautiful prince of the sky?'

One version says:—"An attendant of Toyo-tama-hime was drawing water in a jewel-pitcher, but she could not manage to fill it. She looked down into the well, when there shone inverted there the smiling face of a man. She looked up and there was a beautiful God leaning against a cassia-tree. She accordingly returned within, and informed her mistress.

Hereupon Toyo-tama-hiko sent a man to inquire, saying:—'Who art thou, O stranger, and why hast thou come here?' Hoho-demi no Mikoto answered and said:—'I am the grandchild of the Heavenly Deity,' and ultimately went on to give the reason of his coming.

Then the God of the Sea went out to meet him. He made him obeisance, and led him within, where he inquired courteously of his welfare, and gave him to wife his daughter, Toyo-tama-hime. Therefore he remained and dwelt in the palace of the sea. Three years passed, after which Hoho-demi no Mikoto sighed frequently, and Toyo-tama-hime asked him, saying:—'Does the Heavenly Grandchild perchance wish to return to his native land?' He answered and said:—'It is so.' Toyo-tama-hime forthwith told the God her father, and said:—'The noble guest who is here wishes to return to the upper (II. 38.) country.' Hereupon the God of the Sea assembled all the fishes of the sea, and asked of them the fish-hook. Then one fish answered and said:—'The Red-woman[101] (also called the Red Tahi) has long had an ailment of the mouth. I suspect that she has swallowed it.' So the Red-woman was forthwith summoned, and on looking into her mouth, the hook was still there. It was at once taken and delivered to Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto, with these instructions:—'When thou givest the fish-hook to thy elder brother, thou must use this imprecation: "The origin of poverty: the beginning of starvation: the root of wretchedness." Give it not to him until thou hast said this. Again, if thy brother cross the sea, I will then assuredly stir up the blasts and billows, and make them overwhelm and vex him.' Thereupon he placed Hoho-demi no Mikoto on the back of a great sea-monster, and so sent him back to his own country.

At another time, before this, Toyo-tama-hime spoke in an easy, familiar way, and said:—'Thy handmaid is with child. Some day, when the winds and waves are boisterous, I will come forth to the sea-shore, and I pray thee to construct for me a parturition-house, and to await me there.'

After this, Toyo-tama-hime fulfilled her promise to come, and spake to Hoho-demi no Mikoto, saying:—'To-night thy handmaiden will be delivered. I pray thee, look not on her.' Hoho-demi no Mikoto would not hearken to her, but with a comb[102] he made a light, and looked at her. At this time Toyo-tama-hime had become changed into an enormous sea-monster of eight fathoms, and was wriggling about on her belly. She at last was angry that she was put to shame, and forthwith went straight back again to her native sea, leaving behind her younger sister Tama-yori-hime (II. 39.) as nurse to her infant. The child was called Hiko-nagisa-take-u-gaya-fuki-ayezu no Mikoto, because the parturition-house by the sea-shore was all thatched with cormorants' feathers, and the child was born before the tiles had met. It was for this reason that he received this name."[103]

One version says:—"Before the gate there was a beautiful well, and over the well there grew a cassia-tree with an hundred branches. Accordingly Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto sprang up into that tree and stood there. At this time, Toyo-tama-hime, the daughter of the God of the Sea, came with a jewel-bowl in her hand and was about to draw water, when she saw in the well the reflection of a man. She looked up and was startled, so that she let fall the bowl, which was broken to pieces. But without regard for it, she returned within and told her parents, saying:—'I have seen a man on the tree which is beside the well. His countenance is very beautiful, and his form comely. He is surely no ordinary person.' When the God, her father, heard this, he wondered. Having prepared an eight-fold cushion, he went to meet him, and brought him in. When they were seated, he asked the reason of his coming, upon which he answered and told him all his case. Now the God of the Sea at once conceived pity for him, and summoning all the broad of fin and narrow of fin, made inquiry of them. They all said:—"We know not. Only the Red-woman has an ailment of the mouth and has not come.' [Another version is:—'The Kuchi-me[104] has an ailment of the mouth.'] So she was sent for in all haste, and on searching her mouth, the lost fish-hook was at once found. Upon this the God of the Sea chid her, saying:—'Thou Kuchime! Henceforward thou shalt not be able to swallow a bait, nor shalt thou be allowed to have a place at the table of the Heavenly Grandchild.' This is the reason why the fish kuchime is not among the articles of food set before the Emperor.

