Persian style often appear on the Cafaggiolo wares (see example, Plate VI). Not a little can be learnt from the ornament on the reverse sides of the dishes and plates; those of Faenza and Siena are richly decorated with scale patterns and concentric bands; those of Cafaggiolo and Venice are either left blank or have one or two rings of yellow. A few pre-eminently beautiful dishes, with central figure subjects of miniature-like finish in delicate landscapes with poplar trees in a peculiar mannered style, are probably the work of M. Benedetto of Siena. Borders of arabesques with black or deep orange ground belong to the same factory and were perhaps decorated by the same hand. The dishes covered, except for a few small medallions, with interlaced oak branches (“a cerquate” decoration), are no doubt the productions of Castel Durante; and a certain class of large dishes with figure subjects in blue on a toned blue glaze, and sometimes with formal ornaments in relief, are of undisputed Venetian origin.

|

Later Cafaggiolo |

Another phase of majolica decoration began about the middle of the 16th century and synchronized with the decline of the pictorial style. The figure subjects were relegated to central panels or entirely replaced by small medallions, and the rest of the surface covered with fantastic figures among floral scrolls, inspired by Raphael’s grotesques painted on the walls of the Loggie in the Vatican. The prevailing tone of this ornament was yellow or orange, and the tin-enamel ground, which is always more or less impure in colour on Italian pottery, was washed over with a pure milk-white, known as bianco di Ferrara or bianco allatato, said to have been invented by Alphonso I., duke of Ferrara, who took an active interest in his private factory founded at Ferrara, and managed by potters from Faenza and Urbino.

| |

Turin |

Savona Potter’s marks. |

The new style flourished at Urbino, Pesaro and Ferrara; at the first-named particularly in the workshops of the Patanazzi family, and lasted far into the 17th century. But the majolica was now in full decline, partly through the falling off of princely patronage, and partly, perhaps, owing to a reaction in favour of Chinese porcelain, which was becoming more plentiful and better known in Europe. The manufacture, however, never entirely ceased, and revivals of the old style were attempted at the end of the 17th century by Ferdinando Maria Campori of Siena, who copied Raphael’s and Michelangelo’s compositions, and by the families of Gentile and Grue at Naples and Castelli. The majolica of Castelli is distinguished by the lightness of the ware, good technique, and harmonious but pale and rather weak colouring; it continued into the 18th century. A coarse and inferior ware was made at Padua and Monte Lupo; and the factories of Faenza were still active, producing, among other kinds, a pure white ware with moulded scallops and gadroons. The industry continued to flourish in Venice and the north. Black ware with gilt decoration was a Venetian product of the 17th century, and at Savona and Genoa blue painted ware in imitation of Chinese blue and white porcelain made its appearance. In the 18th century a new departure was made in the introduction of enamel painting over the glaze, a method borrowed from porcelain; but this process was common to all the faience factories of Europe at the time, and though it was widely practised in Italy no special distinction was attained in any particular factory. In our own days imitations of the 16th century wares continue to be made in the factories of Ginori, Cantigalli and others, not excepting the lustred majolica of Gubbio and Deruta; but, compared with the old pieces, the modern copies are heavy to handle, stiff in drawing, suspiciously wanting in the quality of the colours and the purity of the final glaze which distinguish the work of the best period.

