Popular Science Monthly/Volume 70/June 1907/The Problem of Age, Growth and Death I

THE

POPULAR SCIENCE

MONTHLY

JUNE, 1907

| THE PROBLEM OF AGE, GROWTH AND DEATH.[1] |

By CHARLES SEDGWICK MINOT, LL.D., D.Sc.

JAMES STILLMAN PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE ANATOMY IN THE HARVARD MEDICAL SCHOOL.

I. The Condition of Old Age

THE subject of age has ever been one which has attracted human thought. It leads us so near to the great mysteries that all thinkers have contemplated it, and many are the writers who from the literary point of view have presented us, sometimes with profound thought, often with beautiful images connected with the change from youth to old age. We need but to think of two books familiar more or less to us all—that ancient classic, Cicero's De Senectute, the great book on age, one might almost say, from the literary standpoint, and that of our own fellow-citizen, my former teacher and professor at the Medical School, Dr. Holmes, who in his delightful 'Autocrat' offers to us some of his charming speculations upon age. From the time of Cicero to the time of Holmes numerous authors have written on old age, yet among them all we shall scarcely find any one who had title to be considered as a scientific writer upon the subject. Longevity is indeed a strange and difficult problem. Many of you doubtless have had your attention directed recently to the republished translation of Connaro's famous work and know how sensible that is, and as you read it you must have perceived how little in the practical aspect of the matter we have passed beyond the advice which old Connaro gave to us. And yet silently in the medical laboratories, and in the physiological and anatomical institutes of various universities, we have been gathering more accurate information as to what is the condition of persons who are very old.

We know, first of all, from our common observation, that the very old grow shorter in stature. We see that they are not so tall as in the prime of life. The figures which have been compiled upon this subject are instructive, for they show that at the age of some thirty years the average height of men—these figures refer to Germans—is 174

centimeters. It remains at that, however, only for a short period; then it decreases and at forty it is already less; at fifty decidedly less; and at sixty the change has become more marked; until at seventy years we find that the height has shrunk from 174 to 161. There it remains, or thereabouts, through the remainder of life, though there may be a small further diminution. This decrease in stature is due largely to the changes in the vertebral column. First of all there is a stoop. The vertebral column is, to be sure, never straight, but in old age it becomes more curved, and the result is a falling of the total stature. But this is not the chief cause, for in addition to this the