When the time came for Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto to take his departure, the God of the Sea spake to him, saying:—'I am rejoiced in my inmost heart that the Heavenly Grandchild has now been graciously pleased to visit me. (II. 40.) When shall I ever forget it?' So he took the jewel which when thought of makes the tide to flow, and the jewel which when thought of makes the tide to ebb, and joining them to the fish-hook, presented them, saying:—'Though the Heavenly Grandchild may be divided from me by eight-fold windings (of road), I hope that we shall think of each other from time to time. Do not therefore throw them away.' And he taught him, saying:—'When thou givest this fish-hook to thy elder brother, call it thus:—'A hook of poverty, a hook of ruin, a hook of downfall.' When thou hast said all this, fling it away to him with thy back turned, and deliver it not to him face to face. If thy elder brother is angry, and has a mind to do thee hurt, then produce the tide-flowing jewel and drown him therewith. As soon as he is in peril and appeals for mercy, bring forth the tide-ebbing jewel and therewith save him. If thou dost vex him in this way, he will of his own accord become thy submissive vassal.' Now Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto, having received the jewels and the fish-hook, came back to his original palace, and followed implicitly the teaching of the Sea-God. First of all he offered his elder brother the fish-hook. His elder brother was angry and would not receive it. Accordingly the younger brother produced the tide-flowing jewel, upon which the tide rose with a mighty overflow, and the elder brother was drowning. Therefore he besought his younger brother, saying:—'I will serve thee as thy slave. I beseech thee, spare my life.' The younger brother then produced the tide-ebbing jewel, whereupon the tide ebbed of its own accord, and the elder brother was restored to tranquillity. After this the elder brother changed his former words, and said:—'I am thy elder brother. How can an elder brother serve a younger brother?' Then the younger brother produced the tide-flowing jewel, which his elder brother seeing, fled up to a high mountain. Thereupon the tide also submerged the mountain. The elder brother climbed a lofty tree, and thereupon the tide also submerged the tree. The elder brother was now at an extremity, and had nowhere to (II. 41.) flee to. So he acknowledged his offence, saying:—'I have been in fault. In future my descendants for eighty generations shall serve thee as thy mimes in ordinary. [One version has 'dog-men.'] I pray thee, have pity on me.' Then the younger brother produced the tide-ebbing jewel, whereupon the tide ceased of its own accord. Hereupon the elder brother saw that the younger brother was possessed of marvellous powers, and at length submitted to serve him.

On this account the various Hayato descended from Ho no susori no Mikoto to the present time do not leave the vicinity of the enclosure of the Imperial Palace, and render service instead of barking dogs[105]

This was the origin of the custom which now prevails of not pressing a man to return a lost needle."[106]

In one writing it is said:—"The elder brother, Ho no susori no Mikoto, was endowed with a sea-gift, and was therefore called Umi no sachi-hiko:[107] the younger brother, Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto, was endowed with a mountain-gift, (II. 42.) and was therefore called Yama no sachi-hiko. Whenever the wind blew and the rain fell, the elder brother lost his gain, but in spite of wind and rain the younger brother's gain did not fail him. Now the elder brother spoke to the younger brother, saying:—'I wish to make trial of an exchange of gifts with thee.' The younger brother consented, and the exchange was accordingly made. Thereupon the elder brother took the younger brother's bow and arrows, and went a-hunting to the mountain: the younger brother took the elder brother's fish-hook, and went on the sea a-fishing. But neither of them got anything, and they came back empty-handed. The elder brother accordingly restored to the younger brother his bow and arrows, and demanded back his own fish-hook. Now the younger brother had lost the fish-hook in the sea, and he knew not how to find it. Therefore he made other new fish-hooks, several thousands in number, which he offered to his elder brother. The elder brother was angry, and would not receive them, but demanded importunately the old fish-hook, etc., etc. Then the younger brother went to the sea-shore and wandered about, grieving and making moan. Now there was there a river wild-goose which had become entangled in a snare, and was in distress. He took pity on it, and loosing it, let it go. Shortly after there appeared Shiho tsutsu no Oji. He came and made a skiff of basket-work without interstices, in which he placed Hoho-demi no Mikoto and pushed it off into the sea, when it sank down of its own accord, till of a sudden there appeared the Pleasant Road. So he went on along this road, which in due course led him to the palace of the Sea-God. Then the Sea-God came out himself to meet him, and invited him to enter. He spread eight layers of sea-asses'[108] skins, on which he made him to sit, and with a banquet of tables of a hundred, which was already prepared, he fulfilled the rites of hospitality. Then he inquired of him in an easy manner:—'Wherefore has the Grandchild of the Heavenly Deity been graciously pleased to come hither?'"