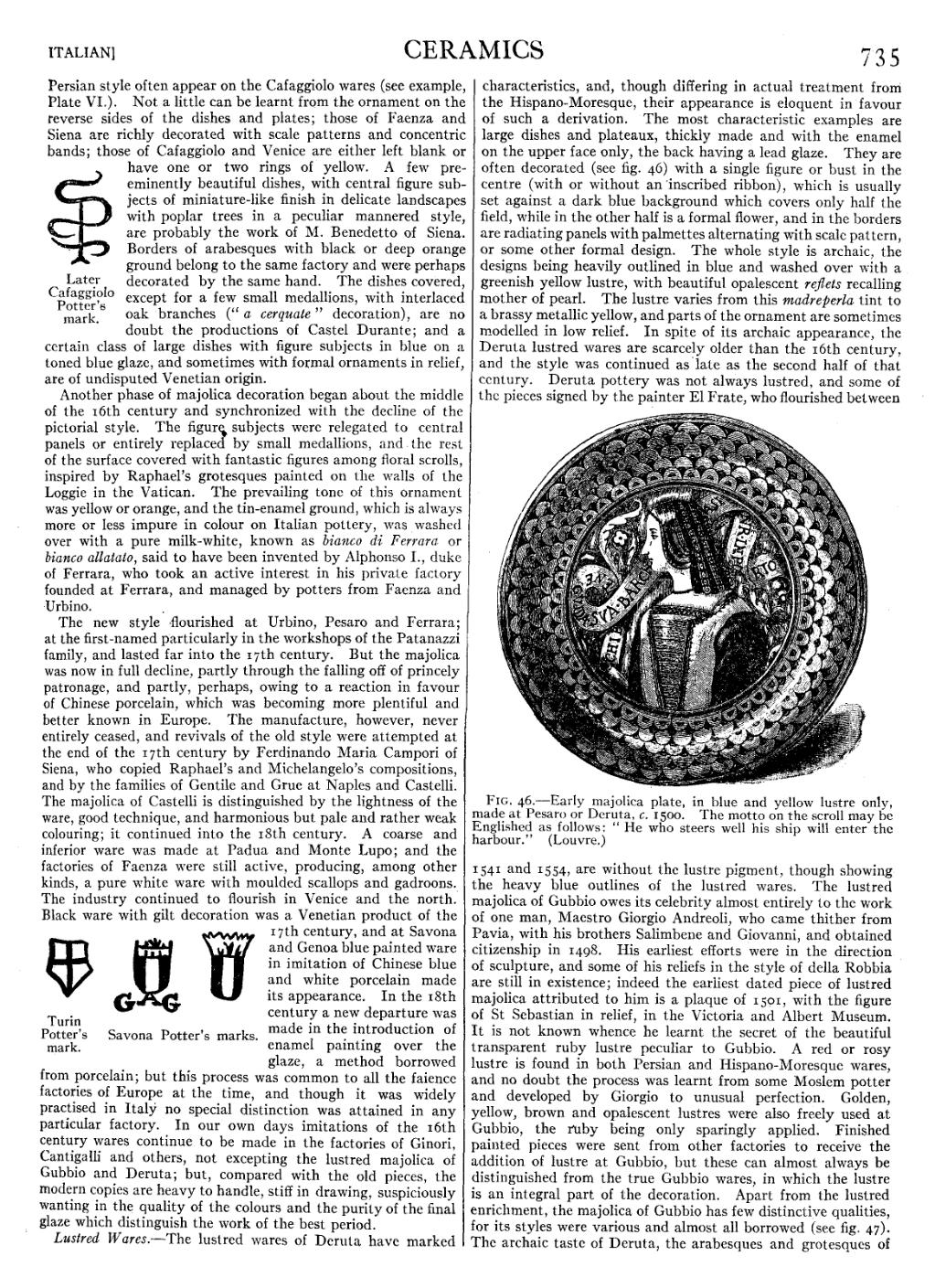

Lustred Wares.—The lustred wares of Deruta have marked characteristics, and, though differing in actual treatment from the Hispano-Moresque, their appearance is eloquent in favour of such a derivation. The most characteristic examples are large dishes and plateaux, thickly made and with the enamel on the upper face only, the back having a lead glaze. They are often decorated (see fig. 46) with a single figure or bust in the centre (with or without an inscribed ribbon), which is usually set against a dark blue background which covers only half the field, while in the other half is a formal flower, and in the borders are radiating panels with palmettes alternating with scale pattern, or some other formal design. The whole style is archaic, the designs being heavily outlined in blue and washed over with a greenish yellow lustre, with beautiful opalescent reflets recalling mother of pearl. The lustre varies from this madreperla tint to a brassy metallic yellow, and parts of the ornament are sometimes modelled in low relief. In spite of its archaic appearance, the Deruta lustred wares are scarcely older than the 16th century, and the style was continued as late as the second half of that century. Deruta pottery was not always lustred, and some of the pieces signed by the painter El Frate, who flourished between 1541 and 1554, are without the lustre pigment, though showing the heavy blue outlines of the lustred wares. The lustred majolica of Gubbio owes its celebrity almost entirely to the work of one man, Maestro Giorgio Andreoli, who came thither from Pavia, with his brothers Salimbene and Giovanni, and obtained citizenship in 1498. His earliest efforts were in the direction of sculpture, and some of his reliefs in the style of della Robbia are still in existence; indeed the earliest dated piece of lustred majolica attributed to him is a plaque of 1501, with the figure of St Sebastian in relief, in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It is not known whence he learnt the secret of the beautiful transparent ruby lustre peculiar to Gubbio. A red or rosy lustre is found in both Persian and Hispano-Moresque wares, and no doubt the process was learnt from some Moslem potter and developed by Giorgio to unusual perfection. Golden, yellow, brown and opalescent lustres were also freely used at Gubbio, the ruby being only sparingly applied. Finished painted pieces were sent from other factories to receive the addition of lustre at Gubbio, but these can almost always be distinguished from the true Gubbio wares, in which the lustre is an integral part of the decoration. Apart from the lustred enrichment, the majolica of Gubbio has few distinctive qualities, for its styles were various and almost all borrowed (see fig. 47). The archaic taste of Deruta, the arabesques and grotesques of