till 1168 that the chief Wendish fortress, at Arkona in Rügen, containing the sanctuary of their god Svantevit, was surrendered, the Wends agreeing to accept Danish suzerainty and the Christian religion at the same time. From Arkona Absalon proceeded by sea to Garz, in south Rügen, the political capital of the Wends, and an all but impregnable stronghold. But the unexpected fall of Arkona had terrified the garrison, which surrendered unconditionally at the first appearance of the Danish ships. Absalon, with only Sweyn, bishop of Aarhus, and twelve “housecarls,” thereupon disembarked, passed between a double row of Wendish warriors, 6000 strong, along the narrow path winding among the morasses, to the gates of the fortress, and, proceeding to the temple of the seven-headed god Rügievit, caused the idol to be hewn down, dragged forth and burnt. The whole population of Garz was then baptized, and Absalon laid the foundations of twelve churches in the isle of Rügen. The destruction of this chief sally-port of the Wendish pirates enabled Absalon considerably to reduce the Danish fleet. But he continued to keep a watchful eye over the Baltic, and in 1170 destroyed another pirate stronghold, farther eastward, at Dievenow on the isle of Wollin. Absalon’s last military exploit was the annihilation, off Strela (Stralsund), on Whit-Sunday 1184, of a Pomeranian fleet which had attacked Denmark’s vassal, Jaromir of Rügen. He was now but fifty-seven, but his strenuous life had aged him, and he was content to resign the command of fleets and armies to younger men, like Duke Valdemar, afterwards Valdemar II., and to confine himself to the administration of the empire which his genius had created. In this sphere Absalon proved himself equally great. The aim of his policy was to free Denmark from the German yoke. It was contrary to his advice and warnings that Valdemar I. rendered fealty to the emperor Frederick Barbarossa at Dôle in 1162; and when, on the accession of Canute V. in 1182, an imperial ambassador arrived at Roskilde to receive the homage of the new king, Absalon resolutely withstood him. “Return to the emperor,” cried he, “and tell him that the king of Denmark will in no wise show him obedience or do him homage.” As the archpastor of Denmark Absalon also rendered his country inestimable services, building churches and monasteries, introducing the religious orders, founding schools and doing his utmost to promote civilization and enlightenment. It was he who held the first Danish Synod at Lund in 1167. In 1178 he became archbishop of Lund, but very unwillingly, only the threat of excommunication from the holy see finally inducing him to accept the pallium. Absalon died on the 21st of March 1201, at the family monastery of Sorö, which he himself had richly embellished and endowed.

Absalon remains one of the most striking and picturesque figures of the Middle Ages, and was equally great as churchman, statesman and warrior. That he enjoyed warfare there can be no doubt; and his splendid physique and early training had well fitted him for martial exercises. He was the best rider in the army and the best swimmer in the fleet. Yet he was not like the ordinary fighting bishops of the Middle Ages, whose sole concession to their sacred calling was to avoid the “shedding of blood” by using a mace in battle instead of a sword. Absalon never neglected his ecclesiastical duties, and even his wars were of the nature of crusades. Moreover, all his martial energy notwithstanding, his personality must have been singularly winning; for it is said of him that he left behind not a single enemy, all his opponents having long since been converted by him into friends.

See Saxo, Gesta Danorum, ed. Holder (Strassburg, 1886), books x.-xvi.; Steinstrup, Danmark’s Riges Historie. Oldtiden og den ældre Middelalder, pp. 570-735 (Copenhagen, 1897–1905). (R. N. B.)

ABSCESS (from Lat. abscedere, to separate), in pathology, a collection of pus among the tissues of the body, the result of bacterial inflammation. Without the presence of septic organisms abscess does not occur. At any rate, every acute abscess contains septic germs, and these may have reached the inflamed area by direct infection, or may have been carried thither by the blood-stream. Previous to the formation of abscess something has occurred to lower the vitality of the affected tissue—some gross injury, perchance, or it may be that the power of resistance against bacillary invasion was lowered by reason of constitutional weakness. As the result, then, of lowered vitality, a certain area becomes congested and effusion takes place into the tissues. This effusion coagulates and a hard, brawny mass is formed which softens towards the centre. If nothing is done the softened area increases in size, the skin over it becomes thinned, loses its vitality (mortifies) and a small “slough” is formed. When the slough gives way the pus escapes and, tension being relieved, pain ceases. A local necrosis or death of tissue takes place at that part of the inflammatory swelling farthest from the healthy circulation. When the attack of septic inflammation is very acute, death of the tissue occurs en masse, as in the core of a boil or carbuncle. Sometimes, however, no such mass of dead tissue is to be observed, and all that escapes when the skin is lanced or gives way is the creamy pus. In the latter case the tissue has broken down in a molecular form. After the escape of the core or slough along with a certain amount of pus, a space, the abscess-cavity, is left, the walls of which are lined with new vascular tissue which has itself escaped destruction. This lowly organized material is called granulation tissue, and exactly resembles the growth which covers the floor of an ulcer. These granulations eventually fill the contracting cavity and obliterate it by forming interstitial scar-tissue. This is called healing by second intention. Pus may accumulate in a normal cavity, such as a joint or bursa, or in the cranial, thoracic or abdominal cavity. In all these situations, if the diagnosis is clear, the principle of treatment is evacuation and drainage. When evacuating an abscess it is often advisable to scrape away the lining of unhealthy granulations and to wash out the cavity with an antiseptic lotion. If the after-drainage of the cavity is thorough the formation of pus ceases and the watery discharge from the abscess wall subsides. As the cavity contracts the discharge becomes less, until at last the drainage tube can be removed and the external wound allowed to heal. The large collections of pus which form in connexion with disease of the spinal column in the cervical, dorsal and lumbar regions are now treated by free evacuation of the tuberculous pus, with careful antiseptic measures. The opening should be in as dependent a position as possible in order that the drainage may be thorough. If tension recurs after opening has been made, as by the blocking of the tube, or by its imperfect position, or by its being too short, there is likely to be a fresh formation of pus, and without delay the whole procedure must be gone through again.

(E. O.*)

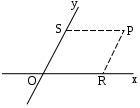

ABSCISSA (from the Lat. abscissus, cut off), in the Cartesian system of co-ordinates, the distance of a point from the axis of y measured parallel to the horizontal axis (axis of x). Thus PS (or OR) is the abscissa of P. The word appears for the first time in a Latin work written by Stefano degli Angeli (1623–1697), a professor of mathematics in Rome. (See Geometry, § Analytical.)

ABSCISSION (from Lat. abscindere), a tearing away, or cutting

off; a term used sometimes in prosody for the elision of

a vowel before another, and in surgery especially for abscission

of the cornea, or the removal of that portion of the eyeball

situated in front of the attachments of the recti muscles; in

botany, the separation of spores by elimination of the connexion.

ABSCOND (Lat. abscondere, to hide, put away), to depart in a secret manner; in law, to remove from the jurisdiction of the courts or so to conceal oneself as to avoid their jurisdiction. A person may “abscond” either for the purpose of avoiding arrest for a crime (see Arrest), or for a fraudulent purpose, such as the defrauding of his creditors (see Bankruptcy).

ABSENCE (Lat. absentia), the fact of being “away,” either in body or mind; “absence of mind” being a condition in which the mind is withdrawn from what is passing. The special occasion roll-call at Eton College is called “Absence,” which the boys attend in their tall hats. A soldier must get permission or “leave of absence” before he can be away from his regiment. Seven years’ absence with no sign of life either by letter or