of leaf when fully developed (4 to 9 ins. in length and 2 to 312 in breadth) has made them in demand because of the heavy yields. From the variety Bohea, or from hybrids of descent from it, came the China teas of former days and the earlier plantings in India grown from imported China stock. The

Fig. 1.—Bohea variety.

leaves of this variety are generally, roughly speaking, about half the size of those of the Assam Indigenous and Manipur sorts. The bush is in every way smaller than the Assam types. The latter is a tree attaining in its natural conditions, or where allowed to grow unpruned in a seed garden, a height of from 30 to 40 ft. and prospering in the midst of dense moist jungle and in shady sheltered situations.

The Bohea variety is hardy, and capable of thriving under many different conditions of climate and situation, while the indigenous plant is tender and difficult of cultivation, requiring for its success a close, hot, moist and equable climate. In minute structure it presents highly characteristic appearances.

The under side of the young leaf is densely covered with fine one-celled thick-walled hairs, about 1 mm. in length and ·015 mm. in thickness. These hairs entirely disappear with increasing age. The structure of the epidermis of the under side of the leaf, with its contorted cells, is represented in fig. 3.

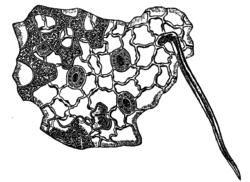

A further characteristic feature of the cellular structure of the tea-leaf is the abundance, especially in grown leaves, of large, branching, thick-walled, smooth cells (idioblasts), which, although they occur in other leaves, are not found in such as are likely to be confounded with or substituted for tea. The minute structure of the leaf in section is illustrated in fig. 4.

Constant controversy has existed as to what is the actual original home of the tea-plant, and probably no one has given to the subject more careful study . than Professor Andreas Krassnow, of Kharkoff University. By order of the Russian government, he visited each of the great tea-growing countries,

Fig. 2.—Bohea Tea-Leaf,full size.

and the results of his observations were published in a book entitled On the Tea-producing Districts of Asia. He holds the opinion that the tea-plant is indigenous, not to Assam only, but to the whole monsoon region of eastern Asia, where he found it growing wild as far north as the islands of southern Japan. He considers that the tea-plant had, from the remotest times, two distinct varieties, the Assam and Chinese, as he thinks that the period of known cultivation has been too short to produce the differences that exist between them.

Fig. 3.—Epidermis of Tea-leaf (under side).

Chemistry.—What may be termed the chemistry of production, viz., that relating to soils, manures, manufacturing processes, &c., has of recent years received great attention from the scientific experts appointed in India and Ceylon to assist and guide the tea planters. The chemistry of the completed teas of commerce does not appear to have been subjected to adequate scientific study. There cannot be said to be any standard or recognized analysis. Many such have been made, and they may be found in chemical text-books of high authority, but they are defective because of the lack of commercial knowledge in association with the chemical skill. More attention seems to have been given to the matter in the United States of America and in Germany and Russia than in England, but the infinite variety of samples known to the commercial expert, and the impossibility of standardizing those in such a manner as to make readily recognizable what the chemist has treated, renders most of the recorded analyses of uncertain value. There seems to be no relationship between the commercial value and the analysis, the arbitrary personal methods of the expert tea-taster being controlled by factors that chemistry does not appear to deal with. One reason may be that analyses are generally made of tea liquors produced by distilled water, which is the very worst possible from the point of view of the commercial expert or in domestic usage.

The principal chemical constituents of tea of practical interest are: caffeine, tannin and essential oil, on which depend respectively the physiological effects, the strength and the flavour. The commercial value appears to depend on the essential oil and aroma, not on the amount of caffeine, tannin or extract.

Fig. 4.—Section through Tea-leaf.

The following is suggested as a typical analysis of an average sample of black tea:—

| Per cent | |

| Albuminous matters | 24 |

| Gummy Matters | 4 |

| Cellulose | 20 |

| Chlorophyll and wax | 2 |

| Caffeine | 3 |

| Tannin | 10 |

| Essential oil | 0·75 |

| Resin | 3 |

| Mineral matter (ash) | 6 |

| Moisture | 7 |

| Extractive matter | 20·25 |

| 100 |

Also a trace (·1 to ·2 per cent.) of boheic acid, a vegetable acid peculiar to tea. The amount of tannin found in green teas appears to be