Punch/Volume 147/Issue 3827

"In Buenos Aires and other parts of Argentina," The Express tells us, "people are tired of the war, and a brisk trade is being done in the sale of buttons to be worn by the purchaser, inscribed with the words 'No me habla de la guerra' ('Don't talk to me about the war')." The Kaiser, we understand, has now sent for one of these buttons.

⁂

The Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, in an order to his troops last week, referred to the British in the following words:—"Here is the enemy which chiefly blocks the way in the direction of restoration of peace." Conceive a "contemptible little army" being able to do that! It makes one wonder whether the first epithet was perhaps a misprint for "contemptuous."

⁂

The Germans are now calling the Allies a Menagerie, though curiously enough it is the others who have a Turkey waddling after them.

⁂

According to a report which reaches us the crews of the Goeben and Breslau are wearing a most curious garb, being clothed in Turkish fezes and breaches of neutrality.

⁂

"GERMANS MOWED DOWN

French Marines' Big Feet."

This is really a most unfortunate misprint, for it is just this kind of carping statement that leads the Germans to say we are falling out with our Allies.

⁂

There is much speculation as to whether there is German blackmail behind the announcement that the maximum period of quarantine for imported dogs has been reduced from six months to four.

⁂

The only animals left alive in the Antwerp Zoo are reported to be the elephants, which are now being used for military traction purposed. Later on it is proposed by the Germans to drive them into the lines of the Indian troops with a view to making the latter home-sick.

⁂

Mr. Algernon Ashton asks in The Evening News, "Why is the Poet Laureate so strangely silent?" Everyone else will remember Mr. Bridges' patriotic lines at the beginning of the War, and we begin to suspect that Mr. Ashton's well-known repugnance to writing for the papers has been extended to the reading of them.

⁂

The Daily Mirror, to signalise its eleventh birthday, produced a "Monster Number," yet it contained no portrait of the Kaiser.

⁂

Happening to meet a music-hall acquaintance we asked him how he thought the war was going, and he replied, "Oh, I think the managers will have to give in."

⁂

America is evidently attempting to attract some of the devotees of winter sports who usually go to Switzerland. Another landslide on the Panama Canal is now announced.

⁂

We are sorry to have to bring a charge of lack of gallantry against The Leicester Mail. We refer to the following passage in its description of an ovation given to Driver Osborne, V.C., at Derby on the 31st ult. After describing how, in the course of a great reception given to him by a large crowd at the station, two or three buxom matrons insisted upon embracing him, our contemporary continues: "Driver Osborne has now practically recovered, and reports himself for duty again at the end of the week."

⁂

The municipality of Berlin has decided to substitute for the existing designations of some of the principal streets in that city the names of "German generals who have become famous during the present war." This, however, will not involve many alterations.

⁂

Orders have been issued by the Federal Council of the German Empire that no bread other than that containing from 5 to 20 per cent. of potato flour will be allowed to be baked. Such bread is to be sold under the name of "K" bread. At first this was taken to be a graceful tribute to Lord Kitchener, but it is now officially stated that "K" stands for the German for potatoes.

⁂

The Kölnische Zeitung complains that English prisoners in Germany "are allowed to live the lives of Olympian Gods." Our choleric contemporary is evidently unaware that we are allowing German prisoners to reside in Olympia, which is the next best thing to Olympus.

⁂

The British steamer Remuera reported on reaching Plymouth last week that a German cruiser had attempted to trap her by means of a false S.O.S. signal. We ought not, we suppose, to be surprised at a low trick like this from the s.o.s.sidges.

⁂

There is one quality that no one can with justice deny to the Germans, and that is thoroughness. The other day, having laid a mine, they seem to have used one of their own cruisers to test its destructive power.

⁂

"It is noticeable," says The Daily Mail, that the Kaiser's speeches no longer include references to God, only Frederick the Great." This confirms the rumours of a quarrel.

The Airship Menace.

Famous Town Captured by Germans.

"In the south of Ypres we have lost some points, D'Appui, Hollebeke, and Landvoorde."

Worcester Daily Times.

If your map doesn't give D'Appui, buy a more expensive one.

"Capstan Hands.—First-class Men, used to chucking work, for motor vehicle parts."

Advt. in "The Manchester Guardian."

They ought to be easy enough to get.

"Guardsmen again provided a dramatic element in the trial by guarding the prisoner and the door which fixed bayonets."

Evening News.

You should see our arm-chair give the salute.

To share their glory who have gladly died

Shielding the honour of our island shores

And that fair heritage of starry pride,—

Now, ere another evening's shadow falls,

Come, for the trumpet calls.

This message for an everlasting stain?—

"England expected each of all her sons

To do his duty—but she looked in vain;

Now she demands, by order sharp and swift,

What should have been a gift."

To stand by England in her deadly need;

If still her wounds are but an idle tale

The word must issue which shall make you heed;

And they who left her passionate pleas unheard

Will have to hear that word.

Your right to rank, on Memory's shining scrolls,

With those, your comrades, who made haste to choose

The willing service asked of loyal souls;

From all who gave such tribute of the heart

Your name will stand apart.

Shall be their certain portion who pursue

Pleasure "as usual" while their country's claim

Is answered only by the gallant few.

Come, then, betimes, and on her altar lay

Your sacrifice to-day!

O. S.

Bordeaux.

Sire,—You will pardon me, I know, if for a moment I break in upon the serious occupations and meditations in which your time must be spent. I like to picture you to myself in the midst of your Staff, working out for them and your armies great problems of strategy and devising those movements which, so far, have overwhelmed not your foes so much as the minds of your fellow-countrymen. You too, Sire, sanguine and impetuous as is your nature, are no doubt beginning to realise that a great nation—let us say France, for example—is not to be overcome by mere shouting and the waving of sabres, or by the making of impassioned speeches in which God, having been acclaimed as an ally, is encouraged to perform miracles for the benefit of the Prussian arms. I do not deny that your soldiers are brave and that your armies are well equipped; but Frenchmen too have guns and bayonets and swords and shells and know how to make use of them, and their portion of courage is no smaller than that of the Prussians, or even of the Bavarians whom you have lately been vaunting. Moreover—and this you had perhaps overlooked—they have something which is deadlier and more enduring than shot and shell and steel—the unconquerable spirit which leaps up in the hearts of men who are gathered to defend their country from invasion and their national existence from destruction.

Oh, Sire, how little you have understood France and her people; how little you have understood the minds and motives of men! "France," your Professors and your Generals told you, "is degenerate; her population is smaller than ours; she has lost her skill in fighting and her courage; she has no culture, never having heard of Treitschke and having neglected the inspired writings of Nietzsche; she will be an easy prey, for no one will lift a hand to help her. England is lapped in ease behind her ocean and will never fight again; Russia is distant and slow, and we can despise her; Belgium will never dare to deny us anything we care to ask. Let us make haste, then, and crush France to the earth for ever." So you planned, and your legions set out to trample us down, with the result that is now before the eyes of the world.

Only a few words more. There is at Sampigny, in Lorraine, a modest country-house, which was, in fact, my home. Your troops passed through the place, and for no military reason that I can discover they reduced this house to ruins. I know that that is a small price to for the honour of being allowed to represent the French nation in this hour of peril and glory, and I pay it willingly. When so many are laying down their lives with joy why should I complain because a few walls have been shattered? But I am reminded and I wish to remind you of another story. One hundred and eight years ago, in October, the Great Napoleon, having scattered your predecessor's armies to the four winds of heaven, proceeded to Potsdam, where he visited the tomb of the great Frederick. They showed him the dead King's sword, his belt and his cordon of the Black Eagle. These Napoleon took, with the intention of sending them to Paris, to be presented to the Invalides, amongst whom there still lingered a few who had been defeated by Frederick at Rosbach. Certainly the relics took no shame from such a seizure and such a guardianship. But the palace at Potsdam was not destroyed and stands to this day. I do not wish to liken myself to Frederick, nor do I compare you with Napoleon, but I tell you the story, which is true, for what it is worth. I wonder if you will appreciate it?

