Seven Pillars of Wisdom

This work is incomplete. If you'd like to help expand it, see the help pages and the style guide, or leave a comment on the talk page. |

The text of this work has been migrated to Index:The Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926).djvu where it still requires clean up, formatting, and/or proofreading. If you would like to help, please see Help:Proofread. |

Seven Pillars

of

Wisdom

a triumph

1926

To S.A.

I loved you, so I drew these tides of men into my hands

and wrote my will across the sky in stars

To earn you Freedom, the seven pillared worthy house,

that your eyes might be shining for me

When we came.

Death seemed my servant on the road, till we were near

and saw you waiting:

When you smiled, and in sorrowful envy he outran me

and took you apart:

Into his quietness.

Love, the way-weary, groped to your body, our brief wage

ours for the moment

Before earth's soft hand explored your shape, and the blind

worms grew fat upon

Your substance.

Men prayed me that I set our work, the inviolate house,

as a memory of you.

But for fit monument I shattered it, unfinished: and now

The little things creep out to patch themselves hovels

in the marred shadow

Of your gift.

Mr. Geoffrey Dawson persuaded All Souls’ College to give me leisure, in 1919-1920, to write about the Arab Revolt. Sir Herbert Baker let me live and work in his Westminster houses.

The book so written passed in 1921 into proof: where it was fortunate in the friends who criticised it. Particularly it owes its thanks to Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Shaw for countless suggestions of great value and diversity: and for all the present semi-colons.

It does not pretend to be impartial. I was fighting for my hand, upon my own midden. Please take it as a personal narrative, pieced out of memory. I could not make proper notes: indeed it would have been a breach of my duty to the Arabs if I had picked such flowers while they fought. My superior officers, Wilson, Joyce, Dawnay, Newcombe and Davenport could each tell a like tale. The same is true of Stirling, Young, Lloyd and Maynard: of Buxton and Winterton: of Ross, Stent and Siddons: of Peake, Hornby, Scott-Higgins and Garland: of Wordie, Bennett and MacIndoe: of Bassett, Scott, Goslett, Wood and Gray: of Hinde, Spence and Bright: of Brodie and Pascoe, Gilman and Grisenthwaite, Greenhill, Dowsett and Wade: of Henderson, Leeson, Makins and Nunan.

And there were many other leaders or lonely fighters to whom this self-regardant picture is not fair. It is still less fair, of course, like all war-stories, to the un-named rank-and-file: who miss their share of credit, as they must do, until they can write the despatches.

Cranwell. 15. 8. 26 T. E. S.

Half-way through the labour of an index to this book I recalled the practice of my ten years’ study of history; and realised I had never used the index of a book fit to read. Who would insult his “Decline and Fall,” by consulting it just upon a specific point?

I am aware that my achievement as a writer falls short of every conception of the readable: but surely not so far as to make it my duty, like a Stubbs, to save readers the pain of an unnecessary page. The contents seem to me adequately finger-posted by this synopsis.

INTRODUCTION

THE FOUNDATIONS OF ARAB REVOLT

Some Englishmen, of whom Kitchener was chief, believed that a rebellion of Arabs against Turks would enable England, while fighting Germany, simultaneously to defeat her ally Turkey. Their knowledge of the nature and power and country of the Arabic-speaking peoples made them think that the issue of such a rebellion would be happy: and indicated its character and method. So they allowed it to begin, having obtained formal assurances of help for it from the British Government. Yet none the less the rebellion of the Sherif of Mecca came to most as a surprise, and found the Allies unready. It aroused mixed feelings and made strong friends and enemies, amid whose clashing jealousies its affairs began to miscarry.

- Chapter 1.—The strained mentality of rebellion (3) which infected me (4) and still, a year afterwards, prevents my judgement (6).

- Chapter 2.—Arabia and the Arabs (7) emigrations, immigrations, and the current of tribal movements (9) sessile or nomad (10).

- Chapter 3.—The uncompromising Semite (12) religious invention (13) his prophets (13) his creeds (14) his fanaticism (17).

- Chapter 4.—Arab decay (19) nationalism (20) secret societies (21).

- Chapter 5.—Sherifs of Mecca (24) the Holy War (25) thoughts of rebellion (26) Feisal and Jemal (27) Enver (28) the revolt (29).

- Chapter 6.—The decay of Turkish imperialism (30) a new factor required (32) Clayton's Arab Bureau (32) Mesopotamia (34).

