with designs in low relief, picked out with scrolls and arabesques in white enamel or bold floral sprays in leaf-gold. Lustre is frequently found applied to the rich cobalt-blue ground, and there are still existing a few magnificent vases which show the artistic possibilities of this scheme of decoration. It should be noted that when the pieces are in the round, the pattern is usually painted in lustre and not reserved in a lustre ground as on the flat tiles. In the later examples the tin-enamel was replaced entirely by white slip, and the lustre decoration continued in use until the end of the reign of Shah Abbas I. (1587–1629). To the last period belong many charming bowls, narghilis, cups and dishes in a brown lustre, with ruby reflets, on a white or a deep blue ground; this ware is pure white in substance and generally translucent, and the pieces are occasionally signed (see Persian porcelain above).

|

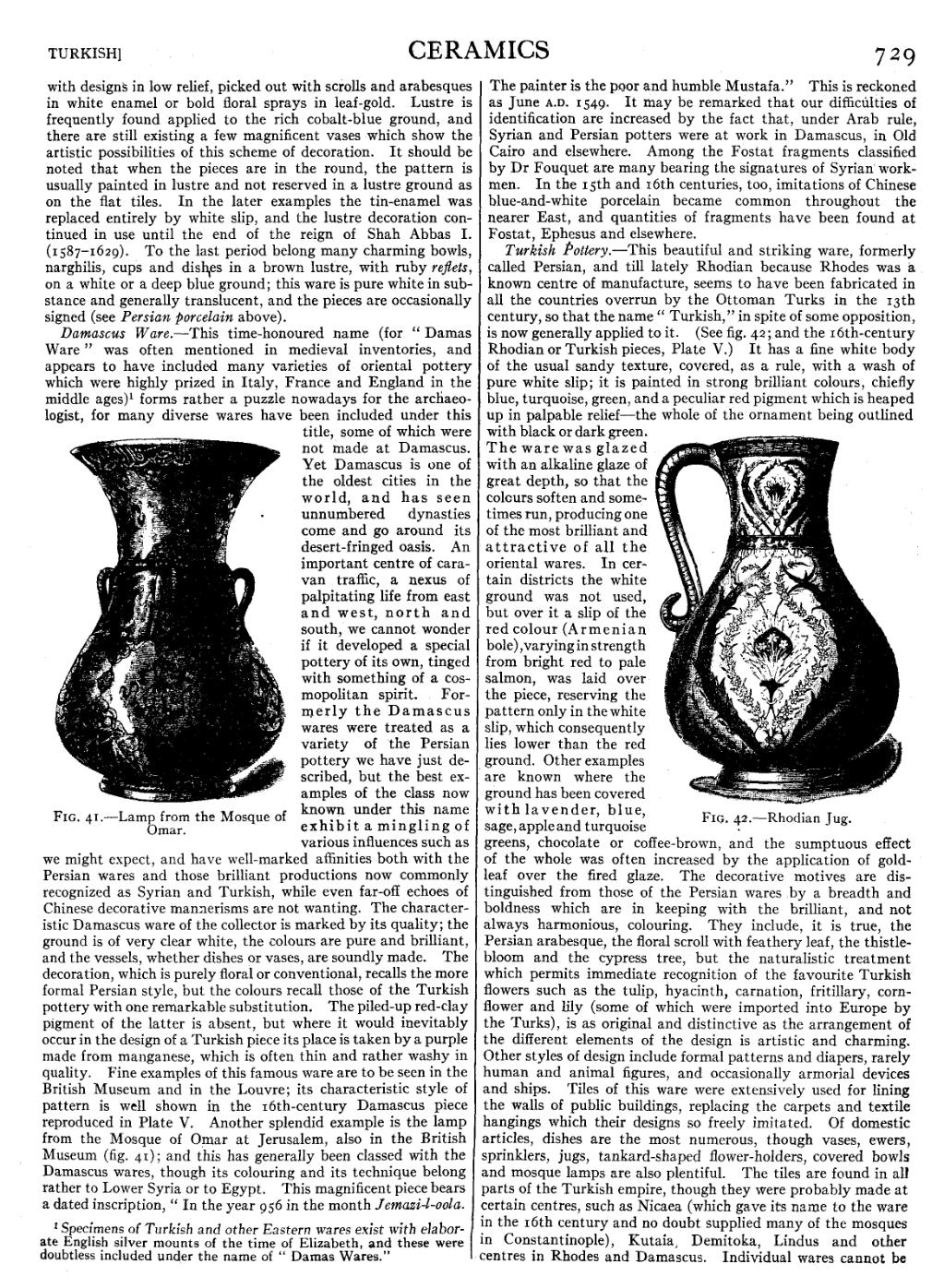

| Fig. 41.—Lamp from the Mosque of Omar. |

Damascus Ware.—This time-honoured name (for “Damas Ware” was often mentioned in medieval inventories, and appears to have included many varieties of oriental pottery which were highly prized in Italy, France and England in the middle ages)[1] forms rather a puzzle nowadays for the archaeologist, for many diverse wares have been included under this title, some of which were not made at Damascus. Yet Damascus is one of the oldest cities in the world, and has seen unnumbered dynasties come and go around its desert-fringed oasis. An important centre of caravan traffic, a nexus of palpitating life from east and west, north and south, we cannot wonder if it developed a special pottery of its own, tinged with something of a cosmopolitan spirit. Formerly the Damascus wares were treated as a variety of the Persian pottery we have just described, but the best examples of the class now known under this name exhibit a mingling of various influences such as we might expect, and have well-marked affinities both with the Persian wares and those brilliant productions now commonly recognized as Syrian and Turkish, while even far-off echoes of Chinese decorative mannerisms are not wanting. The characteristic Damascus ware of the collector is marked by its quality; the ground is of very clear white, the colours are pure and brilliant, and the vessels, whether dishes or vases, are soundly made. The decoration, which is purely floral or conventional, recalls the more formal Persian style, but the colours recall those of the Turkish pottery with one remarkable substitution. The piled-up red-clay pigment of the latter is absent, but where it would inevitably occur in the design of a Turkish piece its place is taken by a purple made from manganese, which is often thin and rather washy in quality. Fine examples of this famous ware are to be seen in the British Museum and in the Louvre; its characteristic style of pattern is well shown in the 16th-century Damascus piece reproduced in Plate V. Another splendid example is the lamp from the Mosque of Omar at Jerusalem, also in the British Museum (fig. 41); and this has generally been classed with the Damascus wares, though its colouring and its technique belong rather to Lower Syria or to Egypt. This magnificent piece bears a dated inscription, “In the year 956 in the month Jemazi-l-oola. The painter is the poor and humble Mustafa.” This is reckoned as June A.D. 1549. It may be remarked that our difficulties of identification are increased by the fact that, under Arab rule, Syrian and Persian potters were at work in Damascus, in Old Cairo and elsewhere. Among the Fostat fragments classified by Dr Fouquet are many bearing the signatures of Syrian workmen. In the 15th and 16th centuries, too, imitations of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain became common throughout the nearer East, and quantities of fragments have been found at Fostat, Ephesus and elsewhere.

|

| Fig. 42.—Rhodian Jug. |

Turkish Pottery.—This beautiful and striking ware, formerly called Persian, and till lately Rhodian because Rhodes was a known centre of manufacture, seems to have been fabricated in all the countries overrun by the Ottoman Turks in the 13th century, so that the name “Turkish,” in spite of some opposition, is now generally applied to it. (See fig. 42; and the 16th-century Rhodian or Turkish pieces, Plate V.) It has a fine white body of the usual sandy texture, covered, as a rule, with a wash of pure white slip; it is painted in strong brilliant colours, chiefly blue, turquoise, green, and a peculiar red pigment which is heaped up in palpable relief—the whole of the ornament being outlined with black or dark green. The ware was glazed with an alkaline glaze of great depth, so that the colours soften and sometimes run, producing one of the most brilliant and attractive of all the oriental wares. In certain districts the white ground was not used, but over it a slip of the red colour (Armenian bole), varying in strength from bright red to pale salmon, was laid over the piece, reserving the pattern only in the white slip, which consequently lies lower than the red ground. Other examples are known where the ground has been covered with lavender, blue, sage, apple and turquoise greens, chocolate or coffee-brown, and the sumptuous effect of the whole was often increased by the application of gold-leaf over the fired glaze. The decorative motives are distinguished from those of the Persian wares by a breadth and boldness which are in keeping with the brilliant, and not always harmonious, colouring. They include, it is true, the Persian arabesque, the floral scroll with feathery leaf, the thistle-bloom and the cypress tree, but the naturalistic treatment which permits immediate recognition of the favourite Turkish flowers such as the tulip, hyacinth, carnation, fritillary, cornflower and lily (some of which were imported into Europe by the Turks), is as original and distinctive as the arrangement of the different elements of the design is artistic and charming. Other styles of design include formal patterns and diapers, rarely human and animal figures, and occasionally armorial devices and ships. Tiles of this ware were extensively used for lining the walls of public buildings, replacing the carpets and textile hangings which their designs so freely imitated. Of domestic articles, dishes are the most numerous, though vases, ewers, sprinklers, jugs, tankard-shaped flower-holders, covered bowls and mosque lamps are also plentiful. The tiles are found in all parts of the Turkish empire, though they were probably made at certain centres, such as Nicaea (which gave its name to the ware in the 16th century and no doubt supplied many of the mosques in Constantinople), Kutaia, Demitoka, Lindus and other centres in Rhodes and Damascus. Individual wares cannot be

- ↑ Specimens of Turkish and other Eastern wares exist with elaborate English silver mounts of the time of Elizabeth, and these were doubtless included under the name of “Damas Wares.”