which he had lived during that earlier time, and to which his steps from the school had then habitually led. We all of us have a definite routine manner of performing certain daily offices connected with the toilet, with the opening and shutting of familiar cupboards, and the like. Our lower centers know the order of these movements, and show their knowledge by their "surprise" if the objects are altered so as to oblige the movement to be made in a different way. But our higher thought-centers know hardly anything about the matter. Few men can tell off-hand which sock, shoe, or trousers-leg they put on first. They must first mentally rehearse the action; and even that is often insufficient—the action must be performed. So of the questions, Which valve of my double door opens first? Which way does my door swing? etc. I can not tell the answer; yet my hand never makes a mistake. No one can describe the order in which he brushes his hair or teeth; yet it is likely that the order is a pretty fixed one in all of us.

These results may be expressed as follows:

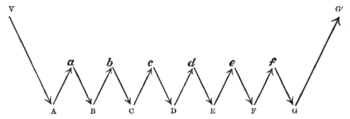

In actions become habitual, what instigates each new muscular contraction to take place in its appointed order is not a thought or a perception, but the sensation occasioned by the muscular contraction just finished. A strictly voluntary action has to be guided by idea, perception, and volition, throughout its course. In a secondarily automatic or habitual action, mere sensation is a sufficient guide, and the upper regions of brain and mind are set comparatively free. A diagram will make the matter clear:

Let A, B, C, D, E, F, G represent an habitual chain of muscular contractions, and let a, b, c, d, e, f, g stand for the respective sensations which these contractions excite in us when they are successively performed. Such sensations will usually be in the muscles, skin, or joints of the parts moved, but they may also be effects of the movement upon the eye or ear. Through them, and through them alone, we are made aware whether the contraction has or has not occurred. When the series, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, is being learned, each of these sensations becomes the object of a separate perception by the mind. By it we test each movement, to see if it be right before advancing to the next. We hesitate, compare, choose, revoke, reject, etc., by intellectual means; and the order by which the next movement is dis-