Popular Science Monthly/Volume 63/August 1903/The Bird Rookeries on the Island of Laysan

| THE BIRD ROOKERIES ON THE ISLAND OF LAYSAN.[1] |

By Professor C. C. NUTTING,

STATE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA.

PERHAPS the most interesting experience enjoyed by the naturalists of the U. S. S. Albatross during her recent Hawaiian cruise was a visit to Laysan, an island situated almost in mid Pacific, about eight hundred miles to the west and a little to the north of Honolulu.

As viewed from the anchorage, a more uninteresting bit of land could hardly be found, there being nothing in view  Fig. 1. Like Great Brown Goslings, balanced on their heels, with their toes in the air. save a stretch of coral sand beach surmounted by low bushes and relieved by a wooden light-house and the sheds of the guano company that leases the island. On the morning of our arrival the surf was the worst seen during the entire cruise. Nowhere did there appear to be a spot where the heavy swell did not break in thundering roars, and the rollers appeared to be at least twenty feet high. One of our party succeeded in making a landing in a small boat manned by Japanese, and thus secured a day with the camera ashore on the far-famed island of Laysan, and the experience was one not soon to be forgotten.

Fig. 1. Like Great Brown Goslings, balanced on their heels, with their toes in the air. save a stretch of coral sand beach surmounted by low bushes and relieved by a wooden light-house and the sheds of the guano company that leases the island. On the morning of our arrival the surf was the worst seen during the entire cruise. Nowhere did there appear to be a spot where the heavy swell did not break in thundering roars, and the rollers appeared to be at least twenty feet high. One of our party succeeded in making a landing in a small boat manned by Japanese, and thus secured a day with the camera ashore on the far-famed island of Laysan, and the experience was one not soon to be forgotten.

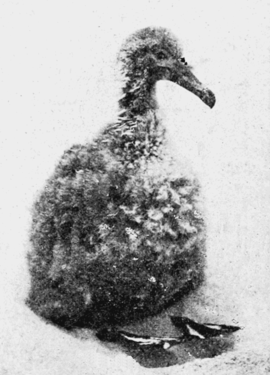

The road to the main albatross rookery is of the same white coral sand that covers almost the whole island. The glare is exceedingly trying to the eyes, and the heat would be oppressive to one who found time to think of it. Birds are everywhere, and so tame that they actually have to be shoved aside with the foot. The road was dotted with the young of the white albatross, with a sprinkling of adults. The youngsters were but three months old, although fully as large as the adults, covered with brownish down, except on the breast where the white permanent feathering had in most cases been acquired. Their appearance is ludicrous beyond description, reminding one of great brown goslings sitting upright, balanced on their heels with their toes in the air. Upon being approached they make no attempt whatever to escape, but straighten up as if about to give a military salute and snap their mandibles together with great rapidity, making a rattling noise amusing at first, but annoying after a few thousand repetitions. Occasionally they resented the intruding foot and vomited a quantity of half-digested food, a most disgusting mess, over the trouser leg of the visitor.

The scene at the main rookery is beyond description. Here are acres and acres of level ground worn bare of vegetation and literally covered with albatrosses. At the time of our visit probably four out of five were young birds born the preceding February, although adults are everywhere sprinkled among them. Although the vast majority are of the white species, there are a few sooty albatrosses which generally prefer the u])per levels of the beaches. Of course all these youngsters have to be fed, and at any given time most of the adults are at sea fishing for sustenance for their rapidly growing and voracious progeny. So far as we could ascertain this food consisted almost exclusively of squid. The stomachs we dissected contained squid and nothing else, and the only solid excrement was the eyes and beaks of these animals. Mr. Schlemmer, manager for the guano company, estimates that about two million albatrosses make their home on Laysan, and one can well believe it. Although aggregated most densely at the rookery, these birds are everywhere on the island, which is

in the shape of a rude quadrilateral about two by one and three fourths miles in area. Albatrosses are scattered everywhere, except on the tide

washed beaches and on the central lagoon. They are crouching under the shade of almost every bush and tuft of grass. The most conservative estimate of the necessary food supply yields almost incredible results. Cutting Mr. Schlemmer's estimate in two, there would be 1,000,000 birds, and allowing only  Fig. 5. Downy Young of White Albatross. half a pound a day for each, surely a minimum for these large, rapidly growing birds, they would consume no less than 250 tons daily.

Fig. 5. Downy Young of White Albatross. half a pound a day for each, surely a minimum for these large, rapidly growing birds, they would consume no less than 250 tons daily.

The young birds do not appear to move about much, otherwise the parents would have difficulty in locating them when bringing food, and one can not but wonder how each finds its particular progeny among the hundreds of thousands that appear exactly alike to the human eye. Both parents assist in the labor of feeding the young, a most interesting process. When the parent alights near the young bird the latter begins to beg energetically by gesture, for they are silent as a rule, crouching before the old bird and working the head backward and forward in urgent appeal. Then the youngster grasps the bill of the adult, holding it crosswise, but at an acute angle, when the partly macerated food is squirted with unerring aim right down the throat of the feeding bird, apparently without the loss of a drop. This process is repeated again and again until the parent has literally pumped itself dry.

Here and there are small groups of adults engaged in a sort of play that may be a continuation of the courtship antics, a most laughable performance. The birds commence  Fig. 6. Sooty Albatross Feeding Young. by walking around each other in a sort of 'cake-walk' with a peculiar swagger suggestive of the 'bowery boy' in his glory. Then they snap their mandibles together with amazing rapidity, making a rattling resembling the drumming of the woodpecker. Again they stand upright, facing each other, and put their bills under their wings 'as if hunting for a cigar,' as suggested by one of our officers. Next they stretch their necks upward with bills pointed heavenward, uttering a long-drawn 'ah-h-h-h-,' with a rising inflection. This play is repeated indefinitely, and with variations, and when, as

Fig. 6. Sooty Albatross Feeding Young. by walking around each other in a sort of 'cake-walk' with a peculiar swagger suggestive of the 'bowery boy' in his glory. Then they snap their mandibles together with amazing rapidity, making a rattling resembling the drumming of the woodpecker. Again they stand upright, facing each other, and put their bills under their wings 'as if hunting for a cigar,' as suggested by one of our officers. Next they stretch their necks upward with bills pointed heavenward, uttering a long-drawn 'ah-h-h-h-,' with a rising inflection. This play is repeated indefinitely, and with variations, and when, as

sometimes happens, it is accomplished in perfect unison, the effect is extremely laughable.

The life history of the albatrosses on Laysan, as given us by Mr. Schlemmer, is as follows: The eggs are laid late in January or early in

February, both parents taking part in incubation. The nest is made by the female by merely scraping together the earth or mud wherever she is resting and building it into an elevated ring within which her single egg is deposited. The young are hatched late in February,

usually, and both parents are kept busy from that time until fall in providing food for the little ones. By the latter part of September the young fully attained their adult plumage and are capable of sustained flight. Then the whole great host takes wing into the unknown, literally so; for, so far as I can learn, this species, Diomedea immutabilis Roth, absolutely disappears from human ken for about two months of each year. There seems to be some evidence that it betakes itself to the Arctic seas. The apparent obliteration of this  Fig. 11. Hovering with Graceful Poise like Immense White Butterflies. vast swarm of birds for a definite period annually is a mystery still to be solved. In November the birds arrive at Laysan as suddenly as they departed, and at once begin to prepare for domestic responsibilities. During the ten months annually spent there they do not appear to wander far from their breeding grounds. Indeed our vessel did not encounter them so far to the eastward as the main Hawaiian group.

Fig. 11. Hovering with Graceful Poise like Immense White Butterflies. vast swarm of birds for a definite period annually is a mystery still to be solved. In November the birds arrive at Laysan as suddenly as they departed, and at once begin to prepare for domestic responsibilities. During the ten months annually spent there they do not appear to wander far from their breeding grounds. Indeed our vessel did not encounter them so far to the eastward as the main Hawaiian group.

Great as is the multitude of albatrosses and conspicuous as they are on account of their size, the terns of five or six species greatly exceed them in number, probably forming more than half of the entire bird population of the island. The clamor that greets the intruder in one of these immense tern rookeries is simply appalling, the air fairly quivering with their ear-splitting shrieks as they circle in clouds around his head and dash savagely directly at his face in their fierce endeavor to drive him away. There were probably hundreds of bushels of eggs of these birds  Fig. 12. Rookery of 'Love Birds.' at the time of our visit. The most numerous terns are the 'black-backed' and 'gray-backed' wideawakes, of which there must be millions, nesting among the bushes and tufts of grass, particularly on the southern end of the island. The vegetation grows right in the dazzling white coral sand, which appears as white as snow in the photographs.

Fig. 12. Rookery of 'Love Birds.' at the time of our visit. The most numerous terns are the 'black-backed' and 'gray-backed' wideawakes, of which there must be millions, nesting among the bushes and tufts of grass, particularly on the southern end of the island. The vegetation grows right in the dazzling white coral sand, which appears as white as snow in the photographs.

One of the most exquisitely beautiful birds that the writer has ever seen is a small tern known locally as the 'love bird,' pure white with large black eyes and bill. They have the habit of hovering with graceful poise over the intruder, like immense white butterflies, silently inspecting one as if impelled by a mild curiosity rather than resentment, the actuating motive of the other terns. There are many small rookeries of these beautiful creatures scattered over the island; one in particular is in a very picturesque rocky nook at the south end.

Two species of noddy terns are abundant, and much alike, except in size, being sooty brown with a grayish white cap.

Large colonies of man-o-war birds were nesting on the tops of low bushes. These are among the most accomplished and graceful fliers of all the avian world, and have the habit of soaring with extended wings for hours at a time. The males have an inflatable air-sack under the throat which can be distended at will into a great red pensile bag, resembling both in color and size the red toy balloons in which  Fig. 15. Young of Shearwater showing Protective Coloration.children delight. These birds are probably the most inveterate thieves and pirates of all the feathered tribe, robbing other birds of their fish, and even making them disgorge for the benefit of their persecutors. They lay a single white egg, and young in all stages of development were numerous. When the rookery was disturbed the incubating birds, both male and female, reluctantly left their eggs or young, in some instances carefully depositing a fish beside the young before leaving. Afterward, greatly to our surprise, they would swoop down, actually grazing our faces with their wings, and deftly seize a nestling by the head and make off with it, circling around high in air, finally dropping it to the ground, where it was eventually devoured. We could not

Fig. 15. Young of Shearwater showing Protective Coloration.children delight. These birds are probably the most inveterate thieves and pirates of all the feathered tribe, robbing other birds of their fish, and even making them disgorge for the benefit of their persecutors. They lay a single white egg, and young in all stages of development were numerous. When the rookery was disturbed the incubating birds, both male and female, reluctantly left their eggs or young, in some instances carefully depositing a fish beside the young before leaving. Afterward, greatly to our surprise, they would swoop down, actually grazing our faces with their wings, and deftly seize a nestling by the head and make off with it, circling around high in air, finally dropping it to the ground, where it was eventually devoured. We could not

determine whether the parents actually destroyed their own young or not, but it is probable that this revolting form of cannibalism must be added to the other crimes charged to their account.  Fig. 17. Tropic Bird on Nest. Not only does the bird fauna crowd all the available space on the ground, and in the bushes, and swarm in the air above, but still another vast multitude burrows under the sandy surface, forming a subterranean population that in itself would make the island of peculiar interest to the naturalist. Nor does the human visitor long remain in ignorance of this fact, for he has taken but a few steps anywhere among the bushes before lie suddenly joins the 'submerged tenth' in a most undignified and

Fig. 17. Tropic Bird on Nest. Not only does the bird fauna crowd all the available space on the ground, and in the bushes, and swarm in the air above, but still another vast multitude burrows under the sandy surface, forming a subterranean population that in itself would make the island of peculiar interest to the naturalist. Nor does the human visitor long remain in ignorance of this fact, for he has taken but a few steps anywhere among the bushes before lie suddenly joins the 'submerged tenth' in a most undignified and  Fig. 18. 'Bush Gannet' on Nest. precipitate manner, and is struggling waist deep in the yielding sand, an unwelcome invader of the home of the shearwater. This experience has the charm of novelty at first, but becomes exasperating after a score of repetitions in the course of an hour, with the perspiration streaming down one's face and the sand packed inside of one's shoes and clothing. How many scores or hundreds of thousands of these burrowing Procellaridæ there are on the island it is vain to estimate; but there are four or five species, and the entire surface is fairly undermined by their tunnels