softer cartilages and elements of the spinal column become harder, change into bone, and as that change occurs they acquire a less extent and become smaller, and the result is that the vertebral column as a whole collapses somewhat and thus increases the diminution of height. We find, as we look at the old, a great change to have come over the face. The roundness of youth has departed; the cheeks are sunken; the eyes have fallen far back; the lips are drawn in. All of these changes indicate to us, when we think upon them, the fact that there has been a certain shrinkage and shrivelling of that which is within and beneath the skin. Expressed in technical terms, we should call this an atrophy, and to anatomists the mere sight of the face of a very old person reveals at once this fundamental fact of an atrophy of the parts, an actual loss of some of their bulk, which is one of the most characteristic and fundamental marks of old age. The gait becomes shuffling, the foot is no longer lifted free from the ground, as the old man walks along. He does not rise upon his toes, but the sole of the foot is kept nearly flat and as he drags it cumbrously forward it is apt to strike upon the sidewalk. This indicates to the physiologist a lessened power in the muscles, a lessened control over the action of these muscles, an inferior coordination of the movements, so that there has been in the old man, judged by his gait alone, a physiological deterioration as well as an anatomical atrophy. You notice too his slow speech, often difficult hearing, and imperfect sight. All of these qualities show a loss, and we commonly think of the old as those who have lost most, who have passed beyond the maximum of development and are now upon the path of decline, going down ever more rapidly. One of the chief objects at which I shall aim in this course of lectures will be to explain to you that that notion is erroneous, and that the period of old age, so far from being the period of true decline, is in reality essentially the period in which the actual decline going on in each of us will be least. Old age is the period of slowest decline—a strange, paradoxical statement, but one which I hope to justify fully by the facts I shall present to you in this course. In the old person you note that there is in the mind some failure and also loss of memory—less mental activity, greater difficulty in grasping new thoughts, assimilating new ideas, and in adapting himself to unaccustomed situations. All this betokens again the characteristic loss of the old. And as we turn now from these outward investigations to those which the anatomist opens up to us, we learn that in the interior of the body, and in every organ thereof, the species of change which I have referred to as characteristic of the very old, is going on and has become in each part well marked. Let us first examine the skeleton. In youth many parts of the skeleton are soft and flexible, like the gristles and cartilages, which join the ribs to the breastbone, but in the old man they are replaced by bone. Bone represents an advance in organization, in structure, as we say, over the cartilage. The old man has in that respect progressed beyond the youthful stage; but that progress represents not a favorable change; the alteration in structure from elastic cartilage to rigid bone is physiologically disadvantageous, so that though the man has progressed in the organization or anatomy of his body, he has really thereby rather lost than gained ground. Indeed in the skeleton this principle of loss is already revealing itself. In the interior of the bones of the arms, of the legs, we find a spongy structure, bits of bone bound together in many different directions, as are the spicules or fibers in a sponge, and by being bound so together they unite lightness with strength. As you know a column of metal, if hollow, is stronger than the same amount of metal in the form of a rod. So with the bones. If they have this spongy structure, if their interiors are full of little cavities with intervening spicules acting as braces in every direction, then they acquire great strength with little material. Now in the old the internal spongy structure is dissolved away and there is left only a hard external shell. Partly on this condition depends the greater liability of the bones in the old person to break. If we examine the muscles we see that they have become less in volume, and when we apply the microscope to them we see that the single fibers on which the strength of the muscles depends have become smaller in size and fewer in number.[2] The muscle has actually lost; it is inferior, physiologically speaking, to what it was before. You remember how melancholy Jacques reminded us of this fact in speaking of the hose 'a world too wide for his shrunk shank.' His saying is justified by the loss of the muscles in volume and strength. The same phenomenon of atrophy shows itself in the digestive organs. Those minute structures in the wall of the stomach by which the digestive juice is produced, undergo a partial atrophy, in consequence of which they are less able to act; they are not so well organized, therefore, not so efficient as in earlier stages. The lungs become stiffened; the walls which divide off an air cavity from the neighboring air cavities do not remain so thin as in youth, but become thickened and hardened, and the vital capacity of the lungs, that is to say the capacity of the lungs to take in and hold air, is by so much lessened. The heart— it seems curious at first—is in the old always enlarged; but this does not represent a gain in real power. On the contrary, if we study carefully the condition of the circulation of the blood in the old, we find that the walls of the large blood-vessels, which carry the blood from the heart and distribute it over all parts of the body—vessels which we call arteries—have lost the elastic quality which is proper to them and by which they respond favorably to the pumping action of the heart. Instead they have become hard and stiff. We call this by a Greek term for hardening, sclerosis, and arterial sclerosis is one of the most marked and striking characteristics of old persons. Now when the arteries become thus stiffened, it requires a greater force and greater effort of the heart to drive the blood through them, and in response to this new necessity, the heart becomes enlarged in an effort of the organism to adapt itself to the new unfavorable condition of the circulation established by age. But the power of the heart becomes inferior along with this hypertrophy or enlargement, and we see that in the old, in order to make up for the feebleness of the enlarged heart, it beats more frequently. In other words, the pulse rate in the old person increases.[3] We find, for instance, that at the time of

| Age | Mean Frequency |

Age | Mean Frequency |

Age | Mean Frequency |

| 0-1 | 134 | 13-14 | 87 | 25-30 | 72 |

| 1-2 | 111 | 14-15 | 82 | 30-35 | 70 |

| 2-3 | 108 | 15-16 | 83 | 35-40 | 72 |

| 3-4 | 108 | 16-17 | 80 | 40-45 | 72 |

| 4-5 | 103 | 17-18 | 76 | 45-50 | 72 |

| 5-6 | 98 | 18-19 | 77 | 50-55 | 72 |

| 6-7 | 93 | 19-20 | 74 | 55-60 | 75 |

| 7-8 | 94 | 20-21 | 71 | 60-65 | 73 |

| 8-9 | 89 | 21-22 | 71 | 65-70 | 75 |

| 9-10 | 91 | 22-23 | 70 | 70-75 | 75 |

| 10-11 | 87 | 23-24 | 71 | 75-80 | 72 |

| 11-12 | 89 | 24-25 | 72 | 80 and over79 | |

| 12-30 | 88 | ||||

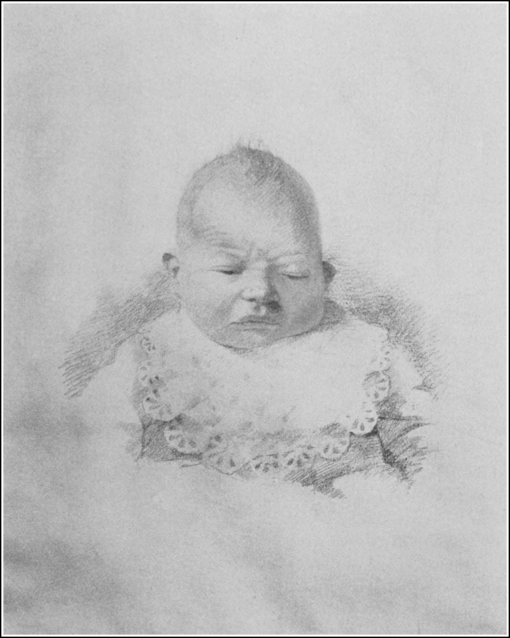

birth the pulse rate is at the rate of 134 beats to a minute. It rises slightly during the first three months of infancy until at the end of the third month it reaches some 140 beats a minute; it soon falls off, however, and at the end of the first year it has sunk to 111; at five or six years it becomes 98, and at twenty-one years it has sunk to 71 or 72. There are thereafter certain minor fluctuations in the rate of the heart-beat with advancing age, but generally it may be said that this value of 72 beats a minute is characteristic of adult life. But when a person becomes eighty years old, it has been found that upon the average the rate of the heart-beat rises and becomes 79 a minute. Hence it is clear that though the heart is larger, it has to make a greater effort, that is to say a more frequent beat, in order to maintain the necessary circulation of the blood. We see also, as we go back to the anatomical examination of the body, that those important structures which we call the germ cells, upon which the propagation of the race depends, which present under the microscope certain clearly recognized characteristics by which they can be distinguished from all other cells of the body, that these germ-cells cease their activity altogether in the very old, and one of the great functions of life is thus blotted out altogether from the history of the individual.

Turning now to the yet nobler organs, especially the brain, we see a curious change going on, a change of which old age presents to us the culminating record. In order to study the weight of the brain, it is necessary to compare people of the same size, for the size and weight of the brain depend somewhat upon the size of the individual. Now it has been discovered by careful examination of persons of similar size that the brain begins relatively early to diminish its weight. Thus in persons of a height of 175 centimeters, and over, of the male sex, it is found that in a period of from twenty to forty years the brain weight is 1,409 grams. But from forty-one to seventy years it has sunk to 1,363, and in persons of from seventy-one to ninety it has shrunk to 1,330. Women of corresponding size are not easily found, and a more average height for women is 165 centimeters; a woman of such a height is likely to have—among the white races, be it always understood—a weight of brain of 1,265 grams, at forty to seventy years a brain of 1,200, and at seventy-one to ninety years a brain of only 1,166 grams.[4]

I give these figures because they show that there is no guessing, but a definite, positive knowledge, proving that soon after the maturity of life in the individual is reached, the shrinkage of the brain begins, and then continues almost steadily to the very end of life.

