Popular Science Monthly/Volume 12/February 1878/The Growth of the Steam-Engine IV

| THE GROWTH OF THE STEAM-ENGINE.[1] |

By Professor R. H. THURSTON,

OF THE STEVENS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY.

IV.

STEAM-NAVIGATION.

72. Among the most interesting of the applications of steam-power, to the political economist and to the historian, as well as to the engineer, is its use in ship-propulsion.

In the modern marine engine we find one of the most important adaptations of steam machinery and the greatest of all the triumphs of the mechanical engineer.

Although, as has been already stated in previous lectures, attempts had been made, before the beginning of the present century, to successfully effect this application of the power of steam, they did not succeed, in any instance, as commercial enterprises, until after that date.

Indeed, it is but a few years ago that the passage across the Atlantic was made by sailing-vessels almost exclusively, and that the dangers, the discomforts, and the irregularities of their trips were most serious.

Now, hardly a day passes that does not see several large and powerful steamers leaving the ports of New York and Liverpool to make the same voyages; and their passages are made with such regularity and safety that travelers can anticipate, with confidence, the time which will mark the termination of their voyage, predicting the day and almost the hour of their arrival, and can cross with safety and comparative comfort, even amid the storms of winter.

Yet, all that we to-day see of the extent and the efficiency of steam-navigation has been the work of the present century; and it may well excite both our wonder and our admiration.

73. The history of this development of the use of steam-power illustrates, more perfectly than any other, that process of the growth of this invention which has been already referred to. We can here trace it, step by step, from the earliest and rudest devices up to those most recent and most perfect designs, which represent the most successful existing types of the heat-engine—whether considered with reference to its design and construction, or as the highest application of known scientific principles—that have yet been found attainable in even the present advanced state of the mechanic arts.

74. This application of the force of steam was very possibly anticipated 800 years ago by Roger Bacon, that learned Franciscan monk who, in an age of ignorance and intellectual torpor, wrote:

For many years before even the first promising effort had been made, the minds of the more intelligent had been prepared to appreciate the invention when it should finally be brought forward, and were ready for even greater wonders than have yet been accomplished.

75. The earliest attempt to propel a vessel by steam is claimed, by Spanish authorities, as it has been stated, to have been made by Blasco de Garay in the harbor of Barcelona, Spain, in 1543.

The account seems somewhat apocryphal, and the experiment, if made, certainly led to no useful results.

76. In an anonymous English pamphlet, published in 1651,[2] which is supposed, by Stuart, to have been written by the Marquis of Worcester, an indefinite reference to what may probably have been the steam-engine is made, and it is there stated to be capable of successful application to propelling boats.

77. In 1690 Papin proposed to use his piston-engine to drive paddle-wheels to propel vessels; and in 1707 he applied the steam-engine, which he had proposed as a pumping-engine, to driving a model boat on the Fulda, at Cassel.

In this trial he probably used the arrangement of which a sketch

Fig. 44.—Papin's Marine Engine, 1707.

is here shown. His pumping-engine forced up water to turn a water-wheel, which, in turn, was made to drive the paddles, as in Fig. 44. An account of his experiment is to be found in manuscript in the correspondence between Leibnitz and Papin, preserved in the Royal Library at Hanover.

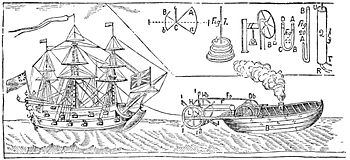

78. December 21, 1736, Jonathan Hulls took out an English patent for the use of a steam-engine for ship-propulsion, proposing to employ his steamboat in towing.

In 1737 he published a well-written pamphlet[3] describing this apparatus, an engraving of which is here shown in fac-simile.

Fig. 45.—Hulls's Steam Towboat, 1787.

He proposed using the Newcomen engine, fitted with a counterpoise weight, and a system of ropes and grooved wheels, which, by a peculiar ratchet-like action, gave a continuous rotary motion.

There is no positive evidence that Hulls ever put his scheme to the test of experiment, although tradition does say that he made a model, which he tried with such ill success as to prevent his further prosecution of the experiment. Doggerel rhymes are still extant which were, it is said, sung by his neighbors in derision of his folly, as they considered it.

79. William Henry, of Chester County, Pennsylvania, is said to have constructed a model steamboat in 1763. It was a failure, although not a discouraging one.

80. In 1774 the Comte d'Auxiron, a French nobleman, and a gentleman of some scientific attainments, constructed a steamboat, and tried it on the Seine, with the aid of M. Perier.

