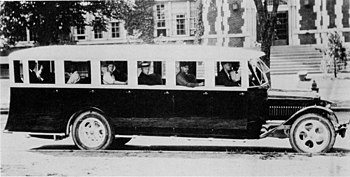

A 1922 deluxe coach manufactured by the Superior Motor Coach Body Company.

During the period from 1921 to 1930, bond proceeds contributed from 25 to 40 percent of all State construction funds. This was the first great period of accelerated bond financing. Illinois, for example, authorized bond issues totaling $160 million; Missouri, $135 million; and North Carolina, $115 million. In these States, and others with similar programs, bond issues formed the bulk of highway construction funds during the decade.

A number of States that did not or, because of constitutional limitations, could not issue bonds did not hesitate to make use of the borrowing power of the counties, townships, and road districts. These units in numerous States either borrowed to build roads that later became State highways or supplied bond proceeds to the State highway departments.

Beginning in the 1920’s, many States undertook to reimburse the counties for these contributions to State highway systems. These obligations usually took one of two forms: (1) An agreement between the State and its local governments whereby the State would reimburse the local governments in annual amounts for costs incurred initially in building roads that later become part of the State systems or (2) an agreement whereby the State would pay to its counties an annual amount equal to the interest and principal on local highway bonds issued for such purposes. The security for this type of obligation was somewhat obscure except when the State had funded or refunded the obligation from the proceeds of its own bond issues.

The practice of transferring funds between levels of government complicates the pattern of highway finance in other ways. The States not only provide financial aid to counties and cities, but they spend money directly on county roads and city streets. There are also arrangements whereby one unit of government performs certain services (maintenance, for example) for another and is reimbursed for the cost of the services.

Most of the Federal expenditures for highways in 1921 were, of course, in the form of aid to the States, amounting to $78 million. The States also received $33 million from county and local rural governments and transferred $22 million to them—a net increase of $11 million in State funds and a corresponding decrease in the county and local funds available for expenditure on roads.

The Federal Highway Act of 1921 confirmed the Federal Government’s policy against tolls on federally aided facilities expressed in the 1916 Act. But large bridges and other crossing facilities, because of their semi-monopoly position and their costliness, had long been widely accepted as suitable for toll-revenue financing. The use of revenue bonds payable solely from the earnings of the facility (tolls) began with the Port of New York Authority bond issues in 1926.

In 1927 Federal policy with respect to tolls was modified by the Oldfield Act (now 23 U.S.C. 129(a)), which allowed the States or their instrumentalities to use Federal funds to construct or acquire toll bridges, provided that net revenues would be applied to the capital costs of the facility or the retirement of its debt and provided that the facility would be toll free upon retirement of its outstanding indebtedness. This Act had the effect of discouraging the construction of privately owned facilities and did not lead to any significant amount of toll bridge construction.

From War to Depression

The period following passage of the Federal Highway Act of 1921 was one of considerable accomplishment, as improvements on the designated Federal-aid system moved forward. Annual Federal authorizations remained at $75 million through 1930 and the onset of the Great Depression.

Total expenditure for highways by all levels of government grew rapidly, reaching $2.5 billion by 1930. State income for highway purposes had risen steadily since 1920. The yield of State motor fuel

244