are separate, and have been ever since the Civil War.

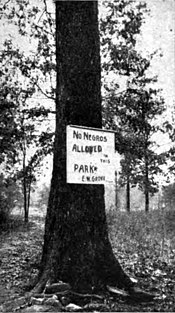

In one of the parks of Atlanta I saw this sign:

No Negroes Allowed in this Park.

Color Line in the Public Library

A story significant of the growing separation of the races is told about the public library at Atlanta, which no Negro is permitted to enter. Carnegie gave the money for building it, and when the question came up as to the support of it by the city, the inevitable color question arose. Leading Negroes asserted that their people should be allowed admittance, that they needed such an educational advantage even more than white people, and that they were to be taxed their share—even though it was small—for buying the books and maintaining the building. They did not win their point, of course, but Mr. Carnegie proposed a solution of the difficulty by offering more money to build a Negro branch library, provided the city would give the land and provide for its support. The city said to the Negroes:

"You contribute the land and we will support the library."

Influential Negroes at once arranged for buying and contributing a site for the library. Then the question of control arose. The Negroes thought that inasmuch as they gave the land and the building was to be used entirely for colored people, they should have one or two members on the board of control. This the city officials, who had charge of the matter, would not hear of; result, the Negroes would not give the land, and the branch library has never been built.

Right in this connection: while I was in Atlanta, the Art School, which In the past has often used Negro models, decided to draw the color line there, too, and no longer employ them.

Formerly Negroes and white men went to the same saloons, and drank at the same bars, as they do now, I am told, in some parts of the South. In a few instances, in Atlanta, there were Negro saloon-keepers, and many Negro bartenders. The first step toward separation was to divide the bar, the upper end for white men, the lower for Negroes. Finally, after the riot, all Negro saloon-keepers were thrown out of business, and by the new requirement no saloon can serve both white and colored men.

Consequently, going along Decatur Street, one sees the saloons designated by conspicuous signs:

"Whites Only."

"Colored Only."

And when the Negro suffers the ordinary consequences of a prolonged visit to Decatur Street, and finds himself in the city prison, he is separated there, too, from the whites. And afterwards in court, if he comes to trial, two Bibles are provided; he may take his oath on one; the other Is for the white man. When he dies he is burled in a separate cemetery.

One curious and enlightening example of the infinite ramifications of the color line was given me by Mr. Logan, secretary of the Atlanta Associated Charities, which is supported by voluntary contribution. One day, after the not, a subscriber called Mr. Logan on the telephone and said: