Popular Science Monthly/Volume 19/June 1881/Degeneration I

| DEGENERATION. |

By Dr. ANDREW WILSON.

IT can not be gainsaid that a survey of the fields of life around us impresses one with the idea that the general tendencies of living nature gravitate toward progression and improvement, and are modeled on lines which, as Von Baer long ago remarked, lead from the general or simple toward the definite special and complex. This much is admitted on all hands, and the ordinary courses of life substantiate the aphorism that progress from low grades and humble ways is the law of the organic universe that hems us in on every side, and of which, indeed, we ourselves form part. The growth of plant-life, which runs concurrently with the changing seasons of the year, impresses this fact upon us, and the history of animal development but repeats the tale. From seed to seed-leaf, from seed-leaf to stem and leaves, from simple leaves to flower, and from flower to fruit, there is exhibited a natural progress in plant-existence, which testifies eloquently enough, by analogy at least, to the existence of like tendencies in all other forms of life. Similarly, in the animal host, progressive change is seen to convert that which is literally at first "without form and void" into the definite structure of the organism. A minute speck of protoplasm on the surface of the egg—a speck that is indistinguishable, in so far as its matter is concerned, from the materies of the animalcule of the pool is the germ of the bird of the future. Day by day the forces and powers of development weave the protoplasm into cells, and the cells into bone and muscle, sinew and nerve, heart and brain. In due season the form of the higher vertebrate is evolved, and progressive change is once more illustrated before the waiting eyes of life-science. But the full meaning of most problems which life-science presents to view is hardly gained by a merely cursory inspection of what may be called the normal side of things. The by-paths of development—more frequently, perhaps, than its beaten tracks—reveal guiding clews and traces of the manner in which the progress in question has come to pass. So, also, the side-avenues of biology open up new phases of, it may be, the main question at issue, and may reveal, as in the present instance, an interesting reverse to the aspects we at first deem of sole and paramount importance. For example, a casual study of the facts of animal development is well calculated to show that life is not all progress, and that it includes retrogression as well as advance. Physiological history can readily be proved to tend in many cases toward backsliding, instead of reaching forward and upward to higher levels. This latter tendency, beginning now to be better recognized in biology than of late years, can readily be shown to exercise no unimportant influence on the fortunes of animals and plants. In truth, life at large must now be regarded as existing between two great tendencies—the one progressive and advancing, the other retrogressive and degenerating. Such a view of matters may serve to explain many things in living histories which have hitherto been regarded as somewhat occult and difficult of solution; while we may likewise discover that the coexistence of progress and retrogression is a fact perfectly compatible with the lucid opinions and teachings concerning the origin of living things which we owe to the genius of Darwin and his disciples.

A fundamental axiom of modern biology declares that in the development of a living being we may discern a panoramic unfolding, more or less complete, of its descent. "Development repeats descent" is an aphorism which cultured biology has everywhere writ large over its portals. Rejecting this view of what development teaches, the phases through which animals and plants pass in the course of their progress from the germ to the adult stage present themselves to view as simply meaningless facts and useless freaks and vagaries of Nature. Accepting the idea—favored, one may add, by every circumstance of life-science—much that was before wholly inexplicable becomes plain and readily understood. And the view that a living being's development is really a quick and often abbreviated summary of its evolution and descent both receives support from and gives countenance to the general conclusion that life's forces tend as a rule toward progress, but likewise exhibit retrogression and degeneration. If a living being is found to begin its history, as all animals and plants commence their existence, as a speck of living jelly, comparable to the animalcule of the pool, it is a fair and logical inference that the organisms in question have descended from lowly beings, whose simplicity of structure is repeated in the primitive nature of the germ. If, to quote another illustration, the placid frog of to-day, after passing through its merely protoplasmic stage, appears before us in the likeness of a gill-breathing fish (Fig. 1), the assumption is plain and warrantable that the frog

Fig. 1.—Development of Frog.

race has descended from some primitive fish stock, whose likeness is reproduced with greater or less exactness in the tadpoles of the ditches. Or if, to cite yet another example, man and his neighbor quadrupeds (Fig. 2), birds, and reptiles, which never breathe by gills at any period of their existence, are found in an early stage of development to possess "gill-arches" (g), such as we naturally expect to see, and such as we find in the fishes themselves, the deduction that these higher animals are descended from gill-bearing or aquatic ancestors admits of no denial. On any other theory, the existence of gill-arches in the young of an animal which never possesses gills is to be viewed as an inexplicable freak of Nature—a dictum which, it is needless to remark, belongs to an era one might well term prescientific, in comparison with the "sweetness and light" of these latter days.

| Fig. 2.—Pig | Calf. | Rabbit. | Man. |

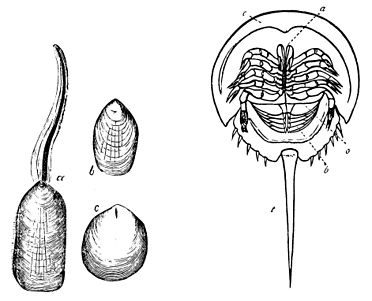

Hanging very closely on the aphorism respecting development and its meaning, is another biological axiom, wellnigh as important as the former. If development teaches that life has been and still is progressive in its ways, and that the simpler stages in an animal's history represent the conditions of its earliest ancestors, it is a no less stable proposition that at all stages of their growth living beings are subject to the action of outward and inward forces. Every living organism lives under the sway and dominance of forces acting upon it from without, and which it is enabled to modify and to utilize by its own inherent capabilities of action. It is, in fact, the old problem of the living being and its surroundings applied to the newer conceptions of life and nature which modern biology has revealed. The living thing is not a stable unit in its universe, however wide or narrow that sphere may be. On the contrary, it exists in a condition of continual war, if one may so put it, between its own innate powers of life and action, of living and being, and the physical powers and conditions outside. This much is now accepted by all scientists. Differences of opinion certainly exist as to the share which the internal constitution of the living being plays in the drama of life and progress. It seems, however, most reasonable to conclude that two parties exist to this, as to every other bargain; and, regarding the animal or plant as plastic in its nature, we may assume such plasticity to be modified on the one hand by outside forces, and on the other by internal actions proper to the organism as a living thing. Examples of such tendencies of life are freely scattered everywhere in Nature's domain. For instance, we know of many organisms which have continued from the remotest ages to the present time, without manifest change of form or life, and which appear before us to-day the living counterparts of their fossilized representatives of the chalk, or it may be of Silurian or Cambrian times. The lamp-shells (Terebratula) of the chalk exist in our own seas with wellnigh inappreciable differences. The Lingula or Lingulella (Fig. 3, a), another genus of these animals, has persisted from the Cambrian age (b, c) to our own times, presenting little or no change for the attention of the geological chronicler. The curious king-crabs, or Limuli (Fig. 4), of the West Indies are likewise presented

| Fig. 3.—Lingula. | Fig. 4.—King Crab. |

to our view, with little or no variation, from very early ages of cosmical history; and of the pearly nautilus (Fig. 8)—now remaining as the only existing four-gilled and externally shelled cuttle-fish—the same remark holds good. The fishes, likewise, are not without their parallel instances of lack of change and alteration throughout long ages of time. The well-known case of the genus Beryx presents us Fig. 5.—Beryx. with a fish of high organization, found living in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and which possesses fossil representatives and facsimiles in the chalk (Fig. 5.) From the latter period to the present day, the genus Beryx has therefore undergone little modification or change. The same remark certainly holds good of many of those huge "dragons of the prime" (Figs. 6 and 7), which reveled in the seas of the Trias, Oölite, and Chalk epochs—developed in immense numbers in these eras of earth's history, but disappearing for ever from the lists of living things at the close of the Cretaceous age, and exhibiting little or no change during their relatively brief history.

Fig. 5.—Beryx. with a fish of high organization, found living in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and which possesses fossil representatives and facsimiles in the chalk (Fig. 5.) From the latter period to the present day, the genus Beryx has therefore undergone little modification or change. The same remark certainly holds good of many of those huge "dragons of the prime" (Figs. 6 and 7), which reveled in the seas of the Trias, Oölite, and Chalk epochs—developed in immense numbers in these eras of earth's history, but disappearing for ever from the lists of living things at the close of the Cretaceous age, and exhibiting little or no change during their relatively brief history.

Such cases of stability amid conditions which might well have favored change, and which saw copious modification and progression in other groups of animals, might at first sight be regarded as presenting a serious obstacle to the doctrine of progressive development on which the whole theory of evolution depends. As such an obstacle, the series of facts in question was long regarded; as such, these facts are sometimes even now advanced, but only by those who imperfectly appreciate and only partially understand what the doctrine of evolution teaches and what its leading idea includes. Even Cuvier himself, when advancing the case of the apparently unchanged mummies of Egyptian animals against Lamarck's doctrine of descent, failed—possibly through the imperfectly discussed stage in which the whole question rested in his day—to understand that the very facts of preservation revealed in the monuments of Egypt testified to the absence of those physical changes which could alone have affected the animals of the Nile land. But the fuller consideration of that theory of nature which credits progressive change as the usual way of life, shows us that it is no part of evolution to maintain either that living beings must needs undergo continual change, or that they must change and modify at the same rate. On the contrary, Mr. Darwin, in his classic work, maintains exactly the opposite proposition. There are, in fact, two great factors at work in living nature—a tendency to vary and change, and the influence of environments or surroundings. Given the first tendency, which is not at all a matter of dispute, the influence of the second is plainly enough discernible in bringing to the front either the original,

Figs. 6 and 7.—Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus.

primitive, or, as it might be named, the parent form, or the varying forms which are produced by modification of the parent. As it has well been put: "Granting the existence of the tendency to the production of variations, then, whether the variations which are produced shall survive and supplant the parent, or whether the parent form shall survive and supplant the variations, is a matter which depends entirely on those conditions which give rise to the struggle for existence. If the surrounding conditions are such that the parent form is more competent to deal with them and flourish in them than the derived forms, then in the struggle for existence the parent form will maintain itself, and the derived forms will be exterminated. But, if, on the contrary, the conditions are such as to be more favorable to a derived than to the parent form, the parent form will be extirpated, and the derived form will take its place. In the first case, there will be no progression, no change of structure, through any imaginable series of ages; in the second place, there will be modification and change of form." To the same end Darwin himself leads us. In one or two very pregnant passages, the author of the "Theory of Natural Selection" very plainly indicates why progression should not be universal, and why certain beings remain lowly organized while others attain to the summit and pinnacle of their respective organizations. "How is it," says Darwin, "that throughout the world a multitude of the lowest forms still exist? and how is it that in each great class some forms are far more highly developed than others? Why have not the more highly developed forms everywhere supplanted and exterminated the lower?" Answering his own queries, Darwin says that natural selection by no

Fig. 8.—Pearly Nautilus.

means includes "progressive development—it only takes advantage," he remarks, "of such variations as arise and are beneficial to each creature under its complex relations of life. And it may be asked, what advantage, as far as we can see, would it be to an infusorian animalcule—to an intestinal worm—or even to an earthworm, to be highly organized? If it were no advantage, these forms would be left, by natural selection, unimproved or but little improved, and might remain for ages in their present lowly condition. And geology tells us that some of the lowest forms, as the foraminifera (Fig. 9), infusoria, and rhizopods, have remained for an enormous period in nearly their present state. But," adds Darwin, with a characteristically impartial view of matters, "to suppose that most of the many now existing low forms have not in the least advanced since the first dawn of life would be extremely rash; for every naturalist who has dissected some of the beings now ranked as very low in the scale must have been struck with their really wondrous and beautiful organization."