- Chapter 7—The McMahon negotiations (37) his difficulties with his colleagues (37) my private difficulties (39) an escape (40).

BOOK I

MY FIRST VISIT TO ARABIA

I had believed these misfortunes of the Revolt to be due to faulty leadership, or rather to the lack of leadership, Arab and English. So I went down to Arabia to see and consider its great men. The first, the Sherif of Mecca, we knew to be aged. I found Abdulla too clever, Ali too clean, Zeid too cool. Then I rode up-country to Feisal, and found in him the leader with the necessary fire, and yet with reason to give effect to our science. His tribesmen seemed sufficient instrument, and his hills to provide natural advantage. So I returned confidently to Egypt, and told my chiefs how Mecca was defended not by Rabegh, but by Feisal in Jebel Subh.

- Chapter 8.—The Lama arrives at Jedda (41) Colonel Wilson welcomes Storrs and myself (42) Emir Abdulla (43) Arab government (44) military situation (45) Storrs persuasive (47).

- Chapter 9.—Jeddah (48) a dinner party (50) the Turkish band (51).

- Chapter 10.—Emir Ali at Rabegh (52) we ride inland (54) the Tehama and a discussion of water supplies as affecting Arab strategy (56) encounter at a well (57) tricks of a Sherif (58).

- Chapter 12.—Hills of Hejaz (60) Bir el Sheikh (61) highlands by night (62) a spy gives us food (63) a watered village (65).

- Chapter 13.—Slave economy (66) a ruined village (67) the rebels (67) my first meeting with the Emir Feisal at Hamra (68).

- Chapter 14.—Egyptian troops (69) Feisal's story of his first outbreak in Medina (70) his plans for the moment (73) himself (74).

- Chapter 15.—A political dinner (76) the royal family of Hejaz (76) nationalism among nomads and townsmen (77) religion (79).

- Chapter 16.—Playing the reporter (80) the troops and their native way of fighting (81) the situation (82) artillery (83) envoi (84).

- Chapter 17.—The ruined road (85) in Wadi Yenbo (86) Yenbo, Boyle, and hats (87) Admiral Wemyss (88) Khartoum, where we argue the Arab Revolt with Sir Reginald Wingate (89). a French idea (89) Sir Archibald Murray (90) I am good (91).

BOOK II.

FEISAL'S FIRST EXTENSION NORTHWARD

My chiefs were astonished at such favourable news, but promised help, and meanwhile sent me back, much against my will, into Arabia. I reached Feisal's camp on the day the Turks carried the defences of Jebel Subh. By their so doing the entire basis of my confidence in a tribal war was destroyed. We havered for a while by Yenbo, hoping to retrieve the position: but the tribesmen proved to be useless for assault, and we saw that if the Revolt was to endure we must invent a new plan of campaign at once. This was hazardous, as the promised British military experts had not yet arrived. However, we decided that to regain the initiative we must ignore the main body of the enemy, and concentrate far off on his railway flank. The first step towards this was to move our base to Wejh: which we proceeded to do in the grand manner.

- Chapter 18.—Clayton sends me back (93) Garland (93) Yenbo (95)

- Chapter 19.—Sherif Abd el Kerim's riding manners (96) a surprise on our road (97) Feisal's explanation of his move (98).

- Chapter 20.—Feisal's control (101) life at Arab headquarters (102).

- Chapter 21.—My new clothes (105) return to Yenbo (106) a defeat (107) treachery, perhaps (108) defending our base (109).

- Chapter 22.—Conflicting policies (111) French and English (112) the military situation develops (113) Wilson gambles on it (114).

- Chapter 23.—Feisal prepares to move on Wejh (116) troops for his expedition (117) a test raid (118) the Emir Abdulla (119).

- Chapter 24.—The army marches (120) naval politics (121) civil v. military (122) evacuation of Yenbo (123) my relief (124) Boyle at Um Lejj (124) Wejh plans (125) too forward (125).

- Chapter 25.—Feisal's staff (126) the routine of a march (127) Ageyl (128) Newcombe overtakes us (130) the route (131).

- Chapter 26.—Our units (133) good news (135) Wadi Hamdh (139)

- Chapter 27.—Reinforcements pour in (139) the Navy again (141).

- Chapter 28.—Boyle's victory (143) we re-organise Wejh (144).

BOOK III.

CONCENTRATING AGAINST THE MEDINA RAILWAY.

Our taking Wejh had the wished effect upon the Turks, who abandoned their advance towards Mecca for a passive defence of Medina and its Railway. Our experts made plans for attacking them. The Germans saw the danger of envelopment, and persuaded Enver to order the instant evacuation of Medina. Sir Archibald Murray begged us to put in such a sustained attack as should destroy the retreating enemy. Feisal was soon ready in his part; and I went off to Abdulla to get his co-operation, On the way I fell sick and while lying alone with empty hands was driven to think about the campaign. Thinking convinced me that recent practice had been better than our theory. So on recovery I did little to the Railway, but went back to Wejh with novel ideas. I tried to make the others admit them, and adopt deployment as our ruling principle; and to put preaching even before fighting. They preferred the limited and direct military objective of Medina. So I decided to slip off to Akaba by myself on test of my own theory.

- Chapter 29.—Rewards of victory (145) the need of guns (145) Jaafar Pasha takes command (146) Brémond's proposal (147).

- Chapter 30.—Life at Wejh (149) armoured cars and navy (151).

- Chapter 31.—The general war (152) political work (152) Feisal's propaganda (153) and the quality of his achievement (155).

- Chapter 32.—Clayton's bombshell (156) new dispositions (157) journey inland (157) sickness (160) a death for a death(161).

- Chapter 33.—In the hills (162) lava and volcanoes grown cold (163) implacable hospitality (164) Emir Abdulla's camp (166).

- Chapter 34.—Generalising the military theory of our revolt (167).

- Chapter 35.—Recovery (177) projecting a raid (178) a shepherd (180) fresh plans (181) mine-laying (182) a show (183).

- Chapter 36.—Shakir's triumph (184) another raid (185) a storm (186) mine-laying (187) the alarm (189) getting away (191).

- Chapter 37.—Emir Abdulla, nature and life (193) Shakir (195).

- Chapter 38.—Starting for Wejh (197) Beduin characters (198).

- Chapter 39.—Feisal again (202) Auda abu Tayi (203) the ruling strategy (205) my criticisms (206) the Akaba scheme (207).

BOOK IV.

THE EXPEDITION AGAINST AKABA.

Sherif Nasir, Auda, and I set off together for Akaba. Hitherto Feisal had been the public leader; but his remaining in Wejh threw the ungrateful load of this northern expedition upon myself. I accepted it and its dishonest implication as our only means of victory. We tricked the Turks and entered Akaba with good fortune.

- Chapter 40.—Our start (209) ourselves (209) Sherif Nasir and his great worthiness (211) a hill-garden (212) interlude (213).

- Chapter 41.—Arabic speech (214) our assumptions (215) a pause which relieves my weariness (217) two new men (218).

- Chapter 42.—Off again (219) Auda as guide (220) night (221) volcanoes, lava, dry mud and sand (222) camel sickness (224).

- Chapter 43.—Crossing the railway (225) into the real desert (227) a hot wind (228) the refreshment of night-fall, after (229).

- Chapter 44.—A new day (230) camels (232) ostrich and oryx (233).

- Chapter 45.—A man missing (234) alone (235) a joke overworked (237) we win across into Sirhan (238) the power of thirst (238).

- Chapter 46.—The new wells (239) an alarm (240) we arrive (244).

- Chapter 47.—We taste the full measure of Beduin hospitality (245).

- Chapter 48.—With the tribes (250) snakes (251) recruits (253).

- Chapter 49.—Over-vaulting ambition (254) true objective (255) false starts (256) my dilemma (257) a footnote to history (257) unwelcome power (258) the last feast (258) small-talk (259).

- Chapter 50.—On the road (262) dynamite (264) a poor job (265)

- Chapter 51.—A diversion to draw the Turks' notice (267) ambush (269) deserters (270) Zaal's power and my self-denial (271).

- Chapter 52.—A prisoner (273) the temptation of fresh meat proves fatal to a fat station-master (274) we surfeit ourselves (275).

- Chapter 53.—The King's well (276) action (278) calculation (279) many bridges taken and at once blown up (279) check (280).

- Chapter 54.—To the rescue (281) hot fighting (282) a gallop (283) camel-charging (284) prisoners (286) exploiting victory (287).

- Chapter 55.—After the battle (288) the dead (289) the crest (290) more victory (290) the last barrier (291) divided counsels (292) the enemy capitulate (293) we regain our familiar sea (293).

BOOK V.

EXPLOITING THE NEW BASE.

