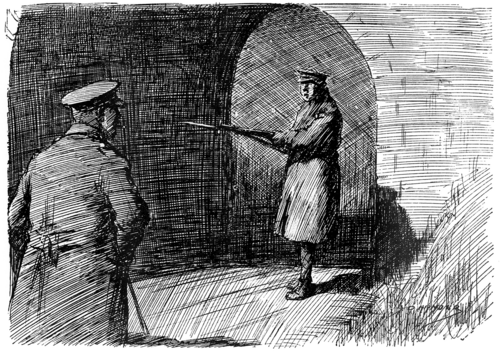

Sentry (on duty for first time). "'Alt! Who goes there? Advance to within five paces, and give the countersign 'Waterloo.'"

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

In the good old days when that royal pipsqueak, our First James, came to the throne, if you were a physician of a little more than common skill and furnished with theological opinions of a modernist complexion, or a lonely woman with (or without) some cunning in the matter of herbs, who cherished a peculiar (or normal) pussy-cat, you were quite likely to be burnt out of hand. And, in her competent way, Mary Johnston, in The Witch (Constable), deals with this dark blot on the escutcheon of Christianity. Through what suffering and what joys Dr. Aderhold, the kindly free-thinking mystic, and Joan Heron, the simple village maid, found their ultimate and, for the times, merciful release by halter in place of fire, readers who have nerves to spare for horror will read with eagerness. It is indeed a dreadful story. Miss Johnston is not one of your novelists who lets herself off the contemporary document, and on her reputation you may take it she is not far out. The grim tale serves to show to what lengths the force of suggestion will, in times of excitement, carry folk otherwise sober and truthful. Manifestly preposterous evidence, freely given, was freely admitted by trained legal minds—evidence on which innocent lives were sacrificed at the average rate of over a thousand a month in England and Scotland in the two centuries of the chief witch-baiting period. But, after all, have we not, most of us, near relations who saw a quarter-of-a-million of astrakanned Russians steal through England in the dead of an August night? And have we not——— But I grow tedious. The Witch is an eminently readable story of adventure of the coincidental kind.

What I like best in the stories of Mr. W. W. Jacobs, apart from their mere hilarity, is their triumphant vindication of the right to jest. They spread themselves before me like a pageant representing the graceful submission of the easy dupe. They tempt me to filch away chairs from beneath stout and elderly gentlemen who are about to sit down. Take the case of Sergeant-Major Farrer in Night Watches (Hodder and Stoughton). He was afraid of nothing on earth, or off it, but ghosts, and he despised the weedy young man who was in love with his daughter. So the weedy young man dared him to come to a haunted cottage at midnight, and, dressed up as a spectre, terrified the soldier into something more than a strategic retreat, with the result that he surrendered his daughter. In real life of course it is different. I know a colour-sergeant, and somehow I rather think that if I—but never mind. In Mr. Jacobs' beautiful world, as it is with Mr. Farrer so is it with Peter Russet, with Ginger Dick and with Sam Small. They know when the laugh is against them, and, waiving the appeal to force or to law, they grumble but retire. There is one exercise in the gruesome in Night Watches, but it hardly shows Mr. Jacobs at his best in this particular vein. There are also several charming illustrations by Mr. Stanley Davis, executed with a buff tint, which help to sustain the gossamer illusion.