place is attached to the outer circle like the tail of a Q. Place the three counters or engines marked A, the three marked B, and the three marked C at the places indicated. The puzzle is to move the engines, one at a time, along the lines, from stopping-place to stopping-place, until you succeed in getting an A, a B, and a C on each circle, and also A, B, and C on each straight line. You are required to do this in as few moves as possible. How many moves do you need?

223.—A RAILWAY MUDDLE.

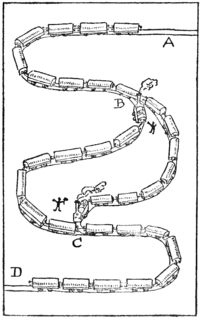

The plan represents a portion of the line of the London, Clodville, and Mudford Railway Company. It is a single line with a loop. There is only room for eight wagons, or seven wagons and an engine, between B and C on either the left line or the right line of the loop. It happened that two goods trains (each consisting of an engine and sixteen wagons) got into the position shown in the illustration. It looked like a hopeless deadlock, and each engine-driver wanted the other to go back to the next station and take off nine wagons. But an ingenious stoker undertook to pass the trains and send them on their respective journeys with their engines properly in front. He also contrived to reverse the engines the fewest times possible. Could you have performed the feat? And how many times would you require to reverse the

engines? A "reversal" means a change of direction, backward or forward. No rope-shunting, fly-shunting, or other trick is allowed. All the work must be done legitimately by the two engines. It is a simple but interesting puzzle if attempted with counters.

224.—THE MOTOR-GARAGE PUZZLE.

The difficulties of the proprietor of a motor garage are converted into a little pastime of a kind that has a peculiar fascination. All you need is to make a simple plan or diagram on a sheet of paper or cardboard and number eight counters, 1 to 8. Then a whole family can enter into an amusing competition to find the best possible solution of the difficulty.

The illustration represents the plan of a motor garage, with accommodation for twelve cars. But the premises are so inconveniently restricted that the proprietor is often caused considerable perplexity. Suppose, for example, that the eight cars numbered 1 to 8 are in the positions shown, how are they to be shifted in the quickest possible way so that 1, 2, 3, and 4 shall change places with 5, 6, 7, and 8—that is, with the numbers still running from left to right, as at present, but the top row exchanged with the bottom row? What are the fewest possible moves?

One car moves at a time, and any distance counts as one move. To prevent misunderstanding, the stopping-places are marked in squares, and only one car can be in a square at the same time.

225.—THE TEN PRISONERS.

If prisons had no other use, they might still be preserved for the special benefit of puzzle-makers. They appear to be an inexhaustible mine of perplexing ideas. Here is a little poser that will perhaps interest the reader for a short period. We have in the illustration a prison of sixteen cells. The locations of the ten prisoners will be seen. The jailer has queer superstitions about odd and even numbers, and he