Agree, Sire, the expression of my distinguished consideration.

Raymond Poincaré.

THE IRON CROSS.

(For German looters.)

S' appiccavan' i ladri in sulle croci;

In tempi men barbari e più leggiadri

S' appiccano le croci in petto ai ladri.—Giusti.]

The thief was hung up on the cross for his crimes,

But Culture to savages offers relief—

The cross is now hung on the breast of the thief.

"Amended and more stringent regulations concerning the lights of London have been issued by Sir E. R. Henry, the Commissioner of Police. A number of them are in the same as which were published in The Globe nearly a month ago, but others make important changes. For example, the third order, as originally drafted, ran: 'The intensity of the inside lighting of shop fronts must be reduced from 6 p.m. or earlier if the Commissioner of Police on any occasion so directs', but it is now as follows:—

The intensity of the inside lighting of shop fronts must be reduced from 6 p.m. or earlier if the Commissioner of Police on any occasion so directs."—Globe.

The italics ought to make it a lot darker.

Gifts of money for the purchase of blankets are being made in Germany not less than here, and we understand that a large sum has been sent out to South Africa addressed: "De Wet Blanket Fund."

The Kaiser (to Turkey, reassuringly). "LEAVE EVERYTHING TO ME. ALL YOU'VE GOT TO DO IS TO EXPLODE."

Turkey. "YES, I QUITE SEE THAT. BUT WHERE SHALL I BE WHEN IT'S ALL OVER?"

Talkative Passenger. "I see that the young Earl of Harboro' has just done a very plucky act at the front."

Rabid Socialist (indignantly). "Well, so he ought."

(A mild apostrophe to the young man next door.)

Melodious distych from the music-balls,

Piping in summer from beneath a pergola,

Piping to-day behind these party-walls,

Three months ago and more, when Mars had thrust us

In doubt and dread alarm and cannons' mist,

I found one solace, for I mused, "Augustus

Will probably enlist.

I know not if his heart is full of grit,

But I do know that he disturbs the baby,

And, judging by his lungs, he must be fit;

His is the frame, or else I've never seen one,

His are the fitting years to fight and roam,

He has no ties (except that pink and green one)

To tether him to home.

If not (for glory of his long campaign)

We shall be thrilled to hear the sergeant-major

Singing the good old songs he loved again;

Bellona, too, has something of the witch in her;

It may be he will learn more tact and grace

When that mild tenor has been turned by Kitchener

Into a throaty bass."

You have not budged one inch upon the road;

While half the lads have got their khaki trousseau,

You still retain that voice and nut-like mode;

Peace holds you with the tightness of a grapnel,

And, still adhering to her ample hem,

You enfilade us with your tuney shrapnel

From 9 to 12 p.m.

The kindly bonds that neighbours ought to keep,

I'll take a summons out to curb the nuisance

Unless you stop it. Can I laugh or weep

For those who fling their challenge at the blighting gale,

Who smile to hear the cannon's murderous croon,

When you go on like a confounded nightingale

Under a fat-faced moon?

Through all the lamp-lit hours with festal fuss,

And songs are changed, and so's the time for singing,

But I'd be greatly pleased to hear you, Gus,

Out in the road there, watched by Anns and Maries,

Op'ning your throttle to the mid-day light;

Fate gave it you to prove that Tipperary's

A long way off. Left-Right!

Evoe.

We commend The Pioneer to the notice of our evening contemporaries. Its "Extraordinary War Special"—price, one anna—consists of the following:—

"No Reuter received since 8.30 a.m."

A more enterprising paper, such as The ——— or The ——— [censored] would have provided some new headlines from yesterday's news.

Tommy Brown has already been in disgrace, although it is only a fortnight since he wrote the famous patriotic essay which determined Mr. Smith, his Form-master, to go to the Front. You see, Miss Price, who is deputising for Mr. Smith, does not like lizards, and has an especial aversion to white rats, whereas Tommy is very fond of these and other dumb animals.

So Tommy was reported to the Headmaster. At first the Headmaster thought that the application of "somewhat severe measures, my boy," would meet the case; but whoever heard of caning a curly-headed boy with blue eyes and an ink-stain on both lips? The interview took place in the Headmaster's study. To the question, "What do you mean, Sir, by bringing lizards and white rats to school?" Tommy said, "Yes, Sir," and then, after thinking for fully three seconds, he said he had a ferret at home, and did the Headmaster know how to hold a ferret so that it couldn't bite you?

It seems that ferrets, if they once get hold of your thumb, never let go—not never—and that you have to force their jaws open with a penholder; also ferrets exhibit a marked preference for thumbs. All this information Tommy conveyed without drawing a breath. The Headmaster said, "Quite so, my boy, quite so. But don't you know it is extremely reprehensible conduct to bring animals to school in your pocket?" Well, you see, that is how Tommy's mother talks to him, so he knew what to do, and, looking up into the Head-master's face with that wistful look of his, he imparted the deep secret that he had a tortoise.

Tortoises, the Headmaster learnt, had a way of getting lost among the cabbages, but, if you wanted to prevent them from straying, all you had to do was to turn them over on their backs and put a piece of brown paper over them for their feet to play with. Also they were stuck fast in their shells, because Tommy had tried. A boy had told Tommy that tortoised laid eggs, but although Tommy had showed his tortoise a hen's egg and then put the tortoise in a nice new nest the tortoise had taken no step in the matter.

However, Tommy promised never to bring any more animals to school and to express his sorrow to Miss Price. And he was richer by sixpence when the interview closed.

At parting, Tommy offered to lend the Headmaster his tortoise for a week, and told him that, if he stood for a whole hour on its back, it wouldn't hurt it, because Tommy had trained it; also it never crawled out of your pocket.

Tommy apologised to Miss Price for bringing the white rats to school—they weren't white rats really, not to look at; they were rather piebald through constant association with ink. Also he brought an apple and showed her how, by holding it a certain way whilst eating it, she would miss the bad part. In further sign of amity he showed her his knife, and especially that instrument in it which was used for removing stones from horses' hoofs. Not that Tommy had removed many stones from horses' hoofs, not very many, but if you had a tooth that was loose it was very helpful. Miss Price gave him a new threepenny bit, and Tommy tried hard to please her in arithmetic by reducing inches to pounds, shillings and pence.

With ninepence in his pocket Tommy felt uneasy. It was a question between a lop eared rabbit and a mouth-organ. A lop-eared rabbit, that is to say a proper one, cost two shillings; for nine-pence it was probably that you could only get a rabbit which would lop with one ear.

Besides, a lop-eared rabbit meant a hutch, and he had already used the cover of his mother's sewing-machine for the piebald rats.

One the other hand, you could get a mouth-organ with a bell on it for nine-pence; he knew.

It was a splendid instrument!

Tommy took it to bed with him and put it under his pillow, and when his mother came to see that he was all right at night his hand was clutched round it as he slept—content.

The next day Tommy gave an organ recital in the playground before a large and enthusiastic audience. For a marble he would let you blow it while he held it. For two marbles you could hold it yourself.

One boy paid the two marbles, and noticed the words "Made in Germany" in small letters on the under side. The silence that followed the announcement of this discovery was broken only by the sound of Jones minor biting an apple. All eyes were on Tommy Brown. For the fraction of a second he hesitated, and in that fraction Brook tertius giggled.

Tommy seized the mouth-organ with a determination that was almost ferocious; he threw it on the ground, stamped on it with his heel again and again, and finally took and pitched it into a neighbouring garden. He then fell upon Brook tertius and punched him until he howled.

Before Tommy Brown could go to sleep that night his mother had to sit by his bed-side and hold his hand; he never released her hand until he was fast asleep. How like his father (the V.C.) he looked! She wondered what made him toss so in his sleep and what had become of his mouth-organ with the bell on it.

