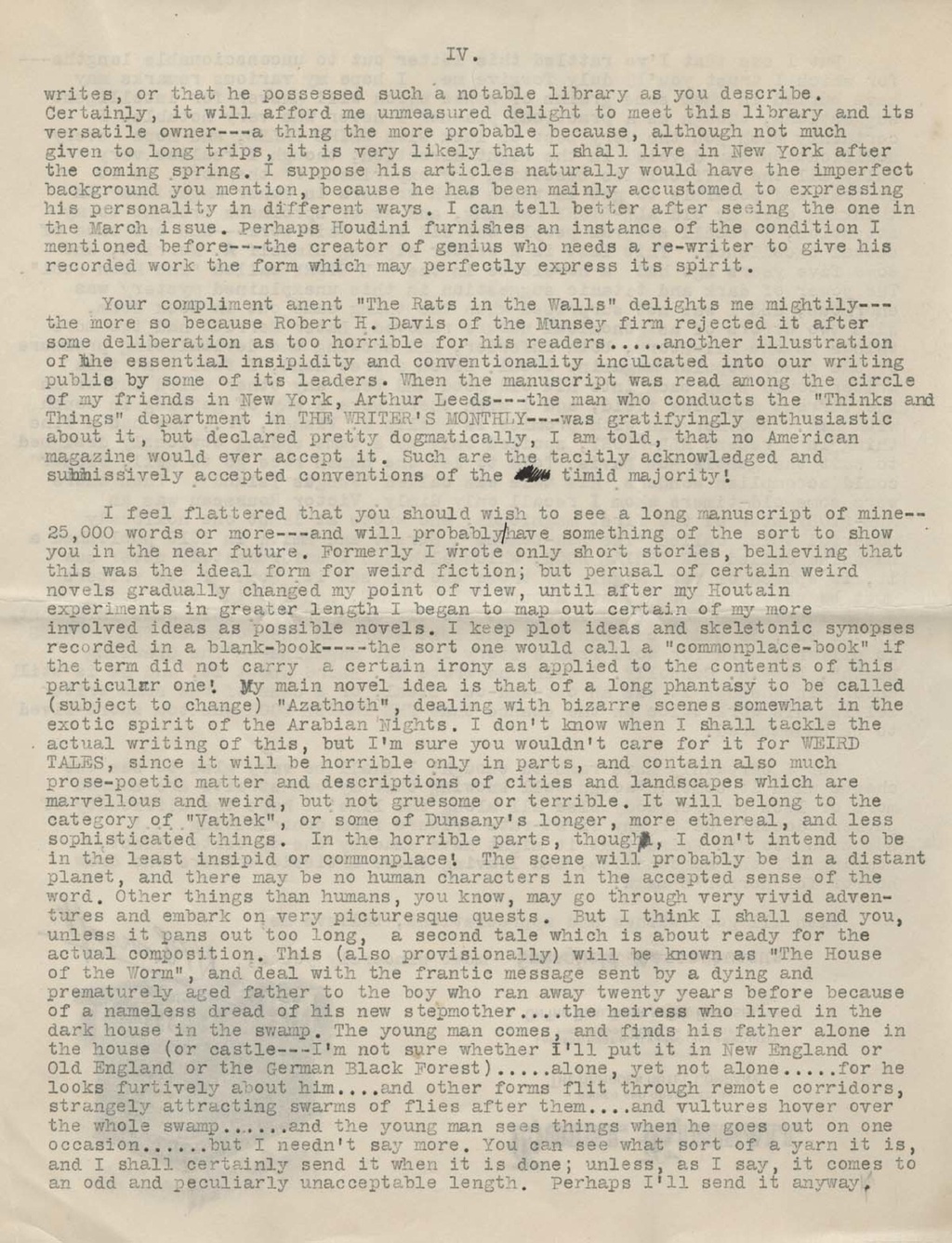

IV.

writes, or that he possessed such a notable library as you describe. Certainly, it will afford me unmeasured delight to meet this library and its versatile owner—a thing the more probable because, although not much given to long trips, it is very likely that I shall live in New York after the coming spring. I suppose his articles naturally would have the imperfect background you mention, because he has been mainly accustomed to expressing his personality in different ways. I can tell better after seeing the one in the March issue, perhaps Houdini furnishes an instance of the condition I mentioned before—the creator of genius who needs a re-writer to give his recorded work the form which may perfectly express its spirit.

Your compliment anent "The Rats in the Walls" delights me mightily—the more so because Robert H. Davis of the Munsey firm rejected it after some deliberation as too horrible for his readers … another illustration of the essential insipidity and conventionality inculcated into our writing public by some of its leaders. When the manuscript was read among the circle of my friends in New York, Arthur Leeds—the man who conducts the "Thinks and Things" department in THE WRITER'S MONTHLY—was gratifyingly enthusiastic about it, but declared pretty dogmatically, I am told, that no American magazine would ever accept it. Such are the tacitly acknowledged and submissively accepted conventions of the timid majority!

I feel flattered that you should wish to see a long manuscript of mine—25,000 words or more—and will probably have something of the sort to show you in the near future. Formerly I wrote only short stories, believing that this was the ideal form for weird fiction; but perusal of certain weird novels gradually changed my point of view, until after my Houtain experiments in greater length I began to map out certain of my more involved ideas as possible novels. I keep plot ideas and skeletonic synopses recorded in a blank-book—the sort one would call a "commonplace-book" if the term did not carry a certain irony as applied to the contents of this particular one! My main novel idea is that of a long phantasy to be called (subject to change) "Azathoth", dealing with bizarre scenes somewhat in the exotic spirit of the Arabian Nights. I don't know when I shall tackle the actual writing of this, but I'm sure you wouldn't care for it for WEIRD TALES, since it will be horrible only in parts, and contain also much prose-poetic matter and descriptions of cities and landscapes which are marvellous and weird, but not gruesome or terrible. It will belong to the category of "Vathek", or some of Dunsany's longer, more ethereal, and less sophisticated things. In the horrible parts, though, I don't intend to be in the least insipid or commonplace! The scene will probably be in a distant planet, and there may be no human characters in the accepted sense of the word. Other things than humans, you know, may go through very vivid adventures and embark on very picturesque quests. But I think I shall send you, unless it pans out too long, a second tale which is about ready for the actual composition. This (also provisionally) will be known as "The House of the Worm", and deal with the frantic message sent by a dying and prematurely aged father to the boy who ran away twenty years before because of a nameless dread of his new stepmother … the heiress who lived in the dark house in the swamp. The young man comes, and finds his father alone in the house (or castle—I'm not sure whether I'll put it in New England or Old England or the German Black Forest) … alone, yet not alone … for he looks furtively about him … and other forms flit through remote corridors, strangely attracting swarms of flies after them … and vultures hover over the whole swamp … and the young man sees things when he goes out on one occasion … but I needn't say more. You can see what sort of a yarn it is, and I shall certainly send it when it is done; unless, as I say, it comes to an odd and peculiarly unacceptable length, perhaps I'll send it anyway.