Our capture of Akaba closed the Hejaz war, and gave us the task of helping the British invade Syria. The Arabs working from Akaba became virtual right wing of Allenby's army in Sinai. To mark the changed relation Feisal was transferred, with his Army, to Allenby's command. Allenby now became responsible for his operations and equipment. Meanwhile we organised the Akaba area as an unassailable base, from which to hinder the Hejaz Railway.

- Chapter 56.—The sense of victory (295) assuring Akaba (296) to Egypt for help (297) the Inland Water Board carries on (298).

- Chapter 57.—Lyttleton (299) the permit police in the canal zone (300) naval help (301) Allenby (302) two schools (303).

- Chapter 58.—The organisation of Akaba (304) guardships (305) transfer of Feisal and all his troops (305) King Hussein agrees to it (306) palliating secret relations with the enemy (307).

- Chapter 59.—A new situation (309) changing methods (309) the invasion of Syria (310) the varied peoples composing Syria (310).

- Chapter 60.—The towns of Syria (314) Syrians (316) Syrian politics (317) our strategy (318) tactics (319) our spirit (320).

- Chapter 61.—Operations begin (322) air raids distract the enemy (323) electric mining (324) guns and Lewis guns (325).

- Chapter 62.—Project of a railway raid (326) points of character (327) tribal politics (329) the Turkish air patrol (330).

- Chapter 63.—Rumm, a tribal watering place in the hills (331).

- Chapter 64.—Seeking help (335) a bath (336) excursion into the origins of Christianity (337) an inarticulate prophet (339).

- Chapter 65.—We march (340) getting together (341) a rich drink by night, and a change of mind (343) reconnaissance (343).

- Chapter 66.—Modesty (344) mining (345) a Turkish patrol (347).

- Chapter 67.—The Turks threaten us (348) a train comes (348) and stops (349) ten minutes (350) booty (351) prisoners (352).

- Chapter 68.—Confusions (353) evacuation (354) rescue (355) a clean get-away in heavy order (356) Rumm by night (358).

- Chapter 69.—A training raid (359) obligations of command (360) success (361) and its fruit (362) what we were trying at (363).

BOOK VI.

THE FAILURE OF THE BRIDGES.

By November, 1917, Allenby was ready to open a general attack against the Turks along his whole front. The Arabs should have done the same in their sector: but I was afraid to put everything on a throw, and designed instead the specious operation of cutting the Yarmuk Valley Railway, to throw into disorder the expected Turkish retreat. This half-measure met with its due failure.

- Chapter 70.—Allenby takes the stage (365) his staff (365) our proper role (367) my private hesitation and its reasons (368).

- Chapter 71.—An unworthy choice (369) Sherif Ali ibn el Hussein (370) Abd el Kadir (371) a questionable adherent (372).

- Chapter 72.—New retainers (373) old retainers (374) Lloyd and Wood (375) our caravan gets off, but offers lamely (376).

- Chapter 73.—A Sherari finds a job and finds himself (377) a night march (379) the railway (380) Auda (381) a false alarm (382).

- Chapter 74.—Tribal politics (383) our march (384) desert manners which nearly put an end to us (385) willing help (388).

- Chapter 75.—On the road (389) Turks and English (390) we get two great volunteers (391) more accidents (392) a scratchy night in tents (393) denouncing a fear (394) calmness (395).

- Chapter 76.—Azrak (396) check (397) hiding (399) ready (400).

- Chapter 77.—Apprehension (401) a forced march (403) we attain the bridge at last (404) a panic (405) and a failure (406).

- Chapter 78.—A new idea (407) mine-laying (408) hunger, drizzle and the cold sap our patience (409) a long moment (410).

- Chapter 79.—Distractions, wise and foolish (412) the mine goes off embarrassingly well (413) a rescue (415) we get away (416).

- Chapter 80.—Reconditioning Azrak (417) provisions (418) visitors (419) our leader (420) Azrak nights (421) a digression (422).

- Chapter 81.—A Turkish garrison (423) in detention (424) an argument (425) persuasions (426) which go too far (427) the earned wages of rebellion (428) gentling a broken will (429).

- Chapter 82.—The rake's progress (430) I want to get away (431) in my own despite (432) riding non-stop right to Akaba (433) another break-down (434) I find healing in Jerusalem (435).

BOOK VII.

A WINTER CAMPAIGN.