HOW TO BRING UP A HUN.

The Teutonic substitute for Milk.

"French President at the Font."

Leicester Daily Mercury.

Where he received his baptism of fire?

"German infantry on the morning of the 5th ventured an assault and were repulsed by blithering fire."—Pioneer.

Some of their Professors should be able to do good work in the blithering line.

"Reuter's agency learns that according to an official telegram received in London Turkish vessels have entered the open port of Odessa and bombarded Russian ships.

6 to 1 agst Cheerful, 7 to 1 agst Flippant."

South Wales Echo.

Not at all; we remain both.

WHAT OUR TAILOR HAS TO PUT UP WITH.

Scene I. A perfect fit.

Scene II. After a week's drill.

Fleet Street was thrilled to the depths of its deepest inkpot last week when it read in The Daily Chronicle of the historic meeting between Mr. Harold Begbie and MR. W. J. Bryan in New York. The sensation was caused not so much by the announcement that Mr. Bryan "has the long mouth of the orator, the lips swelling and protruding as he speaks, thinning and compressing when he is silent," or that "the full and heavy neck, which seems to be part of the face, is corded with muscles," although either of those statement is startling enough. Nor was it Mr. Begbie's struggle to decide whether he should devote his attention to the great statesman or to the railway station in which they met, the statesman being selected only just in time. No, what nearly stopped the clock of St. Bride's church was this paragraph in Mr. Begbie's record of the event: "At this point I asked quite innocently, and with a real desire for information, an obvious but indiscreet question, which Mr. Bryan rebuked me for asking, reminding me that he was a member of the Government."

What a subject for an Academy painting in oils! Or, if Milton had been living at this hour, how he would have immortalised the touching scene!

A desire to present to our readers some fuller details of this world-staggering event prompted us to cable to a few correspondents in New York. One cables back: "The scne was dramatic in the extreme. The journalist, his big blue eyes brimming with innocence, gently breathed the question, when the great statesman shook his shaggy many and roared out his rebuke like a lion in pain. The journalist's apologetic gesture was one of the most delicate things I have ever seen."

Another tells us:—"When Mr. Begbie put his question so great a stillness reigned throughout the crowded railway station that you could have heard a goods-train shunt. Mr. Bryan looked long and earnestly at the journalist, then, placing his hand affectionately on his shoulder, he said to him in a throbbing voice, 'Oh, Harold, how can you?'"

"The Incorrigibles."

"The enemy made attacks, but each effort was repulsed with great laughter."—Star.

"One recalls in this connection the statement made by Alexander the Great, that Napoleon's invasion of Russia was defeated not by the Cossacks, but by Generals January and February."—Stock Exchange Gazette.

This reminds us of Caesar's comment on the sack of Louvain:—"Magnificens est, sed non bellum."

Above the Adiniralty,

To take the news of seamen

Seafaring on the sea;

So all the folk aboard-ships

Five hundred miles away

Can pitch it to their Lordships

At any time of day.

Their crackling whispers go;

The demon says, "Your servant,"

And lets their Lordships know;

A fog's come down off Flanders?

A something showed off Wick?

The captains and commanders

Can speak their Lordships quick.

Look up above Whitehall—

E'en now, mayhap, he's taking

The Greatest Word of all;

From smiling folk aboard-ships

He ticks it off the reel:—

"An' may it please your Lordships,

A Fleet's put out o' Kiel!"

"Much indecision prevails as to what the value of sultanas will be in the near future."

Daily Telegraph.

What the Germans want to know is the price of Sultans.

War Gossip.

Park Lane.

Dearest Daphne,—The situation here is unchagned, though we have made some progress in knitting. Forgive me, m'amie, but one does get so into the despatch habit! The other day I'd a letter from Babs, in which she told me she'd "nothing fresh to report on her right wing" before she pulled herself together.

Norty's at the front as a flying-man. He's finding out all sorts of things, dropping bombs on Zeppelins and covering himself with glory. I had a few lines from him last week. He dated from "A place in Europe," (they have to be enormously cautious!), and said he was having the time of his life. He was immensely pleased with the last letter I managed to get through to him, and was particularly struck, he says, with my advice to him: "find out all you can, and above all don't get caught;" he considers it simply invaluable advice and says all airmen ought to have it written up in letters of gold somewhere or other.

Stella Calckmannan's had a fortnight's training as a nurse and is off. I ran in to see the dear thing the night before she left. She'd been posing to a photographer in her Red Cross uniform for hours and hours and was almost in a state of collapse; but the heroic darling said she was ready to do even more than that for her country. In one photo she's sitting by a cot with her hands folded, looking sad but very sweet. In another she'd standing up, singing, "It's a long way to Tipperary;" and in a third she's bandaging someone (she had one of the foormen in for this photo), and à mon avis, it's the least successful of all. She appears to be choking the poor man! However, they're immensely charming, and will all be seen in the "Aristocratic Angels of Mercy" page of next week's People of Position.

Dear Professor Dimsdale has only just got back to England from his eclipse expedition. I'm not sure now whether it was an eclipse or an occultation, but anyhow the only place where it could be properly seen was a mountain in the Austrian Tyrol. It was due in the middle of August, and the last week in July the Professor set off with his big telescope and his lenses and his assistants and his note-books and everything that was his. He lived a week or two on the mountain, to get used to the atmosphere and prepare all his things, so he didn't know what was going on in the world below. And then, just as the eclipse or whatever it was began, and the Professor was looking up at the sky for all he was worth, a lot of fearful creatures came rushing up the mountain and said there was a war and that he was an alien enemy and that he was making signals and that his big telescope was a new sort of howitzer; and they pushed him down the mountain, and broke his telescope and all his lenses, and tore up his notebooks, and shook their fists at him and used such language that he said for the first time in his life he was sorry he was such a good linguist!

They finished by shutting him up in a fortress, and there he's been ever sinse. He hardly knows how it was he got away, but he believes the whole garrison was marched off to meet the Russians, and that they're all prisoners now—which is his only drop of comfort. I've tried to console him for having missed what he went to see. I said, "Perhaps the eclipse or whater it was will happen again soon—or one like it." He groaned out, "My dear lady, that particular conjunction of the heavenly bodies will not occur again for 2,645 years, 9 months, 3 weeks and 2 days." So there it is, my dearest!

Would it cheer you up to hear a small romance of war and knitting? Here it is, then. Some time ago Monica Jermyn brought round some terrific mitts she'd knitted to go in one of my parcels for the troops. She'd easily the worst knitter who ever held needles! "My dear child," I said, "what simply ghastly mitts! They're full of mistakes." "What's it matter?" Monica answered. "Mistakes will keep them quite a warm as the right stitches. Besides, they're all right. I knit ever so much better now than when I used to make socks for the Deep Sea Fisherman last year." "That's not saying much," I said. "I remember those socks for the Deep Sea Fishermen, and I doubt whether even the deepest sea fishermen would know how to put them on! What's this?" "It's a message to go with the mitts," replied Monica. This was the message:—"The girl who made these mitts hopes they will be a comfort to some dear brave hands fighting for her and her sisters in England." "Oh, my dear!" I remonstrated. "It's very young and romantic of you, but don't you think it's just a little———" "No, I don't!" she cried. "And if it is, I don't care. Please, please let it go!" So it went.

Soon after that the Jermyns went down to their place in Sussex, and later I heard they'd some convalescent war heroes as guests. Monica wrote me: "All six of them are dear brave darlings, of course, but one of them is darlinger than the others. Tell it not in Gath, dear Blanche, but I think I've met my fate!" Later she wrote: "He's getting on splendidly. He turns out to be a cousin of the Flummerys. HE performed prodigies of valour, but won't say a word about it. When he leaves us my heart will quite, quite break—and I sometimes hope his will too!"

