Popular Science Monthly/Volume 85/December 1914/The Cinchona Botanical Station I

THE

POPULAR SCIENCE

MONTHLY

DECEMBER, 1914

| THE CINCHONA BOTANICAL STATION |

By Professor DUNCAN S. JOHNSON

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY

THE botanical laboratory and garden at Cinchona, in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica, which for the past ten years has been a tropical station of the New York Botanical Garden, is now to be maintained under the auspices of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, with the cooperation of the Jamaican government. The British Association is concerned primarily in making Cinchona available for British investigators, but it is believed that, except when the laboratory is taxed to its capacity by appointees of this association, its privileges, will be extended, upon the recommendation of the Jamaican government, to properly accredited American botanists.

The opening of a new chapter in the history of this long-established seat of botanical activity makes this a fitting time to call attention to the work that has been done at this laboratory during the past forty years, and to its peculiar advantages in location as a botanical station. We may also note the evidence for the need of such a laboratory, and the character of its possible service to botanical science. With the general appreciation of the variety of plant material and other advantages to be had at this laboratory, it is believed that Cinchona will be more and more resorted to by investigators working on those botanical problems which can best be studied with organisms living under tropical or subtropical conditions.

The need of a botanical laboratory in the western tropics, which could offer the facilities and give the stimulus afforded to old-world botanists by the Dutch garden at Buitenzorg, in Java, has long been recognized by American botanists. It is true that biological explorers in quest of new forms, or of new evidence concerning the distribution of known forms, have been searching since the days of Hans Sloane (1687) and Humboldt (1799-1804) through many parts of the western tropics. The plant taxonomists of Europe, of the H. S. National Herbarium, of the Columbian Field Museum, and especially of the New York Botanical Garden, have recently made extensive collections in the continental and Antillean portions of the American tropics. But facilities have been lacking for working out the life-histories or the physiology and ecology of tropical and subtropical seaweeds, as this has been done at Naples and Ceylon; the chance has been wanting to select, study and carefully preserve developmental stages of tropical mosses, ferns and seed plants, and to make investigations of the physiology of growth, nutrition and other activities of plants near the equator, as these have been made at Buitenzorg. This sort of opportunity for studying tropical plants where they must be studied—in their tropical surroundings—has seldom been offered to American investigators until within the last decade. The more or less temporary summer laboratories established in the western tropics have been located directly upon the seacoast, primarily with a view to their fitness for zoological work. They have usually proved unattractive to botanists engaged in studies other than those upon marine algae. This has been largely true of the summer laboratories established by the Johns Hopkins University in the Bahamas and Jamaica, by Harvard University in Bermuda and by the Carnegie Institution on the Dry Tortugas. It is evident, therefore, that for many kinds of botanical research a laboratory must be established at a site selected with these in view—in other words, it must be primarily a botanical station.

A serious attempt to arrange for the establishment of an American tropical laboratory was made by certain of the botanists of this country in 1897. The desirability of such a laboratory was pointed out by The Botanical Gazette, and a commission composed of D. T. MacDougal, D. H. Campbell, J. M. Coulter and W. G. Farlow was chosen to select a site. This Tropical Laboratory Commission, after profiting by such information and suggestions as they could obtain, and after two of its members, Drs. MacDougal and Campbell, had visited Jamaica in 1897, was inclined to favor that island as the location for the laboratory. During the presence of these two commissioners in Jamaica they were aided by Hon. William Fawcett, late director of Public Gardens and Plantations, William Harris, superintendent of Public Gardens and Plantations and Professor James E. Humphrey, of the Johns Hopkins University, who was at this time in charge of the Johns Hopkins Laboratory, established at Port Antonio. The sad fate of Professor Humphrey and of that promising young zoologist Franklin Story Conant, as victims of the unwonted visitation of yellow fever to Jamaica, undoubtedly checked the enthusiasm of many who had been interested in establishing a tropical laboratory. The anticipated encouragement and cooperation were not given to the commission, and, in consequence, the search for a site and all further work on the project were, for the time, abandoned. The project was not again taken up by American botanists or institutions during the following six years.