It is not only the anatomist, but it is perhaps almost equally the physiologist who gives us insight into the changes, which go on in the old. I spoke a few moments ago of the pulse rate, and of the change which that offers. At first sight it seems as if a greater pulse rate indicated an improvement, but if you recall the explanation which I have given you, you will acknowledge that this is by no means an acceptable interpretation, but that on the contrary the change is a clear mark of enfeeblement. In the respiration, also, we observe a like change. Here the comparison is not quite so easy as we should at first imagine, because there is a relation between the size of the individual and the respiration. The respiration, as you all know, frees the body from the products of combustion, particularly from that product which we know as carbon dioxide. The result of the combustion going on in the body (which in its end term appears to us as carbon dioxide expelled from the lungs) is to produce heat, to develop the necessary warmth for the maintenance of the proper temperature of the body. Now in the very young the bulk of the body is not great, but the loss of heat is very great, and this perhaps can be most readily explained to you if you imagine that you hold in one hand a very small potato and in the other a very large potato, both of which have come at the same moment from the same oven, and that you have just started out for a cold winter drive. You all know, of course, that in a little while the small potato, though it was as hot as the large one at first, will have lost its heat, will no longer serve to keep the hand warm, but the other hand, in which the bulkier potato is held, in which the volume of the heat—we might so express it, perhaps—is correspondingly great, benefits by the retained heat a long time. Essentially similar to this is the difference between the child and the adult. The child loses heat with comparatively great rapidity—the old person at a comparatively slow rate. Hence it is necessary for the child to produce more warmth in order to keep up the natural normal temperature of the body. When, therefore, we find that in the old person the respiration is diminished, and that the production of carbon dioxide from the lungs is greatly lessened, we are not immediately to jump at the conclusion that the quality of physiological action has been debased—that we see here a sign of decrepitude. On the contrary, the change is the result of physiological adaptation, of suiting the performance of the body to its needs. This is one of the great wonders, one of the mysteries of life, of which we here have a sample, the constant adaptation of the means to the end. That which the body needs is done by the body. A child needs more warmth, and its body produces more; the old person needs less warmth, and his body produces less. How this is accomplished we are unable to say, but constantly we see evidence of this purposeful accommodation on the part of the body—what is called by the physiologists the teleological principle, the adaptation of the reaction of the body to its needs. There are innumerable illustrations of this, many of which are of course perfectly familiar to us, although perhaps we do not think of them as illustrations of this great law of nature. As, for instance, when we eat a meal, and the presence of food in the stomach calls into action the glands in the wall of the stomach by which the digestive juice is secreted. The juice is produced exactly at the time when it is needed. Innumerable, indeed, are the illustrations of this fundamental principle.