|

| Fig. 9.—Globigerina, etc. |

Thus one of the plainest facts of natural history, namely, that in even one group or class of animals we find forms of exceedingly low structure included along with animals of high organization—the apparently diverse bodies being really modeled on the one and the same type—is explained by the consideration that with different conditions, or with various conditions acting differently upon unlike constitutions, we expect to find extreme differences in the rank to which the members of a class may attain. In the class of fishes we find the worm-like, clear-bodied lancelet of an inch long; associated with the ferocious shark, the active dogfish, or the agile food-fishes of our table. But, as Darwin remarks, the shark would not tend to supplant the lancelet, their spheres and their conditions of existence being of diverse nature. The same remark applies to many other classes of living beings. So that lowly beings still live as such among us, and preserve the primitive simplicity of their race, firstly, because the conditions of life and their limited numbers may not have induced any great competition or struggle for existence. On the "let-well-alone" principle we may understand why some animals, such as the lancelet itself, have lagged behind in the race after progress. Then, secondly, as Darwin remarks, favorable variations, by way of beginning the work of progress, may never have appeared—a result due, probably, as much to hidden causes within the living being as to outside conditions. We may not fail to note, lastly, that the simpler and more uniform these latter conditions are—as represented in the abysses of the ocean, for example—the less incentive is there for the progress and evolution of the races which dwell in their midst.

This somewhat lengthy introduction to the subject of degeneration and its results is in its way necessary for the full appreciation of the fashion in which degeneration relates itself to the other conditions of life. From the preceding reflections it becomes clear that three possibilities of life await each living being. Either it remains primitive and unchanged, or it progresses toward a higher type, or, last of all, it backslides and retrogresses. As the first condition, that of stability, is, as already noted, perfectly consistent with the doctrine of descent, so are the two latter conditions part and parcel of that theory. The stable state forces the animal to remain as it now is, or as it has been in all times past; the progressive tendency will make it a more elaborate animal: and the progress of degeneration will, on the other hand, tend to simplify its structure. It requires no thought to perceive that progress is a great fact of nature. The development of every animal and plant shows the possibilities of nature in this direction. But the bearings of degeneration and physiological backsliding are not, perchance, so clearly seen; hence, to this latter aspect of biology we may now specially direct our attention.

That certain animals degenerate or retrogress in their development before our eyes to-day, is a statement susceptible of ready and familiar illustration. No better illustrations of this statement can be found than those derived from the domain of parasitic existence. When an Fig. 10.-Common Tapeworm (Tæna `solium). 1. The head extremity, magnified showing hooks (a) and suckers (b, c); d, neck, with immature joints. 2. A joint largely magnified showing branching "ovary" in which the numerous eggs of each joint are matured. animal or plant attaches itself partly or wholly to another living being, and becomes more or less dependent upon the latter for support and nourishment, it exhibits, as a rule, retrogression and degeneration. The parasitic "guest" dependent on its "host" for lodging alone, or it may be for both board and lodging, is in a fair way to become degraded in structure, and, as a rule, exhibits degradation of a marked kind, where the association has persisted sufficiently long. Parasitism and servile dependence act very much in structural lower life as analogous instances of mental dependence on others act in ourselves. The destruction of characteristic individuality and the extinction of personality are the natural results of that form of association wherein one form becomes absolutely dependent on another for all conditions of life. A life of attachment exhibits similar results, and organs of movement disappear by the law of disuse. A digestive system is a superfluity to an animal which, like a tapeworm (Fig. 10), obtains its food ready-made in the very kitchen, so to speak, of its host. Hence the lack of a digestive apparatus follows the finding of a free commissariat by the parasite. Organs of sense are not necessary for an attached and rooted animal; these latter, therefore, go by the board, and the nervous system itself becomes modified and altered. Degradation, wholesale and complete, is the penalty the parasite has to pay for its free board and lodging; and in this fashion Nature may be said to revenge the host for the pains and troubles wherewith, like the just of old, he may be tormented. Numerous life-histories testify clearly enough to the correctness of the foregoing observations. Take, as an example, the history of Sacculina (Fig. 11, a), which exists as a bag-like growth attached to the bodies of hermit-crabs, and sends root-like processes into the liver of its host. No sign of life exists in a