[One version has:—"A little while ago my child came and told me that the Heavenly Grandchild was mourning by the sea-shore. Whether this be true or false I know not, but perhaps it may be so."]

Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto related to him all that had happened from first to last. So he remained there, and the Sea-God gave him his daughter Toyo-tama-hime to wife. At length, when three years had passed in close and (II. 43.) warm affection, the time came for him to depart. So the Sea-God sent for the tahi, and on searching her mouth found there the fish-hook. Thereupon he presented the fish-hook to Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto, and instructed him thus:—'When thou givest this to thy elder brother thou must recite the following:—"A big hook, an eager hook, a poor hook, a silly hook." After saying all this, fling it to him with a back-handed motion.' Then he summoned together the sea-monsters, and inquired of them, saying:—'The Grandchild of the Heavenly Deity is now about to take his departure homewards. In how many days will you accomplish this service?' Then all the sea-monsters fixed each a number of days according to his own length. Those of them which were one fathom long of their own accord said:—'In the space of one day we will accomplish it.' The one-fathom sea-monsters were accordingly sent with him as his escort. Then he gave him two precious objects, the tide-flowing jewel and the tide-ebbing jewel, and taught him how to use them. He further instructed him, saying:—'If thy elder brother should make high fields, do thou make puddle fields; if thy elder brother make puddle fields, do thou make high fields.' In this manner did the Sea-God in all sincerity lend him his aid. Now Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto, when he returned home, followed implicitly the God's instructions, and acted accordingly. When the younger brother produced the tide-flowing jewel, the elder brother forthwith flung up his hands in the agony of drowning. But when, on the other hand, he produced the tide-ebbing jewel, he was relieved, and recovered. After that Hi no susori no Mikoto pined away from day to day, and lamented, saying:—'I have become impoverished.' So he yielded submission to his younger brother.

(II. 44.) Before this Toyo-tama-hime spake to the Heavenly Grandchild, saying:—'That which thy handmaid has conceived is the offspring of the Heavenly Grandchild. How could I give birth to it in the midst of the ocean? Therefore when the time of my delivery comes, I will surely betake myself to my lord's abode, and it is my prayer that thou shouldst build me a house by the sea-side and await me there.' Therefore Hiko-ho-ho-demi no Mikoto, as soon as he returned to his own country, took cormorants' feathers, and with them as thatch, made a parturition-house. But before the tiling of the house was completed, Toyo-tama-hime herself arrived, riding on a great tortoise, with her younger sister Tama-yori-hime, and throwing a splendour over the sea. Now the months of her pregnancy were already fulfilled, and the time of her delivery was urgent. On this account she did not wait till the thatching of the house was completed, but went straight in and remained there. Then she spake quietly to the Heavenly Grandchild, saying:—'Thy handmaid is about to be delivered. I pray thee do not look on her.' The Heavenly Grandchild wondered at these words, and peeped in secretly, when behold, she had become changed into a great sea-monster of eight fathoms. Now she was aware that the Heavenly Grandchild had looked in upon her privacy, and was deeply ashamed and resentful. When the child was born, the Heavenly Grandchild approached and made inquiry, saying:—'By what name ought the child to be called?' She answered and said:—'Let him be called Hiko-nagisa-take-u-gaya-fuki-ahezu no Mikoto.'[109] Having said so, she took her departure straight across the sea. Then Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto made a song, saying:—

Whatever befals me,

Ne'er shall I forget my love

With whom I slept

In the island of wild-ducks—

The birds of the offing."[110](II. 45.) Another account says:—"Hiko-ho-ho-demi no Mikoto took other women and made them wet-nurses, bathing-women, boiled-rice-chewers, and washerwomen.[111] All these various Be were provided for the respectful nurture of the infant. The provision at this time, by means of other women, of milk for the nurture of the august child was the origin of the present practice of engaging temporarily wet-nurses to bring up infants.

After this, when Toyo-tama-hime heard what a fine boy her child was, her heart was greatly moved with affection, and she wished to come back and bring him up herself. But she could not rightly do so, and therefore she sent her younger sister Tama-yori-hime to nurture him. Now when Toyo-tama-hime sent Tama-yori-hime, she offered (to Hoho-demi no Mikoto) the following verse in answer:—

Some may boast

Of the splendour

Of red jewels,But those worn by my Lord—

It is they which are admirable.[112]These two stanzas, one sent, and one in reply, are what are termed age-uta."[113]

In one writing it is said:—"The elder brother, Ho no susori no Mikoto had a sea-gift, while the younger brother, Ho no ori no Mikoto, had a mountain gift, etc., etc.

(II. 46.) The younger brother remained by the sea-shore grieving and making moan, when he met with Shiho-tsutsu no Oji, who inquired of him, saying:—'Why dost thou grieve in this way?' Ho no ori no Mikoto answered and said, etc., etc.

The old man said:—'Grieve no longer. I will devise a plan.' So he unfolded his plan, saying:—'The courser on which the Sea-God rides is a sea-monster eight fathoms in length, who with fins erect stays in the small orange-tree house. I will consult with him.' So he took Ho no ori no Mikoto with him, and went to see the sea-monster. The sea-monster then suggested a plan, saying:—'I could bring the Heavenly Grandchild to the Sea-Palace after a journey of eight days, but my King has a courser, a sea-monster of one fathom, who will without doubt bring him thither in one day. I will therefore return and make him come to thee. Thou shouldst mount him, and enter the sea. When thou enterest the sea, thou wilt in due course find there "the Little-shore of delight." Proceed along this shore and thou wilt surely arrive at the palace of my King. Over the well at the palace gate there is a multitudinous branching cassia-tree. Do thou climb up on to this tree and stay there.' Having so said, he entered into the sea, and departed. Accordingly the Heavenly Grandchild, in compliance with the sea-monster's words, remained there, and waited for eight days, when there did indeed appear to him a sea-monster of one fathom. He mounted on it, and entered the sea, where he followed in every particular the former sea-monster's advice. Now there appeared an attendant of Toyo-tama-hime, carrying a jewel-vessel, with which she was about to draw water from the well, when she espied in the bottom of the water the shadow of a man. She could not draw water, and looking up saw the Heavenly Grandchild. Thereupon she went in and informed the King, saying:—'I had thought that my Lord alone was supremely handsome, but now a stranger has appeared who far excels him in beauty.' When the Sea-God heard this, he said:—'I will try him and see.' So he prepared a threefold dais. Thereupon the Heavenly Grandchild wiped both his feet at the first step of the dais. At the middle one he placed both his hands to the ground; at the inner one he sat down at his ease[114] upon the cushion covering the true couch. When the Sea-God saw this, he knew that this was the grandchild of the Heavenly Deity, and treated (II. 47.) him with more and more respect, etc., etc.

The Sea-God summoned the Akame and the Kuchime, and made inquiry of them. Then the Kuchime drew a fish-hook from her mouth and respectfully delivered it to him. [The Akame is the Red Tahi and the Kuchime is the Nayoshi.][115] The Sea-God then gave the fish-hook to Hiko-hoho-demi no Mikoto, and instructed him, saying:—'When thy elder brother's fish-hook is returned to him, let the Heavenly Grandchild say:—"Let it be to all thy descendants, of whatever degree of relationship, a poor hook, a paltry poor hook." When thon hast thus spoken, spit thrice, and give it to him. Moreover, when thy elder brother goes to sea a-fishing, let the Heavenly Grandchild stand on the sea-shore and do that which raises the wind. Now that which raises the wind is whistling. If thou doest so, I will forthwith stir up the wind of the offing and the wind of the shore, and will overwhelm and vex him with the scurrying waves.' Ho no ori no Mikoto returned, and obeyed implicitly the instructions of the God. When a day came on which the elder brother went a-fishing, the younger brother stood on the shore of the sea, and whistled. Then there arose a sudden tempest, and the elder brother was forthwith overwhelmed and harassed. Seeing no means of saving his life, he besought his younger brother from afar, saying:—'Thou hast dwelt long in the ocean-plain, and must possess some excellent art. I pray thee teach it to me. If thou save my life, my descendants of all degrees of relationship shall not leave the neighbourhood of thy precinct, but shall act as thy mime-vassals.' Thereupon the younger brother left off whistling, and the wind again returned to rest. So the elder brother recognized the younger brother's power, and freely admitted his fault. But the younger brother was wroth, and would hold no converse with him. Hereupon the elder brother, with nothing but his waistcloth on, and smearing the palms of his hands and (II. 48.) his face with red earth, said to his younger brother:—'Thus do I defile my body, and make myself thy mime for ever.' So kicking up his feet, he danced along and practised the manner of his drowning struggles. First of all, when the tide reached his feet, he did the foot-divination;[116] when it reached his knees, he raised up his feet; when it reached his thighs, he ran round in a circle; when it reached his loins, he rubbed his loins; when it reached his sides, he placed his hands upon his breast; when it reached his neck, he threw up his hands, waving his palms. From that time until now, this custom has never ceased.