After the capture of Jerusalem, Allenby, to relieve his right, assigned us a limited objective. We began well; but when we reached the Dead Sea, bad weather, bad temper and division of purpose blunted our offensive spirit and broke up our force. I had a misunderstanding with Zeid, threw in my hand, and returned to Palestine reporting that we had failed, and asking the favour of other employment. Allenby was in the hopeful midst of a great scheme for the spring. He sent me back at once to Feisal with new powers.

- Chapter 83.—Allenby in Jerusalem (437) he puts me to work again (438) an Arab advance (439) Joyce and I joy-ride (440) the British staff do not understand our inconclusiveness (442).

- Chapter 84.—My price and bodyguard (444) the Nahabi (445) our camels (447) severities of service (448) vain nihilism (450).

- Chapter 85.—Extending our front (451) Sherif Nasir's capture of Jurf (452) winter comes down (453) into Tafileh (454).

- Chapter 86.—A Turkish counter attack (456) we run away (457) but later decide to accept battle (458) the battlefield (460).

- Chapter 87.—Our front line gets vexed (461) a lull of sunshine (462) a triple attack (463) the aftermath (464) the profit (465).

- Chapter 88.—Clearing the Dead Sea (466) snow-bound (467) a dash (468) riding under difficulties (469) corrosive cold (470).

- Chapter 89.—Comfort at Guweira (472) a convoy of gold (473) in the open (474) the winter Edomite wind (475) by night (476).

- Chapter 90.—Exhausted (477) my camel (478) the castle (479) child breeding (480) snow-drifts (481) a journey's end (482).

- Chapter 91.—Our next programme (483) a sudden check (484) return to Palestine (485) a complaint and resignation justified by the discovery that my nerves and tact had failed (486).

- Chapter 92.—Again harnessed (487) joint operations impose a new understanding with Feisal and further resources (488).

BOOK VIII.

ORTHODOXY ARRIVES.

In conjunction with Allenby we laid a triple plan to join hands across Jordan, to capture Maan, and to cut off Medina, in one operation. This was too proud and neither of us fulfilled his part. So the Arabs exchanged the care of the placid Medina railway for the greater burden of investing, in Maan, a Turk force as big as their available Regular Army. To help in this duty Allenby increased our transport, that we might have longer range and more mobility. Maan was impregnable for us, so we concentrated on cutting its northern Railway and diverting the Turkish effort to relieve its garrison from the Amman side. Clearly no decision lay in such tactics: but the German advance in Flanders at this moment took from Allenby his British units: and consequently his advantage over the Turks. He notified us that he was unable to attack. A stalemate, as we were, throughout 1918 was an intolerable prospect. We schemed to strengthen the Arab Army for Autumn operations near Deraa and in the Beni Sakhr country. If this drew off one division from the enemy in Palestine it would make possible a British ancillary attack, one of whose ends would be our junction in the lower Jordan valley, by Jericho. After a month's preparation this plan was dropped, because of its risk, and because a better offered.

- Chapter 93.—Staffs (491) sex (492) plans (493) discipline (494).

- Chapter 94.—Away with Mirzuk (496) springtime (497) Allenby falls back (498) amateur spying (499) death of Farraj (500).

- Chapter 95.—The Indians (502) capture of Semna (503) attack on Maan (504) to Dawnay (505) his success (507) Young (509).

- Chapter 96.—An Allenby surprise (510) his reduced strength (511) a gift of camels (512) plans to hold on (513) activity (514).

- Chapter 97.—Nasir in the lead (516) our biggest demolition (517).

- Chapter 98.—Finding reinforcements for an Arab offensive (519) Allenby works against time (520) King Hussein refuses (521).

BOOK IX.

MANŒUVERING FOR A FINAL STROKE.

Allenby, in rapid embodiment of reliefs from Mesopotamia and India, so surpassed hope that he was able to plan an Autumn offensive. The near balance of the forces on each side meant that victory would depend on his subtly deceiving the Turks that their entire danger yet lay beyond the Jordan. We might help, by lying quiet for six weeks, feigning a feebleness which should tempt the Turks to attack. The Arabs were then to lead off at the critical moment by cutting the railway communications of Palestine. Such bluff within bluff called for most accurate timing, since the balance would have been wrecked either by a premature Turkish retreat in Palestine, or by their premature attack against the Arabs beyond Jordan. We borrowed from Allenby some Imperial Camel Corps to lend extra colour to our supposed critical situation; their success glorified them and covered us, while preparations for Deraa went on with no more check than an untimely show of pique from King Hussein.