Yesterday came the following:—"Claude and I belong to each other. And what, oh what do you think helped to lead up to the dear, delicious finale? But wait. My hero is almost quite well now, and this morning, when we took what would have been our last little walk in the grounds, it happened! He walked beautifully now, though he still needs an arm at about the level of mine to lean on. It was a chilly morning and, as I was looking down and trying to think of something to say, I gave a suggen shriek, for on his dear heroic wrists I recognised—My Mitts! And when he heard I'd made them he was just as confondu as I was. 'They were in a bale of comfies sent to my company,' he said, 'and I had the ladling out of them to the men. But when I came to these mitts, with the sweet little message pinned to them, I simply couldn't part with them! And to think you made them—and wrote the little message! It makes one believe in all those psychic what-d'-you-call-'ems.'

"I felt a crisis was coming and so I said hurriedly, 'Oh, I only wish they were worthier of—of—brave hands and wrists. I'm a wretched knitter—they're full of mistakes—I kept forgetting to keep to the pattern—it ought to have been "knit two together and make one"—but of course you don't understand knitting.' 'I understand it right enough if that's all there is to it,' he said. '"Knit two together and make one." Monica—no, you mustn't run away———' And that's all you're going to be told, Blanche, except that the powers that be having given their consent and I'm too happy for words!"

Et voilà mon petit roman de guerre et de tricotage.

My poor Josiah is still at the uttermost edge of beyond. He began to come home, and the boat was chased and ran to an island for shelter, and then the island was taken by one of our enemies and he was a prisoner. Then it was retaken by one of th eAllies and he was free again. Since then more thangs have happened and he's been a prisoner again, and free again. And now he's lost count, and says he doesn't know what he is or who's got the island!

Ever thine,

Blanche.

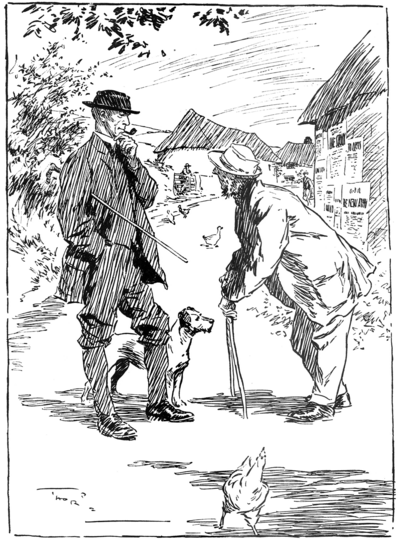

Cyclist. "Many recruits gone from this village?"

Shopkeeper. "No, Sir."

Cyclist. "Oh, why's that?"

Shopkeeper. "Well, Sir, after going carefully into the matter, we, in this neighbourhood, decided to remain absolutely neutral."

"Your moustache, too, is fiercer than mine;

But I'm tempted to ask by the size of your head,

Do you really suppose you're divine?"

That I held the most orthodox views;

But since I have hypnotized Harnack and Co.

I simply believe what I choose."

You you frequently talk through your hat;

For you told us the English were worthless in war;

Pray what was the reason of that?"

I studied that decadent race,

And in failing to prove that my forecast was true

They have covered themselves with disgrace."

Cries, Down with the humble and meek;'

Yet the sack of Louvain made your bosom to bleed;

Why were you so painfully weak?"

With a zeal that no force could restrain;

And the love of mankind which that study imparts

Has made me unduly humane."

That you're losing your grit and your fire;

And, if I may whisper the hint in your ear,

Don't you think that you ought to retire?"

"That might battle the wit of a Zancig;

I'm tired of your talk and I'm sick of your 'side':

Be off, or I'll send you to Danzig."

The Way of the Turk.

But the course she's resolved to pursue

Is true to her mind, which we constantly find

À l'Enver(s) et contre tous.

The Hun and the Tartar stand together—par mobile patrum."

Newcastle Daily Journal.

We cannot speak with equal confidence of the head of the Tartars, but the Kaiser certainly makes a very mobile parent.

Cavalry Instructor (to nervous Recruit). "Now then; none o' them Cossack stunts 'ere."

VII.

Dear Charles,—We haven't gone yet. Upon my word, we don't know what to do about it. We start off for the Continent and then we halt and ask ourselves, "Won't they be wanting us to go to Egypt and have a word with the enemy there?" So we come back and change our underclothes and start out again; but we haven't got far before a persistent subaltern starts a scare about invasions. At that we halt again and have a pow-wow. Thick underclothes for the Continent; thin underclothes for Egypt, but what underclothes for home defence? And that, old man, is the real difficulty about war: what clothes are you to make it in? Our official programme is, however, clearly defined how. It is this: We sail on or about ——— to ———, and thence to ———. We then change direction left and turn down by the butcher's shop and up past the post-office. Here we form fours, form two deep, slope arms, order arms, present arms, trail arms, ground arms, take up arms, pile arms, unpile arms, move to the right in fours, by the left, left wheel. The essence of these manœuvres is that they make it impossible for even the most acute enemy to guess which is our real direction. He gathers that it is one of two things: it is either right, or, failing that, left. But which? Ad, that is the secret! Sometimes I am in some doubt myself after having given the order.

Our musical repertoire is extensive, and, I venture to think, very aptly and poetically expresses the feelings of soldiers in the several aspects of military life. Their deep-seated respect for ceremonial is expressed thus, to the Faust airs:—

All soldiers eat it instead o' ham.

And every morning we hear the Colonel say,

'Form fours! Eyes right! Jam for dinner to-day!'"

His heart's sorrow upon leaving his fatherland is rendered exactly thus:—

We're going to cross the Ocean.

Good bye-er!

Fare-well-er!

Farewell for ever-mo-er!"

And lastly his deep concern for his country's and his own and everybody's welfare is thus put:—

It doesn't belong to me."

We had a Divisional Field Day yesterday. Recollecting a previous experience, the G.O.C. sent for his three Brigadiers, when the division was assembled for action, and, it seems, said to them, "There must be less noise." The Brigadiers, returning to the field, called out each his four battalion-commanders and said to them, distinctly, "There must be less noise." The twelve battalion commanders called out each his eight company-commanders, who called out each his four section-commanders, and in every instance was repeated, quite audibly, the same utterance, "There must be less noise." Three hundred and eighty-four section-commanders were engaged in impressing this order, with all the emphasis it deserved, upon the men, when the General rode on to the field. His anger was extreme. "There must be less noise!" said he.

Yours ever,

Henry.

"The Press also avoids very carefully all discussion of the status of the Goeben and a the the Breslau. Practically the only reference to the subject is a remark in the Frankfurter Zeitung that Turkey has alone to decide what ships are to fly under her flag."—Times.

If Turkey decides that the Goeben is to fly, we hope she will warn the man who works the searchlights at Charing Cross.

Able-Bodied Civilian (to Territorial). "THAT OUGHT TO GIVE YOU A GOOD LEAD, MATE."

Territorial. "YES—AND I MEAN TO TAKE IT! WHAT ABOUT YOU?"

A Prussian Court-painter earning an Iron Cross by painting pictures in praise of the Fatherland for neutral consuption.

By Toby, M.P.

"Lord Charles has broken his chest-bone—a piece of which was cut out in his boyhood leaving a cavity—his pelvis, right leg, right hand, foot, five ribs, one collar-bone three times, the other once, his nose three times." Thus Mr. Copy Cornford in one of the notes with which he illuminates the Memoirs of Admiral Lord Charles Beresford, published by Messrs. Methuen in two volumes, illustrated with a score of plates, the portrait of Lady Charles adding the charm of rare beauty to the collection.

