IT was the first real day of spring; a living, heartsome day. The great sun looked down joyously on an awaking earth; the air had a freshness as of the sea; from every hedgerow the birds piped out; the hills were alive, the valleys jubilant; far away my lord, the mountain, stretched himself lazily in the sunshine; everywhere beneath the glad sky ran a riot of life, the earth thrilled with it, the wind came throbbing with its mad fervor.

In the valley which lies between Emo and Rhamus hill, the turf-cutters were out; and now, the clang of the one o'clock bell in Louth farm-yard having died away among the hills, sat squatted round their fires among the heather. All the morning, from a score of mounds, the blue smoke had streamed up, had run its tattered skirts together above the level of the hilltops, swept before the stress of the wind out over Thrasna River, and gone trailing for the shining roofs of Buun. All the morning it had filled the valley and lain stretched like a blue veil upon the distant hills; wherever you went, all the morning, the pungent smell of it (bringing to you memories of mud walls, soot-blackened rafters, and clacking groups round cottage hearthstones) had come to you, now thin and faint (like the whiff from a peasant's coat as he slouches up the aisle o' Sundays), now gratefully wholesome and refreshing as the breath of whins, now hot and reeking as from the mouths of wattled chimneys. All the morning, in all your wanderings, the wind had brought to you the sound of laughter, the shouts of the men, the songs of the women, the skirls of the children; now and then, as the smoke lifted, you had glimpse of the crowd of workers, seen the flash of the spades and the glint of the shawls and handkerchiefs, the sudden popping of the peat from black bog-holes, the going and coming across the banks of the shrieking barrows; so, all the morning, it had been; now silence held the valley, the smoke went up thin and clear, and, scattered among the willow clumps, you had sight of the turf-cutters gathered in groups round the twinkling fires.

At the top of the bog, not far from the Curleck road, burned the fire of the Dalys; and round it, sitting squat on the dry peat bank, was a party of ten: three men, three women, and four little Dalys—a family group gathered from neighboring bog-holes to make merry over the potatoes and salt.

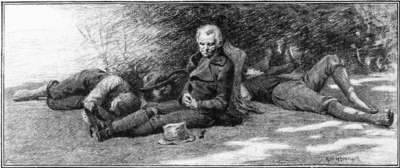

As lord of the fire, and tenant, moreover, of an elegant madhouse (the same, in fact, that, in the old days, had sheltered Pete Coyne), James Daly held chief seat at the feast, well shielded from the wind by a willow clump, his back to a stump, his legs crossed luxuriously. Beside him, on the one hand, his brother-in-law, Mike Brady, a thin, sour-looking man, sat propped against a creel; on the other, his old father sat bent forward like over-ripe corn, his eyes fixed wearily on the fire and