fervour, aided by persecution, drove them farther and farther away from the abodes of men into mountain solitudes or lonely deserts. The deserts of Egypt swarmed with the “cells” or huts of these anchorites. Anthony, who had retired to the Egyptian Thebaid during the persecution of Maximin, A.D. 312, was the most celebrated among them for his austerities, his sanctity, and his power as an exorcist. His fame collected round him a host of followers, emulous of his sanctity. The deeper he withdrew into the wilderness, the more numerous his disciples became. They refused to be separated from him, and built their cells round that of their spiritual father. Thus arose the first monastic community, consisting of anchorites living each in his own little dwelling, united together under one superior. Anthony, as Neander remarks (Church History, vol. iii. p. 316, Clark’s trans.), “without any conscious design of his own, had become the founder of a new mode of living in common, Coenobitism.” By degrees order was introduced in the groups of huts. They were arranged in lines like the tents in an encampment, or the houses in a street. From this arrangement these lines of single cells came to be known as Laurae, Λαὒραι, “streets” or “lanes.”

The real founder of coenobian (κοινός, common, and βίος, life) monasteries in the modern sense was Pachomius, an Egyptian of the beginning of the 4th century. The first community established by him was at Tabennae, an island of the Nile in Upper Egypt. Eight others were founded in his lifetime, numbering 3000 monks. Within fifty years from his death his societies could reckon 50,000 members. These coenobia resembled villages, peopled by a hard-working religious community, all of one sex. The buildings were detached, small and of the humblest character. Each cell or hut, according to Sozomen (H.E. iii. 14), contained three monks. They took their chief meal in a common refectory at 3 p.m., up to which hour they usually fasted. They ate in silence, with hoods so drawn over their faces that they could see nothing but what was on the table before them. The monks spent all the time, not devoted to religious services or study, in manual labour. Palladius, who visited the Egyptian monasteries about the close of the 4th century, found among the 300 members of the coenobium of Panopolis, under the Pachomian rule, 15 tailors, 7 smiths, 4 carpenters, 12 camel-drivers and 15 tanners. Each separate community had its own oeconomus or steward, who was subject to a chief oeconomus stationed at the head establishment. All the produce of the monks’ labour was committed to him, and by him shipped to Alexandria. The money raised by the sale was expended in the purchase of stores for the support of the communities, and what was over was devoted to charity. Twice in the year the superiors of the several coenobia met at the chief monastery, under the presidency of an archimandrite (“the chief of the fold,” from μάνδρα, a fold), and at the last meeting gave in reports of their administration for the year. The coenobia of Syria belonged to the Pachomian institution. We learn many details concerning those in the vicinity of Antioch from Chrysostom’s writings. The monks lived in separate huts, καλύβια, forming a religious hamlet on the mountain side. They were subject to an abbot, and observed a common rule. (They had no refectory, but ate their common meal, of bread and water only, when the day’s labour was over, reclining on strewn grass, sometimes out of doors.) Four times in the day they joined in prayers and psalms.

The necessity for defence from hostile attacks, economy of space and convenience of access from one part of the community to another, by degrees dictated a more compact and orderly arrangement of the buildings of a monastic coenobium. Large piles of building were erected, with strong outside walls, capable of resisting the assaults of an enemy, within which all the Santa Laura, Mount Athos.necessary edifices were ranged round one or more open courts, usually surrounded with cloisters. The usual Eastern arrangement is exemplified in the plan of the convent of Santa Laura, Mount Athos (Laura, the designation of a monastery generally, being converted into a female saint).

This monastery, like the oriental monasteries generally, is surrounded by a strong and lofty blank stone wall, enclosing an area of between 3 and 4 acres. The longer side extends to a length of about 500 feet. There is only one main entrance, on the north side (A), defended by three separate iron doors. Near the entrance is a large tower (M), a constant feature in the monasteries of the Levant. There is a small postern gate at L. The enceinte comprises two large open courts, surrounded with buildings connected with cloister galleries of wood or stone. The outer court, which is much the larger, contains the granaries and storehouses (K), and the kitchen (H) and other offices connected with the refectory (G). Immediately adjacent to the gateway is a two-storied guest-house, opening from a cloister (C). The inner court is surrounded by a cloister (EE), from which open the monks’ cells (II). In the centre of this court stands the catholicon or conventual church, a square building with an apse of the cruciform domical Byzantine type, approached by a domed narthex. In front of the church stands a marble fountain (F), covered by a dome supported on columns. Opening from the western side of the cloister, but actually standing in the outer court, is the refectory (G), a large cruciform building, about 100 feet each way, decorated within with frescoes of saints. At the upper end is a semicircular recess, recalling the triclinium of the Lateran Palace at Rome, in which is placed the seat of the hegumenos or abbot. This apartment is chiefly used as a hall of meeting, the oriental monks usually taking their meals in their separate cells.

St Laura is exceeded in magnitude by the convent of Vatopede, also on Mount Athos. This enormous establishment covers at least 4 acres of ground, and contains so many separate buildings within its massive walls that it resembles a fortified town. It lodges above 300 monks, and the establishment of the hegumenos is described as resemblingVatopede. the court of a petty sovereign prince. The immense refectory, of the same cruciform shape as that of St Laura, will accommodate 500 guests at its 24 marble tables.

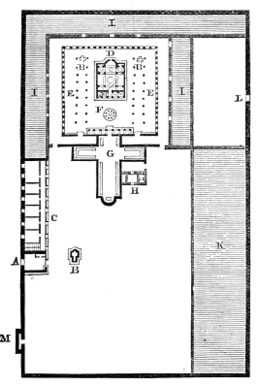

The annexed plan of a Coptic monastery, from Lenoir, shows a church of three aisles, with cellular apses, and two ranges of cells on either side of an oblong gallery.

Monasticism in the West owes its extension and development to Benedict of Nursia (born A.D. 480). His rule was diffused with miraculous rapidity from the parent foundation on Monte Cassino through the whole of western Europe, and every country witnessed the erection of monasteries far exceeding anything that had yet been seen in spaciousness and splendour. Few great towns in Italy were without their Benedictine convent, and they quickly rose in all the great centres of population in England, France and Spain. The number of these monasteries founded between A.D. 520 and 700 is