reduced as at G, it is called a bonnet de prêtre. Such works were

rarely used.)

H. Hornwork: Much used for gates, &c.

I.Crown-work.

K. Crowned hornwork.

L. M. New forms of tenaille: (N.B.—These are the forms which

ultimately retained the name.)

N. New form of work called a demi-lune lunettée, the ravelin N

being protected by two counterguards, O.

P. Re-entering places of arms.

Q. Traverses.

R. Salient places of arms.

S. Places of arms without traverses.

T. Orillon, to protect the flank V.

X. A double bastion or cavalier.

Y. A retrenchment with a ditch, of the breach Z.

&. Traverses to protect the terreplein of the ramparts from

enfilade.

Turning back now to the middle of the 16th century we find in the early examples of the use of the bastion that there is no attempt made to defend its faces by flanking fire, the curtains being considered the only weak points of the enceinte. Accordingly, the flanks are arranged at right angles to the curtain, and the prolongation of the faces sometimes falls near the middle of it. When it was found that the faces needed protection, the first attempts to give it were made by erecting cavaliers, or raised parapets, behind the parapet of the curtain or in the bastions.

|

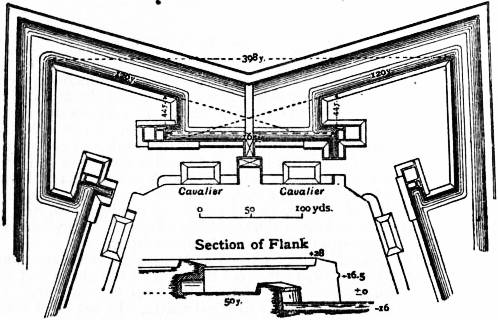

| Fig. 21. |

The first example of the complete bastioned system is found in Paciotto’s citadel of Antwerp, built in 1568 (fig. 21). Here we have faces, flanks and curtain in due proportion; the faces long enough to contain a powerful battery, and the flanks able to defend both curtain and faces. The weak points of this trace, due to its being arranged on a small pentagon, are that the terreplein or interior space of the bastions is rather cramped, and the salient angles too acute.

In the systems published by Speckle of Strassburg in 1589 we find a distinct advance. Speckle’s actual constructions in fortification are of no great importance; but he was a great traveller and observer, and in his work, published The 16th century. just before his death, he has evidently assimilated, and to some extent improved, the best ideas that had been put forward up to that time.

Two specimens from Speckle’s work are well worth studying as connecting links between the 16th and 17th centuries.

Fig. 22 is early 16th-century work much improved. There are no outworks, except the covered way, now fully developed, with a battery in the re-entering place of arms. The bastions are large, but the faces directed on the curtain get little protection from the flanks. To make up for this they are flanked by the large cavaliers in the middle of the curtain. The careful arrangement of the flank should be noted; part of it is retired, with two tiers of fire, some of which is arranged to bear on the face of the bastion. The great saliency of the bastion is a weak point, but the whole arrangement is simple and strong.

|

| Fig 22. |

In the second example, known as Speckle’s “reinforced trace” (fig. 23), we find him anticipating the work of the next century. The ravelin is here introduced, and made so large that its faces are in prolongation of those of the bastions. Speckle’s other favourite ideas are here: the cavaliers and double parapets and his own particular invention of the low batteries behind the re-entering place of arms and the gorge of the ravelin. These low batteries did not find favour with other writers, being liable to be too easily destroyed by the besiegers’ batteries crowning the salients of the covered way.

Speckle’s book is of great importance as embodying the best work of the period. His own ideas are large and simple, but rather in advance of the powers of the artillery of his day.

At the beginning of the 17th century we find the Italian engineers following Paciotto in developing the complete bastioned trace; but they got on to a bad line of thought in trying to reduce everything to symmetry and system. The era of geometrical The 17th century. fortification (or, as Sir George Clarke has called it, “drawing-board” fortification) had already begun with Marchi, and his followers busied themselves entirely in finding geometrical solutions for the application of symmetrical bastioned fronts to such imaginary forms of perimeter as the oval, club, heart, figure of eight, &c. Marchi, however, was one of the first to think of prolonging the resistance of a place by means of outworks such as the ravelin. De Villenoisy says that Busca was the first to discuss the proportions and functions of all the component parts of a front; and Floriani, about 1630, was the last of the important Italians. The characteristics of a good deal of Spanish fortification carried out at this time were, according to the same authority, that the works were well adapted to sites, and the masonry excellent but too much exposed, while the bastions were too small. The Dutch and German schools will be referred to later.

|

| Fig. 23.—Speckle’s Reinforced Trace. |

The French engineers now began to take the lead in adapting the principles already established to actual sites. In the first half of the century the names of de Ville and Pagan stand out as having contributed valuable studies to the advancement of the science. In putting forward their designs they discussed very fully such practical questions as the length of the line of defence, whether this should be governed by the range of artillery or musketry fire, the length of flanks, the use in them of orillons, casemates and retired flanks, the size of bastions, &c.

It is the latter half of the 17th century, however, which is one