piano, or the degree of force which each of these different actions is calculated to bear. Something is also due to the piano itself. Whilst the Vienna hammer of the time of Beethoven and Hummel (1815–1830) was covered with four or five layers of buckskin of varying thickness, the present hammer is covered with only one piece of felt, and produces a tone which though larger and stronger, is undoubtedly less elastic; the action of the Vienna piano was very simple, and it lacked the escape-movement and many other improvements which enable the present piano, with its almost perfect mechanism, to do a considerable part of the work for the performer. Thus we find that while formerly tone, with its different gradations, touch, the position of the finger, etc., had to be made matters of special study, the present piano with its accomplishments saves this study: whilst formerly the pedal was used but sparingly, it is at present used almost incessantly. Clearness, neatness of execution, a quiet deportment at the instrument, were once deemed to be absolute necessities; it is but seldom that we are gratified at present with these excellent qualities. Whilst in past times the performer treated his instrument as a respected and beloved friend, and almost caressed it, many of our present performers appear to treat it as an enemy, who has to be fought with, and at last conquered. These exaggerated notions cannot last, and their frequent misapplication must in the end become evident to the public; and it is probable that sooner or later a reaction will set in, and the sound principles of our forefathers again be followed.

The enormous progress made by our leading piano-manufacturers, the liberal application of metal in the body of the instrument, and the rich, full, and eminently powerful tone thereby gained, are followed by a serious disadvantage in the effective performance of chamber music. The execution of a piece for the piano, violin and violoncello, in the style which Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven desired and imagined, is now an impossible thing; indeed the equilibrium between the instrument of percussion and the string instruments is now lost. The just rival of the present piano is no longer a single violin or violoncello, but the full orchestra itself. Increased muscular force on the part of the player, exerted on pianos of ten times the ancient tone, is now opposed to the tone of instruments which have undergone no increase of power—indeed the rise in the pitch of the concert piano necessitates at times the use of thinner strings in the violin and violoncello. The much fuller and almost incessant employment of broken chords (arpeggios) in the piano part of sonatas, trios, and other chamber-pieces, is absolutely overwhelming to the string instruments; passages which Mozart and Beethoven introduced in single notes appear now in octaves, which are mostly played so loud as almost to silence the weaker tone of the string instrument; and whilst formerly the thinner tone of the piano allowed an amalgamation of tone-colour, the preponderance of metal in the present instrument precludes it. It would therefore often be most desirable for the pianist to forego some of his undoubted advantages with regard to force, by playing with moderation, by using the pedal with discrimination, and (particularly in rooms of smaller dimensions), by not opening the entire top of the piano. If the above assertions are doubted, a comparison of the last movements of Beethoven's C minor Trio op. 1, and Mendelssohn's C minor Trio, op. 66, will at once show their correctness. If the piano is considered as (what it was to our forefathers) a chamber instrument, we may point to it as the most perfect and satisfactory of all; but when, on the other hand, it is used to substitute the orchestra, it falls in spite of all its prodigious capabilities short of the expected effect. The thoughtful pianist will therefore exercise a just discretion and moderation, and will thus be able to produce a legitimate effect of which neither Mozart nor Beethoven ever dreamt.

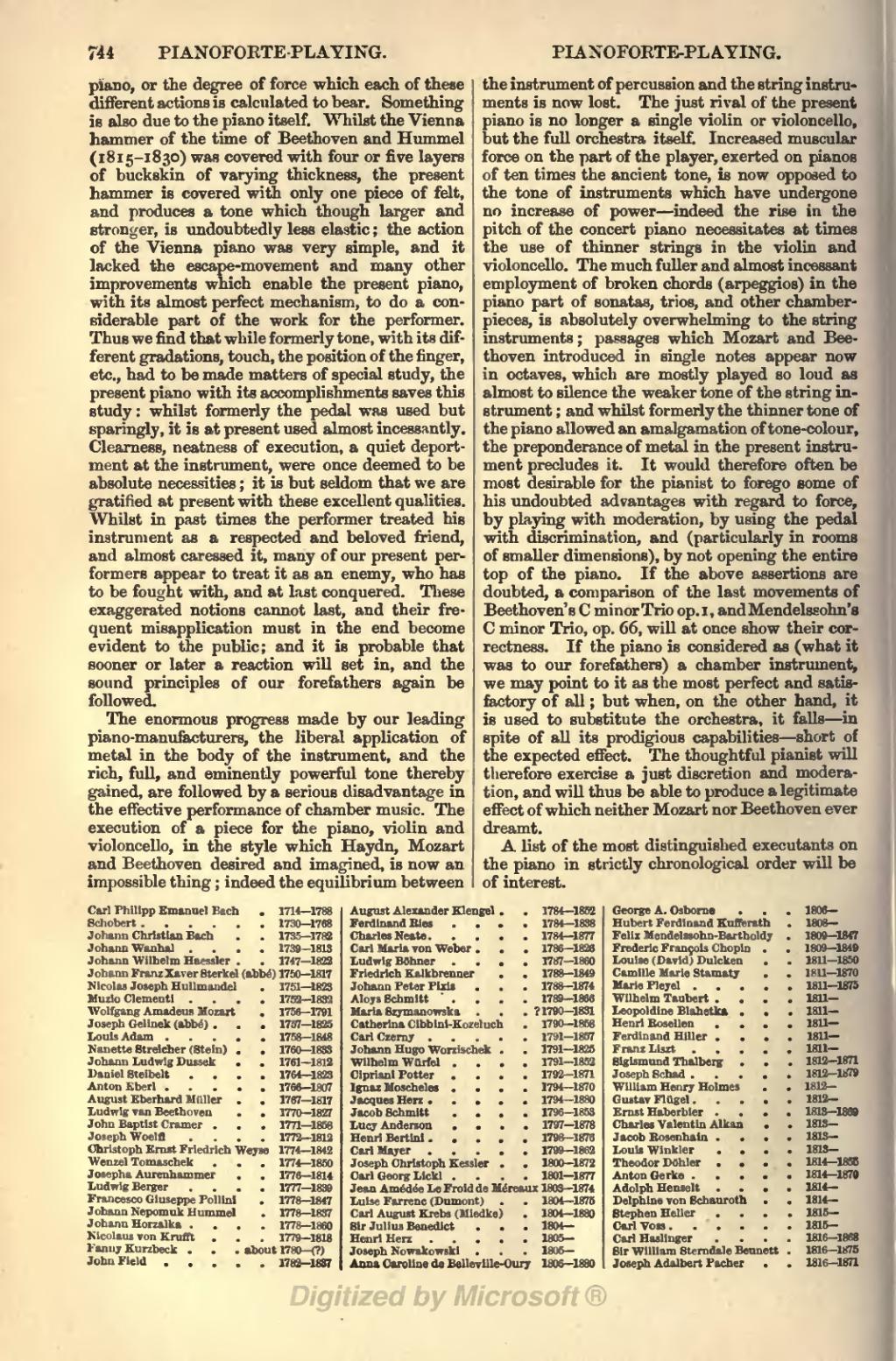

A list of the most distinguished executants on the piano in strictly chronological order will be of interest. [Years in brackets are added from pp.748–9 of the Appendix.]

| Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach | 1714–1788 | |

| Schobert | 1730–[1767] | |

| Johann Christian Bach | 1735–1782 | |

| Johann Wanhal | 1739–1813 | |

| Johann Wilhelm Haessler | 1747–1822 | |

| Johann Franz Xaver Sterkel (abbé) | 1750–1817 | |

| Nicolas Joseph Hullmandel | 1751–1823 | |

| Muzio Clementi | 1752–1832 | |

| Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | 1756–1791 | |

| Joseph Gelinek (abbé) | 1757–1825 | |

| Louis Adam | 1758–1848 | |

| Nanette Streicher (Stein) | [1769]–1833 | |

| Johann Ludwig Dussek | 1761–1812 | |

| Daniel Steibelt | 1764–1823 | |

| Anton Eberl | 1766–1807 | |

| August Eberhard Mailer | 1767–1817 | |

| Ludwig van Beethoven | 1770–1827 | |

| John Baptist Cramer | 1771–1858 | |

| Joseph Woelfl | 1772–1812 | |

| Christoph Ernst Friedrich Weyse | 1774–1842 | |

| Wenzel Tomaschek | 1774–1850 | |

| Josepha Aurenhammer | 1776–1814 | |

| Ludwig Berger | 1777–1839 | |

| Francesco Giuseppe Pollini | 1778–1847 | |

| Johann Nepomuk Hummel | 1778–1837 | |

| Johann Horzalka | 1778–1860 | |

| Nicolaus von Krufft | 1779–1818 | |

| Fanny Kurzbeckabout | 1780–(?) | |

| John Field | 1782–1837 | |

| August Alexander Klengel | 1784–1852 | |

| Ferdinand Ries | 1784–1838 | |

| Charles Neate | 1784–1877 | |

| Carl Maria von Weber | 1786–1826 | |

| Ludwig Böhner | 1787–1860 | |

| Friedrich Kalkbrenner | [1784]–1849 | |

| Johann Peter Pixis | 1788–1874 | |

| Aloys Schmitt | 1789–1866 | |

| Maria Szymanowska | ? | 1790–1831 |

| Catherina Cibbini-Kozeluch | 1790–1858 | |

| Carl Czerny | 1791–1857 | |

| Johann Hugo Worzischek | 1791–1825 | |

| Wilhelm Wörfel | 1791–1852 | |

| Cipriani Potter | 1792–1871 | |

| Ignaz Moscheles | 1794–1870 | |

| Jacques Herz | 1794–1880 | |

| Jacob Schmitt | 1796–1853 | |

| Lucy Anderson | [1790]–1878 | |

| Henri Bertini | 1798–1876 | |

| Carl Mayer | 1799–1862 | |

| Joseph Christoph Kessler | 1800–1872 | |

| Carl Georg Lickl | 1801–1877 | |

| Jean Amédée Le Frold de Méreaux | 1803–1874 | |

| Luise Farrenc (Dumont) | 1804–1875 | |

| Carl August Krebs (Miedke) | 1804–1880 | |

| Sir Julius Benedict | 1804–[1885] | |

| Henri Herz | 1805– | |

| Joseph Nowakowski | 1805– | |

| Anna Caroline de Belleville-Oury | [1808]–1880 | |

| George A. Osborne | 1806– | |

| Hubert Ferdinand Kufferath | 1808–[1882] | |

| Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy | 1809–1847 | |

| Frederic François Chopin | 1809–1849 | |

| Louise (David) Dulcken | 1811–1850 | |

| Camille Marie Stamaty | 1811–1870 | |

| Marie Pleyel | 1811–1875 | |

| Wilhelm Taubert | 1811– | |

| Leopoldine Blahetka | 1811– | |

| Henri Rosellen | 1811– | |

| Ferdinand Hiller | 1811–[1885] | |

| Franz Liszt | 1811–[1886] | |

| Sigismund Thalberg | 1812–1871 | |

| Joseph Schad | 1812–1879 | |

| William Henry Holmes | 1812–[1885] | |

| Gustav Flügel | 1812– | |

| Ernst Haberbier | 1813–1869 | |

| Charles Valentin Alkan | 1813– | |

| Jacob Rosenhain | 1813– | |

| Louis Winkler | 1813– | |

| Theodor Döhler | 1814–[1858] | |

| Anton Gerke | 1814–1870 | |

| Adolph Henselt | 1814– | |

| Delphine von Schauroth | 1814– | |

| Stephen Heller | 1815– | |

| Carl Voss | 1815–[1882] | |

| Carl Haslinger | 1816–1868 | |

| Sir William Sterndale Bennett | 1816–1875 | |

| Joseph Adalbert Pacher | 1816–1871 |