This experiment proving unsuccessful, M. Perier built another boat, which he tried independently in 1775, but was again unsuccessful, owing principally to the small power of his engine.

81. In 1778, and again in 1781 or 1782, the French Marquis de Jouffroy, who, in his later experiments, used quite a large vessel, succeeded in obtaining such good results as to encourage him to persevere, but, political disturbances driving him from his country, his labors terminated abruptly.

82. About 1785 John Fitch and James Rumsey, two ingenious American mechanics, were engaged in experiments having in view the application of steam to navigation.

83. Rumsey's experiments began in 1774, and in 1786 he succeeded in driving a boat at the rate of four miles an hour against the current of the Potomac, at Shepardstown, Maryland.

Rumsey employed his engine to drive a great pump, which forced a stream of water aft, thus propelling the boat forward.

This same method has been recently tried again by the British Admiralty in the Water-witch, a gunboat of moderate size, using a centrifugal pump to set in motion the propelling stream, and with some other modifications which are decided improvements upon Rumsey's rude arrangements, but which have not done much more than did his toward the introduction of "hydraulic propulsion," as it is now called.

Rumsey died of apoplexy while explaining some of his schemes before a London society a short time later.

84. John Fitch was an unfortunate and eccentric, but very ingenious, Connecticut mechanic.

After roaming about until forty years of age, he finally settled on the banks of the Delaware, where he built his first steamboat.

In 1788 he obtained a patent for the application of steam to navigation.

His boat is shown in Fig. 46; it was sixty feet long and twenty

Fig.—46 John Fitch, 1788.

feet wide. The propelling apparatus was a system of paddles, which were suspended by the upper ends of their shafts, and moved by a series of cranks, one to each, taking hold at the middle, and giving them almost exactly the motion which is imparted to his paddle by the Indian in his canoe.

Fig. 47 exhibits a sketch, reëngraved from a French work, which illustrates at once another of Fitch's steamboats and the Gallic artist's idea of the flora on the banks of the Delaware.

Fitch, while urging the importance and the advantages of his plan, confidently stated his belief that the ocean would soon be

| Fig. 47.—An Ideal Sketch of the Delaware. | Fig. 48.—Steamboat on Dalswinton Lake, 1788. |

crossed by steam-vessels, and that the navigation of the Mississippi would also become exclusively a steam-navigation.

Fitch's boat, when tried at Philadelphia, was found capable of making eight miles an hour. It was laid up in 1792.

85. In 1788 Patrick Miller, James Taylor, and William Symmington, attached a steam-engine to a boat with paddle-wheels, which had been built by the first-named, and tried it for the first time on Dalswinton Lake, in Dumfriesshire, Scotland.

This boat, having attained a speed of five miles an hour, another was constructed (Fig. 48), and was tried in 1789. This vessel was

Fig. 49.—The Charlotte Dundas, 1801.

driven by an engine of twelve-horse power, and made seven miles an hour. This result, encouraging as it was, led to no further immediate action, the funds of the experimenters having failed.

86. In 1801, however, Symmington was employed by Lord Dundas to construct a steamboat, with the design of substituting steam for horse-power on canals.

After several trials, Symmington, whose experience, with Miller and Taylor, had been of much service in directing his experiments, completed a towboat, of which a sectional view is seen in Fig. 49, which he fitted with a stern-paddle wheel and a double-acting crank-engine of twenty-two inches diameter of cylinder and four feet stroke. This boat attained a speed of six miles an hour; but was laid aside, although perfectly successful, in consequence of a fear of injuring the banks of the canal by the waves produced by it.

Robert Fulton.

The Charlotte Dundas, as this boat was named, was so evidently a success that the Duke of Bridgewater ordered eight similar vessels for his canal; but his death, soon afterward, prevented the order being filled.

87. At this time, several American mechanics were also still working at this attractive problem.

In 1802-'3, Robert Fulton, with our other distinguished country-man, Mr. Joel Barlow, the patentee of the "Barlow boiler" (Fig. 50), in whose family he resided, and Chancellor Livingston, who had at that time taken up a temporary residence in Paris, commenced a small steamboat eighty-six feet long and of eight feet beam. The hull was altogether too slight to bear the weight of the machinery, and, when almost completed, the little craft literally broke in two, and sank at her moorings.

The wreck was promptly recovered and rebuilt, and in August, 1803, the trial-trip was made in presence of a large party of invited guests.

Fig. 50.—Water-tube Boiler of Fulton and Barlow, 1793.

88. The experiment was sufficiently successful to induce Fulton and Livingston to order an engine of Messrs. Boulton and Watt, directing it to be sent to America, where Livingston soon returned. In 1806 Fulton followed, reaching New York in December, and at once going to work on the vessel for which the English firm sent the engine, without being informed of its intended use.

In the spring of 1807 the Clermont (Fig. 51), as the new boat

Fig. 51.—The Clermont, 1807.

was christened, was launched from the ship-yard of Charles Brown, on the East River, New York.

In August, the machinery was on board, and in successful operation. The hull of this boat was one hundred and thirty-three feet long, eighteen feet beam, and seven feet in depth.

The boat soon afterward made a trip to Albany, making the distance of one hundred and fifty miles in thirty-two hours running time, and returning in thirty hours. The sails were not used on either occasion.

This was the first voyage of considerable length ever made by a steam-vessel, and the Clermont was soon after regularly employed as a passenger-boat between the two cities.

Fulton, though not to be classed with James Watt as an inventor, is entitled to the great honor of having been the first to make steam-navigation an every-day commercial success, and of having thus made the first application of the steam-engine to ship-propulsion which was not followed by the retirement of the experimenter from the field of his labors before success was permanently insured.

89. The engine of the Clermont (Fig. 52), was of rather peculiar

Fig. 52.—Engine of the Clermont, 1807.

form, the engine being coupled to the crank-shaft by a bell-crank, and the paddle-wheel shaft being separated from the crank-shaft, but connected with the latter by gearing. The cylinders were twenty-four inches in diameter and of four feet stroke. The paddle-wheels had buckets four feet long, with a dip of two feet.

An old drawing made by Fulton's own hand, showing this engine as it was improved in 1808, is in the relic-corner of the lecture-room of the author at the Stevens Institute of Technology.

The voyage of this steamer to Albany was attended with some ludicrous incidents, which found their counterparts whenever subsequently steamers were for the first time introduced.

90. Mr. Colden, the biographer of Fulton, says that she was described by persons who had seen her passing at night, "as a monster moving on the waters, defying wind and tide, and breathing flames and smoke."

This first steamboat used dry pine-wood for fuel, and the flame rose to a considerable distance above the smoke-pipe, and, when the fires were disturbed, mingled smoke and sparks rose high in the air.

"This uncommon light," says Colden, "first attracted the attention of the crews of other vessels. Notwithstanding the wind and tide were averse to its approach, they saw with astonishment that it was rapidly coming toward them, and, when it came so near that the noise of the machinery and paddles was heard, the crews (if what was said in the newspapers of the time be true), in some instances, shrunk beneath their decks from the terrific sight, and left their vessels to go on shore; while others prostrated themselves, and besought Providence to protect them from the approach of the horrible monster which was marching on the tides, and lighting its path by the fires which it vomited."

91. Subsequently, Fulton built several steamers and ferry-boats, to ply about the waters of the States of New York and of Connecticut.

The Clermont was a boat of but 160 tons burden; the Car of Neptune, built in 1807, was 295 tons; the Paragon, in 1811, measured 331; the Richmond, 1813, 370 tons; and the Fulton, the first built in 1814-'15, measured 2,475 tons. The latter vessel, whose size was simply enormous for that time, was what was then considered an exceedingly formidable steam-battery, and was built for the United States Navy.

Before the completion of this vessel, Fulton died of disease resulting from exposure, February 24, 1815, and his death was mourned as a national calamity.

92. But Fulton had some active and enterprising rivals.

Oliver Evans.

Oliver Evans had, in 1801 or 1802, sent one of his engines, of about 150 horse-power, to New Orleans, for the purpose of using it to propel a vessel, owned by Messrs. McKeever and Valcourt, which was there awaiting it.

The engine was actually set up in the boat, but at a low stage of the river, and no trial could be made until the river should again rise, some months later. Having no funds to carry them through so long a period, Evans's agents were induced to remove the engine again, and to set it up in a saw-mill, where it created great astonishment by its extraordinary performance in sawing lumber.

- ↑ An abstract of "A History of the Growth of the Steam-Engine," to be published by D. Appleton & Co.

- ↑ "Inventions of Engines of Motion, recently brought to Perfection," London, 1651. A number of such treatises, vaguely hinting at new motors for propulsion of vessels, appeared during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

- ↑ "A Description and Draught of a Newly-invented Machine for carrying Vessels or Ships out of or into any Harbor, Port, or River, against Wind and Tide, and in a Calm," London, 1737.