For many years I have been honoured by the friendship of Lord Charles, and have had frequent opportunity of witnessing his multiform supremacy. Till I read this amazing catalogue of calamities, I never dreamt that among other claims to distinction he might have been billed as The Fractured Man, principal attraction in a travelling show, eclipsing the One-Legged Camel, the Tinted Zebra, and the Weird-Eyed Wanton from the Crusty North, who can sing in five languages "It's a Long, Long Way to Tipperary." Ignoring the monotony of experiences suffered by the ribs, and noting the obtrusiveness of one collar-bone, we may, with slight variation from a formula in use by the Speaker in the House of Commons, declare "The Nose had it." Happily no one regarding Lord Charles's cheery countenance would guess that its most prominent feature had been "broken three times."

Here is a man whose life should be written. Fortunately the task has been undertaken by Lord Charles himself, and the world is richer by a book which, instructive in many ways, valuable as throwing side-lights on the slow advance of the Navy to the proud position which it holds to-day on the North Sea, bubbles over with humour.

Record opens in the year 1859, when Lord Charles entered the Navy, closing just half-a-century later, when he hauled down his flag and permanently came ashore. Within the space of fifty years there is crammed a life of adventure richly varied in range. A man of exuberant individuality, which has occasional tendency to obscure supreme capacity, of fearless courage, gifted with a combination of wit and humour, Lord Charles is the handy-man to whom in emergency everyone looked not only for counsel but for help. It is a paradox, but a probability, that had he been duller-witted, a more ponderous person, he would have carried more weight alike in the councils of the Admiralty at Whitehall and of the nation at Westminster.

As these memoirs testify, behind a smiling countenance he hides an unbending resolution to serve the public interest, whether aboard ship or in his place in Parliament. Perhaps the most familiar incident in his professional career is his exploit during the bombardment of Alexandria, when the signal flashed from the flag-ship, "Well done, Condor." A more substantial service was his command of what he describes as "the penny steamer" Safieh, whose manœuvring on the Nile amid desperate circumstances averted from Sir Charles Wilson's desert column, hastening to the rescue of Gordon, the fate which earlier had befallen Stewart.

Another splendid piece of work was accomplished when, after the bombardment of Alexandria he was appointed Provost-Marshal and Chief of Police, and had committed to his charge the task of restoring order. His conspicuous success on this occasion bore fruit many years later when he was offered the post of Chief Commissioner of Police in the Metropolis. His story of the Egyptian and Soudan Wars, carried through several chapters, is a valuable contribution to history. It suggests that, all other avenues to fame closed against him, Lord Charles would have made an enduring name as a war correspondent.

It is a circumstance incredible, save in view of the authority upon which it is stated, that, as part of the reward for his splendid service in the Soudan, Lord Charles narrowly escaped compulsory retirement from the Service before he had completed the time required to qualify for Flag Rank. The Queen's Regulations ordained that before a captain could win this prized position he must have completed a period of from five to six years of active service. In 1892, Lord Charles, the flag almost in reach of his hand, applied for permission to count-in the 315 days he was strenuously and brilliantly at work in the Soudan. The Board of Admiralty, invulnerable in their environment of red tape, refused the request, repeating the non possumus when on two subsequent occasions the request was preferred.

It must be admitted that th eBoard had no reason to regard Lord Charles with favour or even with equanimity. When returned to Parliament, the man who had superintended the mending of the boiler on the penny steamboat on the Nile, devoted himself to the bigger task of mending the Navy, at that time in an equally pitiful condition. During his brief and solitary term of office as Junior Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Charles, who thought he was put there to do some work, drew up a memorandum on the necessity of creating at the Admiralty a Naval Intelligence Department. The memorandum was laid before the Board, and the Junior Lord was told he was meddling with high matters that did not come within the scope of his business. A few weeks later a Naval Intelligence Department (or a sort) was created. Sic vos non vobis.

'Twas ever thus. Lord Charles, whether in office, on active service, or from his familiar place above the Gangway in the House of Commons, bringing to bear upon Naval affairs the gift of keen intuition and the endowment of long practical experience, has, with one exception, done more than any many living to deliver the Navy from mistakes inevitable in the case of the over-lordship of a civilian who is subject to currents of political and party feeling. By way of reward he has received more kicks than ha'pence.

GERMANISED TURKEY.

"Dere you are, mein friendt; der same old flag mit a leedle difference."

I had secured an empty compartment. Something in my blood makes me rush for an empty compartment. I suppose it is because I am a Briton, yet it was another Briton who intruded upon my privacy.

At the first glance I saw that he would talk to me about the—well, what do you expect? I can always tell when men want to talk about it. Would that I had the same subtle instinct when they wish to borrow money! I was ready for him. If he said, "Have you heard?" I was going to answer, "About the Secretary of State for War ordering Lord Fisher to be imprisoned in the Tower as spy? Why, my brother-in-law told me all about it last week."

Instead he put his hand on my knee and asked, "Are you a German?"

"Unless I am descended from Hengist or Horsa," I replied, "there isn't an atom of culture in me."

"Then I can confide in you. A disturbance is advancing in this direction from Eastern Europe."

"You mean that the Crown Prince is retreating towards us from Poland?"

"No," he snapped. "And another disturbance is coming from the vicinity of Iceland."

"Good heavens! This is too much. At my time of life how am I to learn how to pronounce Pzreykajvik."

"Let me tell you what I prophesy for the next few days. Saturday will be bright."

"Splendid! A cheerful week-end will do us all good."

"Sunday will be gloomy, and on Monday will come the downfall."

"William's or ours?"

"Accompanied by strong south-westerly winds, rising to a gale, and a rapid fall of the barometer. So now you now. My mind is easy. I have told someone. I have been cruelly censored—only allowed to predict just wet or fine from day to day. I felt that I must tell someone. The Censor and Count Zeppelin between them were killing me."

I pitied the agony of the professional weather forecaster. I promised to respect his confidence. I left the crriage proud of the fact that I was one of the two men in England who knew what Saturday's weather would be. That is why I left my umbrella at home while apparently every other man took his out. It is also the reason why my new topper was ruined. And now I wonder whether the prophet was mistaken, or whether at the last moment he detected signs of culture in me and lied.

From an Indian paper:—

"The Germans are continuing the questionable tactics of sowing floating mines in neutral waters to the danger of neutral shipping, as well as of British and French war vessels. They are apparently tying them in Paris, so as to make it more difficult to avoid them."

As a result, the Iron Duke had had to give up entirely its morning run down the Rue de Rivoli. At the same time we are glad to hear that these floating mines are tied. It stops them from floating quite so much.

"No, Sir, they wouldn't take our Fred, 'cos they said he'd a-got bellicose veins."

(Note: If this essay in the well-informed manner achieves any success, the credit is largely due to the timely interruptions of the Censor.)

Few people, I think, realise the tremendous significance of waterproof overalls in a war like the present. I was talking to one of our most prominent Midland manufacturers at Sheringham the other day and he remarked confidentially [passage deleted by the Censor] at fifteen per cent. reduction to our soldiers for spot cash.

Which reminds me of a stifling Malta afternoon, when I first saw the good ship Sheringham steam slowly up through the haze of Sliema Creek. It was in the early days of the Navy's grey-paint era. The change was a drastic one, as all service-men admitted. And why grey? I make no secret of the fact that I have always advocated ultramarine for the Mediterranean station; but the Grey Water School, you know—well, there, I must not be indisercet.

Life on a cruiser may be the tally for some, but give me the nimble t.b.d.! There you have none of "the great monotony of sea" which drove W.M.T. to his five meals a day. Nothing but the charming fraternité of the wardroom, the delightful inconsequences of the chart-house kitten, and the throb of the oil-fed turbine! Unless I am greatly mistaken [passage deleted by the Censor which shows that I wasn't].

I was dining the other evening at the Buckingham Palace with a friend who is well known in Foreign Office circles. The conversation turned, naturally enough, on the dangers in our midst from foreign waiters. The English waiter who was attending us happened at the moment to dislodge with his elbow a wine-list which, in falling, decanted a quantity of Sauterne into the lap of my vis-à-vis, who remarked [passage deleted by the Censor].