There is another class of phenomena characteristic of the very old which will perhaps seem a little surprising to you after the general tenor of my previous remarks. I refer to the power of repair. This, modern surgery especially has enabled us to recognize as being far greater in the old than we were wont to assume; and we know that there is a certain luxury, a certain excess reserve in the power of repair, and that we may go far beyond the ordinary necessities of our life in our demands upon our organism, and still find that our body, is capable of making the necessary response. Ordinarily the amount of blood which we require is moderate in amount—moderate in the sense that the destruction of the blood continually going on in the body is not a very rapid process; but if, through some accident, a person loses a large quantity of blood then by one of these teleological reactions of which I have spoken, the production of new blood is increased, the loss is soon made up, and we discover that the blood, so to speak, has been repaired. Or when a little of the skin is lost, it quickly heals over. That again is due to the power of repair. Ordinarily so long as the skin remains whole that power is not called into action, but if a wound comes, then the regenerative force resident always in the skin, but inactive, comes into play and produces the mending which is such a comfort. So in old people, some of this luxury of reparative power persists, so that they can recover from wounds in a far better way than we should imagine if we judged them only by the general physiological and anatomical decline exhibited throughout all parts of the body. Some of the luxury of repair comes in usefully in old age. Now if we consider all these changes in the most general manner, we perceive that they are clearly of one general character; they imply an alteration in the anatomical condition of the parts; but it is an alteration which does not differ fundamentally in kind from the alterations which have gone on before, but it does differ in the extent and in part in the degree to which these alterations have taken place. When the elastic cartilaginous rib becomes bony, nothing different is happening from that which happened before, for there was a stage of development when the entire rib consisted of cartilage, and in the progress of development toward the adult condition that cartilage was changed gradually into bone, thus producing the characteristic, normal, efficient bony rib of the adult. When old age intervenes, the change of the cartilage into bone goes yet further, but it progresses in such a way that it is no longer favorable, but unfavorable. We have then in this case a clear illustration of a principle of change in the very old which is, I take it, perhaps sufficiently well expressed by saying that the change which is natural in the younger stage is in the old carried to excess. But there is in addition to this, something more, of which I have already spoken, namely the atrophy of parts, and by atrophy we mean the diminution, the lessening of the volume of the part. There is a partial atrophy of the brain in consequence of which that organ becomes smaller; there is an extensive atrophy of the muscles in consequence of which their volume is diminished, and their efficiency decreased. Atrophy is preeminently characteristic of the very old, and we see in very old persons that it becomes each year more and more pronounced. Indeed, it has been said recently by Professor Metchnikoff, a distinguished Russian zoologist, now connected with the Pasteur Institute in Paris, some of whose publications many of you have doubtless read, that his conception of the nature of senility, of old age, could best be expressed in a single word, atrophy. "On résume la senilité par un seul mot: atrophie."[5] That is his estimate of old age. But that is not the only estimate of old age which has been made up to the present time. We find one, which is much more prevalent, is that which connects it with the condition of the arteries. Indeed, Professor Osier has written this sentence—"Longevity is a vascular question, and has been well expressed in the axiom that a man is only as old as his arteries." Now these are medical views, not biological, and you will find that there is a very extensive literature dealing with old age in man based upon the conception that old age is a kind of disease, a chronic disease, an incurable disease. Medical writers have put forward various conceptions giving a medical interpretation of this disease. That to which I just referred is the favorite one, the one you are most likely to hear from physicians to-day—namely, the theory of arterial sclerosis, that the hardening of the walls of the arteries is the primary thing; it interferes with the circulation, the bad circulation interferes with the proper working of every part of the body, and as the circulation becomes impeded, various accessory results are produced in the body in consequence. It is brought to a lower or more diseased condition than before. And so they interpret sclerosis of the arteries as the primary thing, because they can trace so many alterations in the old which resemble diseased alterations, to these natural changes in the arteries by which they acquire hardened and inelastic walls, which prevent the proper response of the artery to the heart beat, upon which the normal healthy circulation largely depends. Another interpretation, very curious and interesting, is that which has been recently offered by the same Professor Metchnikoff whom I have just mentioned. He has written a book upon the 'Nature of Man,' translated in 1903, and published in this country. It is an interesting book. It gives a most attractive picture, incidentally, of Metchnikoff himself, a man of pleasantly optimistic temperament, but a man thoroughly imbued with the spirit which has so often been attributed to contemporary scientific men, of cold, intellectual regard towards everything, towards life, towards man, towards mystery. For him mysteries of all sorts have little interest. Those things which are mysterious are beyond the sphere of what can hold his attention. He must reside in the clear atmosphere of definite, positive fact. This mental bias is shown in his book. He reviews in a happy way various past systems of philosophy; he describes various religions; and he points out his reasons for thinking that all of these are insufficient, that there is no satisfaction to be derived from any of the ancient philosophies or from any of the great world religions. Nevertheless he is an optimist. He has noticed as a result of his meditations upon the arrangements within our bodies that we suffer very much from what he calls disharmonies, by which he means imperfect adaptations of structures within us to the performance of the body as a whole. He mentions various instances of such disharmonious parts. They do not seem to me quite so imposing as apparently they do to him, for many of his disharmonies are based upon the fact that we do not know that a certain structure or part has any useful rôle to play in the body. But I am inclined to suspect that in many cases it is only because we are ignorant; the list of useless structures in the human body was a few years ago very long; it has within recent years been greatly shortened, and we should learn from this experience a caution in regard to judging about these things, which, I think, Professor Metchnikoff has failed to exert duly in forming his opinions on these disharmonies. Now among the disharmonies which he recognizes is that of the great size of the large intestine, which is of such a caliber that a considerable quantity of partially digested food can be retained in it at one time. When such food is retained in the intestine, it may undergo a process of fermentation. There are many sorts of fermentation, and some of them produce chemical bodies which are injurious to the human organism. Bacteria, which will cause fermentation of this sort, do actually occur in the human intestine. Metchnikoff thinks that, as we grow old, this tendency to fermentation increases. Now the bodies produced by fermentation, the chemical bodies, I mean, get into our system and poison us. The result of the poisoning is that the native capacities of the various tissues and organs of the body are lowered, as happens in a man 'intoxicated.' All parts of a man may be poisoned, not necessarily always with alcohol, but with many other things as well, and such a poisoning Professor Metchnikoff assumes to result from intestinal fermentation. Moreover, he has further observations, which lead him to the idea that certain cells go to work upon the poisoned parts and do further damage. The cells in question are minute microscopic structures, so small that we can not at all see them with the naked eye, but which have a habit of feeding in the body upon the various parts thereof whenever they get a chance. Cells of this sort go by the scientific name of phagocytes, which is merely a Greek term for 'eating cells.' The phagocytes, for instance, devour pigment in the hair, and in old persons the production of white hair has resulted from the activity of phagocytes which have eaten the pigment which should have remained in the hair and kept its color. But the pigment of the hair is not the only thing they will attack; they will make their aggressive inroads upon any part of the body; and Professor Metchnikoff has advanced the theory that old age consists chiefly in the damage which is done by phagocytes to poisoned parts of the body, the poisoning being due to the fermentation in the large intestine. Now it has been observed by some of the German investigators of these matters that the presence of lactic acid interferes with this fermentative process as it goes on in the intestine. Lactic acid, as its name implies, is the characteristic acid which occurs in milk when it becomes sour. An Italian friend of Professor Metchnikoff tried drinking some sour milk with the idea of stopping the fermentation in the intestine, and so putting an end to the deleterious change, and he believes in the short time that he tried it that it did him good—quite, you see, in the way of a patent medicine. Professor Metchnikoff, on this basis, has recommended, in his book on the 'Nature of Man,' the regular drinking of sour milk, in the hope apparently that that will postpone senility, and will leave us our powers in maturity long beyond that period when we at present reach the fullness of our vigor, and advance the period of time when the changes of the years put us out of court. He regards this as an optimistic substitute for the various forms of philosophy and religion which many millions of people have found helpful in life, and certainly it is the cheapest substitute which has ever been seriously proposed.

There is another writer who, though having a German name, is in reality a Russian, Professor Mühlmann. He has another theory in regard to the fundamental nature of senility. He takes such instances as that which I spoke of, of respiration in connection with the production of warmth in the child's body and in the body of the adult, and finds that the diminution of the surface in proportion to the bulk of the body is characteristic of the old, and he concludes that we become old because we do not have proportionately surface enough left. His view implies, apparently, that if we could keep ourselves more or less of the stature of pygmies we should be healthier and better off. I confess these theories, and many others which I might enumerate to you, seem to me to be somewhat fantastic—odd rather than valuable. Yet they all spring from this one common feeling, which is, I believe, a sinister influence upon the thought of the day, in regard to the problem of age—they spring from the medical conception that age is a kind of disease, and that the problem is to explain the condition as it exists in man. Now that is precisely what I wish to protest against. What I hope to accomplish in these lectures is to build up gradually in your minds some acquaintance with the fundamental and essential changes, which are characteristic of age and in regard to which we have been learning something during the last few years—-I might almost say only within recent years—and by means of this exposition to give you a broader view and a juster interpretation of the problem. I hope, before I finish, to convince you that we are already able to establish certain significant genaralizations as to what is essential in the change from youth to old age, and that in consequence of these generalizations, now possible to us, new problems present themselves to our minds, which we hope really to be able to solve, and that in the solving of them we shall gain a sort of knowledge, which is likely to be not only highly interesting to the scientific biologist, but also to prove, in the end, of great practical value. Surely we can not hope to obtain any power over age, any power over the changes which the years bring to each of us, unless we understand clearly, positively and certainly, what these changes really are. I think you will learn, if you do me the honor to follow the lectures further, that the changes are indeed very different from what we should expect when we start out on a study of age, and that the contributions of science in this direction are novel and to some degree startling. We can begin to approach this broader view of our subject if we pass beyond the consideration of man.

If we turn from man to the animals which we are most familiar with, the common domestic quadrupeds, we see that they undergo a series of changes not very dissimilar to those which man himself must pass through. An old horse, an old dog, an old cat, shows pretty much the same sort of decrepitudes which characterize old men. But when we pass farther down in the scale to the fishes, or even to a frog, we discover great differences. Do you think you could tell a frog when it is old by the way it walks—for it never walks—or a fish by the amount of hardening of the lungs, when it has none? Yet the lack of lungs is characteristic of the fish. And what becomes of the theory of arterial sclerosis when we go still lower in the animal kingdom, towards its lowermost members, and find creatures which live and thrive and have lived and thriven for countless generations, yet have no arteries at all? They, of course, do not grow old by any change of their arteries. But when we come to study these various animals more carefully, we learn that in them the anatomical and physiological features which I have indicated to you in my description of the changes in the human being, are paralleled, as it were, by similar changes; but only by similar, not by identical, changes. If we examine the insects, for instance, we see that in an old insect there is a hardening of the outer crust of the body which serves as a shell and a skeleton at once. That hardening increases with the age of the individual. We can see in the insect a lessening development of the digestive tract, and we can see—it has been demonstrated with particular nicety—a degradation of the brain. Insects have a very small brain, but when a bumblebee, or a honeybee, grows old, as he does in a few weeks after he acquires his wings, we see that the brain actually becomes smaller, and not only that, but as I shall be able to demonstrate to you with the lantern in the next lecture, the elements which build up the brain have each of them become smaller and the diminution in the size of the brain is due in part to the shrinkage of the single microscopic constituents. There is another point of resemblance. We find that when one of the better parts of the body undergoes an atrophy, it becomes not only smaller, but its place is to a certain extent taken by the inferior tissues—especially by those which we call comprehensively the connective tissues, which might perhaps be best described to a general audience as that which is the stuffing of the body and fills out all the gaps between the organs proper. In consequence of performing this general function, they are very properly called connective tissues, since they connect all the different organs and systems of organs in the body together. Now in every body there is a continual fighting of the parts. They battle together, they struggle, each one to get ahead, but the nobler organ, generally speaking, holds its own. There are early produced from the brain the fine bundles of fibers which we call the nerves, which run to the nose, to the tongue and to the various parts of the body. When these appear all the parts of the body are very soft. Afterwards comes in the hard, and, we should think, sturdy bone, but never, under normal conditions, does the bone grow where the nerve is. The nerve, soft and pulpy as it seems, resists absolutely the encroachment of the bone, and though the bone may grow elsewhere, and will grow elsewhere the moment it gets a free opportunity, it can not beat the soft delicate nerve.[6] Similarly we find that the substance which forms the liver is pulpy, very delicate. Those of you who have seen fresh liver in the butcher's shop know what a flabby organ it is, and yet though it is surrounded by the elements of connective tissue, which with great zest and eagerness produce tough fibers, it never gives way to them. The connective tissue is held back by the soft liver and kept in place by it. The liver is, so to speak, a nobler organ than the connective tissue and holds sway ordinarily; but in old age, when the nobler organs lose something of their power, then the connective tissue gets its chance, grows forward and fills up the desired place, and acquires more and more a dominating position. We can see this alike in the brain of man and in the brain of the bee. That which is the nervous material proper, microscopic examination shows us to be diminished everywhere in the old bee and in the old man, and the tissue which supports it, which is of a coarser nature and can not perform any of the nobler functions, fills up all the space thus left, so that the actual composition of the brain is by this means changed. There is, you see, therefore, during the atrophy of the brain, not only a diminution of the organ as a whole, but there is the further degradation which consists in the yielding of the nobler to the baser part, if I may so express myself. That, you recognize, necessarily implies a loss of function. The brain can not under senile conditions do the sort of fine and efficient work which it could do before. Now if we go on from insects to yet lower organisms, we see less and less appearing of an advance in organization, of correlated loss of parts, and when we get far enough down in the scale, senescence becomes very vague. The change from youth to old age in a coral or in a sponge is at best an indefinite matter.