- Chapter 99.—Allenby's ambitions (523) to fog the Turks (524) Imperial Camel Corps for our sector (525) a raid against Deraa (526) snatch-programme for the I.C.C. (526) supply problems become complicated (527) smoothing the road (528).

- Chapter 100.—Timing the scheme (529) Buxton (529) Nuri Shaalan (531) confirming the Rualla in their faith (532) Feisal preaching (533) the great gulf between him and me (535).

- Chapter 101.—Atonement, redemption, dint of consequence (537).

- Chapter 102.—Buxton's night attack (540) peace negotiations (541) British promises to France, Sherif, Arab and Jew (542).

- Chapter 103.—By car to Azrak (544) troops (547) Buxton (548).

- Chapter 104.—My birthday, by good fortune, is peaceful (549).

- Chapter 105.—A hostile raid (555) the I.C.C. on the road (556) Buxton becomes mobile, and my men camel-drivers (558).

- Chapter 106.—Seen (559) renunciation (560) in the lodge of Amruh (561) Azrak (562) with the armoured cars (563).

- Chapter 107.—King Hussein breaks out again (565) we begin to repair damages (566) stopping little short of forgery (568).

BOOK X.

THE LIBERATION OF DAMASCUS.

Our mobile column of aeroplanes, armoured cars, Arab regulars and Beduin, collected at Azrak to cut the three railways out of Deraa. The southern line we cut near Mafrak; the northern at Arar; the western by Mezerib. We circumnavigated Deraa, and rallied, despite air raids, in the desert. Next day Allenby attacked, and in a few hours had scattered the Turkish armies beyond recovery. I flew to Palestine for aeroplane help, and got orders for a second phase of the thrust northward. We moved behind Deraa to hasten its abandonment. General Barrow joined us; in his company we advanced to Kiswe, and there met the Australian Mounted Corps. The united forces entered Damascus unopposed. Some confusion manifested itself in the city. We strove to allay it; Allenby arrived and smoothed out all difficulties. Afterwards he let me go.

- Chapter 108.—Winterton (571) at Azrak (572) a rest (573) plans (574) reinforcements (575) concentration (576) first step (577).

- Chapter 109.—It starts ill (578) an air fight (579) bombing Deraa (580) a Rolls-Royce operation (581) running repairs (582).

- Chapter 110.—The main line is captured (583) Peake and his tulips (584) aerial interference (585) Junor takes a hand (586).

- Chapter 111.—For the Palestine line (588) Mezerib taken (590) our plunder and a great fire by night attract visitors (591).

- Chapter 112.—A classical project (592) waiting (593) prudence asserts her lovely self (594) doing the round trip (595).

- Chapter 113.—Hejaz line (596) a sunset (597) the last bridge (598).

- Chapter 114.—Visitors (600) shaking us up (601) shaking them up (602) need for air reinforcement (603) a night muddle (604) Allenby in victory (605) the Royal Air Force chiefs (606).

- Chapter 115.—Back to duty (608) resisting importunity (609) an air success (610) the Handley-Page (611) Nuri Shaalan (611).

- Chapter 116.—Another bungle (612) the Turks break (613) a new departure (614) an opposition (615) five different minds (616). Chapter 117.—An army again in all men's eyes (617) three enterprises (618) a pause (619) prisoners in handfuls (620).

- Chapter 118.—The main retreat (621) its sting (622) Auda takes charge (623) blood-thirst (624), the terror by night (625) alone to Deraa (626) Barrow's welcome (627) Feisal (628).

- Chapter 119.—Very near the end (629) war as she should be (630) a good recovery by the British (631) military service (632).

- Chapter 120.—The occupation of Damascus (634) the burning stores (635) at the Town Hall (636) Auda breaks out upon the Druses (637) General Chauvel takes over chief control (638).

- Chapter 121.—Digging in (640) a new administration (641) public order (642) supplies (643) night falls upon us unready (644).

- Chapter 122.—Disorder at dawn (645) peace returns (646) the silent hospital (647) prisoners of war (648) tired out (649).

- Chapter 123.—A quiet morning (650) two standards of perfection (651) of Allenby (651) and of Feisal (652) escape (652).

EPILOGUE

Why the taking of Damascus ended my efforts in Syria (653).

APPENDIX I

Nominal rolls of armoured cars and Talbot battery (654).

