In the year 1786 the prince of Wales, afterwards George IV., began to erect the pavilion at Brighton, and this led to a great increase of traffic, so that in 1820 no less than 70 coaches daily visited and left Brighton. The number continued to increase, until in 1835 there were as many as 700 mail coaches throughout Great Britain and Ireland. The system of road construction introduced by Mr McAdam during this time was of great value in facilitating this development.

Notwithstanding the competition of the sedan-chair (q.v.), the hackney-coach held its place and grew in importance, till it was supplanted about 1820 by the cabriolet de place, now shortened into “cab” (q.v.), which had previously held a most important place in Paris. In that city the cabriolet came into great public favour about the middle of the 18th century, and in the year 1813 there were 1150 such vehicles plying in the Parisian streets. The original cabriolet was a kind of hooded gig, inside which the driver sat, besides whom there was only room left for a single passenger. For hackney purposes Mr Boulnois introduced a four-wheeled cab to carry two persons, which was followed by one to carry four persons, introduced by Mr Harvey, the prototype of the London “four-wheeler.”

The hansom patent safety cab (1834) owes its invention to J. A. Hansom (q.v.), the architect of the Birmingham town-hall. This has passed through many stages of improvement with which the name of Forder of Wolverhampton is conspicuously associated.

The prototype of the modern “omnibus” first began plying in the streets of Paris on the 18th of March 1662, going at fixed hours, at a stated fare of five sous. Soldiers, lackeys, pages and livery servants were forbidden to enter such conveyances, which were announced to be pour la plus grande commodité et liberté des personnes de mérite. In the time of Charles X. the omnibus system in reality was established; for no exclusion of any class or condition of person who tendered the proper fare was permitted in the vehicles then put on various routes, and the fact of the carriages being thus “at the service of all” gave rise to the present name. The first London omnibus was started in July 1829 by the enterprising Mr Shillibeer. The first omnibuses were drawn by three horses abreast and carried twenty-two passengers, all inside. Though appearing unwieldy they were light of draught and travelled speedily. They were, however, too large for the convenience of street traffic, and were superseded by others carrying twelve passengers inside. In 1849 an outside seat along the centre of the roof was added. The London General Omnibus Company was founded in 1856; since then continual improvements in this system of public conveyance have been introduced.

Modern Private Carriages.—At the accession of Queen Victoria the means of travelling by road and horse-power, in the case of public coaches, had reached in England its utmost limits of speed and convenience, and the travelling-carriages of the nobility and the wealthy were equipped with the completest and most elaborate contrivances to secure personal comfort and safety. More particularly was this the case as regards continental tours, which had become indispensable to all who had at their command the means for this costly educational and pleasurable experience. Concurrently with this development the style and character of court equipages had also reached a consummate degree of splendour and artistic excellence. Not only was this the case in points of decoration, in which livery colour and heraldic devices were effectively employed, but also in the beauty of outline and skilful structural adaptation, in which respect carriages of that period made greater demands upon the capacity of the builder and the skill of the workman than do those of the present day. For this attainment the art of coachmaking was indebted to a very few leading men, whose genius has left its impress upon the art, and is still jealously cherished by those who in early life had experience of their achievements. The early portion of Queen Victoria’s reign was an age of much emulation; the best-equipped carriages of that period, distinctive of noble families and foreign embassies, with their graceful outline and superb appointments, and harnessed to a splendid breed of horses—all harmoniously blended, perfect in symmetry and adaptation—gave to the London season, more especially on drawing-room days, and at other times in Hyde Park, an attractiveness unequalled in any other capital. After the death of the prince consort, the pageantry of that period very much declined and, except as an appendage of royalty, full-dress carriages have since been comparatively few, though there are hopes of a revival in this direction. Meanwhile, owing to the rapid development of railways and the wide extension of commerce, the demand for carriages greatly increased. The larger types gave place to others of a lighter build and more general utility, in which in some cases an infusion of American ideas made its appearance. In accordance with the universal rule of supply meeting the demand, Mr Stenson, an ironmaster of Northampton, was successful in producing a mild forging steel, which proved for some years, until the manufacture ceased, very conducive to the object of securing lightness with strength. In the early ’seventies the eminent mechanician, Sir Joseph Whitworth, in the course of his scientific studies in the perfecting of artillery, succeeded in manufacturing a steel of great purity, perfectly homogeneous and possessing marvellous tenacity and strength, known as “fluid compressed steel.” Incidentally carriage-building was able to participate in the results of this discovery. Two firms well known to Sir Joseph were asked to test its merits as a material applicable to this industry. In this test much difficulty was experienced, the nature of the steel not being favourable to welding, of which so much is required in the making of coach ironwork; but after much perseverance by skilful hands this was at length accomplished, and for some years there existed not a little rivalry in the use of this material, more especially in the case of carriages on the C and under-spring principle, which for lightness, elegance and luxurious riding left nothing to be desired. Many of these carriages may be referred to to-day as rare examples of constructive skill. Unfortunately, the original cost of the material, still more of the labour to be expended upon it, and the difficulty of educating men into the art of working it, were effectual barriers to its general adoption. The idea, however, had taken hold, and attention was given by other firms to the manufacture of the steel now in general use, admitting of easier application, with approximate, if not equal, results.

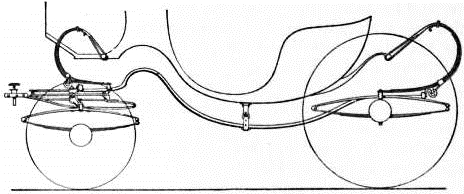

From C and under-spring carriages there arose another application of springs which was very prominently before the public during this period, by means of which it was professed that two drawbacks recognized in the C and under-spring carriages were obviated, which were caused by the perch or bar which passes under the body holding the front and hind parts in rigid connexion, and yet making use of a form of spring to which the same terms may be applied. These objections are the weight of the perch, and the limitation which it causes to the facility of turning, which in narrow roads and crowded thoroughfares is an inconvenience. The objection to weight is, however, minimized by the introduction of steel, and as the more advanced builders almost always construct the perch with a forked arch in front, allowing the wheels to pass under, the difficulty of a limited lock is in a great measure overcome (fig. 1). It must be noted, however (and this cannot be too emphatically stated), that the so-called C springs above referred to are not at all the same in action as the C spring proper; they are but an elongation of the ordinary elliptic spring in the form of the letter C (fig. 2), without adding anything to, but rather lessening their elasticity, and entirely ignoring the principle of suspension