hundred thousand pounds from the sale of forfeited estates in England and Ireland, &c. The ministers and commanders are asserted to have taken good care of themselves. Cromwell's own income is stated at nearly two million pounds, or one million nine hundred thousand pounds; namely, one million five hundred thousand pounds from England, forty-three thousand pounds from Scotland, and two hundred and eight thousand pounds from Ireland. The members of parliament were paid at the rate of four pounds a week each, or about three hundred thousand pounds a year altogether; and Walker, in his "History of Independency," says that Lenthall, the speaker, held offices to the amount of nearly eight thousand pounds a year; that Bradshaw had Eltham Palace, and an estate of one thousand pounds a year, as bestowed for presiding at the king's trial; and that nearly eight hundred thousand pounds were spent on gifts to adherents of the party. As these statements, however, are those of their adversaries, they no doubt admit of ample abatement; but after all deduction, the demands of king and parliament on the country during the contest, and of the protectorate in keeping down its enemies, must have been enormous. Notwithstanding this, the rate of interest on money continued through this period to decline. During James's reign it was ten per cent.; in 1624, the last year of his reign, it was reduced to eight per cent., and in 1651 was fixed by the parliament at six per cent., at which rate it remained.

Coin of the value of Fifteen Shillings of the Reign of James I.

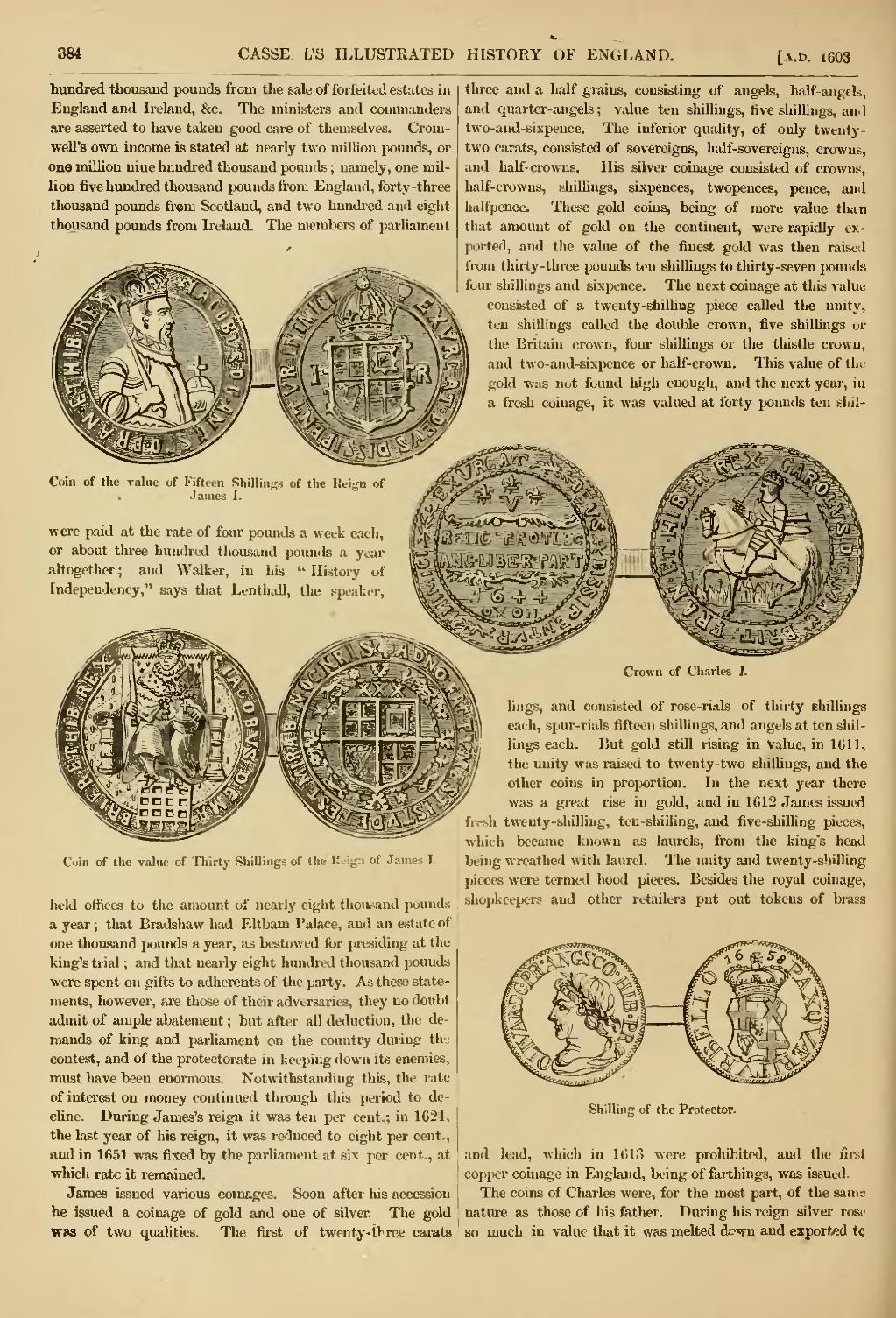

Coin of the value of Thirty Shillings of the Reign of James I.

James issued various coinages. Soon after his accession he issued a coinage of gold and one of silver. The gold was of two qualities. The first of twenty-three carats three and a half grains, consisting of angels, half-angels, and quarter-angels; value ten shillings, five shillings, and two-and-sixpence. The inferior quality, of only twenty-two carats, consisted of sovereigns, half-sovereigns, crowns, and half-crowns. His silver coinage consisted of crowns, half-crowns, shillings, sixpences, twopences, pence, and halfpence. These gold coins, being of more value than that amount of gold on the continent, were rapidly exported, and the value of the finest gold was then raised from thirty-three pounds ten shillings to thirty-seven pounds four shillings and sixpence. The next coinage at this value consisted of a twenty-shilling piece called the unity, ten shillings called the double crown, five shillings or the Britain crown, four shillings or the thistle crown, and two-and-sixpence or half-crown. This value of the gold was not found high enough, and the next year, a fresh coinage, it was valued at forty pounds ten shillings, and consisted of rose-rials of thirty shillings each, spur-rials fifteen shillings, and angels at ten shillings each. But gold still rising in Value, in 1011, the unity was raised to twenty-two shillings, and the other coins in proportion. In the next year there was a great rise in gold, and in 1612 James issued fresh twenty-shilling, ten-shilling, and five-shilling pieces, which became known as laurels, from the king's head being wreathed with laurel. The unity and twenty-shilling pieces were termed hood pieces. Besides the royal coinage, shopkeepers and other retailers put out tokens of brass and lead, which in 1610 were prohibited, and the first copper coinage in England, being of farthings, was issued.

Crown of Charles I.

Shilling of the Protector.

The coins of Charles were, for the most part, of the same nature as those of his father. During his reign silver rose so much in value that it was melted down and exported to