The Achehnese/Volume 2/Chapter 1

CHAPTER I.

LEARNING AND SCIENCE.

§ 1. The practice of the three branches of Mohammedan teaching and its preliminary study in Acheh.

The learning of Islam.In Acheh, as in all countries where Islam prevails, there is, properly speaking, but one kind of science or learning (Ach. èleumèë, from the Arabic ʿilmu), embracing all that man must believe and perform in accordance with the will of Allah as revealed to his latest Apostle Mohammad. It has in view the high and eminently practical purpose of enabling man to live so as tg please God, and opening for him the door of eternal salvation. Beside it, all other human science is regarded as of a lower order, and serving merely to the attainment of worldly ends, both those which are permitted and those which are forbidden by the sacred Law.

In Mohammad's time and for a little while after, this single branch of knowledge was very simple and of small compass. The historical development of Islam, however, very soon produced dissent and brought new doctrines into being, so that the encyclopaedia of Mohammedan lore attained very respectable proportions, and the teachers were compelled in spite of themselves to concentrate their powers on single subjects.

To gain some insight into the encylopaedia of Mohammedan learning we must examine the chief features of the history of its composition. These I have already sketched in the introduction to my description of learned life in the Mecca of to-day[1], so it need not be repeated here. It is enough to recapitulate those branches of Mohammedan learning which are to some extent practised in Acheh.

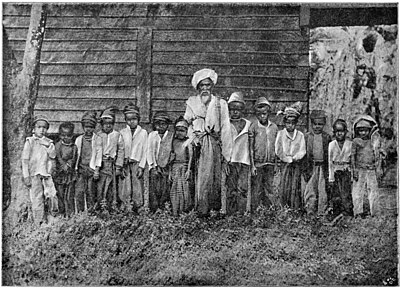

A TEACHER OF KURUʾAN-RECITAL WITH HIS PUPILS.

Results of the Qurān-instruction.What the pupil attains in his Qurān curriculum, is the capacity to recite correctly the portions of the holy writ required for his daily prayers. He is also able eventually to chant upon occasion extracts from the sacred Book according to the strict rules of the art, by way of a voluntary act of devotion. Besides this, the non-Arab learner gains an intimate acquaintance with a strange and difficult system of sounds, and thus acquires in passing some knowledge of phonetic science.

Those who pass through the Qurān-school are able, so far as they do not speedily forget what they have learned, to read the Arabic character with the vowel sounds; but unless they extend their studies further, this does not enable them to read Malay, or even Achehnese written in Arabic character.

There are thus even among the higher classes very many persons who know little or nothing of reading; and the art of writing is still less widely disseminated. I have often heard Achehnese declare that they found it much more of a burden than a pleasure to be able to write. Personally they may seldom require to exercise their skill in writing; but every one who wants a letter or other document written betakes himself as a matter of course to his expert fellow-villager, and even seems to think he has a claim on the latter’s good-nature for the supply of the requisite stationery.

We have already noticed the part played by this elementary instruction in the education of the Achehnese[2]. The organs of speech of the latter, like those of the Javanese, experience great difficulty in reproducing Arabic sounds. Thus all the purely Achehnese teachers who have not been grounded in the art of recitation under the strict instruction of a foreigner, diverge to a vast extent from the Arabic gamut of sounds. Their nasal pronunciation of the ʿain they have in common with other Indonesians, but the pronunciation, for example, of an accented u or an as èë[3] is peculiarly Achehnese. Here, as in Java, these national peculiarities have of later years begun to disappear, since many of the best teachers are now schooled in Mekka. The lesser pandits learn of these or of professional Egyptian Qurān reciters, who occasionally make a tour through Acheh.

Course of instruction to the Qurān.When the pupil has practised the Arabic character with the aid of a wooden tablet (lòh), he is given the last of the 30 portions (Ach. juïh) of the Qurān, written or printed separately, and recites this under the guidance of the teacher (ureuëng pumubeuët or gurèë). This portion is called juïh ama ((Arabic characters)) from its initial word, and that which precedes it juïh taba from the first two syllables of its initial word ((Arabic characters)). In the curriculum the juïh taba comes after the juïh ama, and it is not till he has spelled out (hija) and chanted both of these to the satisfaction of his teacher, that the pupil begins the recitation of the whole Qurān from the fātiḥah, the Mohammedan Lord's Prayer[4], to the end of the 114th Surah.

Other elementary instruction.Those who are content with a minimum of further study, that is to say almost all girls and most boys, next proceed to learn the absolute essentials of religious lore from a small catechism, which we shall met with later on, in Achehnese prose and verse, in our description of their literature (nos XCI to XCVII). They are also exercised either by word of mouth or with manuscript to guide them, under the supervision of parents or schoolmasters, in the performance of the five daily ritual prayers (Ach. seumayang) prescribed for all Mohammedans.

The majority acquire this indispensable knowledge simply by imitation of what they see and hear others do. Those who employ documentary aid are not as a rule content with the Achehnese works. They read under proper guidance Malay text-books such as those named Masaïlah and Bidayah, which treat in a simple manner of the absolute first principles of religious doctrine and of the religious obligations of the Moslim. The teacher (male or female) must however explain it all in Achehnese, since a knowledge of Malay is comparatively rare in Acheh. A work such as the rhyming guide to Malay (see n°. XCVIII of the Achehnese works enumerated in the next chapter) serves simply to make it easy to remember the words most required.

Indispendability of a knowledge of the Malay language for more advanced study in Acheh.The part played by Malay in Acheh in the acquisition of religious learning is almost the same as that assumed by Javanese in the Sunda country. An Achehnese who desires to learn something beyond the first elements of doctrine and law finds Malay indispensable. Even the few popular manuals in his own tongue bristle with Malay words, while reliable renderings of authoritative Arabic works, which are fairly numerous in Malay, are entirely wanting in Achehnese.

Thus those who, without actually devoting themselves to study, still take pleasure in increasing their religious knowledge so far as time and circumstances allow, learn Malay en passant as they read. This they must do in order to be able to understand even the simplest "kitab." A Malay kitab is a work derived or compiled from Arabic sources; as a rule only the introduction, the conclusion, and a few passing remarks are the work of the "author", the rest being mere translation.

There is a superabundance of Malay kitabs of this description. One, the Çirāt al-mustaqīm, written in Acheh by a non-Achehnese pandit of Arab origin from Gujerat, just about the period of Achch's greatest prosperity, before the middle of the 17th century, is still much in vogue, though later Malay works on the law of Islam have now begun to supersede it.

Not a few Achehnese, whose position demands that they should devote themselves to study, rest content with the perfunctory perusal of some such Malay kitabs, as these suffice to enable them to officiate, say as teungku meunasah[5] or even as kali[6]. But though such may be called leubè or malém[7], or even além in times and places where there is a scarcity of religious teachers, they are never known as ulama, for this name is reserved for the doctor who can enlighten others on matters connected with the law and religious doctrine with some show of authority.

What is required of an ulama.To be able to lay claim to the title of doctor it is necessary at least to have studied, under competent guidance, some few authoritative Arabic works on law and doctrine. To reach this end the Achehnese employ a method different from that which has since ancient times been followed by the Javanese and Sundanese,—a method which certainly appears more rational, but which is on the other hand so fraught with difficulties, that most of those who adopt it lose courage long before they attain their purpose.

Difference between the methods of instruction in vogue in Java and in Acheh.Thus in Java the preparatory subjects (Arabic grammar etc.) so indispensable in theory are left in abeyance and often not practised till the very end. The pupil after being grounded in a few elementary manuals is immediately introduced to the greater Arabic text-books.

These he reads sentence by sentence under the guidance of a teacher who probably knows as little of Arabic grammar as his pupil, so that if he makes no serious mistakes in vocalizing the Arabic consonants, he owes it to his good memory alone. After each sentence is read, the teacher translates it into Javanese; the language employed of course differs greatly from that of daily life, as it is a literal rendering of the Arabic text, dealing with learned subjects and leaving technical terms untranslated as a rule. It is only the similarity of these subjects one with another and the unvarying style of the writers that assist the pupil in committing to memory the text (lapal)[8] and translations (maʾna or logat)[8]. The teacher follows up his word-for-word translation with an explanatory paraphrase (murad)[8], designed to make the author's meaning comprehensible.