In August, 1903, the Jamacian government, having abandoned Cinchona cultivation, decided to lease the Cinchona property. Through the suggestion of the late Lucien M. Underwood and the writer, and by the prompt action of Director N. L. Britton and Dr. D. T. MacDougal, Cinchona was leased by the New York Botanical Garden. It was maintained by the garden as a laboratory, and as a substation for the propagation of tropical plants. The director of the garden also placed the laboratory and other equipment at the disposal of botanical investigators, of whom more than thirty have worked at Cinchona during the past ten years.

In the last decade, it is true, several other botanical laboratories, all of them primarily for experiment-station work, have been organized in the American tropics. Two of these were maintained by commercial organizations in Mexico. Of the other three, two, at Miami, Florida, and Mayaguez, Porto, Rico, are supported by the United States, and a third, at Paramaribo, is maintained by the government of Dutch Guiana. At none of these has much botanical research thus far been carried on, except the economic agricultural work of the regular staff members.

It is thus evident that the interest of American botanists desiring a tropical laboratory has centered about Cinchona for the past two decades. There is good reason to believe that this interest will continue and increase. When, therefore, it was learned that Cinchona, the only station in the western tropics for the study of pure botany, was not to be again leased by the New York Botanical Garden, the Botanical Society of America, meeting in Cleveland, attempted to secure the continuation of the use of the Cinchona station for American botanists. For this purpose a committee was appointed consisting of D. S. Johnson (chairman), N. L. Britton and D. H. Campbell, and an appropriation was made to pay a year's rental, if this should be necessary, while more permanent arrangements were being perfected. Before the committee had had opportunity to act, it learned of the prospect that the Jamaican government would make the privileges of Cinchona available for American investigators. The publication of this account of Cinchona, and its advantages as a botanical station, may serve to indicate the interest of the committee in its work, and its appreciation of the encouragement given to botanical investigators of our country by the Jamaican government.

Location

The Hill Garden, or "Government Cinchona," as it is commonly called by Jamaican planters, is a reservation of many thousand acres, where the cinchona tree, from which Peruvian bark and quinine are obtained, was introduced 45 years ago. Here, and on the neighboring private plantations, it was grown for profit, until the cheaper labor and transportation in the parts of India and Java devoted to this crop greatly lowered the price of the bark.

Lying on a rugged spur stretching southward two miles from the main ridge of the Blue Mountains, the Cinchona reservation extends upward from the cleared slopes at the 4,500-ft. level to the well-wooded peaks 6,100 feet high, in the main range itself. Practically all the Blue Mountan country above the 4,500-foot level is reserved by the government as a water shed, and thus forms an immense area of mountain forest that may be used for floristic exploration and ecological study. At a spot commanding a remarkable prospect, on the shoulder near the south end of the spur, stands the Cinchona residence and laboratories, situated at an altitude of 4,900 feet. The house is the highest dwelling of any pretensions anywhere in the West Indies.

History

The idea of developing a hill garden, or "European garden," as he called it, was conceived by a governor of the colony, Sir Basil Keith, in 1774. He planned especially to introduce the cultivation of European vegetables in the cool, moist hill country. The plan was first realized in 1869, through the energy of a later governor, Sir John Peter Grant, whose primary object was the encouragement of the culture of Peruvian bark, coffee and tea. Here, in the early seventies, scores of acres were cleared and planted with seedlings of several species of Cinchona. These were derived from plants brought out of Peru in 1860 by Clements Markham. In 1874 the Jamaican government organized at Cinchona an experiment station, which became the center of botanical work in the island. A director's residence, other dwellings, offices, laboratories, greenhouses, servants' quarters and stables were erected. A beautifully planned garden was developed about these buildings, and planted with hundreds of subtropical and temperate-zone plants.

Here was stationed during the prosperous days of cinchona culture, nearly the whole botanical staff of the Department of Public Gardens and Plantations. For seven years, under Sir Daniel Morris (18791886), and eleven years under the Hon. William Fawcett (1886-1897), the staff was engaged in agricultural and in some purely botanical researches. Methods of propagating, cultivating, harvesting and curing cinchona, tea, etc., were studied. At a lower altitude experimental plantations were made of oranges, orris root, forage plants, and fiber plants such as China grass, which showed that these can be grown successfully in the Hills. The staff included a trained English gardener, William Nock, brought over to demonstrate the possibility of cultivating "English" vegetables in these higher parts of the island. This experiment was entirely successful, and in consequence the natives now grow these vegetables, then carry them as head loads for 15 or 20 miles over the mountain trails to the Kingston market. Besides these purely agricultural investigations, important taxonomic studies were made of the flowering plants of this most interesting part of Jamaica by Messrs. William Fawcett and William Harris, of the staff. Diligent search for new forms in the more inaccessible regions was made especially by Mr. Harris, while G. L. Jenman, then superintendent of Castleton Gardens, studied the ferns of this area. Hundreds of species of mosses, ferns and seed plants new to the island, and to science, were found by these workers. The Flora of Jamaica, now being published by Fawcett and Rendle from the British Museum, was initiated at Cinchona. Records were also made for twenty years of the temperature and rainfall at several stations in this region, including Blue Mountain Peak, at 7,423 feet elevation.

Some sixteen years ago the staff was removed to new headquarters at Hope Gardens, near Kingston, from which the lowland agriculture, now of most importance to the island, can be more readily studied and aided. For a number of years after the removal of headquarters, the Cinchona Station was not occupied, except occasionally as a summer retreat from the heat of the plains, by the governor, or other island officials, or by visiting botanists. For example, it was used as a base for botanical work by Campbell in 1897, by Harshberger in 1902, and by Underwood, Maxon, Johnson and Shreve in 1903.

The importance of the later history of Cinchona, during its lease by the New York Botanical Garden, has already been suggested. Aside from being used as a propagating station, it has been the base for much purely botanical work by Americans and Englishmen. Researches have come from Cinchona during the past decade by workers from the New York Botanical Garden, the United States National Museum, Columbia, Yale and Johns Hopkins Universities, and Wellesley College. Important studies of the ecological distribution of Blue Mountain plants have been made here by Forrest Shreve, of Johns Hopkins University and of the Carnegie Institution. Developmental and anatomical investigations have been initiated at Cinchona on the Orchidaceae, Piperaceae, Loranthaceae, Filicales and Hepaticeae by investigators from Columbia, Glasgow, Johns Hopkins and Yale Universities. Aside from the investigations accomplished, many botanists have here had their first opportunity of perceiving the intimate dependence of certain types of extreme specialization in plant structure on the accentuation of definite climatic or edaphic conditions. In other words, many have here first seen ferns and seed plants living as epiphytes, and have first appreciated the extreme diversity of habit and complexity of composition attained by the plant life of a primeval forest under tropical conditions.

Cinchona and the Surroundings

living and sleeping accommodations for eight or ten workers. There are two laboratories, each well lighted on two or three sides, that will accommodate the same number of workers, with tables, shelving, some simple glassware and a supply of plant dryers. There are two greenhouses that can be used for keeping experimental material under constant conditions, and which incidentally collect water for two large cisterns that supply the laboratories and house. The clear, absolutely pure water for drinking and cooking is brought on the head of a native carrier from the springs of the Clyde River, 500 feet below Cinchona.

The finely terraced garden about the house and laboratories is maintained in excellent condition. Despite the ravages of the hurricane of 1903, it still contains numerous fine specimens of tropical, subtropical and temperate-zone shrubs and trees. There are the native tree ferns, junipers, Podocarpus, orchids, bromeliads and a great Datura with

corollas a foot long, that have been transplanted from the mountains behind Cinchona. There are fine examples of many Himalayan and Cape of Good Hope species. Large trees are here of Cryptomeria, Cupressus Lawsoniana, Pinus Massoniana, and two species of Podocarpus. The genera Grevillea, Hakea, Callistemon, Gordonia, Pittosporum and the beautiful Acacia are represented by from one to several species each. There are splendid specimens or clumps of each of a dozen species of Eucalyptus. Eight or ten species of subtropical palms are found here, together with Agaves, Yuccas, New Zealand flax with leaves

six feet long, and the huge Amaryllidaceous Doryanthes. There are clumps of beautiful Azaleas, whole hedges of bamboo, and thickets of two Asiatic raspberries ten feet high. On the terraces near the house are dozens of roses, Fuchsias with two-inch trunks, and tangled masses of deliriously scented heliotrope and Mandevilla, besides dozens of the more usual garden plants of temperate zones. The laboratories are nearly hidden by great clumps of pampas grass.