Fig. 10.-Common Tapeworm (Tæna `solium). 1. The head extremity, magnified showing hooks (a) and suckers (b, c); d, neck, with immature joints. 2. A joint largely magnified showing branching "ovary" in which the numerous eggs of each joint are matured. animal or plant attaches itself partly or wholly to another living being, and becomes more or less dependent upon the latter for support and nourishment, it exhibits, as a rule, retrogression and degeneration. The parasitic "guest" dependent on its "host" for lodging alone, or it may be for both board and lodging, is in a fair way to become degraded in structure, and, as a rule, exhibits degradation of a marked kind, where the association has persisted sufficiently long. Parasitism and servile dependence act very much in structural lower life as analogous instances of mental dependence on others act in ourselves. The destruction of characteristic individuality and the extinction of personality are the natural results of that form of association wherein one form becomes absolutely dependent on another for all conditions of life. A life of attachment exhibits similar results, and organs of movement disappear by the law of disuse. A digestive system is a superfluity to an animal which, like a tapeworm (Fig. 10), obtains its food ready-made in the very kitchen, so to speak, of its host. Hence the lack of a digestive apparatus follows the finding of a free commissariat by the parasite. Organs of sense are not necessary for an attached and rooted animal; these latter, therefore, go by the board, and the nervous system itself becomes modified and altered. Degradation, wholesale and complete, is the penalty the parasite has to pay for its free board and lodging; and in this fashion Nature may be said to revenge the host for the pains and troubles wherewith, like the just of old, he may be tormented. Numerous life-histories testify clearly enough to the correctness of the foregoing observations. Take, as an example, the history of Sacculina (Fig. 11, a), which exists as a bag-like growth attached to the bodies of hermit-crabs, and sends root-like processes into the liver of its host. No sign of life exists in a

Fig. 11.—Sacculina and Young.

sacculina beyond mere pulsation of the sac-like body, into and from which water flows by an aperture. Lay open this sac, and we shall find the animal to be a bag of eggs and nothing more. But trace the development of a single egg, and one may derive therefrom lessons concerning living beings at large, and open out issues which spread and extend far afield from sacculina and its kin. Each egg of the sac-like organism develops into a little active creature, possessing three pairs of legs, generally a single eye, but exhibiting no mouth or digestive system—parasitism having affected the larva as well as the adult. Sooner or later, this larva—known as the nauplius (b)—will develop a kind of bivalve shell; the two hinder pairs of limbs are cast off and replaced by six pairs of short swimming-feet; while the front pair of limbs develops to form two elongated organs whereby the young sacculina will shortly attach itself to a crab "host." When the latter event happens, the six pairs of swimming-feet are cast off, the body assumes its sac-like appearance, and the sacculina sinks into its adult stage—a pure example of degradation by habit, use, and wont. So also with certain near neighbors of these crab-parasites, such as the Lerneans, which adhere to the gills of fishes. Beginning life as a three-legged "nauplius," the lernean retrogresses and generates to become a mere elongated worm, devoted to the production of eggs, and exhibiting but little advance on the sacculina. There are dozens of low crustaceans which, like sacculina, afford examples of animals which are free and locomotive in the days of their youth, but which, losing eyes, legs, digestive system, and all the ordinary belongings of animal life, "go to the bad," as a natural result of participating in what has been well named "the vicious cycle of parasitism."

Plainly marked as are the foregoing cases, there are yet other familiar crustaceans which, although not parasites, as a rule, nevertheless illustrate animal retrogression in an excellent manner. Such are the sea-acorns (Balani), which stud the rocks by thousands at low- Fig. 12.—Barnacles. water mark, and such are the barnacles (Fig. 12), that adhere to floating timber and the sides of ships. In the development of sea-acorns and barnacles, the first stage is essentially like that of the sacculina. The young barnacle is a "nauplius," three-legged, free-swimming, single-eyed, and possessing a mouth and digestive apparatus. In the next stage we again meet with the six pairs of swimming-feet seen in sacculina, with the enormously developed front pair of legs serving as "feelers," and with two "magnificent compound eyes," as Darwin describes the organs of vision. The mouth in this second stage, however, is closed, and feeding is there impossible. As Darwin remarks, the function of the young barnacles "at this stage is to search out by their well-developed organs of sense and to reach by their active powers of swimming a proper place on which to become attached, and to undergo their final metamorphosis. When this is completed," adds Darwin, "they are fixed for life; their legs are now converted into prehensile organs; they again obtain a well-constructed mouth, but they have no antennae, and their two eyes are now reconverted into a minute, single, simple eye-spot." A barnacle is thus simply a highly modified crab-like animal which fixes itself by its head to the floating log, and which "kicks its food into its mouth with its feet," to use the simile and description of biological authority. The development of its "shell" and stalk are matters which do not in the least concern its place in the animal series. These latter are local and personal features of the barnacle tribe. For in the "sea-acorns," which pass through an essentially similar development, there is no stalk; and the animal, after its free-swimming stage, simply glues its head, by a kind of marine cement of its own manufacture, to the rock, develops its conical shell, and like the barnacle uses its modified feet as means for exercising the commissariat and nutritive function. It is true that in some respects the adult barnacle may be regarded as lower than the young, and therefore as a degenerate being. Thus, it is lower when eyes, feelers, and movements are taken into account. In other respects the adult may be considered of higher organization than the larva. These higher traits we may logically enough suppose represent the special advances which adult barnacle-life has made on its own account. But, on the whole, degradation and retrogression, if not so fully exemplified as in the sacculina, is still plainly enough illustrated in barnacle history. When we further reflect that even such high crustaceans as prawns and allied forms begin life each as a "nauplius" or under an allied guise, we not only merely discover the common origin of all crustaceans in some form represented by the "nauplius" of to-day, but we also witness the possibilities of development which have placed shrimps, prawns, etc., in the foremost rank of the class, and which, conversely, have left the barnacles and sacculinas, through the action of degenerative changes, among the groundlings of the group.