I learn from reliable sources that one wing of our "contemptible little army' is resting upon ———. Dear old ———! How often have I wandered down your sleepy little High Street to the épicerie of our lively old Thérèse! But that was in the old days, before the black arts of Kaiserism transformed the peace of yesterday into the Armageddon of to-day. Next week I shall deal more intimately with life behind the scenes in German frontier towns; but you must wait with what patience you can for these further confidences.

With footsteps too cunning to swerve,

They swing through the heights of the jungle,

These stalwarts of infinite nerve;

Blithe sailors who heed not the breezes

Which play round their riggings and spars,

Lithe gymnasts who live on trapezes

And parallel bars.

They scamper, they slither and slide

In the throes of a tropical tango,

In the grip of a Gibbony glide;

'Tis thus in these desolate spaces,

Away from humanity's ken,

They mimic the civilised races

And strive to be men.

O'er creepers of myriad shapes,

They mouth not the meaningless chatter

Of dull and demoralised apes;

But, proud of their portion as creatures

Who know not the stigma of tails,

They screw up their weather-worn features

And practise their scales.

When I study some antic that hints

At the physical fitness of Sweden,

The speed of American sprints,

I dream of the wreaths and the ribbons

Their prowess would certainly win,

If there weren't any war, and my gibbons

Could go to Berlin.

J. M. S.

By a Voracious Reader.

All day long I read the papers that keep this little island noisy and tell us how we ought to be governed. I can't help it. I want to know the latest, and reading the papers seems (more or less) way to get at it. The best way of all, of course, is to meet a man at a club or a resident in a locality favoured by retired colonels; but, in default of those advantages, one must buy the papers. And then of course it follows that one reads far too many papers and gets one's head far too full of war news. Still, what would you have? The war is so eminently first and everything else nowhere that this is inevitable.

Outside suggestion has its share, too. Morning papers are a matter of course. One reads one's regular morning papers and no others. But after that the trouble begins with the evening paper placards, each with its lure. How can one resist them? The progress of the Allies! The repulsing of the enemy! The ten miles gained! The Russian advance! A German cruiser sunk! Each newsman has a different bait, and as the day goes on they become more attractive, so that one goes to bed at night filled with optimism. Well, these all have to be bought.

Speaking as a reader of too many of them I must admit to a grievance or two; and the chief is the difficulty that we have in finding the fulfilment of all the promises which are set out in the headings to the principal war news. For example, I find among these headings on the day on which I write a reference to a German admission of failure and dismay. But can I find the thing itself? I cannot. It may be there, but again and again has my eye travelled up and down the columns seeking the nutritious morsel and not yet has it alighted thereon, and that is but one case out of many. Sometimes after a long hunt I do track these joyful tit-bits down, and then discover that they are separated from the heading by several columns. Some day a newspaper editor will arise who can achieve a really useful index to his contents. The Times used to have something of the sort, but under the stress of battle that has gone.

Another grievance—but I shall say no more on that subject. Grievances are for peace time, when a general huffiness and stuffiness about the way that everyone else conducts business is natural and indeed expected. In war-time no one should be harassed by criticism. So I pass on to the paper which I like best of all those now being published. I like it because it contains the news I most want to read, and every day, or rather every night, it gets better and will continue to get better until the Brandenberg gate opens to let the Allies in. This paper is not a morning paper and not an evening paper. IT is published at night, in the smallest of the small hours, and I am its sole subscriber, for it is the paper of my dreams. Whether or not I am its editor I could not say. That question leads to the greater one which would need a volume for its decision: Do we compose our own dreams, or are they provided by Ole Luk Oie or some some other dream-spinner? Anyway, no one can read the paper of my dreams but I, and it is, after all, the best reading. It contains the oddest things. Last night it had a fine article about a football match in the North of England. Twenty-two terrific fellows, whose united salaries came to a respectable fortune and whose united transfer fees, should their Clubs every let them go, would be sufficient to build a Dreadnought, had been charging up and down the ground in a series of magnificent rushes, while ten thousand North of England lads roared themselves hoarse to see such glory. Suddenly a newspaper boy, reckless of his life, dashed on to the ground with a placard stating that a whole regiment of British soldiers had been trapped by a German ruse an annihilated. In an instant the game was broken up and every player and every spectator who was of age ran like hares to the nearest recruiting office and enrolled themselves as soldiers. They had seen in a flash that the only chance for England to get rid of this German menace was for every eligible man to do his share.

In another part of the paper I read of a young and powerful man in an English village who, on being asked if he did not think that England was in danger, replied "Yes." He was then asked if he did not think that it was necessary to fight for her, and he replied "Yes" again. He was then asked who in his opinion were the most suitable volunteers to come to her aid, and he replied, "Other people." So far the story is not appreciably different from a story that you might read anywhere. But the version in my paper stated that he was seized by all the company present and not only ducked in the nearest horse-pond but held under the water for quite a long time, and then held under the water again.

And another article—a most exciting one—described the success of a British aviator who flew over Essen and dropped five bombs on Krupp's gun factory and did irreparable damage. I forget his name, but, although he was pursued, he got clear away and returned to the Allies' lines. There was a fellow for you!

So you see that I get some good reading out of my favourite paper. And more is to come!

My guerdon after many toilsome days,

Shall gladden me no more. It was a sight

To bid men gape in wonderment, and praise

My patient courage that endured despite

The gibes of friends and Delia's pitying ways.

Ah, cruel fate that forced my hand to snip

Such cosily growth as graced my upper lip!

That let their lush growth riot as it will,

With just a formal waxing now and then,

Did I maintain it. Nay, with loving skill

And all the precious oils within the ken

Of cunning alchemists I strove until

Its soaring points aspired to pierce the skies,

And I was martial in my Delia's eyes.

To one that works in metals and I bought

A kind of dreadful iron instrument

With leathern straps, most wonderfully wrought,

And wore that horror nightly, well content

To bear such anguish for the prize I sought.

And all this patient toil was thrown away—

They stoned me for the Kaiser yesterday!

At a time when every penny that can be spared is needed for the help of our soldiers in the field and of our wounded, or to relieve the distress of the Belgian refugees or our own sufferes from the War, a public appeal is being made to the citizens of Newcastle-on-Tyne for subscriptions to a fund for presenting a testimonial to their Lord Mayor, on the ground that he has done his duty. We beg to offer our respectful sympathy to the Lord Mayor of Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Colonel of Swashbucklers. "Nah then, Swank! The wimmin can look arter theirselves. You'op it and jine yer regiment."

I had done the second hole (from the vegetable-marrow frame to the mulberry-tree) in two, and was about to proceed to the third hole by the potting-shed when I thought I would go in and convey the glad news to Joan. I found her seated at the table in the breakfast-room with what appeared to be a heap of tea spread out upon a newspaper in front of her. Little slips of torn tissue-paper littered the floor, and on a chair by her side were several empty cardboard boxes. The sight was so novel that I forgot the object of my errand.

"What's all that tea for, and what are you doing with it?" I asked.

"It isn't tea; it's tobacco," Joan replied, "and I'm making cigarettes for the soldiers at the front."

"Where on earth did you get that tobacco from, if it is tobacco?" I went on.

"Let me see now," mused Joan, pausing to lick a cigarette-paper—"was it from the greengrocer's or the butcher's? Ah! I remember. It was from the tobacconist's."

Joan gets like that sometimes, but I do not encourage her.

"But what made you choose this Hottentot stuff?" I enquired.

"The soldiers like it strong," Joan replied, "and this looked about the strongest he'd got."

"What does it call itself?"

"It was anonymous when I bought it, but you'll no doubt see its name on the bill when it comes in."

"Thanks very much," I said. "That's what I should call forcible fleecing. Not that I mind in a good cause———"

"Isn't it ingenious?" interrupted Joan. "You just put the tobacco in between the rollers, and twiddle this button round until—until you've twiddled it round enough; then you slip in a cigarette-paper—like that—moisten the edge of it—twiddle the button round once more—open the lid—and shake out the finished article—comme ça!"