Before this, Toyo-tama-hime came forth, and when the time came for her delivery, she besought the Heavenly Grandchild, saying, etc., etc.

The Heavenly Grandchild did not comply with her request, and Toyo-tama-hime resented it greatly, saying:—'Thou didst not attend to my words, but didst put me to shame. Therefore from this time forward, do not send back again any of the female servants of thy handmaid who may go to thy place, and I will not send back any of thy servants who may come to my place.' At length she took the coverlet of the true couch and rushes, and wrapping her child in them, laid him on the beach. She then entered the sea and went away. This is the reason (II. 49.) why there is no communication between land and sea."

One version says:—"The statement that she placed the child on the beach is wrong. Toyo-tama-hime no Mikoto departed with the child in her own arms. Many days after, she said:—'It is not right that the offspring of the Heavenly Grandchild should be left in the sea,' so she made Tama-yori-hime to take him, and sent him away. At first, when Toyo-tama-hime left, her resentment was extreme, and Ho no ori no Mikoto therefore knew that they would never meet again, so he sent her the verse of poetry which is already given above."

Hiko-nagisa-take-u-gaya-fuki-ahezu no Mikoto took his aunt Tama-yori-hime as his consort, and had by her in all four male children, namely, Hiko-itsu-se[117] no Mikoto, next Ina-ihi[118] no Mikoto, next Mi-ke-iri-no[119] no Mikoto, and next Kamu-yamato-Ihare-biko no Mikoto. Long after, Hiko-nagisa-take-u-gaya-fuki-ahezu no Mikoto died, in the palace of the western country, and was buried in the Misasagi on the top of Mount Ahira in Hiuga.

One writing says:—"His first child was Hiko-itsu-se no Mikoto, the next Ina-ihi no Mikoto, the next Mi-ke-iri-no no Mikoto, and the next Sano no Mikoto, also styled Kamu[120]-yamato-Ihare-biko no Mikoto. Sano was the name by which he was called when young. Afterwards when he had cleared and subdued the realm, and had control of the (II. 50.) eight islands, the title was added of Kamu-yamato Ihare-biko no Mikoto."

In one writing it is said:—"His first child was Itsu-se no Mikoto, the next Mikeno no Mikoto, the next Ina-ihi no Mikoto, and the next Ihare-biko no Mikoto, also styled Kamu-yamato Ihare-biko Hoho-demi no Mikoto."

In one writing it is said:—"First he had Hiko-itsuse no Mikoto, next Ina-ihi no Mikoto, next Kamu-yamato Ihare-biko Hoho-demi no Mikoto, next Waka-mi-ke-no no Mikoto."

In one writing it is said:—"First he had Hiko-itsu-se no Mikoto, next Ihare-biko Hoho-demi no Mikoto, next Hiko Ina-ihi no Mikoto, next Mi-ke-iri-no no Mikoto."

- ↑ Taku-hata, paper-mulberry loom (cloth).

- ↑ The interpretation of this name is doubtful. See Ch. K., p. 106.

- ↑ Great-husband-boiled-rice-of-Mikuma of master.

- ↑ Take, brave, is merely a honorific. It is prefixed to several names of Deities.

- ↑ Heaven-young-prince.

- ↑ Heaven-of-country-jewel.

- ↑ Lower-shine-princess.

- ↑ Real-country-jewel.

- ↑ Na-naki. This word is written here as if the meaning were "nameless." But in the "Kojiki" (see Ch. K., p. 95), characters are used which give it the sense of name-crying, i.e. calling out its own name. The old Japanese for pheasant is kigishi or kigisu. Comparing this with uguhisu (the Japanese nightingale), kakesu (the jay), kirigirisu (the grasshopper), karasu (the crow), and hototogisu (a kind of cuckoo), it becomes evident that kigisu is an onomatopoetic word. Su is for suru, to do. The Corean for a pheasant is kiöng, no doubt also an onomatope.

