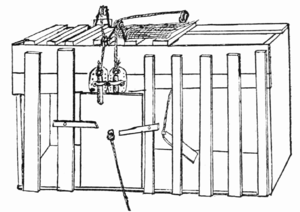

in play some simple mechanism which opened the door. A piece of fish or meat outside the inclosure furnished the motive for their attempts to escape. The inclosures for the cats were wooden boxes, in shape and appearance like the one pictured in Fig. 1, and were about 20 X 15 X 12 inches in size. The boxes for the dogs (who were rather small, weighing on the average about thirty pounds) were about 40 X 22 X 22. By means of such experiments we put animals in situations seeming almost sure to call forth any reasoning powers they possess. On the days when the experiments were taking place they were practically utterly hungry,  Fig. 1. and so had the best reasons for making every effort to escape. As a fact, their conduct when shut up in these boxes showed the utmost eagerness to get out and get at the much-needed food. Moreover, the actions required and the thinking involved are such as the stories told about intelligent animals credit them with, and, on the other hand, are not far removed from the acts and feelings required in the ordinary course of animal life. It would be foolish to deny reason to an animal because he failed to do something (e. g., a mathematical computation) which in the nature of his life he would never be likely to think about, or which his bones and muscles were not fitted to perform, or which, even by those who credit him with reason, he is never supposed to do. So the experiments were arranged with a view of giving reasoning every chance to display itself if it existed.

Fig. 1. and so had the best reasons for making every effort to escape. As a fact, their conduct when shut up in these boxes showed the utmost eagerness to get out and get at the much-needed food. Moreover, the actions required and the thinking involved are such as the stories told about intelligent animals credit them with, and, on the other hand, are not far removed from the acts and feelings required in the ordinary course of animal life. It would be foolish to deny reason to an animal because he failed to do something (e. g., a mathematical computation) which in the nature of his life he would never be likely to think about, or which his bones and muscles were not fitted to perform, or which, even by those who credit him with reason, he is never supposed to do. So the experiments were arranged with a view of giving reasoning every chance to display itself if it existed.

What, now, would we expect to observe if a reasoning animal, who is surely eager to get out, is put, for example, into a box with a door arranged so as to fall open when a wooden button holding it at the top (on the inside) is turned from its vertical to a horizontal position? We should expect that he would first try to claw the whole box apart or to crawl out between the bars. He would soon realize the futility of this and stop to consider. He might then think of the button as being the vital point, or of having seen doors open when buttons were turned. He might then poke or claw it around. If after he had eaten the bit of fish outside he was immediately put in