The Achehnese/Volume 2/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III.

GAMES AND PASTIMES.

§ 1. Various games of young and old.

Childrens' toys.Over the cradles of little children in Acheh are hung sundry objects cut out of paper which charm the infant by their colour and movement and as it were hypnotise him. These are called keumbay bundi. A like purpose is served by boiled eggs coloured red and transfixed with a small piece of stick, with paper ornaments fastened on the top.

In Java they use rattles called klontongan[1] with membranes of paper and a little string on either side to which is attached some hard object. When the wooden handle passing through the drum of the rattle is smartly twisted round, these pellets strike the membrane in quick succession. In Acheh these are known under the name of tèngtòng or geundrang changguëʾ (frogs' drum), as the noise they make bears some resemblance to the croaking of frogs.

Boys play a good deal with tops (gaséng).[2] A kind of humming-top is made from the kumukōih-fruit by thrusting a stick through it by way of axis, and making a hole in the side. The wooden tops resemble our own[3].

The flying of kites[4] (pupò glayang) is a favourite recreation of both old and young. Children play with a simple kind of kite which may also be often seen in Java; in Achehnese they are called glayang tukòng. Grown-up people fly large, but very pretty and more compli-

NATIVE HOUSE: IN THE FOREGROUND A KITE (GLAYANG).

cated kites which are called glayang kleuëng from their resemblance to the kite (the bird). A representation of one of these may be seen in the photograph. Their owners have matches, sometimes for money, as to who can get his kite to rise highest, the cords being of equal length.

Kicking the cocoanut.Meurimbang[5] is the name of a game usually played by two boys one against the other. Each is provided with the top half of a cocoanut shell. Both are set on the ground at a certain distance from one another. One of the opponents kicks his own shell backwards and if he hits that of his opponent a certain number of times he has the privilege of giving his vanquished adversary a rub over the hand with the rough exterior of his shell.

Advantage of winning.The winner's advantage in many of the native games consists in the right to inflict slight bodily tortures like the above. It is thus too for instance with the meusimbang[6], a kind of Knuckle-bones.knuckle-bone game with little stones, usually played by girls. Each stakes a like number of stones, which are thrown up, caught, or lifted off the ground while in motion by all the players in turn according to certain rules. Should any player become "dead", each of the others may smite the back of her hand seven times with the backs of theirs held loosely. The slaps are counted aloud up to seven with the same ceremonious delivery as in the exercise of certain charms[7].

Girls often imitate in play the employments which await them later on as mothers and housekeepers. They sift sand in a piece of the spathe (seutuëʾ) of the betel-nut, pretending that it is rice or rice-flour. Or else the mother makes for her daughter a warp for weaving from the fine innermost coating (seuludang) of this spathe by drawing off alternate strips where it is longest. The daughter is then set to weave this neudòng as it is called, across from left to right with similar stripes. After each insertion the woof is driven home with a slip of wood which serves as peunòʾ ("weaver's rod" = Mal. bělīra). They also weave mats from plantain-leaves. The task of stitching edgings in the mirah-pati pattern |X|X|X|X| stands on the borderland between play and earnest for little girls. The triangular spaces are covered with patches of various colours in imitation of the larger borders used for cushions and curtains.

Dolls.Dolls (patōng) are made from the seulumpuëʾ pisang (plantain-stem). These puppets, on which the little ones lavish their motherly care, are not untastefully dressed up in sundry bright-coloured shreds and patches.

Playing at soldiers.Boys are given imitation weapons as playthings, swords and reunchōngs made of the midrib of the cocoanut leaf, guns from the midribs of the leaves of other palms, and so on. Teungku Kuta Karang in his political pamphlet[8] notices as a characteristic trait of Achehnese children that little boys when howling lustily can be quieted by nothing so well as the sight of a flashing weapon.

Playing at war.It was a custom formerly more common than it now is for young lads, generally of different gampōngs, to have wrestling combats (meulhò) with one another. To start the game a quarrel is picked on purpose[9], and there have sometimes been bones broken and blood spilt in these mimic battles.

Hiding the ring.The game, called meusòmsòm ("covering up") is played with a ring made of rope. One of the players conceals this beneath a heap of sand, and the others must in turn prod for it with a stick. If the stick is found not to have been stuck inside the ring, the first "hider" may hide it again, on which a third player "prods". The winner, i.e. he who succeeds in thrusting his stick within the circumference of the ring, has the privilege of hiding it until another wins.