Strange as it may appear, diligent students attain in the end so much proficiency by this curious method, as to be able to translate from Arabic into Javanese simple text-books. They are of course liable to gross errors, and even their vocalizing of the Arabic words is seldom entirely accurate. Much depends on the comparative age of their traditions in affairs of grammar. Where for instance their teacher or their teacher's teacher was well grounded in grammar, they are likely to pass on the text in a more uncorrupted form than if it had been for a long time past transmitted from the memory of one to that of his successor.

The chief reason why the patience of the Javanese students does not become exhausted in this process, is that they feel the sum of their knowledge augmented by each lesson. They take a pleasure in the consciousness of having read the authoritative text (lapal) in the original and this they would miss did they like the great majority limit themselves to the reading of Javanese works. The subsequent literal translation (logat or maʾna) removes all doubt as to the meaning of the Arabic words, and the explanation (murad) makes the matter digestible and capable of being applied.

Gradual modification of the method in Java.The other method of instruction which has during the last thirty or forty years gradually gained supremacy in Java under Mekkan and Ḥadramite influence, is more logical, but requires much greater patience and perseverance. It takes several years for the Indonesian to learn enough Arabic to enable him to begin to read a simple learned work with some degree of discrimination. This preparation costs him no little racking of his brains, the results of which he cannot hope to enjoy for a long time to come.

The Sundanese follow the same system as the Javanese, but with this additional difficulty, that the language into which the translation is made (Javanese) is strange to them, and that only the exposition (murad) is given them in their own tongue.

This method, which in Java may still be called new-fashioned, appears to have been in vogue in Acheh for a long time past. It is only those who do not really devote themselves to study who employ the elementary Malay books, just as the Sundanese under similar circumstances avail themselves of Javanese works, or even of those written in their own tongue. But the student in Acheh begins by struggling through a mountain of grammatical matter.

THe study of Arabic grammar in Acheh.First comes the science of inflexions, sarah or teuseuréh (Arab. çarf or taçrīf), for which are employed manuals consisting chiefly of paradigms, especially that known as Midan (Arab. Mīzān). These are followed by a number of widely known works on Arabic grammar (nahu), which are generally studied in the order given below. The Achehnese names are as follows, the Arabic equivalents being given in the note[9]: Awamè, Jeurumiah, Matamimah, Pawakèh, Alpiah, Ebeunu Aké.

Difficulties of the Achehnese method.It must be borne in mind that the Achehnese have the same difficulty to overcome as the Sundanese, since for them too the text-books are translated into a foreign language, the Malay. Thus we can easily understand how the majority of students in Acheh fail to complete what we might call the preliminary studies (known to the Arabs as ālāt or "instruments"), by the correct handling of which one may master the principal branches of religious learning.

The popular verdict on the numerous scholars who have got no further than the Alpiah, yet are wont to vaunt themselves on their learning, finds expression in the verse which passes as a proverb among the Achehnese: "Study of grammar leads only to bragging, study of the Law produces saints"[10], On the other hand a certain reverence lurks in the idea that prevails among the ignorant, that he who has studied the nahu is able to comprehend the tongues of beasts.

Besides the grammatical lore, there are also other "instruments", branches of learning subsidiary to the study of the law and of religious doctrine, but in no Mohammedan country and least of all in Acheh is the acquirement of these considered an indispensable prelude to the more advanced subjects. Such are for example the various subdivisions of style and rhetoric, arithmetical science (indispensable in the study of the law of inheritance), astronomy, which assists in determining the calendar and the qiblah, and so forth. These subjects are indeed taught in Acheh, but they occupy no certain place in the curriculum generally adopted; the time spent on them depends very much on the pleasure of the students and the extent of their teacher'’ knowledge.

Main object of study.The main purpose of study should be, properly speaking, the knowledge of Allah's law as revealed through Mohammed in the Qurān and in his own example (Sunnah), and as in the lapse of time (with the help of Qiyās or reasoning by analogy) confirmed and certified by the general consent (Ijmāʿ) of the Moslim community. With the students or teachers of to-day, however, the knowledge of this law cannot be acquired by the study of the Qurān and its commentaries together with the sacred tradition as to the acts (sunnah) of the Prophet. For such direct derivation of religious rules from their original sources a degree of knowledge is required which is at present regarded as quite beyond the student's reach. He has to restrict himself to the authoritative works in which the materials are moulded and arranged according to their subjects. In these studies each is bound to follow the law- books of the school (maḍhab) to which he belongs, although he must also recognize the full rights of the three other schools to their own: interpretation of the law.

Authoritative law-books.Applying this principle to Acheh, we arrive at the conclusion—a conclusion fully justified by the facts—that the chief objects of study in that country are the authoritative Shafiʾite works on the learning of the law (Arab. fiqh, Ach. pikah). As these books are the same in all Shafiʾite countries, and the choice of any particular one of them does not affect the subject-matter of study, I consider it superfluous to give a list of this pikah-literature. I confine myself to observing that Nawawi's Minhāj aṭṭālibīn (Ach. Mènhòt) and various commentaries thereon such as the Fatḥ al-Wahhāḅ (Ach. Peuthōwahab), the Tuḥfah[11] (Ach. Tupah) and Maḥalli (Mahali) enjoy great popularity.

Study of dogma.The Usuy (Uçūl or Tawḥīd), i. e. "doctrine", is next in importance to the Pikah. Both branches of learning are studied simultaneously; the former may even precede the latter if circumstances so require. The differences of the four schools or maḍhabs exercise no influence on this score, as they do in regard to the interpretation of the law. Thus even in a Shafiʾite country preference is by no means always given to such Usul-works as have Shafiʾites for their authors.

In Acheh the same works are employed for this branch of study as in other parts of the Archipelago, and especially those of Sanusi with their accompanying commentaries.

Mysticism.The great Moslim father al-Ghazali (ob. 1111 A. D.) describes the study of the law (Ach. Pikah) as the indispensable bread of life of the believers, the dogmatic teaching (Usuy) being the medicine which mankind, threatened with all manner of heresy and unbelief, is constrained to use as preventive and as cure. Lastly he considers mysticism (Arab. taçawwuf, Ach. teusawōh) the highest and most important element in man's spiritual education, since it serves so to digest the bread of life and the medicine, that a true knowledge of God and of the community of mankind with the Creator may spring therefrom.

Many works on the law and on dogma contain here and there mystic points of view, but expressly mystic orthodox works are also studied in Acheh.

The more popular kind of mysticism.Yet these works on mysticism cannot be said to be popular in Acheh. As we know, a sort of heretical mysticism found its way into the E. Indian Archipelago simultaneously with the introduction of Islam, and still continues to exercise a great supremacy over men's minds, in spite of influences originating directly or indirectly from Arabia. There can be no doubt—numbers of written documents testify to it—that this mysticism was brought hither by the pioneers of Islam from Hindustan. The most important works on mysticism in vogue in the Archipelago were penned by Indian writers, or else are derived from a body of mystics which flourished in Medina in the 17th century and which was strongly subject to Indian influence. To this body belonged Aḥmad Qushāshī,[12] whose disciples became the teachers of the devout in Javanese and Malayan Countries.

Many of these Indian authors and also Qushāshī and his disciples, represent a mysticism which though regarded by cautious and sober doctors of the law as not exempt from danger, is still free from actual heresy. Behind this orthodox mysticism comes another, hardly distinguishable from the first on a superficial view, but which by its unequivocal pantheism and its contempt for sundry ritual and traditional elements of Islam, has incurred the hatred of all orthodox Mohammedans.

§ 2. The Heretical Mysticism and its Antagonists.

Heretical mysticism.The heretical mysticism, of which there are numerous distinct shades, fell here, as in India, on fruitful soil, and nothing but the persecutions which orthodox theologians occasionally succeeded in inducing the princes to resort to, were able to thrust this pantheistic heresy back to narrow limits.

This latter sort of mysticism has this in common with the orthodox kind, that it finds in man’s community with his Maker the essence and object of religion, and regards ritual, law and doctrine merely as the means to that end. Many of the representatives of this mysticism almost at once forsook the orthodox track and embraced the belief that other means than those mentioned above also lead to the desired end, and that those who live in community with God are already here on earth raised to some extent above ritual and law; the religious teaching of these is entirely different from the official sort, and is at most connected with the latter by arbitrary interpretations and by allegory. Most of them also so conceive the community with God, that the distinction between the creature and the Creator is lost sight of.

This pantheism is set forth by some authors in the form of a philosophy; others—and these are the most popular—describe it in mysterious formulas and in sundry comparisons, based on a play on words or numbers. They illustrate, for example, the doctrine that every part of creation is a manifestation of the Creator's being, by pointing to the higher unity in which move harmoniously the four winds, the four elements, the four chief components of ritual prayer, the four archangels, the four righteous successors of Mohammed and the four orthodox schools of jurisprudence. Now as with man the four limbs correspond with the four great inspired books and the four sorts of qualities of God, so we see how among other things this ever-recurring number four demonstrates the unity of the whole of God's creation, It is the task of mysticism to awaken in man the consciousness of this unity, so that he may identify himself alike with God and with the Universal.

The almost universal influence formerly enjoyed by this sort of mysticism is shown by the vast number of manuscripts to be found among the Indonesian Mohammedans, proclaiming this teaching with the aid of pantheistic explanations of orthodox formulas, allegorical figures with marginal notes, arguments etc. To this it may be added that while varying greatly in detail, they are entirely at one in their main purpose.

Spread of pantheistic mysticism throughout the Archipelago.This scheme of universal philosophy was (and is still, though in a diminishing degree) represented by those occupied in the study and teaching of the law,[13] just as much as by the village philosophers and the spiritual advisers of the chiefs. Now it is obvious that these religious teachers have never gone so far as to assume from the mystic unity of Creature and Creator the nullity or superfluity of the Law. In their opinion the fulfilment of this law was indispensable, although in practice fruitless for the majority of those who are in name believers, since they have not grasped the deep mystic significance of the ritual observances and of the law in general.

Others however go much further and assert that this complete consciousness of the universal unity is a universal sěmbahyang or prayer, which does away with the necessity for the five daily devotional exercises of ordinary men. Nay they sometimes go so far as to brand as a servant of many gods one who continues to offer up his sěmbahyang or to testify that there is no God but Allah, since he that truly comprehends the Unity knows that "there is no receiver of prayer and no offerer thereof;" for the One cannot pray to or worship itself. The Javanese put such philosophy in the mouths of their greatest saints, and among the Malays and Achehnese also, teachers who proclaimed such views have been universally revered since early times.

Mysticism in Acheh in the 16th and 17th centuries.From the chronicles of Acheh, portions of which have been published by Dr. Niemann,[14] we learn somewhat of the religio-philosophical life in Acheh in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. We see there that the religious pandits who held mastery in the country were not Achchnese, but either Syrians or Egyptians who came to Acheh from Mekka, or else natives of India, such as Ranīrī[15] from Gujerat. We also notice that what the Achehnese of that day specially desired of their foreign teachers was enlightenment on questions of mysticism, as to which much contention prevailed.

Shamsuddīn and Hamza Pansuri.The best known representatives of a more or less pantheistic mysticism were a certain Shaikh Shamsuddīn of Sumatra (= Pasè), who seems to have enjoyed much consideration at the court of the great Meukuta Alam (1607–36)[16], and who died in 1630, and his forerunner Hamzah Pansuri.[17]

Persecution of heretics.The orthodox opponents of this Indo-Mohammedan theosophy in a Malay dress won their wish under the successor of Meukuta Alam, who at their instigation put the disciples of Hamzah to death, and had the books which embodied his teaching burnt. Many of these works, however, escaped the flames,[18] and the princes and chiefs of Acheh were not always so obedient to the orthodox persecutors. Even to the present day Hamzah's writings are to be met with both in Acheh and in Malay countries, and in spite of the disapproval of the pandits they form the spiritual food of many.

In the language of the Arab mysticism, he who strives after communion with God is a sālik or walker on the way (ṭarīqah) leading to the highest. Although these words are also used by most of the orthodox mystics, popular expression in Acheh has specially applied the term sālik-learning (èleumèë saléʾ) to such mystic systems as are held in abhorrence by the orthodox teachers of the law.

About 30 or 40 years ago one Teungku Teureubuë[19] acquired a great celebrity in the Pidië district as a teacher of such èleumèë saléʾ. Men and women crowded in hundreds to listen to his teaching. Even his opponents gave him the credit of having been extremely well versed in Arabic grammar, a thing we rarely hear of other native mystics. Yet the opposition which his peculiar doctrines excited among the representatives of the official orthodoxy was so great that they instigated Béntara Keumangan (chief of the league of the six ulèëbalangs) to extirpate the heretics. The teacher and many of his faithful disciples set a seal to their belief by their death. [Notwithstanding this, T. Teureubuë found a successor in his disciple Teungku Gadè, also known as Teungku di Geudōng or (from the name of the gampōng where he lives) Teungku Teupin Raya. In the centre of this gampōng is the tomb of Teungku Teureubuë, surrounded by a thick and lofty wall. The village is under the control of the teacher and is mainly peopled with his disciples.]

Habib Seunagan.No such violent end overtook the Habib[20] Seunagan, who died some years ago. He derived his name from the scene of his labours on the West Coast to the South of Meulabōh. Before he had attained celebrity he was known as Teungku Peunadòʾ, after the gampōng in Pidië where he was born.

The teaching of this heretical mystic is known to me only from information furnished by his opponents, and therefore necessarily very one-sided. He is said to have disseminated the teaching of Hamzah Pansuri, but the statements made regarding his interpretation of the Qurān and the Jaw show it to have been in no special degree mystical, although greatly at variance with the official teaching. He is reported for instance to have held that one might handle the Quran even when in a state of ritual impurity, and that a man might have nine wives at once, opinions anciently upheld by the Ẓāhirites.[21] He is also supposed to have had his own special conception of the qiblah (the direction in which the worshipper must turn his face in the daily ritual prayers), and a dissenting confession of faith, viz. "There is no God but Allah, this Habib is truly the body of the Prophet."[22]

Pidië and some portions of the West Coast, such as Susōh and Meulabōh, are still regarded as districts where the èleumèë saléʾ flourishes. [In Seunagan one Teungku di Kruëng (ob. 1902) may be considered as the spiritual successor of Habib Seunagan.]

Teungku di Kuala.After this digression we must now turn back for a moment to an earlier period, not with the view of giving a complete history of Achehnese theology, but to recall attention to a remarkable Malay, whom

TEUKU BÉNTARA GEUMPANG PAYŌNG.

TEUKOE MEUNTRÒË GARŌT (OF THE FEDERATION OF THE "SIX ULÈËBALANGS").

PÒCHUT DI RAMBŌNG, WIDOW OF A FORMER BÉNTARA KEUMANGAN (TITLE OF THE CHIEF OF THE FEDERATION OF THE SIX "ULÈËBALANGS").

CHUT MANJAʾ, DAUGHTER OF THE PRESENT BÉNTARA KEUMANGAN.

In Van den Berg's Catalogue[24] of the Malay MSS. at Batavia collected by the late H. Von de Wall we find mentioned (p. 8 n° 41):—

(Arabic characters) "A work on the confession of faith, prayer, and the unity ((Arabic characters)) of Allah."

These words very imperfectly indicate the contents of this Umdat al-muhtājīn, of which I have also found a copy in Leiden[25] and another in the Royal Library at Berlin,[26] and have acquired a third by purchase.[27] The book consists of 7 chapters (called faidahs), the chief aim of which is the description of a certain special kind of mysticism, of which ḍikr, the recital of the confession of faith at appointed times, forms a conspicuous part. Still more remarkable than all this, however, is the chātimah or conclusion which follows these seven faidahs. In this the author, the Abdurraʾuf just referred to, makes himself known to the reader and gives a short notice of his life as a scholar, together with a silsilah (or as the natives pronounce it salasilah) or spiritual genealogical tree, to confirm the noble origin and high worth of his teaching. According to this final chapter, Abdurraʾuf studied for many years at Medina, Mekka, Jiddah, Mokha, Zebīd, Bētal-faqīh etc. He

Among the Malay MSS. which I collected in Acheh, is an abstract made by the author himself of his "Umdat al-muḥtājīn under the name Kifāyat al-muḥtājīn, and also a short refutation of certain heretical dogmas prevalent in these parts in regard to what man sees and experiences in the hour of death. To support his teaching the writer appeals to a work of Molla Ibrahim (successor of Aḥmad Qushāshī) at Medina; of this work I possess a Malay translation by an unknown hand.

Another famous work of this same Abdurraʾuf is his Malay translation of Baidhawi's commentary on the Qurān, published in A. H. 1302 at Constantinople in two handsomely printed volumes. On the title page Sultan Abdulḥamīd is called "the king of all Mohammedans!" From this work we perceive among other things, that the learning of our saint was not infallible; his translation for instance of chap, 33 verse 20 of the Qurān is far from correct. mentions no less than 1§ masters at whose feet he sat, 27 distinguished pandits whom he knew, and 15 celebrated mystics with whom he came in contact.

Aḥmad Qushāshī.Above all others he esteems and praises the mystic teacher Shaikh Aḥmad Qushāshī at Medina. He calls him his spiritual guide and teacher in the way of God, and tells how after his death he (Abdurraʾuf) obtained from his successor Molla Ibrahim permission to found a school himself. Thus after 1661 Abdurraʾuf taught in Acheh, and won so many adherents that after he died his tomb was regarded as the holiest place in all the land, till that of the sayyid called Teungku Anjōng somewhat eclipsed it after 1782.

We noticed above (footnote to p. 10) that the mysticism of Aḥmad Qushāshī was disseminated in the E. Indian Archipelago by a great number of khalifahs (substitutes), who generally obtained the necessary permission on the occasion of their pilgrimage to Mekka. In Java we find innumerable sàlasilahs or spiritual genealogical trees of this tarīqah or school of mystics. In Sumatra some even give their ṭarīgah the special name of Qushashite[28]; and it is only of late years that this Satariah, as it is usually called, has begun to be regarded as an old-fashioned and much-corrupted form of mysticism and to make place for the ṭarīqahs now most popular in Mekka, such as the Naqshibendite and Qadirite.

Satariah.I have called this school of Qushāshī corrupt for two reasons. In the first place its Indonesian adherents have been so long left to themselves,[29] that this alone is enough to account for the creeping in of all manner of impurities in the tradition. But besides this, both Javanese and Malays have made use of the universal popularity enjoyed by the name Satariah as a hall-mark with which to authenticate various kinds of village philosophy to a large extent of pagan origin. We find for instance certain formulas and tapa-rules which in spite of unmistakeable indications of Hindu influence may be called peculiarly Indonesian, recommended for use as Satariah often along with salasilahs in which the names of Abdurraʾuf and Aḥmad Qushāshi appear.

The work of Abdurraʾuf is, however, in accord with orthodox doctrine, albeit his attitude has excited the jealous or envious sneers of many a pandit.

It might cause surprise that the name of Abdurraʾuf should appear in the salasilahs of Qushāshi's teaching not alone in Sumatra but also to a great extent in Java, since as a matter of fact both Javanese and Sundanese imported this ṭarīqah directly from Arabia. But apart from the possibility of Abdurraʾuf's having initiated fellow-countrymen or those of kindred race before leaving Arabia, after he had received permission to form a school, we must remember that before sailing ships were replaced by steamers as a means of conveyance for visitants to Mekka, Acheh formed a great halting-place for almost all the pilgrims from the Eastern Archipelago. The Achehnese used to speak of their country with some pride as "the gate of the Holy Land". Many remained there a considerable time on their way to and fro, while some even settled in the country as traders or teachers for the remainder of their lives.[30] Thus many Javanese may on their journey through, or in the course of a still longer visit, have imbibed the instruction of the Malay teacher.

In the extant copies of his writings Abdurraʾuf is sometimes described as "of Singkel," and sometimes "of Pansur," but it is a remarkable fact that his name is almost always followed in the salasilahs by the words "who is of the tribe of Ḥamzah Pansuri"[31]. I have nowhere indeed found it stated that Abdurraʾuf expressly opposed the teaching of Ḥamzah, but the spirit of his writings shows that he must have regarded it as heretical. One might have supposed that under these circumstances he would at least have refrained from openly claiming relationship with Hamzah. The only explanation I can give of this phenomenon lies in the extraordinary popularity of the name of Ḥamzah, which may have induced the disciples of Abdurraʾuf to avail themselves of this method in order the better to propagate their own orthodox mysticism.

Sleight dissemination of the other ṭarīqahs in Acheh.Abdurraʾuf has undoubtedly had a great influence on the spiritual life of the Achehnese, though it is true that of such mystic systems only certain externals (such as the repetition of ḍikrs at fixed times, and the honour paid to their teachers) are the property of the lower classes. But his works are now little read in Acheh, and adherents of a Shattarite ṭarīqah or school of mysticism are few and far between. The other ṭarīqahs, which in later times caused so great a falling away from the Satariah, cannot boast one whit the more of great success in Acheh. Perhaps the war is to blame for this, but without doubt the Achehnese adherents of the Naqshibandiyyah or Qadiriyyah are of no account as compared with those of West Java or of Deli and Langkat.

On the other hand the tomb of Abdurraʾuf continues to attract crowds of devout visitors, and it is made the object of all kinds of vows which are fulfilled by pious offerings to the saint. This tomb has become the subject of a characteristic legend which shows how little regard the Achehnese pay to chronology.

Legend respecting Abdurraʾuf.Some of them make out Abdurraʾuf to have been the introducer of Islam into Acheh, although this religion was prevalent in the country at least two centuries before his time. Others make him a contemporary of Ḥamzah Pansuri and represent him as the latter's antagonist, as it became a holy teacher to be. The story goes that Ḥamzah had established a house of ill-fame at the capital of Acheh; for no vice is too black to be laid at the door of heretics. Abdurraʾuf made appointments with the women, one after another; but in place of treading with them the path of vice, he first paid them the recompense they looked for, and then proceeded to convert them to the true faith.

§ 3. Present level of learning in Acheh.

From the above remarks it may have been gathered that for more than three centuries the three chief branches of learning of Islam (Figh, Uçul and Taçawwuf, Ach. Pikah, Usuy and Teusawōh) and as a means or instrument to attain them, the Arabic grammar and its accessories have been practised in Acheh. There are just as many at the present day as in earlier times, who have reached a moderate degree of proficiency in this triple learning, and the branch that is studied with especial zeal is the Law, which is also that of the greatest practical utility. Some gather their knowledge in their native country, others undergo a wider course of study in the Straits Settlements or at Mekka.

Learning in Acheh in ancient and in modern times.Whether learning advanced or declined in Acheh during the historical period of which we have some knowledge cannot be definitely ascertained. The fact that such an extraordinary number of Malay writings on the teaching of Islam appeared in Acheh during the 16th and 17th centuries was merely the result of the political condition of the country, as that period embraces the zenith of the prosperity of the port-kings. Among the authors of these works or among the most celebrated mystics, heretical or orthodox, we do not find a single Achehnese name, but only those of foreign teachers. Learned Mohammedans have at all times sought countries where their attainments commanded solid advantages in addition to honour and respect.[32] The activity of these champions, who fought their learned battles in the capital, had but little significance in regard to the scholarly or religious development of the people of Acheh.

Value of the learned writings of Achehnese.It may well be supposed that there were formerly as well as at the present time some teachers of Achehnese race who gave the necessary enlightenment to their countrymen in Malay or Achehnese writings The fame of such works of the third rank, however, is not wont long to survive their authors[33]; and to this must be added the fact that they were always compiled to meet the requirements of a definite period and of a definite public. Pamphlets like those of Teungku Tirò or Teungku Kuta Karang, and books and treatises such as those of Chèh Marahaban (to be more closely described in Chap. II) will not be so much as spoken of half a century hence.

There is one treatise in Malay apparently written by an Achehnese named Malém Itam or Pakèh Abdulwahab[34], in which are collected the principal rules of the law in regard to marriage, and the original of which is fully a century old. Another Achehnese named Mohammad Zain bin Jalāluddin, from whose hand there appeared in Malay an insignificant essay on a subordinate part of the ritual,[35] and one of the innumerable editions of Sanusi's small manual of dogma,[36] appears also to have been the author of a Malay treatise on the Mohammedan law of marriage,[37] which enjoyed the honour of being lithographed in Constantinople in A. H. 1304 under the name Bāb an-nikāḥ (Chapter on marriage). I do not know in what connection this writer stands with Jalāluddin (= Teungku di Lam Gut, see p. 28 below) who in A. H. 1242 (A. D. 1826–27) wrote the Tambihō rapilin (see Chap. II, N°. LXXXVI). It is probably due to chance that his works have not been consigned to oblivion like those of so many others. They are not specially marked by any redeeming traits and are also devoid of local colour, with the exception of an appendix two pages in length attached to Mohammad Zains Bāb an-nikāḥ, containing precepts designed to suit the requirements of Achehnese life.

The most characteristic of these precepts concerns the ṭaqlīd (Ach. teukeulit) i. e. resorting to the authority of the imam of the Ḥanafite school in respect to the marriage of a girl who is a minor and without father or grandfather. The object of the author is to give legal sanction to the peculiar Achehnese custom of the baléʾ meudeuhab.[38]

Study has not declined in Acheh.The study of the teaching of Islam, of what is generally described as "Mohammedan law", has not declined in Acheh, though it has received somewhat of a check during the disturbances of the past 30 years. If such learning is of little value as a qualification for offices such as those of kali[39] and teungku meunasah[40], that is due partly to the adat which makes these offices hereditary, and partly to the fact that the chiefs do not want as kalis too energetic upholders of the sacred law, and to the reluctance of all true pandits to strengthen the chiefs' hands by pronouncing their crooked dealings straight.

Ornamental branches of study.Such branches of study as commentaries on the Qurān (Tafsīr, Ach. Teupeusé) or the sacred tradition (Ḥadīth, Ach. Hadih) which in the earliest times of Islam formed the pièce de résistance of all learning, as it was from them that the people derived their knowledge of the rules of law, have now become more or less ornamental, since the study of the law has been made independent of them. Such ornamental branches of learning are however highly esteemed even in Acheh. Proficient teachers occasionally give instruction in them, but no one thinks of studying these until he has mastered the essentials of Pikah and Usuy.

§ 4. Schools and Student Life.

Student life.The student life of Mohammedans in the Archipelago would furnish an attractive subject for a monograph. The pěsantrèns of Java have indeed been described in a number of essays, but in these nothing is to be found but a superficial view of the question, which has never been closely examined.

No real schools of priests.A capital and wide-spread error in regard to the schools of the Mohammedan religion in these countries is that they are schools of priests[41]. This is absolutely untrue; not only because there are no such things as Mohammedan "priests", but also because, even if we admit the erroneous term "priests" or "clergy" as applied to the pěngulus, naibs, modins, lěbès etc. in Java, the pěsantrèns cannot in any sense be regarded as training-schools for the holders of these offices. Most of the pěngulus and naibs (but not the so-called desa-clergy) have, it is true, attended a pěsantrèn for a time, but there are many who have entirely neglected such instruction. What is still more striking, however, is the fact that the great majority of students in pěsantrèns never think of competing for a "priestly" office; indeed it may be said of ninety per cent of the santri or students that they would be unwilling to fill such offices, and that they rather as a class view those who occupy them with contempt and sometimes even with hatred.

Kyahis and pěngulus.As in Java so also in Sumatra and elsewhere relations are proverbially strained between the gurus or "kyahi" (as they are called in Java) i.e. the non-official or teaching pandits, and the pěngulus and their subordinates, including those officials in other countries whose duties correspond to those of pěngulu in Java.

Those who administer the Moslim law of inheritance and marriage, who control the great mosques and conclude marriage contracts, regard these kyahis and all belonging to them as a vexatious, quarrelsome, hairsplitting, arrogant and even fanatical sort of people; while these teachers and pandits, on their part, accuse the pěngulus of ignorance, worldliness, venality and sometimes even of evil living.

As we have already observed, by far the greater number of the students who frequent the pǒsantrèns or pondoks in Java, the suraus in mid-Sumatra, or the rangkangs in Acheh, is composed of embryo teachers or pandits, who disdain rather than desire office, or of those whose parents set a value on a specially thorough course of religious instruction. Such institutions could only properly be termed "schools for the priesthood" if we might apply the name of priest to all persons who had passed through a course of theological training.

The students.In Acheh as well as in Java there are to be found among the students young men of devout families; sons of the wealthy and distinguished whose parents consider it befitting that some of their children should practise sacred learning; lads who study from an innate love of and impulse towards learning, to contradict which would be esteemed a sin on the part of their parents; some few who are later on to be pěngulus, naibs, teungkus of meunasahs or kalis, though fewer in Acheh even than in Java, since devolution of office by inheritance forms the rule in the former country; and finally those of slender means, who hope to attain through their learning a competence in this world and salvation in the next.

However deep the contempt in which the maléms and ulamas may hold the occupiers of the so-called "priestly offices," sold as these are to Mammon, yet they are not themselves without regard for the good things of this world, and are not slow to seize the opportunity of securing a fair share of the latter for themselves.

Advantages of religious learning.Well-to-do people very often prefer to give their daughters in marriage, with a sufficient provision for their maintenance, to these literati, who are on this account viewed with marked disfavour by the chiefs both in Java and Acheh. All alike occasionally invoke their knowledge or their prayers in times of distress, and such requests for help are always accompanied by the offer of gifts. At all religious feasts—and we know how numerous these are in Native social life—their presence is indispensable, and their attendance is often actually purchased by gifts of money. There are thus numerous opportunities for profit for the ulama or malém, quite apart from the instruction they give, which though not actually "paid for" is still substantially recompensed by those who have the requisite means. To this must be added the honour and esteem liberally accorded to these teachers by the people, who only fear the "priesthood" (wrongly so called) on account of its influence in matters affecting property and domestic life.

None acquire learning in their own gampōng.Just as the Israelites used to say that a prophet is without honour in his own country, so the Achehnese assert with equal emphasis that no man ever becomes an além, to say nothing of an ulama, in his own gampōng. To be esteemed as such in the place of his birth, he must have acquired his learning outside its limits. This is to be explained chiefly by the prejudice natural to man; to recognize greatness in one whom we have seen as a child at play, we must have lost sight of him for some time during the period of his development. To this must also be added the fact that those who remain from childhood in their own gampōng, surrounded by the playmates of their youth, find it harder as a rule to apply themselves to serious work than those who are sent to pursue their studies among strangers.

The same notion is universally prevalent in Java. Even the nearest relatives of a famous kyahi are sent elsewhere, preferably to some place not too close to their parents' home, in order that the love of amusement may not interfere with the instruction they are to receive and that their intercourse may be restricted to such as are pursuing or have already partially attained the same object. Hence the expression "to be in the pondok or pěsantrèn" always carries with it in Java the notion of being a stranger[42]. In Acheh the word meudagang[43], which originally signifies "to be a stranger, to travel from place to place", has passed directly from this meaning to that of "to be engaged in study."

Thus it happens that most of the learned in Great Acheh have spent the greater part of their student life in Pidië, while vice versâ the studiously inclined in Pidië and on the East Coast amass their capital of knowledge in Great Acheh[44].

Achehnese schools of repute.In the territory of Pidië in the wider sense of the word[45], there were, before the coming of the Dutch to Acheh, certain places which were in some measure centres of learned life, where many muribs (the Achehnese name for "student", from the Arab. murīd) both from the country itself and from Acheh used to prosecute their studies. Such were Langga, Langgò, Sriweuë, Simpang, Ië Leubeuë (= Ayer Labu). Tirò, which has in these latter days acquired a widespread celebrity from the two teungkus of that place who took a prominent part in the war against the Dutch, was from ancient times less famed for the teaching given there than for the great number of learned men whom it produced and who lived there[46]. Tirò was as it were sanctified by the presence of so many living ulamas and the holy tombs of their predecessors. None dared to carry arms in this gampōng even in time of war; and the hukōm or religious law was stronger here than elsewhere, while its enemy the adat was weaker. Growing up amid such surroundings, many young men feel themselves led as it were by destiny to the study of the sacred law.

Chèh Saman[47], who of late years was conspicuous in Great Acheh as a leader in the holy war until his death, was the son of a simple leubè from Tirò[48]. The foremost member of an old family of pandits in that place was within the memory of man the Teungku di Tirò par excellence, also sometimes known as Teungku Chiʾ di Tirò. Such was till his death in 1886, Teungku Muhamat Amin, and his relative, the energetic Chèh Saman, was his right-hand man. The latter indeed succeeded him; for at Muhamat Amin's death his eldest son (a learned man who has since died), was still too young to fill his father's place. A younger son of Muhamat Amin is now panglima under the supervision of the well-known Teungku Mat Amin, the son of Chèh Saman. [This Mat Amin with about a hundred of his followers perished in 1896 at the surprise of Aneuʾ Galōng by the Dutch troops.]

In Acheh Proper, before the war, the principal centres of teaching were situated in the neighbourhood of the capital and in the sagi of the XXVI Mukims.

Teungku di Lam Nyòng, whose proper name was Nyaʾ Him (short for Ibrahim), attracted even more followers than his father and grandfather before him, and drew them by hundreds to Lam Nyòng, eager to hear his teaching. He had himself studied at Lam Baʾét (in the VI Mukims) with a guru who owed his name of Teungku Meusé (from Miçr = Egypt) to his sojourn in that country, and at Lam Bhuʾ under a Malay named Abduççamad. Very many Achehnese ulamas and almost all the teachers of the North and East Coasts owe their schooling wholly or in part to him.

After the death of a certain Muhamat Amin, known as Teungku Lam Bhuʾ, and of his successor the Malay Abuççamad, who had wedded the former's sister, a period of energy in learning was followed by one of inactivity. This was all changed by the appearance of Chèh Marahaban[49]. His father was an unlearned man from Tirò, who settled later on the West Coast. Marahaban studied in Pidië (in Simpang among other places) and later on at Mekka, where he acted as haji-shaikh[50] (guide and protector of pilgrims to Mekka and Medina) to his fellow-countrymen. He returned from Arabia with the intention of settling down again in Pidië, but at the capital of Acheh he yielded to persuasion and put his learning at the disposal of Teuku Kali Malikōn Adé[51] and of the less learned kali of the XXVI Mukims. At the same time he became a teacher and a prolific writer[52].

In course of time there arose a clever pupil of the above-named Malay Abduççamad, who received the title of Teungku di Lam Gut[53] from the gampōng of Lam Gut. His proper name was Jalaluddīn. He became not only a popular teacher but also kali of the XXVI Mukims. His son, a shrewd but comparatively unlearned man, inherited his father's title and dignity, but gladly transferred the duties of his office to his son-in-law, the Marahaban just spoken of. The grandson of the old Teungku di Lam Gut, and his surviving representative, is similarly kali in name, but is consulted by none and never poses as a teacher.

At Kruëng Kalé there was a renowned teacher who succeeded his father in that capacity. At Chòt Paya such students as desired to bring their proficiency in reciting the Qurān to a higher level than could be attained in the village schools, assembled under the guidance of Teungku Deuruïh, a man of South Indian origin.

The unsettled condition of the country during the past 26 years has of course completely disorganized religious teaching. In Lam Seunòng such instruction is still given by an old Teungku who takes his name from that gampōng; like him, Teungku Tanòh Mirah, who besides being a teacher is also kali of the IV Mukims of the VII (sagi of the XXVI) acquired his learning at Lam Nyòng. The same was the case with Teungku Kruëng Kalé alias Haji Muda, who studied at Mekka as well. In Seulimeum (XXII Mukims) is a teacher called Teungku Usén, whose father Teungku Tanòh Abèë[54], celebrated for his learning and independence, held the position of kali of the XXII Mukims.

Places of abode of the students.The students, who are for the most part strangers in the place where they pursue their studies, must of course be given a home to live in. Even where their numbers are not told by hundreds it would be difficult to house them all in the meunasah, a building which, as we know, serves as a chapel for the village and as a dormitory for all males whose wives do not live in the gampōng. The intercourse with the young men of the gampōng resulting from lodging under the same roof with them, is also regarded as detrimental to their studies. As a rule, then, the people of the gampōng, on the application of the teacher, erect simple buildings known as rangkangs, after the fashion of the students' pondoks or huts in Java.

Rangkangs.A rangkang is built in the form of a dwelling-house, but with less care; in place of three floors of different elevations it has only one floor on the same level throughout, and is divided on either side of the central passage into small chambers, each of which serves as a dwelling-place for from one to three muribs.

Occasionally some devout person converts a disused dwelling-house into waqf (Ach. wakeuëh) for the benefit of the students. The house is then transferred to the enclosure of the teacher and fitted up as far as possible in the manner of a rangkang.

Assistant teachers.In Java every pondok or hut of a pěsantrèn has its lurah (Sund. kokolot) who maintains order and enforces rules of cleanliness, and enlightens the less experienced of his fellow-disciples in their studies. Similarly in Acheh the teungku rangkang is at once assistant master and prefect for the students who lodge in the rangkang. He explains all that is not made sufficiently clear for them by the teaching of the gurèë. The students are often occupied for years in mastering the subsidiary branches of learning, especially grammar, and here the teungku rangkang is able to help them in attaining the necessary practical knowledge, by guiding their footsteps in the study of Malay pikah and usuy books such as the Masaïlah, Bidayah and Çirāt al-mustaqīm[55].

This establishment of heads of pondoks or rangkangs and the excellent custom among native students of continually learning from one another alone save the system from inefficiency, for the teachers take no pains to improve the method of instruction, and many of them are miserably poor pedagogues in every form of learning.

Method of instruction adopted by the teachers.The ulamas are wont to impart instruction to the students in one of the two following ways. Either the latter go one by one to the teacher with a copy of the work they are studying, whereupon he recites a chapter, adding the requisite explanations, and then makes the pupil read the text and repeat or write out the commentary; or else the disciples sit in a circle round the master, who recites both text and commentary like a professor lecturing his class, allowing each, either during or after the lesson, to ask any questions he wishes.

Sorogan and bandungan.In Java the first of these two systems is called sorogan and the second bandungan. In Acheh the former method is usually followed by the reading of one of the Malay manuals mentioned above under the supervision of the gampōng teacher or of the teungku rangkang, the bandungan method alone being used for the study of the Arabic books. The Achehnese have no special names for these methods of instruction [56].

Uncleanliness of the students.Besides the system of teaching, the Achehnese rangkangs have in common with the Javanese pondoks an uncleanliness which is proverbial—indeed the former surpass the latter in this respect. One might suppose that in such religious colonies, where the laws of ritual purification are much more strictly ohserved than elsewhere, we should find an unusually high degree of personal cleanliness. Experience however shows that a man who limits himself to the minimum requirements of the law in this respect can remain extremely dirty without being accused of neglect of his religious duties. Nor do the laws of purification extend to clothing. The mere ritual washing of the body (often limited to certain parts only, since the complete bath is seldom obligatory, especially where there is no intercourse with women) is of little service, as the clothes are seldom washed or changed and the rooms in which the students live rarely if ever cleaned out.

Such advantage over ordinary gampōng folk as the muribs may possess in regard to cleanliness through their stricter observance of religious law, they lose through their bachelorhood, since they have to manage their own cooking, washing etc.

In Java there are to be found in many pěsantrèns written directions regulating the sweeping out of the huts, the keeping of watch at night, the filling of the water-reservoirs etc., and fines are levied on those who omit their turn of service or enter pondok or chapel with dirty feet, the money being paid into the common chest[57]. Ill-kept though these rules often are, they still render the pondoks and their occupants a little less unclean than the rangkangs and their muribs in Acheh, where the universal dislike of water and habit of dirt have reached an unusually high degree.

In Java gudig or budug (mangy or leprous) is a very common epithet of the students, and the "santri gudig" is even to some extent a popular type. Thus it is not surprising that in Acheh also kudé and suchlike skin-diseases[58], though they are not confined to the students huts, are yet regarded as a sort of hall-mark of the murib.

Influence of the life led by the students on their general development.The general development of the muribs in Acheh derives less benefit from their sojourn in the rangkangs than that of the santris in Java from their wanderings from one pěsantrèn to another. The latter become familiar with their fellow-countrymen of other tribes, as Javanese with Sundanese and Madurese, and their studies draw them from the country into the large towns such as Madiun and Surabaya. They also improve their knowledge of agriculture through planting padi and coffee to help in their maintenance. In Acheh geographical knowledge is confined to narrow limits; as the student only moves about within his own country, intercourse with kindred tribes is not promoted by the meudagang nor does he act as a pioneer of development in any way. He returns home with very little more knowledge of the world than he possessed when he went on his travels; all he learns is an ever-increasing contempt for the adat of his country (which conflicts with Islam in many respects) so that later on, as a dweller in the gampōng, he looks down on his fellow-countrymen with a somewhat Pharasaical arrogance.

It is needless to observe that the morals of the inhabitants of the rangkangs in Acheh are still less above suspicion than those of the pěsantrèn-students in Java.

Popular estimation of the teungkus.Those who have devoted themselves to study and all who have for some reason or other a claim to the title of teungku[59], are regarded by the mass of the people not only as having a wider knowledge of religion than themselves, but also as having to some extent, control over the treasury of God's mercy. Their prayers are believed to command a blessing or a curse, and to have the power of causing sickness or ensuring recovery. They know the formulas appointed of Allah for sundry purposes, and their manner of living is sufficiently devout to lend force to their spoken words. Even when some ignorant leubè is so honest as to decline the request of a mother that he should pronounce a formula of prayer over her sick child, he cannot refuse her simple petition that he will, "at least blow upon it"; even the breath of one who has some knowledge of book-lore and fulfils his ritual duties with regularity, is credited with healing power by the ignorant people.

§ 5. Branches of knowledge not appertaining to the

threefold learning of Islam.

The `eleumèë par excellence, as we have already seen, is the threefold sacred learning (Pikah, Usuy and Teusawōh) with the preliminary branches (Naku etc.), and the supplementary ones such as Teupeusé and Hadih. We have also made a passing acquaintance with an èleumèë which, chiefly owing to the heresy it involves, lies outside learning proper, namely the èleymèë saléʾ[60], There are besides a number of other "sciences" which cannot be regarded as forming a part of "the learning".

These numerous èleumèë's, like their namesakes among the Malays and Javanese (ilmu, ngèlmu), are if viewed according to our mode of thought, simply superstitious methods of attaining sundry ends, whether permissible or forbidden. A knowledge of these is considered indispensable alike for the fulfilment of individual wishes and the successful carrying on of all kinds of callings and occupations. For the forger of weapons or the goldsmith, the warrior or the architect, a knowledge of that mysterious hocus-pocus, the èleumèë which is regarded as appertaining to his calling, is thought at least as important as the skill in his trade which he acquires by instruction and practice. So too he that will dispose of his merchandize, conquer the heart of one he loves, render a foe innocuous, sow dissent between a wedded pair, or compass whatever else is suggested to him by passion or desire, must not neglect the èleumèë's; should he be ignorant of these, he seeks the aid of such as are well versed in them.

Views of religious teachers with regard to the èleumèës.From the point of view of the religious teacher, there is a great difference in the manner in which these various èleumèës are regarded. Some of them are classified as sihé (Arab. siḥr) i. e. witchcraft, the existence and activity of which is recognized by the teaching of Islam, though its practise is forbidden as the work of the evil one. It is just as much sihé to use even permissible methods of èleumèë for evil ends, such as the injury or destruction of fellow-believers, as to employ godless means (such as the help of the Devil or of infidel djéns), although it be for the attainment of lawful objects. The strict condemnation of the èleumèë sihé by religious teaching does not, however, withhold the Achehnese, any more than the Javanese or the Arabs, from practising such arts. Hatred for an enemy and the love of women generally that of the forbidden kind) are the commonest motives which induce them to resort to èleumèës of the prohibited class.

The formulas of prayer and the methods recommended in the orthodox Arab kitabs as of sovereign force are such as might also well be classified under the head of witchcraft, but they are regarded by the Believers as ordained of the Creator. Nor do the Achehnese teachers confine this view to such mystic arts as are marked with the Arabic seal; they also readily employ purely Achehnese material or such as smacks of Hindu influence, so long as they fail to detect in it a pagan origin.

An important source of information in regard to the mystic arts of which we now speak, as practised at the present time in Acheh, is a work called Taj-ul-mulk, printed at Cairo in 1891 (A. H. 1309) and at Mekka in 1893 (A. H. 1311). It was written in Malay by the Achehnese pandit Shaikh Abbas i. e. Teungku Kuta Karang (as to whom see Vol. I pp, 183 et seq., Vol. II Chapter II § 4 etc.) at the instance of Sultan Mansō Shah (= Ibrahim, 1838–1870). It contains little or nothing that may not be found in other Arabic or Malay books of the same description, but furnishes a useful survey of the modes of calculating lucky times and seasons, of prognostications and of Native medical art and the methods of reckoning time which are in vogue in what we may call the literate circles of Acheh.

As the writer is an ulama, he of course abstains from noticing "branches of science" which give clear tokens of pagan origin.

The science of invulnerability.A very important class of èleumèë for all Achehnese, but especially for chiefs, panglimas and soldiers, is that known as èleumèë keubay, i.e. the science of invulnerability. This used also to be held in high esteem in Java, witness the numerous primbons[61] or manuals extant upon this subject. The principles on which this group of eleumèë is based are (1) the somewhat pantheistic scheme of philosophy to which we have alluded above[62] and (2) the theory that a knowledge of the essence, attributes and names of any substance gives complete control over the substance itself.

The science of iron.The combination of these two notions causes a knowledge of the innermost nature of iron (the maʾripat beusòë, as it is called) to form a most important factor in endowing man with the power of resisting this metal when wrought into various weapons. The argument is as follows. All elements of iron are of course present in man, since man is the most complete revelation of God, and God is All. The whole creation is a kind of evolution of God from himself, and this evolution takes place along seven lines or grades (meureutabat tujōh), eventually returning again into the Unity through the medium of man. In the earth then all elements are united and capable of changing places with one another. Now the ,éleumèë of iron has the power of producing on any part of the human body that is exposed to the attack of iron or lead, a temporary formation of iron or some still stronger element that makes the man keubay or invulnerable.

Treatment with mercury.Mercury (raʾsa) is regarded as exercising a mysterious influence over the other metals; hence one of the most popular methods of attaining invulnerability is the introduction of mercury in a particular manner into the human body (peutamòng raʾsa). This treatment can only be successful when resorted to under the guidance of a skilled gurèë. So every Achehnese chief has, in addition to many advisers on the subject of invulnerability, one special instructor[63] known as ureuëng peutamòng raʾsa keubay or raʾsa salèh.

Preparation for the course of treatment.Ordinarily the treatment is prepared for by at least seven days kaluët (doing of penance by religious seclusion) in a separate dwelling near some sacred tomb. These days the patient spends in fasting, eating a little rice only at sundown to stay his hunger. After this begins the rubbing with mercury, generally on the arms, which lasts until a sufficient quantity of mercury has, in the opinion of the gurèë, been absorbed by the patient's body. For the first seven days of his treatment he is further subjected to pantang of various kinds; he must refrain from sexual intercourse, and the use of sour foods, and of bòh jantōng (plantain-buds) ōn murōng (kèlor-leaves) and labu (pumpkin).

Not only during the treatment but also in his subsequent life, the patient must repeat certain prayers for invulnerability at appointed times. Many teachers hold that such duʾas or prayers are only efficacious if they are made to follow on the obligatory seumayangs; some even require of their disciples an extra seumayang in addition to the 5 daily ones to supplement those which they may have neglected during the previous part of their lives. By this means an odour of sanctity is given to their method, while at the same time they have a way left open to account for any disappointment of their disciples' hopes, without prejudice to their own reputation. As a matter of fact very few chiefs remain long faithful to this religious discipline; thus, should they later on be reached by the steel or bullet of an enemy, they must blame their own neglect and not their teacher.

The patron of invulnerability.During the massage the teacher also repeats various prayers. To perfect himself in his calling he has to study the proper traditional methods for years as apprentice to another gurèë, and also to seclude himself for a long period amid the loneliness of the mountains. In this seclusion some have even imagined that they have met Malém Diwa, the immortal patron of invulnerability, with whom we shall become further acquainted in our chapter on literature (N°. XIII)[64].

In many of the systems employed to compass invulnerability, it is considered a condition of success that the pupil should not see his teacher for a period of from one to three years after the completion of the treatment or the course of instruction; indeed it is even asserted that a transgression of this pantang regulation would result in the death of the heedless disciple who disregarded it.

In the night following the first day of the treatment, the patients complain of a heavy feeling in the neck, the idea being that the quicksilver has not yet fully dispersed and collects beneath the back of the head when the patient assumes a recumbent attitude. The remedy for this intolerable feeling is the repetition of a rajah or exorcising formula by the instructor.

To give some notion of the energy with which the mercury is rubbed in, we may mention the popular report that Teuku Nèʾ of Meuraʾsa absorbed 10 katis (about 13 lbs.) of quicksilver into his body through the skin[65].

Objects the wearing of which ensures invulnerability.The "introduction of quicksilver" is, however not the only method employed to produce invulnerability. There are certain objects which have only to be worn on the body to render it proof against wounds.

Peugawè.One class of such objects is known as peugawe. These have the outward appearance of certain living creatures, such as insects, caterpillars, lizards etc., but are in fact composed of iron or some still harder metal, which a knife cannot scratch. They are only to be met with by some lucky chance on the roadside or in the forest. Peugawès having the form of an ulat sangkadu (a long-haired, ash-coloured variety of caterpillar) are very highly prized. The possessor of such a charm, if constrained to part with it, can easily secure a price of as much as two to five hundred dollars.

According to the prevailing superstition, these objects were once actually living creatures, but have become metamorphosed, through the conversion of elements mentioned above, into iron, copper or some other metal. A sort of peugawè can be made by rolling up an ajeumat (= jimat, ajimat "amulet") in a layer of èʾ malò (sediment of gum-lacquer). This too is supposed to be gradually transformed into iron by means of certain formulas, and like other peugawès, renders its wearer wound-proof. A peugawè prepared in this manner has the special name of barōnabeuët (from baḥr an-nubuwwah = the (mystic) sea of prophetical gifts). It is worn on a band round the waist.

If the object found combines with the hardness of iron the form of a fruit or some other eatable thing, it is also called peugawè, but is only of service as a charm (peunawa) against poisons, from the action of which it protects its wearer.

The ranté buy.Another peculiar sort of charm against wounds is the ranté buy (pig's chain). Certain wild pigs called buy tunggay from the fact that they are solitary in their habits, are said to have a hook of iron wire passing through their noses which renders them invulnerable. This is supposed to be formed from an earthworm which the animal takes up with his food, but which attaches itself to his nose, and there undergoes the change of form which converts it into a charm. When the buy tunggay is eating he lays aside this hook, and happy is the man who can avail himself of such a moment to make himself master of the ranté.

According to the devout, however, the efficiency of most peugawès is conditional on the wearers leading a religious life; otherwise the charms merely cause irritation instead of protecting his body.

Peungeuliëh.Bullets the lead forming which changes of its own accord into iron, are called peungeuliëh. Whoever finds one of these infallible charms will be wise to keep it about him when he engages in combat, but not on other occasions, as it will then bring him evil fortune. Hence the common saying, addressed for example to one who arrives just too late for a feast:—"what, have you a peungeuliëh about you?"[66].

Other charms to cause invulnerability.Another charm for turning aside the enemy's bullets is a cocoanut with one "eye" (u sabòh mata) worn about the body[67]. Another keubay-specific is a piece of rattan some sections of which are turned the wrong way. Malém Diwa was so fortunate as to find such an awé sungsang, as it is called, of such length that he was able to fasten it under his shoulders round breast and back. Nowadays such freaks of nature are only to be found of the length of a couple of sections.

Spots on the skin which produce invulnerability.Certain peculiar spots on the skin, generally caused by disease, are also held to be signs or causes of invulnerability. Such for instance are the white freckles known as glum, which remain as scars upon the skin after a certain disease. This disease, (called glum or leuki) is said to begin between the fingers and in the region of the genitals and to cause violent irritation. It is supposed to be infectious[68]. Malém Diwa had seven glums of the favourite shape known as glum bintang or bungòng. Such marks are considered by the Achehnese to enhance the personal beauty of both sexes.

A sort of ring-worm called kurab beusòë or iron kurab, which manifests tself in large rust-coloured and intensely itching spots on the body, is supposed to confer invulnerability, especially if it forms a girdle around the waist. This disease is also very infectious. When it begins to declare itself, the patient is asked by his friends whether he has been having recourse to a duʾa beusòë ("iron prayer"), as it is supposed that the kurab beusòë can be brought about by the mysterious craft connected with iron.

The science of weapons.Where so much depends on the efficacy of weapons as in Acheh, it is not surprising that the èleumèë which teaches how to distinguish good weapons from bad is regarded as of high importance. This art has been to a great extent (though with certain modifications) adopted from the Malays. The Achehnese regard the Malays of Trengganu and the Bugis as the great authorities on the subject.

The forger of weapons has his special èleumèë, which according to our European notions would contribute exceedingly little to the value of their wares, though the Achehnese think quite the contrary. Equally strange but very simple are the expedients resorted to by a purchaser to test the value of a reunchōng, sikin or gliwang. For instance, he measures off on the blade successive sections each equal to the breadth of his own thumb-nail, repeating a series of words such as: paléh (= unfortunate), chilaka, meutuah (= lucky) mubahgia (or chènchala); or tua, raja, bichara, kaya, sara, mati; or sa chénchala, keudua ranjuina, keulhèë keutinggalan, keupeuët kapanasan etc. up to 10.

The word that coincides with the last thumb-breadth, is supposed to give the value of the weapon.

For sikins, the ordinary fighting weapons of the Achehnese, the following test is also employed. The rib of a cocoanut leaf is divided inso sections each equal in length to the breadth of the sikin, and these are successively laid on the blade thus:

Should they when laid upon the blade form a complete row of squares as in the above figure, it is called a gajah inòng (female elephant without gadéng or tusks) and the weapon is esteemed bad. Should there be two pieces too few to complete the last square, thus □‾‾, then it is thought to be superlatively good, as representing the rare phenomenon of an elephant with only one tusk. Should there however be one too few, thus □‾‾, then it is called an elephant with two tusks, and the weapon is considered moderately good at best.

Seers.There is another rich variety of èleumèë, which confer on their possessors the power of seeing what is hidden from ordinary mortals. Those who practise this craft are called "seers"[69] (ureuëng keumalòn). The possessors of this gift are questioned in order to throw light on the cause of, or the best cure for a disease, the fortunes of a relative who has gone on a journey, the thief or receiver of stolen goods and so forth.

The questioner usually offers to the ureuëng keumalòn a dish of husked rice on which are also placed two eggs and a strip of white cotton. The methods employed by the "seers" or clairvoyantes vary greatly. Some draw their wisdom from a handbook of mystic lore, others from the lines produced by pouring a little oil over the eggs presented to them, others again from studying the palms of their own hands.

Invisible helpers of the female "seers".It sometimes also happens (just as in Java) that the clairvoyante invokes the help of an invisible being (ureuëng adara). After the burning of incense, which she inhales or over which she waves her hands, muttering the while, the familiar spirit enters into her. Then she appears to lose her senses; trembling and with changed voice she utters some incoherent sentences, which she afterwards interprets on coming to herself again.

The tiōng as a seer.The mina, a well-known talking bird, called tiōng by the Achehnese, is regarded as endowed with this gift of second sight, but a human "seer" male or female, is indispensable for the interpretation of its utterances. Such clairvoyantes are supposed to understand the speech of the bird, and translate into oracular and equivocal Achehnese the incomprehensible chatter of the mina.

In cases of theft the ureuëng keumalòn usually declares whether the thief is great or small of stature, light or dark of complexion, and whether he has straight or wavy hair[70], so that the questioner has at least the consolation of knowing that the stolen article is not hopelessly lost, and that he may recover it by anxious search.