APPENDIX II

A diary of place names and dates (656).

t seemed to me that every portrait drawing of a stranger-sitter partook somewhat of the judgement of God. If I could

get the named people of this book drawn, it would be their

appeal to a higher court against my summary descriptions. So I

took pains to bring objects and artists together. ‘Took pains,’ for

my people were in Asia and Africa, besides Europe. I could gather

but few of them, and get to work only some of the artists I respect.

Importunity and the shoals of a shallow purse were my arguments.

If anybody likes any of these illustrations, he owes thanks to

Kennington, who apart from his creative work, took over the duty

of art-editor and for five years oversaw each proof of every block.

Some of the more difficult colour subjects had to be proved repeatedly

(up to seventeen times) and there were twenty three printings on

the worst one. Fortunately I was away in the country, beyond

helping him, for I could not have done the job so well. Kennington,

the printers (both of the text and plates) and I have been partners.

t seemed to me that every portrait drawing of a stranger-sitter partook somewhat of the judgement of God. If I could

get the named people of this book drawn, it would be their

appeal to a higher court against my summary descriptions. So I

took pains to bring objects and artists together. ‘Took pains,’ for

my people were in Asia and Africa, besides Europe. I could gather

but few of them, and get to work only some of the artists I respect.

Importunity and the shoals of a shallow purse were my arguments.

If anybody likes any of these illustrations, he owes thanks to

Kennington, who apart from his creative work, took over the duty

of art-editor and for five years oversaw each proof of every block.

Some of the more difficult colour subjects had to be proved repeatedly

(up to seventeen times) and there were twenty three printings on

the worst one. Fortunately I was away in the country, beyond

helping him, for I could not have done the job so well. Kennington,

the printers (both of the text and plates) and I have been partners.