Game of ball.A favourite game of ball is the meuʾawō. The ball is made by plaiting the young leaves of the cocoanut so as to form a sphere, and filling the interior with some hard material such as clay. Two parties of equal number take up their stand at a suitable interval from one another. The side which opens the game (éʾ, lit. = "to come up") stands near a small stick or rib of the arèn-leaf (puréh) which in the game is known as bu (rice)[10]. From this position one of the players throws the ball backwards over his head in the direction of the opposing side; if they catch it, the first player is "dead". If they fail, the opposite party has now to endeavour to hit the bu with the ball and overthrow it. Should they succeed in doing so, the first player is then dead. Should he survive, he has another turn, but each turn only gives the right to have a single throw. When the whole side is dead, it is succeeded by another.

There are two other games played with balls, on which there is no winning (meunang) or losing (talō), but which only give an opportunity for the display of bodily strength and skill (meuteuga-teuga). These are football (sipaʾ raga) which is also such a favourite pastime amongst the Malays[11], and meulagi. In this last the ball (raga, made of plaited rattan) is thrown into the air by one of the players, after which it is kept going by a smart blow with the hand, all the players doing their best to keep it flying by fresh buffets.

There is another game of meulagi in which a ball (bòh) is thrown up and driven off with a sort of bat (gò) by one side, and then struck back by the other. A variety of this in which a stick about ¾, of a yard long serves as gò and a shorter stick as bòh, is known as meusinggam.

The Achehnese have a combination of our hide and seek[12] and prisoners-base in their mupét-pét or meukō-kō[13], which both girls and boys play together. Two sides of equal number are formed. The first go and hide in different places, while meantime the second keep their eyes shut or their backs turned. One player of the hiding side, however, stays and keeps watch at the bu, for which a tree or some similar object is selected. When the hiders call kō, the seeking begins. The hidden ones however keep leaving their hiding places to "go and eat rice" (pajōh bu), that is to say they run with all possible speed to the tree, when they are safe from being touched by their opponents. If one of the latter succeeds in touching the body of any of the adverse side, or in taking possession of the tree (bu) at a moment when it is left unguarded, the players then change places, and the former seekers must go and hide in their turn.

A guessing game.Meuraja-raja biséʾ (or liséʾ or siséʾ) is another game played by the children of both sexes. Between two sides of equal number stands a neutral raja, sometimes supported by a couple of meuntròës (mantris or ministers) to prevent unfairness on his part.

Each side has also a nang ("mother" or leader) who directs the game rather than takes part in it.

Those on one side choose by agreement which of their fellows is to be pushed into the midst by the nang; and this is secretly communicated to the raja.

A player on the other side now tries to guess the name of the one thus chosen. If he guesses wrong, then a new choice must be made by his own side, but if he guesses correctly, the child in question must go over as "dead" to the other side. The side which are all killed with the exception of the nang, loses the game, which then begins afresh.

The cock on board ship.A variation of the above is to be found in the mumanòʾ-manòʾ kapay or meukapay-kapay ("the cock on board ship" or "ship game"). In this also two sides, each under a nang, take their stand opposite one another. Between them is a mat, on which sits one of the children with his face covered with a kerchief. The nang of the other side comes up to her opponent and asks "what ship is that"? She replies, say, "English". "What is the cargo". "Cocoanut shells". "What else"? "A blind cock". "Let him crow then"! Now the child crows three times as requested, and then the nang of the opposite side must guess who it is. The game then proceeds in the same way as the meuraja-raja biséʾ.

Game of child-stealing.Meusugōt-sugōt[14] or meuchòʾ-chòʾ aneuʾ (child-stealing) is played by girls and also by little boys[15].

All the players but one stand in a row one behind the other, each holding on to the back of the garment of the one in front of her. The foremost is called the nang and must try and prevent the children from being "stolen" by the one who is not in the row and who plays the part of thief. The enemy however always succeeds in the end, in spite of the efforts of the "mother" in touching the children one by one and so compelling them to quit the line as being "dead".

Games with kemiri-nuts.Kemiri-nuts (bòh krèh) are used in various games in Acheh as well as in neighbouring countries[16]. Two sides contend, usually for a wager as to who will first split the other's nut with his (pupòʾ bòh krèh)[17]. There is also a kind of marble-game (Ach. mupadōʾ), in which the bòh krèh is used.

The most favourite pastime however both with young and old is the game called meugatòʾ or mupanta[18], mention of which is to be found in many hikayats. The number of players is not limited, but it can if necessary be played by two. Each player has a bòh gatòʾ or bòh panta, i. e. a betel-nut or a small hemisphere of horn or ivory. Some small holes are made in the ground in a straight line at intervals of from 7 to 9 feet. The players begin by each jerking his bòh panta from the first hole into the third. They shoot the missile by squeezing it hard between the fore finger of the right hand and the middle finger of the left, the elastic pressure of the fingers causing it to spring forward. Whoever succeeds in getting his bòh panta into or nearest of all to the third hole, gets a shot at the others to send them further away from that hole, and so on. The object of the game is to get the bòh panta into all the holes in the row a fixed number of times in the following order; 3, 2, 1, 2, 3, 2, 1 etc. At each shot the player endeavours either to attain the hole next in the sequence, or to knock away his opponent's bòh further from it.