Among the flowers of the garden flit many beautiful humming birds, while up from the valleys below float the mellow, plaintive notes of a thrush—the solitaire. The garden at Cinchona, like all the surrounding region, is free from snakes and from troublesome insects. The native negro people of the Hills are courteous and obliging, and, of course, speak English.

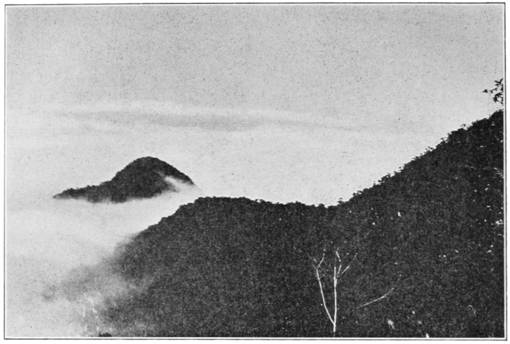

The surroundings of Cinchona, beyond the confines of the garden, are equally interesting. Just north of the house a high knob of the spur rises a hundred feet above it. Then, after dropping 200 feet, to a saddle ten yards wide, at St. Helen's Gap, the ridge continues northward, growing wider and higher, to the Blue Mountain range itself. Southward from the house the ridge drops off abruptly, except on the southeast, so that from the terrace one may look off over the Port Royal Mountains to Kingston Harbor and Port Royal, fifteen miles away and nearly a mile below. East and west of Cinchona are the steep-sided valleys, half a mile deep, of the Green and Yallahs Rivers, the lower slopes of which have been largely cleared and planted with coffee or vegetables. These valleys, with their changing lights and shadows, from dawn till twilight, are a constant delight to the dweller at Cinchona. In the early-morning they are in deep shadow long after the sun has lighted up the mountain tops around them. A thin veil of cloud floats far down below, and, in the stillness of the morning, the faint roar of the river, coming up from the dimly seen bottom, makes the valley seem miles in depth. All day long the clouds, driven by the northeast trade winds, roll over the Blue Mountains from the cool north side and quickly melt away in the dry air above the warm southern valleys. In the afternoon the sun sets in these valleys at four or five o'clock, and their slopes cool down rapidly. Then bits of the flowing cloud break off and slowly settle down into the valley beneath, to form anew the billowy curtain that screens the valley each night. A sight long to be remembered is such a sea of cloud, reflecting from its top the glow of a sunset, or the brilliant light of the tropical moon.

During the rainy season, or "the seasons," as Jamaicans call it, the clouds become denser south of the mountains. Then Cinchona itself is enveloped in cloud most of the time for days together. I might almost say enveloped in water, for the rain is so heavy that a tumber will fill directly from the skies in three or four hours. An inch an hour may fall for hours together. The spring rainy season, of heavy rains both

day and night, extends over two or three weeks in May or early June. A second one occurs in October. For several weeks preceding each of these rainy seasons there may be dense clouds and occasional showers at midday. From four or five o'clock in the late afternoon, till nine or ten in the morning, the sky above is cloudless. The sun sets in splendor over the western peaks and the moon and stars shine out with a sparkling brilliancy. The clear days after "the seasons" are the most beautiful of all the year. On the mountains 'round about, where all had been dark green and gray before the rains, the foliage now takes on a new brightness, and the scar-like watercourses are now veiled by white cataracts that plunge hundreds of feet down the mountainsides. Beyond the lower mountains of Guava Ridge one can see on, past the foaming surf line, out a hundred miles over the blue Caribbean.

During the late summer, and again in midwinter, the rainfall may average but three or four inches per month, and it may even be fair for weeks together, so that the soil of the hilltops and ridges about Cinchona becomes very dry. The total rainfall for the year at Cinchona is from 100 to 115 inches. North of the mountains, three miles away, there may be 200 inches in a year. The temperature at Cinchona ranges from 48 to 78 degrees, but these extremes are seldom reached. In June, 1906, while New York and Baltimore had temperatures in the upper nineties, the thermometer at Cinchona reached 72 degrees but twice, and then for but an hour or two at a time. At night, on these same days, with temperatures of 52 or 54 degrees, we were ready to enjoy the open fire of juniper logs in the living room of the bungalow.