| The eternal itch | end-paper | wood cut | Kennington |

| Map—western section | fly-leaf | Bartholomew | |

| Feysal | frontispiece | oils | John |

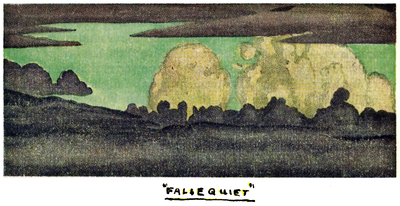

| False quiet | p. xviii | water colour | Kennington |

| Initials A—W | passim | line | Wadsworth |

| The flashing sword | p. 6 | line | Roberts |

| Dignity (p. 43) | p. 23 | line | Roberts |

| Object lesson | p. 29 | line | Roberts |

| Sleeping, Waking (p. 99) | p. 36 | line | Roberts |

| The gad-fly | p. 40 | line | Roberts |

| The creator | p. 47 | wood-cut | Blair H-S |

| Ibrahim Pasha (p. 130) | p. 59 | line | Roberts |

| Spine drill | p. 65 | line | Roberts |

| Victory | p. 75 | line | Roberts |

| A camel ambulance | p. 91 | line | Roberts |

| The prophet’s tomb | p. 92 | line | P. Nash |

| A reluctant shepherd (p. 179) | p. 110 | line | Roberts |

| Suppliants | p. 115 | line | Roberts |

| Male and female (p. 499) | p. 119 | line | Roberts |

| Luxury | p. 161 | line | Roberts |

| The Sirhan (p. 251) | p. 176 | line | Roberts |

| The Dogs of Harith (p. 420) | p. 192 | line | Roberts |

| Ambush | p. 201 | line | Roberts |

| Scouting | p. 207 | line | Roberts |

| A garden | p. 208 | line | P. Nash |

| Khamsin | p. 229 | line | Roberts |

| Mucking in | p. 280 | line | Roberts |

| A forced landing | p. 284 | line | Kennington |

| Camel march | p. 294 | pen & wash | Roberts |

| Wind | p. 301 | line | Kennington |

| Off duty | p. 308 | line | Roberts |

| Why not run away? | p. 321 | wood-cut | Blair H-S |

| The last prophet | p. 339 | wood-cut | Blair H-S |

| Appeasing a tumult | p. 347 | line | Roberts |

| At a well | p. 364 | charcoal | J.C. Clark |

| The little less | p. 372 | line | Roberts |

| The Oxford manner | p. 395 | line | Roberts |

| Standards of value | p. 400 | wood-cut | Blair H-S |

| A miscarriage | p. 411 | line | Kennington |

| A jolly evening | p. 416 | line | Roberts |

| Kindergarten | p. 443 | line | Kennington |

| As-hab | p. 460 | line | Roberts |

| Staff conference | p. 465 | line | Roberts |

| Temptation of necessary food | p. 476 | line | Kennington |

| Us all | p. 482 | line | Kennington |

| Body, spirit, soul | p. 489 | wood-cut | Blair H-S |

| Irish troops being shelled | p. 490 | oils | Lamb |

| Dhaif Allah (p. 212) | p. 509 | line | Kennington |

| Beyond the end | p. 515 | wood-cut | Blair H-S |

| Good intentions | p. 521 | line | Kennington |

| A literary method | p. 522 | line | Kennington |

| Mudowwara | p. 522 | air photograph | R.F.C. |

| In his own image | p. 536 | wood-cut | Blair H-S |

| The sport of kings | p. 539 | wood-cut | Blair H-S |

| Introspection | p. 554 | line | Kennington |

| The body survives the soul | p. 558 | wood-cut | Blair H-S |

| The glory of a young man | p. 564 | wood-cut | Kennington |

| Conscience our guide | p. 569 | wood-cut | Blair H-S |

| As-hab | p. 591 | line | Roberts |

| Infantry | p. 595 | wood-cut | Kennington |

| High explosive | p. 599 | wood-cut | G. Hermes |

| A Garden | p. 607 | line | P. Nash |

| Dhat el Haj | p. 616 | pen & wash | P. Nash |

| The goal | p. 639 | line | Roberts |

| The prophet's tomb | p. 644 | line | P. Nash |

| Cæsar | p. 649 | line | Kennington |

| A rabbit | p. 652 | wood-cut | Kennington |

| Maps | p. 661 | Bartholomew |

Illustrations following the text

| Jidda—five street-scenes | photographs | ||

| Allenby | pastel | Kennington | |

| Wilson | pastel | Kennington | |

| Boyle | pastel | Kennington | |

| Storrs | pastel | Kennington | |

| Author | pastel | Kennington | |

| Blasted tree | chalk | Kennington | |

| Lloyd | oils | Roberts | |

| Night bombing | line | Roberts | |

| Emir Abdulla | pastel | Kennington | |

| Jaafar | pastel | Kennington | |

| Shakir | pastel | Kennington | |

| Auda abu Tayi | pastel | Kennington | |

| Ali ibn el Hussein | pastel | Kennington | |

| Nawaf Shaalan | pastel | Kennington | |

| Ghalib | pastel | Kennington | |

| Matar | pastel | Kennington | |

| Mukheymer | pastel | Kennington | |

| Saad el Sikeini | pastel | Kennington | |

| Mohammed el Sheheri | pastel | Kennington | |

| Mahmas | pastel | Kennington | |

| el Zaagi | pastel | Kennington | |

| Serj | pastel | Kennington | |

| Alayan | pastel | Kennington | |

| Hemeid Abu Jabir | pastel | Kennington | |

| Tafas | pastel | Kennington | |

| Hussein Mohammed | pastel | Kennington | |

| Abd el Rahman | pastel | Kennington | |

| At Akaba | chalk | J.C. Clark | |

| Hogarth | charcoal | John | |

| Storrs | charcoal | Sargent | |

| Joyce | pencil | Dobson | |

| Young | chalk | R.M. Young | |

| Bartholomew | chalk | Colin Gill | |

| G. Dawnay | pencil | Lamb | |

| Junor | pencil | G. Spencer | |

| Newcombe | pencil | Roberts | |

| Buxton | pencil | Roberts | |

| Wingate | chalk | Roberts | |

| McMahon | pencil | Roberts | |

| Winterton | pencil | Roberts | |

| A. Dawnay | chalk | Rothenstein | |

| Clayton | pen & wash | W. Nicholson | |

| Author | pencil | John | |

| Waterfall | pen & wash | Paul Nash | |

| El Sakhara | pencil | Slatter | |

| Mountains | pen & wash | Paul Nash | |

| Dysentery | water colour | Kennington | |

| Stokes' gun class | oil | J.C. Clark | |

| Nightmare | water colour | Kennington | |

| Strata | pencil | Kennington | |

| Thinking | water colour | Kennington | |

| In a tent | chalk | Kennington | |

| Bombing in Wadi Fara | oils | Carline | |

| Tafas | water colour | Kennington | |

| Entering Damascus | photograph | ||

| The world, the flesh, the devil | end-paper | wood-cut | Kennington |

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published in 1922, before the cutoff of January 1, 1929.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1983, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 40 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse