Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections/Volume 60/Remains in Eastern Asia of the Race that Peopled America

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS

VOLUME 60, NUMBER 16

REMAINS IN EASTERN ASIA OF THE

RACE THAT PEOPLED AMERICA

(With Three Plates)

BY

Dr. A. HRDLIČKA

Curator of the Division of Physical Anthropology, U. S. National Museum

(Publication 2159)

CITY OF WASHINGTON

PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

DECEMBER 31, 1912

BALTIMORE, MD., U. S. A.

REMAINS IN EASTERN ASIA OF THE RACE THAT PEOPLED AMERICA

(With Three Plates)

By DR. A. HRDLIČKA

curator of the division of physical anthropology, U. S. National Museum

During the summer of 1912 the writer visited, partly under the auspices of the Smithsonian Institution and partly in the interest of the Panama-Californian Exposition of San Diego, certain portions of Siberia and Mongolia in search for possible remains of the race that peopled America, and whose home, according to all indications, was in eastern Asia. Upon the return of the writer from his journey in September this brief report was presented at the International Congress of Prehistoric Anthropology and Archeology at Geneva.

The journey extended to certain regions in southern Siberia, both west and east of Lake Baikal, and to Mongolia as far as Urga. It furnished an opportunity for a rapid survey, from the anthropological standpoint, of the field and conditions in those regions, and was made in connection with a prolonged research into the problems of the ethnic nature and origin of the American aborigines carried on by the writer on this continent.

The studies of American anthropologists and archeologists have for a long time been strengthening our opinion that the American native did not originate in America, but is the result of a comparatively recent, post-glacial, immigration into this country; that he is physically and otherwise most closely related to the yellow-brown peoples of eastern Asia and Polynesia; and that in all probability he represents, in the main at least, a gradual overflow from north-eastern Siberia.[1] If our views concerning the origin of the Indian and his comparatively late coming into America be correct, then it seems there ought to exist to this day, in some parts of eastern Asia, archeological remains, and possibly even survivals, of the physical stock from which our aborigines resulted. For it could have been no small people that sent us in the course of several thousand years the various more pronounced sub-types of the American Indian, which according to all indications have developed outside of America. As a matter of fact, we have searched and watched for evidence concerning such remains for many years, and every publication that dealt with archeological exploration in eastern Asia or brought photographs of the natives, has in one way or another strengthened our expectations.

No archeologic work on an adequate scale, however, and no comprehensive anthropologic investigation of the natives of eastern Asia, have as yet been carried out, and in consequence many points on which light was needed remained uncertain.[2] Under these circumstances the writer was very desirous to visit personally at least a few of the more important parts of eastern Asia, to observe what was to be found there, and to determine what should be done in those regions by anthropologists and archeologists interested in the problem of the identity and origin of the American Indian.

An opportunity to undertake something in this direction came at last during the present year; but the means were limited and necessitated a restriction of the trip to the more important and at the same time more accessible territory. The choice was made of certain parts of south-eastern Siberia and of northern Mongolia, including Urga, the capital of outer Mongolia, which encloses two great monasteries and is constantly visited by a large number of the natives from all parts of the country. Besides the field observations a visit was also made to the various Siberian museums within the area covered, for the purpose of seeing their anthropological collections.

It will not be possible to enter here into details of the journey and I shall, therefore, restrict myself to mentioning in brief the main results. Thanks to the Russian men of science and the Russian political as well as military authorities, my journey was everywhere facilitated, I was spared delays, was shown freely the existing collections, and received much valuable information.

I have seen, or been told, of thousands upon thousands of as yet barely touched burial mounds or “kourgans”, dating from the present time back to the period when nothing but stone implements were used by man in those regions. These kourgans dot the country about the Yenisei and its affluents, about the Selenga and its tributaries, along the rivers in northern Mongolia, particularly the Kerulen, and in many other parts regarding which reliable information could be obtained. The little investigation that has been made of these remains is due, in the main, to Adrianov and his colleagues at Minusinsk, and especially to Professor Talko-Hryncewitz of Krakow, who was for many years the government physician at Kiachta. The mounds yield, according to their age, implements of iron, copper, bronze, or stone, occasionally some gold ornaments, and skeletons. The majority of these “kourgans” date doubtless from fairly recent times, corresponding to Ugrian or Turk or “Tatar[3]” elements, and to the modern Mongolian, and the skeletons found in them show mostly brachycephalic skulls, which occasionally resemble quite closely American crania of the same form. The older kourgans, on the other hand, particularly those in which no metal occurs, yield an increasing number of dolichocephalic crania, in which close resemblances with the dolichocephalic skulls of the American Indians are very frequent. To what people these older remains belong is as yet an unanswered question; but there are in certain localities, as for instance on the lower Yenisei, to this day remnants of native populations among whom dolichocephalic individuals are quite common, and these individuals often bear a most remarkable physical resemblance to the American Indian.

Besides mounds, the writer saw and learned of numerous large caverns, particularly in the mountains bordering the Yenisei River, which offer excellent opportunities for archeological investigation. Very little research work has thus far been done in these caverns, but some have yielded, to Jelieniev, stone implements that indicate old burials.