Fig. 12.—Barnacles. water mark, and such are the barnacles (Fig. 12), that adhere to floating timber and the sides of ships. In the development of sea-acorns and barnacles, the first stage is essentially like that of the sacculina. The young barnacle is a "nauplius," three-legged, free-swimming, single-eyed, and possessing a mouth and digestive apparatus. In the next stage we again meet with the six pairs of swimming-feet seen in sacculina, with the enormously developed front pair of legs serving as "feelers," and with two "magnificent compound eyes," as Darwin describes the organs of vision. The mouth in this second stage, however, is closed, and feeding is there impossible. As Darwin remarks, the function of the young barnacles "at this stage is to search out by their well-developed organs of sense and to reach by their active powers of swimming a proper place on which to become attached, and to undergo their final metamorphosis. When this is completed," adds Darwin, "they are fixed for life; their legs are now converted into prehensile organs; they again obtain a well-constructed mouth, but they have no antennae, and their two eyes are now reconverted into a minute, single, simple eye-spot." A barnacle is thus simply a highly modified crab-like animal which fixes itself by its head to the floating log, and which "kicks its food into its mouth with its feet," to use the simile and description of biological authority. The development of its "shell" and stalk are matters which do not in the least concern its place in the animal series. These latter are local and personal features of the barnacle tribe. For in the "sea-acorns," which pass through an essentially similar development, there is no stalk; and the animal, after its free-swimming stage, simply glues its head, by a kind of marine cement of its own manufacture, to the rock, develops its conical shell, and like the barnacle uses its modified feet as means for exercising the commissariat and nutritive function. It is true that in some respects the adult barnacle may be regarded as lower than the young, and therefore as a degenerate being. Thus, it is lower when eyes, feelers, and movements are taken into account. In other respects the adult may be considered of higher organization than the larva. These higher traits we may logically enough suppose represent the special advances which adult barnacle-life has made on its own account. But, on the whole, degradation and retrogression, if not so fully exemplified as in the sacculina, is still plainly enough illustrated in barnacle history. When we further reflect that even such high crustaceans as prawns and allied forms begin life each as a "nauplius" or under an allied guise, we not only merely discover the common origin of all crustaceans in some form represented by the "nauplius" of to-day, but we also witness the possibilities of development which have placed shrimps, prawns, etc., in the foremost rank of the class, and which, conversely, have left the barnacles and sacculinas, through the action of degenerative changes, among the groundlings of the group.

The assumption of a sedentary life, whether parasitic in nature like that of sacculina, or whether it is represented by mere attachment and fixation to some inorganic thing, as in the case of the barnacles, is therefore seen to operate in the direction of producing degeneration of the animal's constitution. The tendency of such habit is toward simplification of structure and not toward that progressive advance and evolution which, in the case of the higher crustacean races, have evolved from the relatively simple "nauplius" of the past the crabs, lobsters, shrimps, and prawns of to-day.—Gentleman's Magazine.

[To he continued.]