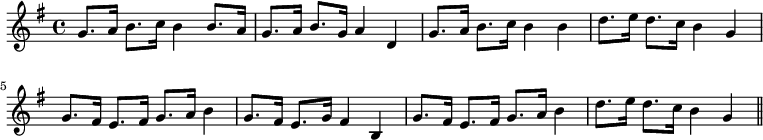

MORRIS, or MORRICE, DANCE. A sort of pageant, accompanied with dancing, probably derived from the Morisco, a Moorish dance formerly popular in Spain and France. Although the name points to this derivation, there is some doubt whether the Morris Dance does not owe its origin to the Matacins. In accounts of the Morisco, no mention is made of any sword-dance, which was a distinguishing feature of the Matacins, and survived in the English Morris Dance (in a somewhat different form) so late as the present century. Jehan Tabourot, in the Orchésographie (Langres, 1588), says that when he was young the Morisco used to be frequently danced by boys who had their faces blacked, and wore bells on their legs. The dance contained much stamping and knocking of heels, and on this account Tabourot says that it was discontinued, as it was found to give the dancers gout. The following is the tune to which it was danced:—

The English Morris Dance is said to have been introduced from Spain by John of Gaunt in the reign of Edward III., but this is extremely doubtful, as there are scarcely any traces of it before the time of Henry VII., when it first began to be popular. Its performance was not confined to any particular time of the year, although it generally formed part of the May games. When this was the case, the characters who took part in it consisted of a Lady of the May, a Fool, a Piper, and two or more dancers. From its association with the May games, the Morris Dance became incorporated with some pageant commemorating Robin Hood, and characters representing that renowned outlaw, Friar Tuck, Little John, and Maid Marian (performed by a boy), are often found taking part in it. A hobby-horse, 4 whifflers, or marshals, a, dragon, and other characters were also frequently added to the above. The dresses of the dancers were ornamented round the ankles, knees, and wrists with different-sized bells, which were distinguished as the fore bells, second bells, treble, mean, tenor, bass, and double bells. In a note to Sir Walter Scott's 'Fair Maid of Perth' there is an interesting account of one of these dresses, which was preserved by the Glover Incorporation of Perth. This dress was ornamented with 250 bells, fastened on pieces of leather in 21 sets of 12, and tuned in regular musical intervals. The Morris Dance attained its greatest popularity in the reign of Henry VIII.; thenceforward it degenerated into a disorderly revel, until, together with the May games and other 'enticements unto naughtiness,' it was suppressed by the Puritans. It was revived at the Restoration, but the pageant seems never to have attained its former popularity, although the dance continued to be an ordinary feature of village entertainments until within the memory of persons now living. In Yorkshire the dancers wore peculiar headdresses made of laths covered with ribbons, and were remarkable for their skill in dancing the sword dance,[1] over two swords placed crosswise on the ground. A country dance which goes by the name of the Morris Dance is still frequently danced in the north of England. It is danced by an indefinite number of couples, standing opposite to one another, as in 'Sir Roger de Coverley.' Each couple holds a ribbon between them, under which the dancers pass in the course of the dance. In Cheshire the following tune is played to the Morris dance,—

but in Yorkshire the tune of an old comic song, 'The Literary Dustman,' is generally used. [App. p.720 "In Yorkshire the following tune, founded on that of 'The Literary Dustman,' is generally used."]

[ W. B. S. ]

MORTIER DE FONTAINE. A pianist of celebrity, born at Warsaw May 13, 1816. He was possessed of unusual technical ability, and is said to have been the first person to play the great sonata of Beethoven op. 106 in public. From 1853 to 1860 he resided in St. Petersburg, since then in Munich, Paris, and many other towns, and is now living in London. [App. p.720 "date of death, May 10, 1883."]

[ J. A. F. M. ]

MOSCHELES, IGNAZ, the foremost pianist after Hummel and before Chopin, was born at Prague on May 30, 1794. His precocious aptitude for music aroused the interest of Dyonis Weber, the director of the Prague Conservatoriuin. Weber brought him up on Mozart and Clementi. At fourteen years of age he played a concerto of his own in public; and soon after, on the death of his father, was sent to Vienna to shift for himself as a pianoforte teacher and player, and to pursue his studies in counterpoint under Albrechtsberger, and in composition under Salieri.

The first volume of 'Aus Moscheles [2]Leben,' extracts from his diary, edited by Mme. Moscheles (Leipzig, 1872), offers bright glimpses of musical life in Vienna during the first decade of the century, and shows how quickly young Moscheles became a favourite in the best musical circles.