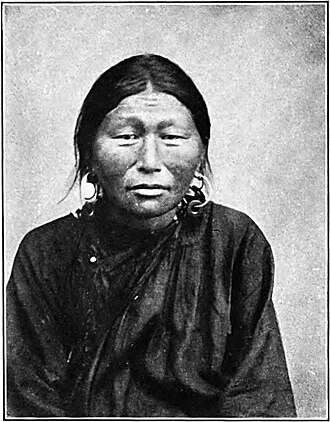

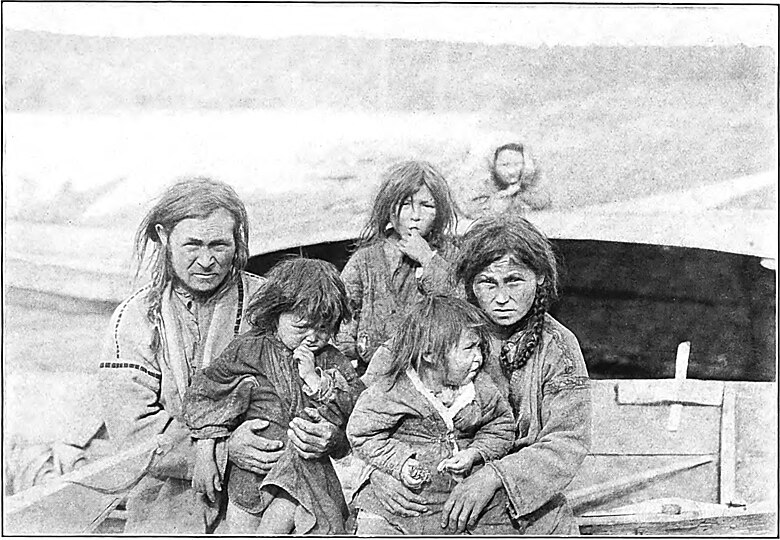

In regard to the living people, the writer had the opportunity of seeing numerous Buriats, representatives of a number of tribes on the Yenisei and Abacan Rivers, many thousands of Mongolians, a number of Tibetans, and many Chinese with a few Manchurians. On one occasion alone, that of an important religious ceremony, he had an opportunity to observe over 7,000 natives assembled from all parts of Mongolia. He has also seen photographs of members of some of the eastern Siberian tribes. Among all these people, but more especially among the Yenisei Ostiaks, the Abacan Katchinci and related groups, the Selenga Buriats, the eastern Mongolians, the Tibetans, the east Siberian Oroczi and the Sachalin Giliaks, there are visible many and unmistakable traces of admixture or persistence of what appears to have been the older population of these regions, pre-Mongolian and especially pre-Chinese,[4] as we know these nations at the present day. Those representing these vestiges belong partly to the brachycephalic and in a smaller extent to the dolichocephalic type, and resemble to the point of identity American Indians of corresponding head form. These men, women and children are brown in color, have black straight hair, dark brown eyes, and facial as well as bodily features which remind one most forcibly of the native Americans. Many of these individuals, especially the women and children, who are individually less modified by the environment than the men, if introduced among the Indians and dressed to correspond, could by no means at the disposal of the anthropologist be distinguished apart. And the similarities extend to the mental make up of the people, as well as to numerous habits and customs which new contacts and religions have not as yet been able to efface.

The writer found much more in this direction than he had hoped for, and the physical resemblances between these numerous outcroppings of the older blood and types of north-eastern Asia and the American Indian, cannot be regarded as accidental, for they are numerous as well as important and cannot be found in parts of the world not peopled by the yellow-brown race; nor can they be taken as an indication of American migration to Asia, for emigration of man follows the laws of least resistance, or greatest advantage, and these conditions surely lay more in the direction from Asia to America than the reverse.

In conclusion, it may be said that from what he learned in eastern Asia, and weighing the evidence with due respect to other possible views, the writer feels justified in advancing the opinion that there exist to-day over large parts of eastern Siberia, and in Mongolia, Tibet, and other regions in that part of the world, numerous remains, which now form constituent parts of more modern tribes or nations, of a more ancient population (related in origin perhaps with the latest paleolithic European), which was physically identical with and in all probability gave rise to the American Indian.

The writer is able to merely touch on the great subject thus approached. The task of learning the exact truth remains for the future. In relation to opportunities for further investigation, he has satisfied himself that the field for anthropological and archeological research in eastern Asia is vast, rich, to a large extent still virginal, and probably not excessively complicated. It is surely a field which calls for close attention not only on the part of European students of the Far East, but especially on the part of the American investigator who deals with the problems of the origin and immigration of the American Indian.

- ↑ For a summary of these opinions see “The Problems of the Unity or Plurality and the Probable Place of Origin of the American Aborigines” in The American Anthropologist, Vol. 14, No. 1, January-March, 1912.

- ↑ It is only fair, however, that attention be called here to the Bogoraz and Jochelson work among the natives of Northern Siberia, as a part of the Jessup Expedition, for the American Museum of Natural History, New York City. Regrettably this work did not extend far enough to the south.

- ↑ The term “Tatar” in Siberia is applied to large numbers of natives and covers a number of physically heterogeneous types.

- ↑ The Mongolians of to-day are a mosaic or mixture of various local, southern and particularly western ethnic elements; while the Chinese present in the main a people that has undergone to a very perceptible degree its own differentiation, so as to constitute a veritable great subtype of the yellow-brown people.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1929.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1943, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 80 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse