the scarcity of good roadbuilding stone, which had to be hauled long distances. In Indiana and Illinois the road was only a cleared and graded dirt track.

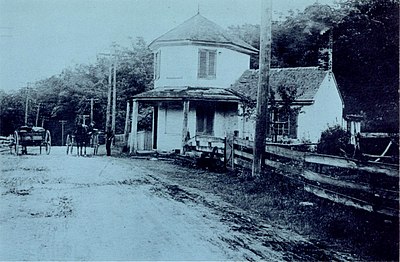

Old tollhouse on Cumberland Road near Frostburg, Md.

The annual appropriation bills continued to be bitterly opposed in Congress and passed by increasingly narrower margins. After 1832 there was sentiment in Congress to use the money appropriated for the National Road to build a railroad west from Columbus, Ohio, and an unsuccessful amendment to the appropriation bill for 1836 proposed to do just that. The last regular appropriation for the Road was in 1838, but construction continued until 1840 when the funds ran out.[1]

By its act of 1831, Ohio accepted the road as fast as it was completed by the Federal engineers and put it under toll. The road was never finished in Indiana and Illinois, and in 1848 Congress ceded to the former “all the rights and privileges of every kind belonging to the United States as connected with said road. . . .” A similar act for Illinois was passed in 1856. In 1879 Congress granted Ohio the right to make the road free, “Provided, That this consent shall have no effect in respect to creating or recognizing any duty or liability whatever on the part of the United States.”[2]

The National Road never reached the Mississippi, but petered out in the Illinois prairies. Its ultimate demise could have been forecast in 1831 when Congress agreed to turn the eastern sections over to the States for operation and maintenance. The end was due not so much to the constitutional and sectional objections that had plagued the road from the beginning, as to the growing feeling in the country and in Congress that roads and canals were already obsolete for long-distance transportation. The day of the railroad was at hand.

The Maysville Turnpike Veto

The course of highway policy in the United States was profoundly influenced by two presidential vetoes. President Monroe’s veto of Federal toll collections on the Cumberland Road has already been mentioned. President Jackson’s veto on May 27, 1830, of turnpike stock subscriptions established national policy with respect to internal improvements of purely local character.

In January 1827, the Kentucky Legislature petitioned Congress to provide Federal aid for an artificial road from Maysville to Lexington, Kentucky. This would be an extension of the mail route leaving the National Road at Zanesville, Ohio, and following Zane’s Trace to the Ohio River. In 1828 an appropriation bill in the U.S. Congress authorizing this road failed by only one vote in the Senate.[3]

The Legislature then incorporated the Maysville, Washington, Paris, and Lexington Turnpike Road Company to build the road, with the provision that 1,500 shares of stock be reserved for subscription by the U.S. Government. In a parallel action, Congress passed a bill authorizing the Secretary of the Treasury to subscribe to 1,500 shares in the Company in the name and for the use of the United States.[4]

22