minim in the other, and so on. But this method is subject to the serious drawback that it is possible to understand the sign in two opposed senses, according as the first of the two note-values is taken to refer to the new tempo or to that just quitted. On this point composers are by no means agreed, nor are they even always consistent, for Brahms, in his 'Variations on a Theme by Paganini,' uses the same sign in opposite senses, first in passing from Var. 3 to Var. 4, where a ![]() of Var. 4 equals a

of Var. 4 equals a ![]() quarter note of Var. 3 (Ex. 3), and afterwards from Var. 9 to Var. 10, a

quarter note of Var. 3 (Ex. 3), and afterwards from Var. 9 to Var. 10, a ![]() of Var. 10 being equal to a

of Var. 10 being equal to a ![]() of Var. 9 (Ex. 4).

of Var. 9 (Ex. 4).

![{ \new Staff << \mark \markup \small "Ex. 3. Var. 3." \time 6/8 \partial 8

\new Voice \relative e'' { \stemUp

s8 | e16 s8. g,16[ bes] e s8. f,16[ a] | }

\new Voice \relative a' { \stemDown

a16[ c] | s e[ b gis] s8. e'16[ a, fis] } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/j/y/jyhp8tdi09uqyy0i7pmupk36tdv1ssc/jyhp8tdi.png)

![{ \new Staff << \mark \markup \small "Var. 4" \tempo \markup { \concat { ( \smaller \general-align #Y #DOWN \note {4} #1 " = " \smaller \general-align #Y #DOWN \note {8} #1 ) } } \time 12/16

\new Voice \relative e''' { \stemUp

<e c^( e,>8.[\startTrillSpan <e) c>8 dis16]\stopTrillSpan

<e g,^( e>8.[\startTrillSpan <e) b>8 dis16]\stopTrillSpan }

\new Voice \relative a { \stemDown

a16[ a' c c' c, a] g,[ g' b b' b, g] } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/r/dr36yytn147xq1229gkjzhpcapjcm9w/dr36yytn.png)

![{ \relative e' { \mark \markup \small "Var. 10." \tempo \markup { \concat { ( \smaller \general-align #Y #DOWN \note {4} #1 " = " \smaller \general-align #Y #DOWN \note {8} #1 ) } } \time 2/4

r16 <e c>8[ <d b> <c a> <d b>16] ~ |

q16 <e c>8.\noBeam r16 <fis dis cis>8. } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/m/om9nnqhihh9nfookh07yk89f4nxp79h/om9nnqhi.png)

A far safer means of expressing proportion is by a definite verbal direction, a method frequently adopted by Schumann, as for instance in the 'Faust' music, where he says Ein Takt wie vorher zwei—one bar equal to two of the preceding movement; and Um die Hälfte langsamer (by which is to be understood twice as slow, not half as slow again), and so in numerous other instances.

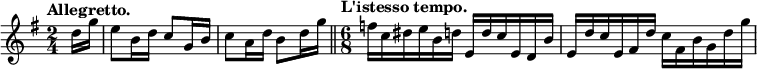

When there is a change of rhythm, as from common to triple time, while the total length of a bar remains unaltered, the words l'istesso tempo, signifying 'the same speed,' are written where the change takes place, as in the following example, where the crotchet of the 2-4 movement is equal to the dotted crotchet of that in 6-8, and so, bar for bar, the tempo is unchanged.

Beethoven, Bagatelle, op. 119, No. 6.

The same words are occasionally used when there is no alteration of rhythm, as a warning against a possible change of speed, as in Var. 3 of Beethoven's Variations, op. 120, and also, though less correctly, when the notes of any given species remain of the same length, while the total value of the bar is changed, as in the following example, where the value of each quaver remains the same, although the bar of the 2-4 movement is only equal to two-thirds of one of the foregoing bars.

Beethoven, Bagatelle, op. 126, No. 1.

![{ \relative b' { \key g \major \time 3/4 \tempo "Andante con moto." \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

<< { b8 a a4 a^( | a4. fis8 b a) } \\

{ g4 f e | f( d) r } >> \bar "||"

\time 2/4 \tempo "L'istesso tempo."

r8 e([ b' a)] | r g([ b a)] } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/7/e/7e0vvg15zlrv3ojmry2l0v01p4ltoit/7e0vvg15.png)

A gradual increase of speed is indicated by the word accelerando or stringendo, a gradual slackening by rallentando or ritardando. All such effects being proportional, every bar and indeed every note should as a rule take its share of the general increase or diminution, except in cases where an accelerando extends over many bars, or even through a whole composition. In such cases the increase of speed is obtained by means of frequent slight but definite changes of tempo (the exact points at which they take place being left to the judgment of performer or conductor) much as though the words più mosso were repeated at intervals throughout. Instances of an extended accelerando occur in Mendelssohn's chorus, 'O! great is the depth,' from 'St. Paul' (26 bars), and in his Fugue in E minor, op. 35, no. 1 (63 bars). On returning to the original tempo after either a gradual or a precise change the words tempo primo are usually employed, or sometimes Tempo del Tema, as in Var. 12 of Mendelssohn's 'Variations Sérieuses.'

The actual speed of a movement in which the composer has given merely one of the usual tempo indications, without any reference to the metronome, depends of course upon the judgment of the executant, assisted in many cases by tradition. But there are one or two considerations which are of material influence in coming to a conclusion on the subject. In the first place, it would appear that the meaning of the various terms has somewhat changed in the course of time, and in opposite directions, the words which express a quick movement now signifying a yet more rapid rate, at least in instrumental music, and those denoting slow tempo a still slower movement, than formerly. There is no absolute proof that this is the case, but a comparison of movements similarly marked, but of different periods, seems to remove all doubt. For instance, the Presto of Beethoven's Sonata, op. 10, no. 3, might be expressed by M.M. ![]() = 144, while the Finale of Bach's Italian Concerto, also marked Presto, could scarcely be played quicker than

= 144, while the Finale of Bach's Italian Concerto, also marked Presto, could scarcely be played quicker than ![]() = 126 without disadvantage. Again, the commencement of Handel's Overture to the 'Messiah' is marked Grave, and is played about

= 126 without disadvantage. Again, the commencement of Handel's Overture to the 'Messiah' is marked Grave, and is played about ![]() = 60, while the Grave of Beethoven's Sonata Pathétique requires a tempo of only

= 60, while the Grave of Beethoven's Sonata Pathétique requires a tempo of only ![]() = 60, exactly twice as slow. The causes of these differences are probably on the one hand the greatly increased powers of execution pos-

= 60, exactly twice as slow. The causes of these differences are probably on the one hand the greatly increased powers of execution pos-