Doing the latter has the double advantage of driving the adversary further from his goal, and of giving the player another shot at the hole, which is much easier than the first as he is now closer up to it.

The first who has got into all the holes in the row the required number of times is called the raja, but those who come after him are also esteemed winners. The last is the only loser and has to stand at the first hole and hold out his ankle (gatòʾ) as a target for the winners (theun gatòʾ). Each of them gets a shot at it from the third hole, not only with his own bòh but also those of all his fellow-players. The luckless member not infrequently becomes quite swollen in consequence of this operation, and it is in any case painful.

The "hopping-game" (hop-scotch; Ach. meuʾingkhé or meungkhé) is played in a good many different ways as regards details; we give here a single example.

A figure is first marked out like that represented on the next page on a small scale. The lines enclosing it are called euë (boundary of land). The four lines drawn from the extremities of the boundary at top and bottom are known as misè (strings); the spaces A—F as rumòh (houses). Each player (there are usually only two) has a fruit of the lumbé or leumbé[19] as a ball to play the game with (bòh). The first player begins by throwing his ball into rumòh A, and then hops up to it without touching

the line (euë) and kicks it back with his free foot. Then he hops back within the boundary close to which he stops, plants his feet together and leaps over it, taking care to land with one of his feet covering the bòh. Should the player in the course of any of these operations come into contact with the euë or the misè, or should he hop badly, or fall or fail to alight on his bòh when he leaps, then he is dead, and the opposite side plays.

If the first turn is successful the same is done with rumòh B and so on till all the spaces have been visited. In kicking back the bòh out of the spaces B—F, it is not counted as a fault if the bòh lands in another rumòh and not beyond the boundaries, always provided that no boundary is touched.

The winning side sometimes refuses to give the losers their revenge except on the condition of the latter's playing their bòh up through the smaller rumòhs on the right of the dotted live ab, which of course gives them a much worse chance.

Playing at fighting.A more serious variation of the wrestling bouts which lads of different gampōngs hold with each other, is to be found in the meutaʾ-tham ("pushing and resisting"). This is also called meukruëng-kruëng "the river-game", as it is often played on the banks of rivers or creeks. In Pidië it is called meugeudeu-geudeu. It is played by full-grown youths, generally of sides chosen from two different gampōngs, and preferably in the evenings or at night at the time of the full moon.

The two sides are composed of an equal number of champions who meet on some wide open space, often in the presence of a great crowd of onlookers. One side (whose task is tham = "to withstand" and dròb = "to catch") is drawn up in line and keeps watch on their opponents. The latter endeavour to give each of their adversaries a push and then to run away at the top of their speed so as if possible to reach a boundary line far in their rear, before being overtaken by one of their enemies. Should one of them succeed in gaining the boundary unopposed after pushing an opponent, then he who received the thrust is reckoned dead; but the latter and his fellows (for more than one may pursue the fugitive) do their best to catch the assailant before he reaches the refuge. He for his part resists his capture with might and main, and none of his own side are allowed to help him. Thus sanguinary battles often occur; when once taken captive the fugitive is dead, whilst he whom he pushed remains alive. As soon as the whole side is dead, the order of the game is reversed.

Keuchiʾs, elders or panglimas are in the habit of attending these fighting games to prevent all serious violence. A prisoner who continues to resist through rage against his fate, they admonish to surrender; and they remind players who indulge in revengeful language through annoyance at a blow or push, that they have joined in the game of their own free will and have no right in any case to cherish revengeful feelings such as might display themselves in earnest when the game was over.

As we see, games savouring of war are very popular in Acheh. But we must not forget that it was necessary for the police to intervene before the main pukulan at Batavia and the prang desa in other parts of Java could be brought within bounds and rendered as harmless as they now are.

A more peaceful variation is the meutaʾ-tham euë galah[20]. A main line is drawn, called euë galah[21] (AB in the figure). This is supposed to be produced indefinitely at both ends. Crossing this at right angles are a number of other lines (euë linteuëng) CD, EF etc., of equal length and separated by equal intervals. Their number depends on the number of players; thus 12 players require 5 euë linteuëng, 14 players 6, and so on. Each euë is guarded by one player, and these guards (6 in number in the figure below) form one side in the game. The other side has to try to make their way from in front of the line L M across all the euës till they get behind the line C D.

On their way they are exposed to the danger of being touched by the guards, in which case they become "dead". The guards of the cross lines must only strike in the direction from which the assailants advance; that of the main line can strike in every direction. In trying to hit his adversary no guard must move further from his line than he can jump with his feet touching. Otherwise his blow does not count.