I should like, did the length of the course permit, to enlarge greatly upon this aspect of the question, and explain to you how it is that as the organism rises higher and higher in the scale, old age becomes more and more marked, and in no animal is old age perhaps so marked, certainly in no animal is it more marked, than in ourselves. The human species stands at the top of the scale and it also suffers most from old age. We shall learn, I hope, more clearly later on in the course of these lectures, that this fact has a deeper significance, that the connection between old age and advance in organization, advance in anatomical structure, is indeed very close, and that they are related to one another somewhat in fashion of cause and effect; just how far each is a cause and how far each is an effect it would perhaps be premature to state very positively; but I shall show you, I think in a convincing way, that the development of the anatomical quality, or in other words of what we call organic structure, is the fundamental thing in the investigation of the processes of life in relation to age. We can see it illustrated again very clearly indeed when we turn to the study of plant life, for plants also grow old. Take a leaf in the spring. It is soft as the bud opens. The young leaf is delicate. It has a considerable power of growth. It expands freely, and soon becomes a leaf of full size. Then comes the further change by which the leaf gets a firmer texture; the production of anatomical quality in the leaf, so to speak, goes on through the summer, and the result of that advance in the anatomical quality is that the delicate, youthful softness and activity of the leaf is stopped. It can not grow any more; it can not function as a leaf properly any more. The development of its structure has gone too far and the leaf falls and is lost, and must be replaced by a new leaf the next year. When we examine the changes that go on in any flowering plant, we observe always that there is this production of structure, and then the decay, the end or death. At first structure comes as a helpful thing, increasing the usefulness of the part, and then it goes on too far and impairs the usefulness, and at last a stage is produced in which no use is possible any longer—the thing is worthless. It is cast away in the case of the plant life; and this casting away of the useless is a thing not by any means confined to plants; it occurs equally in ourselves all the time; at every period of our life we have been getting through with some portion of our body; that portion acquired a certain organization, it worked for us awhile, and then being done with it, we threw it away because it was dead. Very early in the history of every individual there was a production of blood, and then followed the destruction of some of the blood corpuscles and their remains were used for various purposes. The pigment which is in the liver comes from the destroyed blood corpuscles, and it is believed that the pigment which colors the hair is derived from the same source. The blood corpuscles contain a material which when chemically elaborated reappears as the deposit which imparts to the hairs their coloration. You, of course, are all familiar with the loss of hair. It occurs to everybody, but did you ever think that it means that the hair which has lived has died, and that that hair which was a part of you has been cast off? That is what the loss of hair means to the biologist—the death of a part and the throwing away of it, and it is typical of what is going on through the body all the time. It occurs in the intestines, where the elements which serve for purposes of digestion are continually dying and being cast off. The outer skin is constantly falling off and being renewed, and that which goes is dead. In every part of the body we can find something which is dying. Death is an accompaniment of development; parts of us are passing off from the limbo of the living all the time, and the maintenance of the life of each individual of us depends partially upon the continual death going on in minute fragments of our body here and there.

Our next step in this course of lectures will carry us into the microscopic world, and with the aid of the lantern at the next lecture I shall hope to demonstrate to you a little of the microscopic structure of the body and of the general nature of the change, which exhibits itself in the body from its earliest to its latest condition. With such knowlege in our minds, we shall be able next to study some of the laws of growth. We shall gain from our microscopic information a deeper insight into some of the secrets of the changes, which age produces in the human body.

- ↑ Lectures delivered at the Lowell Institute, Boston, March, 1907.

- ↑ This statement is the one currently accepted—but I have found, as yet, no exact investigation upon the relative size and number of the muscle fibers in old persons.

- ↑ My friend, Professor W. T. Porter, has had the kindness to compile the following table for me, showing the pulse frequency from one to eighty years. For the first two months after birth, the rate is about 130, after the third month 140. The fœtal rate is 135 to 140.

- ↑

Ernst Handmann has recently published statistics on the growth of brain, based on measurements at the Leipzig Pathological Institute. See Archiv f. Anat. u. Entwickelungsges., 1906. p. 1. The following summarizes his results:

Brain Weight in Grams Age Male Female 4-6 1215 1194 7-14 1376 1229 15-49 1372 1249 50-84 (89) 1332 1196 - ↑ L'Année biologique, Tome III., p. 256, 1897.

- ↑ The nerve fibers of the olfactory membrane arise very early in the embryo and form numerous separate bundles. Later the bone arises between the bundles, for each of which a hole is left in the osseous tissue, so that the bone in the adult has a sieve-like structure, and hence is termed the cribriform plate. It offers a striking illustration of the inability of hard bone to disturb soft nerve fibers.