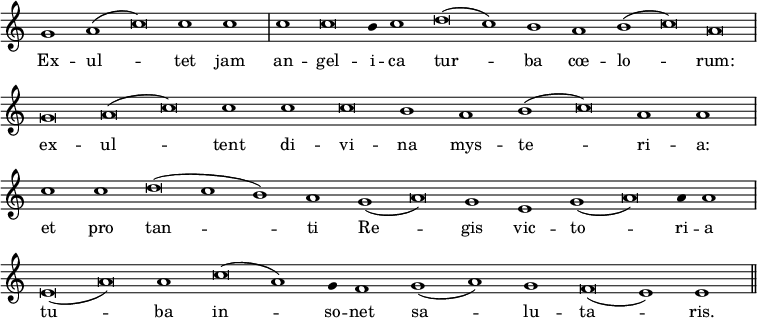

Very different in style from the 'Exultet' is the wailing Chaunt, in the devoutly sad Sixth Mode, to which, in the Pontifical Chapel, the Second and Third Lessons, taken from the Lamentations of Jeremiah, are sung on the three last days in Holy Week. The Chaunt for the Lamentations, which will be found reduced to modern Notation at page 86 of the present volume, stands as much alone as the more jubilant Canticle; but in its own peculiar way. While the one represents the perfection of triumphant dignity, the other carries us down to the very lowest depths of sorrow; and is, indeed, susceptible of such intensely pathetic expression, that none who have ever heard it sung, in the only way in which it can be sung, if it is intended to fulfil its self-evident purpose,—that is to say, with the deepest feeling the Singer can possibly infuse into it,—will feel inclined to deny its title to be regarded as the saddest Melody within the whole range of Music.

Well contrasted with this are the Antiphons and Responsoria for the same sad days—the former far more simple generally, than Antiphons usually are, while the Responsoria are often graced with Perieleses of great beauty.

Upon these, and many minor details, we would willingly have dwelt at greater length; but have now no choice but to proceed, in the last place, to speak of the Hymns included in the Divine Office. The antiquity of these varies greatly, their dates extending over many centuries. Among the oldest are those appointed in the Roman Breviary for the ordinary Sunday and Ferial Offices, and the Lesser Hours. The more antient examples are adapted, for the most part, to simple Melodies, in which Ligatures, even of two notes, are of rare occurrence, a single note being, as a general rule, sung to every syllable. Of these, the well-known inspirations of Prudentius, 'Ales diei nuntius,' 'Lux ecce surgit aurea,' 'Nox et tenebrae,' 'Salvete flores martyrum,' and a few others, date from about the year 400. 'Crudelis Herodes,' and 'A solis ortus cardine,' by Sedulius, were probably written some twenty years later. 'Rector potens, verax Deus,' 'Rerum Deus tenax vigor,' 'Æterne Rex altissime,' and a few others, are also generally referred to the 5th century; 'Audi, benigne Conditor,' and 'Beati nobis gaudia' to the 6th. 'Pange lingua gloriosi,' and 'Vexilla Regis prodeunt,' were written by S. Venantius Fortunatus, about the year 570. 'Te lucis ante terminum,' and 'Iste Confessor' are believed to date from the 7th century; 'Somno refectis artubus' from the 8th; and 'Gloria, laus, et honor,' from the 9th. Of the later Hymns, 'Jesu dulcis memoria' was composed by S. Bernard in 1140; and 'Verbum supernum prodiens' by S. Thomas Aquinas, not earlier than 1260. Hymn-melodies of later date frequently exhibit long Ligatures of great beauty; and, as a rule, the more modern the Hymn, the more elaborate is the Music to which it is adapted; though it does not follow that it is to be preferred, on that account, to the rude but dignified strains peculiar to a more hoary antiquity.

Leaving the student to cultivate a practical acquaintance with the various forms of Plain Song to which we have directed his attention, by referring to the Melodies themselves, as they stand in the Graduale, Vesperale, and Antiphonarium Romanum, it remains only for us to offer a few remarks upon the manner in which this kind of Music may be most effectively performed.

As a matter of course, the Priest's part, in Plain Song Services of any kind, must be sung without any harmonised Accompaniment whatever, care only being taken that the pitch chosen for it may coincide with that necessarily adopted by the Choir, when it is their duty to respond in Polyphonic Harmony. For instance, if the 'Sursum corda,' and 'Preface,' be unskilfully managed in this respect, an awkward break will seriously injure the effect of the 'Sanctus '; while the 'Gloria' and 'Credo' will lose much of their beauty, if equal care be not bestowed upon their respective Intonations. No less judgment is required in the selection of a suitable pitch for the far more difficult 'Exultet,' the first division of which is interupted by a form of 'Sursum corda,' analogous to that which precedes the 'Preface': and, in all cases, a perfect correspondence of intention between Priest and Choir is absolutely indispensable to the success of a Plain Song Service.

The 'Kyrie,' 'Gloria,' 'Credo,' and other movements pertaining to High Mass, may be sung in unison, either by Grave, or Acute Equal Voices, and either with, or without, a fitting Organ Accompaniment. It must, however, be understood that unison, in this case, does not mean octaves. The clauses of the 'Gloria' and 'Credo' produce an excellent effect, when sung by the Voices of Boys and Men alternately: but, when both sing together, all dignity of style is lost in the general thinness of the resulting tone. This remark applies with equal force to the Psalms sung at Lauds and Vespers, and even to the Hymns. In the Pontifical Chapel, the Verses are entrusted either to Sopranos or Altos in unison, or to Tenors and Basses; alternated, on certain occasions, with the noblest and most severe forms of Faux Bourdon—of course unaccompanied. At Notre Dame de Paris, and S. Sulpice, one Verse of a Psalm, or Canticle, is very effectively sung by Tenors and Basses in unison, and one in Faux Bourdon; both with a grand Organ Accompaniment, which, when well managed, by no means destroys the peculiar