The first named difficulties were entirely overcome by mounting the apparatus on a massive stone floating on mercury; and the second by increasing, by repeated reflection, the path of the light to about ten times its former value.

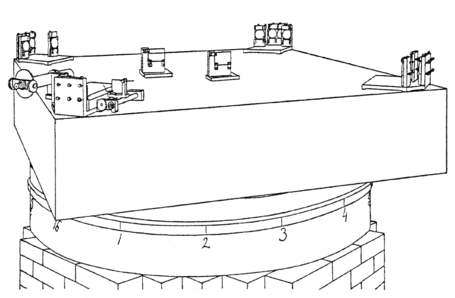

The apparatus is represented in perspective in fig. 3, in plan in fig. 4, and in vertical section in fig. 6. The stone a (fig. 5) is about 1.5 meter square and 0.3 meter thick. It rests on an annular wooden float bb, 1.5 meter outside diameter, 0.7 meter inside diameter, and 0.25 meter thick. The float rests on mercury contained in the cast-iron trough cc, 1.6 centimeter thick, and of such dimensions as to leave a clearance of about one centimeter around the float. A pin d, guided by arms gggg, fits into a socket e attached to the float. The pin may be pushed into the socket or be withdrawn, by a lever pivoted at f. This pin keeps the float concentric with the trough, but does not bear any part of the weight of the stone. The annular iron trough rests on a bed of cement on a low brick pier built in the form of a hollow octagon.

At each corner of the stone were placed four mirrors dd ee fig. 1. Near the center of the stone was a plane-parallel glass b. These were so disposed that light from an argand burner a, passing through a lens, fell on b so as to be in part reflected to d,; the two pencils followed the paths indicated in the figure, bdedbf and bd/e/d/bf respectively, and were observed by the telescope f. Both f and a revolved with the stone. The mirrors were of speculum metal carefully worked to optically plane surfaces five centimeters in diameter, and the glasses b and e were plane-parallel and of the same thickness. 1.25 centimeter;