Once a Week (magazine)/Series 1/Volume 3/A gossip about organs

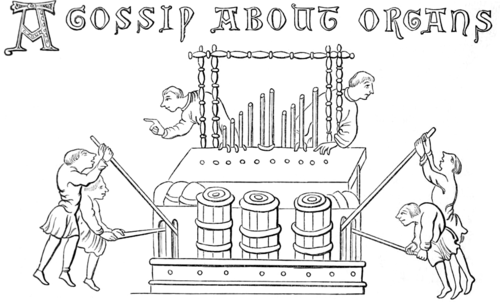

Hand Organ, from the Nuremberg Chronicle.We wonder how many, out of the thousands to whom the tones of the organ are so familiar, ever give more than a passing thought to it, or reflect on the science and skill that have been lavished on it, from the time of the reed-pipes of the ancients up till now, when it has become the most gigantic and complex musical instrument of modern times. Indeed, many amateurs, fond as they are of music, and of church-music in particular, are surprised when they first begin to find out what a vast amount of machinery is packed into such a small compass, and what a number of abstruse and scientific principles have to be attended to before they can extract even one sweet sound. The earliest organ was probably nothing more than a series of reeds blown by the mouth, a proceeding which was found so tiresome, that it was not long before the bellows came into use, so as to ensure a constant supply of wind; but even then it was only a rudiment of the present instrument, since it was not till the eleventh century that a keyboard was first added to the one in Magdeburgh Cathedral. Here was an epoch in the history of sacred music—the lowest step of that platform of divine harmony which has since risen in such noble strains, and which is still ever ascending. What masters in the art have played out their lives since then, filling the world with the glorious creations of their genius!

It will not be uninteresting to the general reader if we endeavour to sketch briefly the manner in which the interior of the organ is arranged—the popular notion of all that is necessary being, some pipes, wind, and a person to play. After all, this may be a simple definition: but the curious and compact way in which so much delicate workmanship is put together is surely worthy of a little attention. Of course there is every variety both in size, volume and cost; but we will take a sample of the ordinary church-organ and examine it at our leisure. What is generally called a good sized one would be more correctly spoken of as three or four harmoniously put together into a case, and not only involving distinct sets of pipes, but also distinct sets of keys upon which to play. Thus, in one case, we have frequently three, and in very large organs, four sets of finger-keys, or manuals, termed the great, the swell, and the choir organs; while the corresponding set to be played by the feet are called pedals. The grand desideratum, the wind, was always supplied by bellows, of course; but even in this point, immense improvements have been effected. Bellows are of two kinds,—diagonal and horizontal; the former so called, because, when blown, one end ascends while the other is stationary, giving it a wedge-like appearance, while the horizontal bellows always preserves an uniformly level surface.

Almost all the old organs were fitted with the first kind, but the inconvenience was that the supply of wind was so irregular as to necessitate the use of several pairs (the organ at St. Sulpice, in Paris, having actually fourteen), whereas one pair of horizontal bellows is equivalent to at least half-a-dozen of the diagonal species. The wind which has been collected is then distributed by wooden pipes, termed wind-trunks, into a shallow box or wind-chest, where it accumulates ready for more minute dispersion to the various portions of the instrument. Now the mechanism becomes a little more intricate. The roof of the wind-chest is formed by what is called the sound-board, on which are a certain number of grooves or channels perforated with holes, so as to allow of the conducting of the wind to the several pipes. Nevertheless, as matters stand at present, the moment that the wind is introduced, all the pipes would speak at once, to obviate which a moveable piece of wood, or sounding-pallet is inserted in the groove, the control over it being exercised by means of a wire connected with the key-note: the result is, that when the note is pressed, the wire acts on the pallet, allowing the air to escape into that particular groove, and thus produces a musical note, or, we may say, notes; for, as there are several pipe-holes to each groove, all those pipes would sound simultaneously. This, however, is prevented by a series of sliders, perforated in such a manner as to correspond with the holes of the sounding-board, and table below it, and by this means all the pipes not wanted can be shut off at will. The keys of the manuals are connected with the sounding-pallets by rather complicated mechanism, into which it would be tedious to enter now, although it does not always follow that they must be close to each other, an instance of which, Mr. Hopkins tells us, is to be found in Prince Albert’s organ at Windsor, where the keys are placed twenty-two feet from the rest of the instrument, while in that of the Church of St. Alessandro, there is a long movement of 115 feet.

We must not forget to mention, ere we go any further, that the sliders which admit or shut the wind off from the pipes, being all placed inside, and out of the reach of the player, are controlled externally by the use of the draw-stop; and, as everybody knows, the size of an organ is generally estimated by the number of the stops. Those that are apportioned to each manual of the organ, are usually acted upon only by the keys of that manual, but by the invention of the coupler, the stops of any two manuals can be brought into connection; for instance, we see in descriptions of organs, swell coupler too great, or choir too great, &c., implying that by this means the swell or choir manuals can be brought under the same action as the great.

It is obvious that a tremendous power is thus put into the hands of the performer, who is able at will to pile up Pelion on Ossa, and thunder forth his music to the loudest. As another instance of economising in the labour of playing, we may mention the composition pedals by which a certain number of stops are pulled out simultaneously with the working of the pedal, without the necessity of the organist taking his hands off from the keys.

The most important department of the organ is that of the pipes, a department of all others which shows the particular stamp of the builder, the most eminent of whom can often be recognised by their tone.

Pipes are divided into two classes—those made of metal and those of wood; the metal being either pure tin or a compound of tin and lead.

Mr. Walker is very fond of using a composition called spotted metal, in which there is about one-third of tin; and very nice it looks, particularly for front speaking-pipes, where no money can be afforded for external decorations. Both metal and wooden pipes vary considerably in shape and size, depending entirely on the quality and quantity of sound to be produced, and the ingenuity expended upon them may be imagined when, as in the Panopticon organ, sixty stops have to be inserted, implying an aggregate of 4000 pipes. The swell is simply a smaller organ contained in the large one, and shut up in a box, the front of which works like a Venetian-blind, allowing the sound to increase or diminish as the shutters are moved up or down; but, in small instruments, with only one row of keys, a substitute is used, of a large shutter placed immediately behind the show or speaking-pipes, and worked in the same way by a pedal.

The first European organ of which we have any account, appears to have been sent to Pepin, king of the Franks, by the Byzantine emperor, Constantine, in 757. It must have been a queer concern, for it was not until the end of the eleventh century that the key-board was introduced, each key being five inches wide, so as to allow them to be beaten down by the fist. Indeed, even so late as 1529, we find that a new organ was bought for Holbeach church, in Lincolnshire, for the magnificent sum of 3l. 6s. 8d.; and a still more splendid one put up in Trinity College, Oxford, a few years later, for 10l. Now-a-days the competition amongst our English towns as to which shall possess the finest organ, has run the prices up to 3000l. or 4000l. It is curious to observe how many continental cathedrals have more than one instrument; and, in fact, it is unusual to find a church of any size without two or more. That of St. Antonio, at Padua, has four large ones; while St. Mark, at Venice, has two large, and four small portable ones, which can be easily moved about; and, if we recollect rightly, there are also six in the cathedral at Seville.

Their usual position in English churches was on the gallery at the west end, facing the communion-table, and in cathedrals between the nave and choir—a situation, by the way, which came into fashion after the Reformation, and so far objectionable, that it interferes sadly with the general view; but in most new churches they are generally placed upon or a little above the ground floor, either in the chancel or at the side of the choir. In the Lutheran church at Dresden, the chapels at Versailles and the Tuileries, and at Little Stanmore, near Edgeware, the organs are put at the east end, just over the communion-table; while in the church at Courtray, it is divided into two portions, so as to allow a window to be visible in the middle, while the keys and bellows are placed underneath it.

There is a striking difference in the appearance of the organ cases of the present day, as compared with the earlier ones. All the decoration now is expended on the outside pipes, which are painted and illuminated in a manner wonderful to behold; while the old builders lavished their taste on the carving of the wood. Indeed, this was often carried to a ludicrous extent, particularly in an organ alluded to by Hopkins, who tells us, that not content with innumerable carvings of angels and heavenly hosts, the inventive artist added trumpets and kettledrums, which were played by the same angels, while a conductor with a huge pair of wings beat time. To such a pitch was this extravagance carried, that there was even one stop, which when pulled out, caused a fox’s tail to fly out into the face of the inquisitive meddler. Of more chaste appearance than these are the organ in the church of St. Nicholas, at Prague, in which all the ornaments and framework are of white marble, and that in the Escurial, at Madrid, said to be of solid silver.

Instruments are considerably cheaper than they used to be; for we are told that Father Smith, the most celebrated of the old builders, had 2000l. for the organ in St. Paul’s, which had only 28 stops; while for a trumpet stop in Chichester Cathedral, Byfield was paid 50l. We must remember, however, that many are only half-stops, that is, furnished with pipes for half the notes, whereas these old ones always ran through the complete scale. For many years the Haarlem organ, which cost 10,000l., was considered the largest and most complete in the world; but it has been frequently surpassed, both in size and tone. It contains 60 sounding stops, and 4088 pipes, one of which is 15 inches in diameter and 40 feet long; but in the Birmingham Town Hall there is one of 12 feet in circumference, which measures 224 cubic feet in the interior. The organ in St. George’s Hall, Liverpool, has 8000 pipes and upwards of 100 stops; and we imagine that the one at Leeds is still larger. An ingenious method of blowing this last is in use, viz., by hydraulic power—a room underneath being reserved for the water apparatus, which costs comparatively little, and rarely gets out of order. It is the invention of Mr. Joy, of Leeds, and an immense boon to the performer, who can play for any length of time on the full organ without feeling himself dependent on manual labour. The Panopticon organ, built by Hill, and the most complete in London, is worked by steam power, and possesses four manuals, to each of which duplicates are attached, allowing two or three persons to play at once. In the arrangement of notes, however, the Temple organ is the most peculiar, as it contains 14 sounds to the octave, whereas most organs have only 12. The blowing apparatus at Seville is worked by a man walking backwards and forwards over an incline plane balanced in the middle, along which he has to pass ten times before the bellows are filled.

It is useful to know, in cases where funds are deficient or uncertain, that it is by no means necessary to have the instrument complete at once; for, at a small extra expense, spare accommodation can be provided, and spare sliders for stops, which can be filled in at any time.

In many very small churches, the Scudamore organ, containing only one stop, is very handy, and quite powerful enough to lead the congregation,—besides having the merit of being extremely cheap, viz., only 25l. Anything is better than the old barrel-organ, which we are happy to think is rapidly becoming extinct; for no church-music could expect to undergo improvement with such a hopeless piece of machinery,—not to mention the freaks which a barrel of ill-regulated wind would sometimes perform—like the one that started off by itself in the middle of the sermon, and had to be taken out ignominiously into the churchyard and left there to play itself hoarse. We hope that the time will soon come when no parish, however small, will be without its organ, or at least a harmonium, feeling assured that church-music, although not the principal thing in our service, is yet of too much importance to be, as we fear it often is, utterly neglected.

G. P. Bevan.