- ↑ Heavenly-spying-woman.

- ↑ We have here a glimpse of the ancient Japanese funeral ceremonies.

"Head-hanging bearers" is a literal translation of the Chinese characters. The interlinear Kana renders them by the obsolete word kisari-mochi, of obscure meaning. An ancient commentator says that these were persons who accompanied the funeral, bearing on their heads food for the dead, which is perhaps correct. The brooms were probably for sweeping the road before the procession. The pounding-women pounded the rice for the guests, and perhaps also for the offerings to the deceased. By mourners are meant paid mourners.

To these Hirata adds from old books the wata-dzukuri or tree-fibre carders, the kites (the fibre being to fill up the vacant space in the coffin), and the fleshers (for food offered to the deceased), an office given to the crow. Compare also Ch. K., p. 97.

The student of folk-lore will not think it frivolous of me to cite here the English story of the Death and Burial of Cock Robin, where the birds officiate in various capacities at a funeral.

"Sang dirges." Hirata condemns this as a Chinese importation. He prefers the "Kojiki" version, which says that "they made merry," and explains that this was with the object of recalling the dead to life, perhaps in imitation of the Gods dancing and making merry in order to entice the Sun-Goddess from her rock-cave. Compare the following passage from a Chinese History of the Han (A.D. 25–220) Dynasty.

In Japan "Mourning lasts for some ten days only, during which time the members of the family weep and lament, whilst their friends come singing, dancing and making music."

The mortuary house was required for the temporary disposal of the dead, while the sepulchral mound with its megalithic chamber was being constructed. Vide Index—Misasagi.

- ↑ No satisfactory explanation of this name.

- ↑ Great-leaf-mower.

- ↑ Futsu is explained by Hirata as an onomatopoetic word like the modern futtsuri for the abrupt snapping sound produced when anything is cleanly cut or broken off. Nushi means master.

- ↑ Iha-tsutsu. Iha is rock, tsutsu probably a honorific=elder. Wo is male; me, female.

- ↑ Iha-saku means rock-split; ne-saku, root-split.

- ↑ Mika is explained by Hirata as the same as ika, terrible; haya-hi means swift sun.

- ↑ Idzu no wo-bashiri, lit. dread-of-male-run.

- ↑ Take-mika-dzuchi. Take is brave. Mika-dzuchi is identified with ika-dzuchi, thunder.

- ↑ Wobama.

- ↑ Hirata points out the appropriateness of this name, which means "Yes or no?—shanks," to a messenger sent to ask a question.

- ↑ The Chinese character indicates a communication from an Emperor.

"Went off" is the same character as is translated "withdraw" above. Hirata understands this of his death. The whole episode is related quite differently in the "Kojiki." Vide Ch. K., p. 101.

Enclosures of bamboo are used at the present day to trap fishes, but it is not very clear why one is introduced here.

- ↑ A mere epithet or pillow-word (makura-kotoba) of eighty.

- ↑ The eighty-road-windings are put for a long journey, i.e. to Yomi or Hades, or rather for Yomi itself.

- ↑ i.e. died.

- ↑ Kagase-wo. Wo means male. Kaga is obviously connected with kagayaku, to shine. This is the only Star-God mentioned in Japanese myth, and it may be noted that little honour is shown him. He is described as a conquered rebel, and has neither Kami nor Mikoto affixed to his name. The only stars mentioned in the "Kojiki" or "Nihongi" are Venus, the Pleiades, and the Weaver or Star α Lyrae, the latter being connected with a Chinese legend.

The Weaver-God is literally, if we follow the Chinese character, the God of Japanese striped stuffs. The interlinear "Kana" gives Shidzuri or Shidori, from shidzu, cloth, and ori, weave, which is doubtless correct. Take-ha-dzuchi is brave-leaf-elder. It is not clear that this Weaver-God is the same as the Weaver star.

- ↑ The interlinear gloss has idzu, an obsolete word which means awful, holy, sacred. It is, I would suggest, the same root which appears in the name of the province Idzu-mo and in Idzu-shi in Tajima, also a seat of Shintō worship. Mo means quarter, as in yomo, the four quarters, everywhere, and shi is for ishi, stone. See Index—Idzu.

- ↑ It is this word which forms the second part of Kumaso, the general name of the tribes which inhabited the south of Kiushiu.

- ↑ Thing-excel-country-excel. Long-narrow.