An imperfect cylindrical object fell on to the floor. I stooped to pick it up and the inside fell out. I collected the débris in the palm of my hand.

"How many of these have you made?" I asked.

"Only three thoroughly reliable ones, including that one," she replied. "I've rolled ever so many more, but the tobacco will fall out."

"Here, let me give you a hand," I suggested. "I'll roll and you lick."

"No," said Joan kindly but firmly. "You don't quite grasp the situation. I want to do something. I can't make shirts or knit comforters. I've tried and failed. My shirts look like pillow-cases, and anything more comfortless than my comforters I couldn't imagine. I wouldn't ask a beggar to wear an article I had made, much less an Absent-Minded Beggar."

"What about that tie you knitted for me last Christmas?" I said.

"Yes," said Joan; "what about it? That's what I want to know. You haven't worn it once."

It was true, I hadn't. The tie in question was an attempt to hybridise the respective colour-schemes of a tartan plaid and a Neapolitan ice.

"That," I explained, "is because I've never had a suit which would set it off as it deserves to be set off. However, if I can't help I won't hinder you. I only came in to say that I had done the second hole in two. I thought you would like to know I had beaten bogey." And I retired, taking with me the little heap of tobacco and the hollow tube of paper.

When I reached the seclusion of the mulberry-tree I found that the paper had become ungummed, so I placed the tobacco in it and succeeded after a while in rolling it up. The result, though somewhat attenuated, was recognisably a cigarette. I lit it, and when I had finished coughing I came to the conclusion that if only I could induce Joan to present her gift to the German troops instead of to our Tommies it would precipitate our ultimate triumph. I had to eat several mulberries before I felt capable of proceeding to the third hole. When I got there (in two) I found it occupied by a squadron of wasps while reinforcements were rapidly coming up from a hole beneath the shed. Being hopelessly outnumbered I contented myself with a strategical movement necessitating several stiff rearguard actions.

*****

Joan, growing a little more proficient, had in a couple of days made 500 cigarettes. I had undertaken to despatch them, and one morning she came to me with a neatly-tied-up parcel.

"Here they are," she said; "but you must ask at the Post Office how they should be addressed. I've stuck on a label."

I went out, taking the parcel with me, and walked straight to the tobacconist's.

"Please pack up 1,000 Hareems," I said, "and post them to the British Expeditionary Force. Mark the label 'Cigarettes for the use of the troops.' And look here, I owe you for a pound of tobacco my wife bought the other day. I'll square up for that at the same time. By-the-by, what tobacco was it?"

"Well, Sir," the man replied, "I hardly like to admit it in these times, but it was a tobacco grown in German East Africa. It really isn't fit to smoke, and is only good for destroying wasps' nests or fumigating greenhouses, which I thought your lady wanted it for, seeing as how she picked it out for herself. Some ladies nowadays know as much about tobacco as what we do."

I left the shop hurriedly. The problem of the disposal of Joan's well-meaning gift was now solved. I returned home and furtively stole up the side path into the garden. Under cover of the summer-house I undid the parcel and proceeded rapidly to strip the paper from those of the cigarettes that had not already become hollow mockeries. When I had collected all the tobacco I went in search of the gardener, and encountered him returning from one of his numerous meals.

"Wilkins," I said, "there is a wasps' nest on the third green, and here is some special wasp-eradicator. Will you conduct the fumigation?"

As Joan and I were walking round the garden that evening before dinner Joan said—

"I don't want to blush to find it fame, but—do you know—I prefer doing good by stealth."

A faint but unmistakable odour was borne on the air from the direction of the third green.

"So do I," I said.

My wife attributes our success (so far) in the entertainment of Belgian Refugees solely to the fact that we have not, and never have had, a vestige of a committee. We all work along in the jolliest possible way, and we have no meetings, or agenda, or minutes, or co-opting of additional members, or remitting to executives or anything of that kind. We just bring along anything that we think will be useful. Some of us bring clothes and others butter or umbrellas, or French books, or razor-strops or cigarettes. Hepburn, the dairy farmer, keeps sending cart-loads of cabbages; old Miss Mackintosh at the Brae Foot sends threepence a week. And when we are short of anything we just stick up a notice to that effect in the village shop. I issued a call for jam yesterday and ever since it has rained pots and pots. We have three large families of Belgians and we have already got to the stage where the men are at work and the children at school—though no one really has the least idea what they do there.

But although I admit that it is magnificent to be without a committee—we escaped from that by the simple plan of getting the Belgians first and trusting to the goodwill of the Parish to take care of them afterwards—there are other important factors in our success. There is our extraordinary foresight—of course it was a pure fluke really—in obtaining among them a real Belgian policeman. You can have no idea what a fine sense of security that gives us in case anything goes wrong. We have already enjoyed his assistance in a variety of ways, and we have something still in reserve in the very unlikely event of being professionally called in—his uniform. When we put him into his uniform the effect will be tremendous.

Then again we have the advantage of being Scotch. I simply don't know how English country people are going to get on at all. Here we find that by talking with great emphasis in the very broadest Scotch—by simply calling soap sape and a church a kirk you can quite frequently bring it off and make yourself understood. I had a most exhilarating hour of mutual lucidity with the one that makes furniture in the carpenter's shop. It seemed to me that he called a saw a zog, which was surely quite good enough; and when he referred to a hammer as a hamer it might surely be said to be equivalent to calling a spade a spade.

Still the language difficulty remains, and the worst of it is that it gives an altogether unfair advantage—where all are so anxious to help—to the few select people in our neighbourhood who happen to be able, fortuitously, to talk French. They are—(1) Dr. Anderson, whose French is very good; (2) my wife, who is amazingly fluent in a crisis, though her constructions simply don't bear thinking of; (3) the school-master, who is weak; (4) the joiner, who is bad; (5) myself, who am awful. Several of our Refugees talk French.

Of course we all have pocket-dictionaries, but even they don't always help us out. I found my wife once engaged in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter with the one who does the cooking about some household necessity that was sadly lacking. She was completely baffled. It was pure stalemate, a deadlock. I pulled out my dictionary and suggested to the cook (by illuminative signs) that she should look it up and point to the English word. There was some rejoicing at this, and she at once called upon the collective wisdom of her whole family. At last they got it with much nodding of heads and exhibited the book, buttressed with an eager finger at the place. And we looked and read "A young goldfinch;" so you will see that that didn't help us much. It was only by the almost miraculous emergence of the word Fat in the course of their own private conversation shortly afterwards that light came to us.

That they are quite at a loss to understand the meaning of honey in the comb did not greatly surprise us—though it was rather queer—but the Parish is deeply distressed at their total ignorance of oatmeal. They are quite at sea there, and so far have only employed it for baiting a bird-trap: and that touches us closely, for the very foundation of our being in these parts is oatmeal. Even their beautiful devotion to vegetables of all sorts cannot, we feel, compensate for their attitude of negation towards this very staple of existence. There is a strong party among us bent on their conversion. We hope with all our hearts that they will be comfortable and contented among us till the day comes when they can return to their own country; and we feel that their exile will not have been entirely wasted if they have learned to appreciate the purpose fulfilled by porridge in the Divine Order of things.

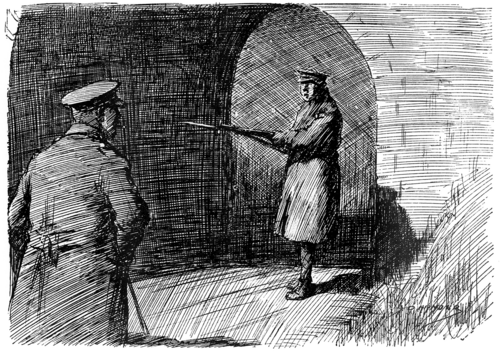

Sentry (on duty for first time). "'Alt! Who goes there? Advance to within five paces, and give the countersign 'Waterloo.'"

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

In the good old days when that royal pipsqueak, our First James, came to the throne, if you were a physician of a little more than common skill and furnished with theological opinions of a modernist complexion, or a lonely woman with (or without) some cunning in the matter of herbs, who cherished a peculiar (or normal) pussy-cat, you were quite likely to be burnt out of hand. And, in her competent way, Mary Johnston, in The Witch (Constable), deals with this dark blot on the escutcheon of Christianity. Through what suffering and what joys Dr. Aderhold, the kindly free-thinking mystic, and Joan Heron, the simple village maid, found their ultimate and, for the times, merciful release by halter in place of fire, readers who have nerves to spare for horror will read with eagerness. It is indeed a dreadful story. Miss Johnston is not one of your novelists who lets herself off the contemporary document, and on her reputation you may take it she is not far out. The grim tale serves to show to what lengths the force of suggestion will, in times of excitement, carry folk otherwise sober and truthful. Manifestly preposterous evidence, freely given, was freely admitted by trained legal minds—evidence on which innocent lives were sacrificed at the average rate of over a thousand a month in England and Scotland in the two centuries of the chief witch-baiting period. But, after all, have we not, most of us, near relations who saw a quarter-of-a-million of astrakanned Russians steal through England in the dead of an August night? And have we not——— But I grow tedious. The Witch is an eminently readable story of adventure of the coincidental kind.

What I like best in the stories of Mr. W. W. Jacobs, apart from their mere hilarity, is their triumphant vindication of the right to jest. They spread themselves before me like a pageant representing the graceful submission of the easy dupe. They tempt me to filch away chairs from beneath stout and elderly gentlemen who are about to sit down. Take the case of Sergeant-Major Farrer in Night Watches (Hodder and Stoughton). He was afraid of nothing on earth, or off it, but ghosts, and he despised the weedy young man who was in love with his daughter. So the weedy young man dared him to come to a haunted cottage at midnight, and, dressed up as a spectre, terrified the soldier into something more than a strategic retreat, with the result that he surrendered his daughter. In real life of course it is different. I know a colour-sergeant, and somehow I rather think that if I—but never mind. In Mr. Jacobs' beautiful world, as it is with Mr. Farrer so is it with Peter Russet, with Ginger Dick and with Sam Small. They know when the laugh is against them, and, waiving the appeal to force or to law, they grumble but retire. There is one exercise in the gruesome in Night Watches, but it hardly shows Mr. Jacobs at his best in this particular vein. There are also several charming illustrations by Mr. Stanley Davis, executed with a buff tint, which help to sustain the gossamer illusion.

If I were a woman I should always be a little irritated with any story which shows two women in love with the same man. Miss May Sinclair in her new novel does not mind how much she annoys her own sex. She shows us no fever than three women engaged in this competition, and they are sisters. True, there was not much choice for them in their lonely moorland village, which contained a young doctor and no other eligible man. Of this fellow Rowcliffe we are told that "his eyes were liable in repose to become charged with a curious and engaging pathos," an attraction which had broken many hearts before the story opened, and gave to their owner a great sense of confidence in himself. This set me against him at the start, but the three sisters, as I said, were not in a position to be fastidious. Mary's love for him was of the social-domestic kind; Gwenda's was spiritual; Alice's frankly physical. Though alleged to be "as good as gold," Alice, the youngest of The Three Sisters (Hutchinson), was one of those hysterical women who threaten to die or go mad unless they get married—a very unpleasant fact for a young doctor to have to discuss with her sister, and for us to read about. Indeed, if I were to tell in all its incredible crudity the story of the relations of this gently-bred girl with the drunken farmer who, to her knowledge, had previously betrayed her own servant-girl, I think even Miss Sinclair would be revolted. Her exposure of certain secret things which common decency agrees to leave in silence is a treachery to her sex, not excusable on grounds of physiological interest; and I, for one, who was loud in my praise of the fine qualities of her great romance, The Divine Fire, confess to a sense of almost personal sorrow that such high gifts as hers, which still show no trace of decline in craftsmanship, should have suffered so much taint. I sincerely hope that the noble work she is now doing with the Red Cross at the front—where the best wishes of her many friends follow her—may make more clear the claim that is laid upon her to devote her exceptional powers as a writer to the higher issues of life and death; or, at the least, to something cleaner and sweeter than the morbid atmosphere of her present theme.

It has been my private conviction that the most depressing and shuddersome of all natural prospects is the wide expanse of mud and slime to be found at low water in the estuary of a tidal river. Such scenes have always been singularly abhorrent to me. Mr. "Adrian Ross" appears to share this feeling, for out of one of them he has made the novel and very effective setting for his bogie-tale, The Hole of the Pit (Arnold). It is a story of the Civil Wars, though these have less to do with the action than the uncivil and very gruesome war waged between the Lord of Deeping Castle and the Unseen Thing that lived in the Pit. The Pit itself is real joy. It was covered always by the tide, but could be distinguished by a darker shadow on the surface of the sluggish stream, a shadow streaked at times by wavering bands of greyish slime, strangely agitated... There were smells, too, dank, sodden, drowned smells that came in upon the sea mist. Moreover, Deeping Castle I can only describe as an eligible residence for the immortal Fat Boy. It was built right upon the water, within convenient distance, as the auctioneers say, of the Pit; and between the two of them your flesh is made to creep more than you would believe possible. As for the great scene where the Thing finally gets out of the Pit, and comes slobbering and sucking round the castle walls—I cannot hope to convey to you the horror of it. Perhaps you may feel with me that Mr. Ross has been at times a little too confident that the undoubted thrill of his bogie would save it from being unintentionally funny. I confess I did laugh once in the wrong place. But everywhere else I shivered with the fearful joy that only the best in this kind can produce.

I remember that I have before this admired the mixture of cheerful cynicism and dry humour that is the speciality of Mr. Max Ritternberg. He has shown it again in Every Man His Price (Methuen), but hardly, I think, to quite the same effect as formerly. My feeling about the book was that it started with a first-class idea for a plot of comedy and intrigue, but that the author, instead of being contented with this, wanted to give us a novel of character-development on the grand scale, and somewhat spoilt his work in the attempt. The earlier chapters could hardly have been better. There was a real snap in the struggle between the English hero, Hilary Warde, who had nearly perfected a system of wireless telephony, and the Berlin magnates who wished to bluff him out of the results. As I say, I liked these early scenes and some others subsequently that dealt with rather sensational finance (it always cheers me up when the hero makes half-a-million pounds in a single chapter!) better than those that had to do with Warde's domestic entanglements and the deterioration of his character. And the climax seemed inadequate to the point of bathos. But there is much in the tale to enjoy; and you might read it if only for a vivid word-picture of what Berlin used to be like before the beginning of the great debacle. This has now an interest almost historical.

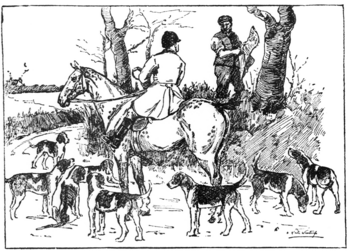

Hedger. "There's awful accounts in this 'ere paper of they Germans—seems there's some people as don't 'old nothing sacred."

Huntsman. "Ah! you may say so! And it ain't only Germans. Only last night I found as fine a dog-fox as ever I see with a bullet-wound through 'is 'eart!"

"TURKISH AMBASSADOR LEAVES BORDEAUX.

The Turkish Ambassador left Paris yesterday on a visit to Biarritz. He announced before leaving that he would return. This was the first visit paid by the Turkish Ambassador for over a fortnight. He did not see Sir Edward Grey, but had a long conference with Sir Arthur Nicolson, Permanent Under-Secretary."

Edinburgh Evening News.

The only possible answer to this extraordinary conduct was a declaration of war.