Fig. 18. 'Bush Gannet' on Nest. precipitate manner, and is struggling waist deep in the yielding sand, an unwelcome invader of the home of the shearwater. This experience has the charm of novelty at first, but becomes exasperating after a score of repetitions in the course of an hour, with the perspiration streaming down one's face and the sand packed inside of one's shoes and clothing. How many scores or hundreds of thousands of these burrowing Procellaridæ there are on the island it is vain to estimate; but there are four or five species, and the entire surface is fairly undermined by their tunnels  Fig. 19. 'Sand Gannet' with Egg and Young. and burrowings. Their notes are melancholy beyond expression, being a distressful moaning, sometimes reminding one of the less romantic yowling of the night wandering cat.

Fig. 19. 'Sand Gannet' with Egg and Young. and burrowings. Their notes are melancholy beyond expression, being a distressful moaning, sometimes reminding one of the less romantic yowling of the night wandering cat.

As one walks among the bushes be is from time to time greeted with most strident and piercing screams from nesting tropic birds, rarely beautiful creatures, pure satiny white, the wings and tail mainly black, the two central tail feathers being excessively elongated and bright red. When nesting these birds are so well concealed that they would he unnoticed were it not for their strident outcries. This resulted in distressful experiences when the 'jackies' from the Albatross were given shore leave, and went around pulling the tail feathers from every tropic bird they could find; the birds refusing to leave the nests, but protesting vigorously and occasionally getting revenge by biting savagely with their powerful beaks.

The gannets are among the more conspicuous birds of the island, being large white birds with black wings. They are known as 'bush

gannet' and 'sand gannet,' names indicative of their nesting habits. The downy young of these birds are exquisitely white and fluffy, reminding one of animated puff balls.

The Laysan duck, curlews, plover and turn-stones are found in numbers along the margin of the central lagoon, and furnish a welcome addition to the larder of Mr. Schlemmer and the men in his employ. Four species of land birds complete the list. One is the 'wingless rail,' not literally wingless, but with wings reduced to functionless rudiments.

Another species confined to this limited area is the Laysan finch, a large sparrow with yellow head and under surface and a rich sprightly song; and the last is the 'Laysan honey-eater,' a minute form with body and head rich, dark red, abundant among some shrubs with red blossoms growing near the lagoon.

Of course any estimate of the bird population of this remarkable island is little better than guess-work, but it seems safe to say that at least six or eight million make their home on this small atoll in mid Pacific, the total area of which, including the lagoon, is only about three and one half square miles. I know of no more dense population anywhere, although it may possibly be matched on some of the islands in the Alaskan region. But there a vast majority of the birds leave during the winter, while at Laysan nearly all remain at least ten months of the year.

Much of interest could be said concerning the guano deposits and the operations of the company that leases the island. Thousands of tons are exported annually, and it is entirely possible that this valuable fertilizer is now being deposited as rapidly as ever it was, owing to the wise policy of not disturbing the birds that is rigidly enforced by the company. The excrement is almost entirely fluid, and gradually saturates and fills the thin soil and porous coral rock, thus making the 'guano' of commerce. Strangely enough there is no very perceptible odor, even at the rookery.

The naturalists of the Albatross spent a week in studying the fauna and flora of this exceedingly interesting island, while the naval officers made a complete map, including a chart of the reefs near the anchorage. Here are found unexcelled conditions for collecting and studying the life histories of birds. All the species are very abundant, and can be seen in a day's visit. Every species can be caught, either in the hand or with a hand-net, and mercifully killed with chloroform without mutilation or blood-stains. They can all be studied at leisure, and at close range. The photographer finds himself in a veritable paradise, able to set up his camera at any desirable distance, even to 'pose' his subjects to suit his fancy, and take pictures of birds, nests and young to his heart's content.

It is simply delightful to find one spot, at least, in this world of ours where the birds are not afraid. So long as the guano holds out, these conditions will probably remain unchanged. If this time comes to an end, the government should see to it that this wonderful preserve of avian life is protected from the ravages of man, the destroyer, and of the rapidly diminishing moiety of his better half that still persists in the aboriginal feather-wearing habit.

- ↑ Published with the permission of Hon. George M. Bowers, U. S. Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries.