In the plainer kind of MSS., written in black ink only, the letters F and C were placed at the beginning of their respective lines, no longer distinguishable by difference of colour; and thus arose our modern F and C Clefs, which, like the G Clef of later date, are really nothing more than conventional modifications of the old Gothic letters, transformed into a kind of technical Hieroglyphic, and passing through an infinity of changes, before arriving at the form now universally recognised.

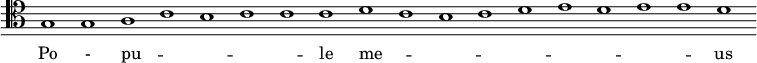

Early in the 10th century, Hucbaldus, a Monk of S. Amand sur l'Elnon, in Flanders,[1] introduced a Stave consisting of a greater number of lines, and therefore more closely resembling, at first sight, our own familiar form, though in reality its principle was farther removed from that than the older system already described. The Lines themselves were left unoccupied. The syllables intended to be sung were written in the Spaces between them; and, in order to shew whether the Voice was to proceed by a Tone, or a Semitone, the letters T and S (for Tonus, and Semitonium) were written at the beginning of each, sometimes alone, but more frequently accompanied by other characters analogous to the signs used in the earlier Greek system, and connected with the machinery of the Tetrachords, which formed a conspicuous feature in Hucbald's teaching.

One great advantage attendant upon this system was, that by increasing the number of lines, it could be applied to a Scale of any extent, and even used for a number of Voices singing at the same time. Hucbaldus himself saw this; and has left us specimens of Discant, written in four different parts, which are easily distinguishable from each other by means of diagonal lines placed between the syllables. [See Organum; Part-writing.]

Not long after the time of Hucbaldus, we find traces of a custom—described by Vincenzo Galilei, in 1581, and afterwards, by Kircher—of leaving the Spaces vacant, and indicating the Notes by Points written upon the Lines only, the actual Degrees of the Scale being determined by Greek Letters placed at the end of the Stave.

The way was now fully prepared for the last great improvement; which, despite its incalculable importance, seems to us absurdly simple. It consisted in drawing two plain black Lines above the red and yellow ones which had preceded the broader Stave of Hucbald whose system soon fell into disuse and writing the Notes on alternate Lines and Spaces. The credit of this famous invention is commonly awarded to Guido d'Arezzo; but, though far from espousing the views of certain critics of the modern destructive school, who would have us believe that that learned Benedictine invented nothing at all, we cannot but admit, that, in this case, his claim is not altogether incontestable. His own words prove that he scrupled not to utilise the inventions of others when they suited his purpose. He may have done so here. We have shewn that both Lines and Spaces were used before his time, though not in combination. But this is not all. In an antient Office-Book—a highly interesting 'Troparium'—once used at Winchester Cathedral, and now preserved in the Bodleian

- ↑ Hence, frequently called 'Monachus Elnonensis.' Ob. 930.