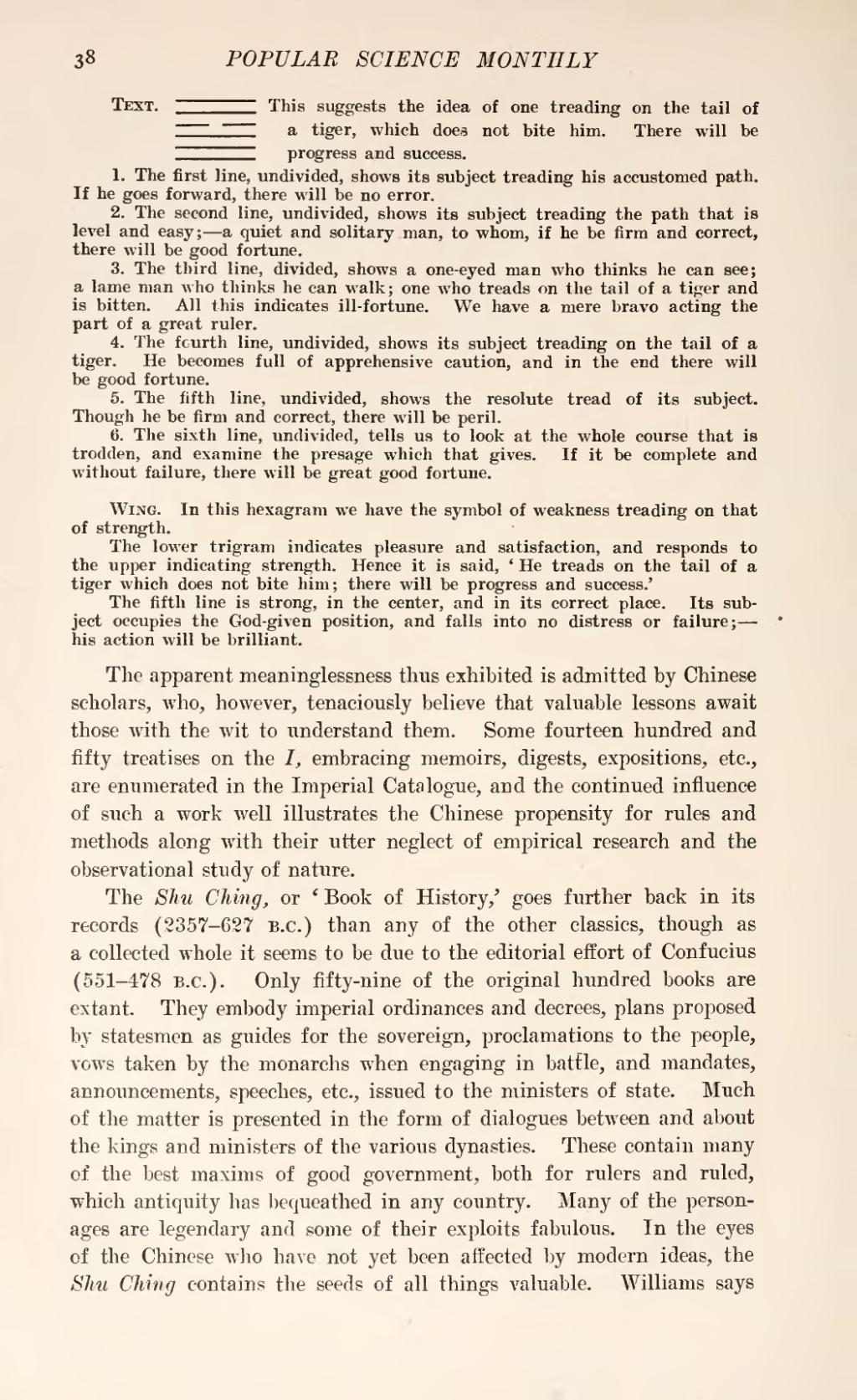

|

1. The first line, undivided, shows its subject treading his accustomed path. If he goes forward, there will be no error.

2. The second line, undivided, shows its subject treading the path that is level and easy;—a quiet and solitary man, to whom, if he be firm and correct, there will be good fortune.

3. The third line, divided, shows a one-eyed man who thinks he can see; a lame man who thinks he can walk; one who treads on the tail of a tiger and is bitten. All this indicates ill-fortune. We have a mere bravo acting the part of a great ruler.

4. The fourth line, undivided, shows its subject treading on the tail of a tiger. He becomes full of apprehensive caution, and in the end there will be good fortune.

5. The fifth line, undivided, shows the resolute tread of its subject. Though he be firm and correct, there will be peril.

6. The sixth line, undivided, tells us to look at the whole course that is trodden, and examine the presage which that gives. If it be complete and without failure, there will be great good fortune.

Wing. In this hexagram we have the symbol of weakness treading on that of strength.

The lower trigram indicates pleasure and satisfaction, and responds to the upper indicating strength. Hence it is said, 'He treads on the tail of a tiger which does not bite him; there will be progress and success.'

The fifth line is strong, in the center, and in its correct place. Its subject occupies the God-given position, and falls into no distress or failure;—his action will be brilliant.The apparent meaninglessness thus exhibited is admitted by Chinese scholars, who, however, tenaciously believe that valuable lessons await those with the wit to understand them. Some fourteen hundred and fifty treatises on the I, embracing memoirs, digests, expositions, etc., are enumerated in the Imperial Catalogue, and the continued influence of such a work well illustrates the Chinese propensity for rules and methods along with their utter neglect of empirical research and the observational study of nature.

The Shu Ching, or 'Book of History,' goes further back in its records (2357-627 B.C.) than any of the other classics, though as a collected whole it seems to be due to the editorial effort of Confucius (551-478 B.C.). Only fifty-nine of the original hundred books are extant. They embody imperial ordinances and decrees, plans proposed by statesmen as guides for the sovereign, proclamations to the people, vows taken by the monarchs when engaging in battle, and mandates, announcements, speeches, etc., issued to the ministers of state. Much of the matter is presented in the form of dialogues between and about the kings and ministers of the various dynasties. These contain many of the best maxims of good government, both for rulers and ruled, which antiquity has bequeathed in any country. Many of the personages are legendary and some of their exploits fabulous. In the eyes of the Chinese who have not yet been affected by modern ideas, the Shu Ching contains the seeds of all things valuable. Williams says