Should one of the attacking party be touched then all are dead, and the players change places, but if once two of them succeed in passing backwards and forwards unopposed over the space between the lines LM and CD, this is called bilōn and they are the winners.

Rice-mortar game.At the time of the full moon a number of grown girls or young women often assemble to tòb alèë eumpiëng[22], literally = "to pound with eumpiëng-pounders". Each holds in her hand the mid-rib of an arèn-leaf, and with these implements they pound all together in the rice-mortar (leusōng) to the accompaniment of a singsong chant the effect of which is often pleasing to the ear.

Knuckle-bone game.Girls are fond of a sort of knuckle-bone game, played with keupula (pips of the small fruit known in Java as native sawo). This game is called meugeuti, meuguti, or, in some places, mupachih inòng[23], and is almost identical with that called kubuʾ in Java.

Chatō.Another game which is much played by women and children, resembles in principle the Javanese dakon and is played with peukula or geutuë seeds or pebbles. Wooden boards are sometimes used for it, but as a rule the required holes are simply made in the ground, the whole being called the uruëʾ or holes of the game.

The little round holes are called rumòh, the big ones A and B geudōng or chōh and the pips aneuʾ. The game itself is known in different places under the names chatō[24], chukaʾ and jungkaʾ. There are four different ways of playing it in Achéh with which I am acquainted, called respectively meusuëb, meutaʾ, meuchōh, meuliëh. Let us here describe the meusuëb as a specimen.[25]

The two players put 4 aneuʾs in each of six small holes. Then they commence to play, each in his turn taking the pips from any one hole selected at hap-hazard and distributing them among the other holes, dropping one in each they pass.

The direction followed is from left to right for the six holes next the player, and from right to left in the opposite ones. The player takes the contents of the hole he reaches with his last pip, and goes on playing. Should he reach an empty hole with his last pip he is dead.

Should it happen that when the player reaches the last hole which his store of pips enables him to gain, he finds 3 pips therein, he has suëb as it is called, that is to say he may add these 3 to the one he has still remaining and put these 4 as winnings in his geudōng. He can then go on playing with the pips in the next hole (adòë suëb = the "younger brother" of the suëb); but if this next hole be empty he may retain the winnings but the turn passes to his opponent.

Thus they go on until there are too few pips left outside the two geudōngs to play round with. Then each of the players takes one turn with one of the pips which remains over on his own side of the board. If he is compelled to put his pip in one of the holes on the opposite side, he loses it and when all the pips are thus lost the game is finished.

Pachih.Pachih is a favourite game among the men in Acheh. They are well aware that it has been introduced by Klings and other natives of Hindustan. It has been adopted with but slight modifications and even such as there are may also possibly be of foreign origin, for the description of pachisi[26] (= pachih) to be found in G. A. Herklots Qanoon-e-islam, Appx. pp. LVIII–LIX and Plate VII, Fig. 2, differs from the system of play adopted by the Klings now in Acheh, so that it would appear that there are varieties of this game in India also.

Pachih is played with two, three or four persons. Each player sits at one extremity of the cross-shaped pachih-board (papeuën pachih) or pachih-cloth (ruja pachih). Ornamental cloths are sometimes made for this game, with the squares handsomely embroidered. The starting points for the players are the squares A, B, C and D; in these each places his 4 little conical pawōïh which are made of wood, of betelnuts or the like. The players now make throws by turns with seven cowries

which they cast with the hand. These shells must fall either with the opening upwards (meulinteuëng) or downward (teugòm). The value of the different throws is as follows:

| 7 | shells opening upwards | = | 14; | this throw is called | barah |

| 6 | = | 30; | tih | ||

| 5 | = | 25; | pachih | ||

| 4 | = | 4; | |||

| 3 | = | 3; | |||

| 2 | = | 2; | |||

| 1 | = | 10; | |||

| 7 | downwards | = | 7; | chòkah or chòka. |

After each throw the player may move one of his pawōïhs over a number of squares equal to the number of his throw. The direction followed is: from the starting-point, say C, down the middle line of squares to the player, then away from him up the right hand outer line of squares, then continuing along all the outside squares, until he returns to E; thence up the middle squares to the round central space. He who first brings his 4 pawōïhs into the central (dalam or bungòng rayeuʾ) is the winner.

The four throws to which distinctive names are given have, as it is called, a "younger brother" (adòë); that is to say they give the privilege of a fresh throw, but a player may not throw more than three times in succession, and after a throw that has no name the turn passes at once to the next player.

After each throw the player may choose which of his four pieces he will advance. The chief obstacle on the way to the central space consists in this, that when one player's pawōïh reaches a square on which another's is already standing, the latter must retreat to his starting-point (A, B, C or D); it is only in the squares marked thus × which are called bungòng (flower) that several pawōïhs are allowed to stand at once and take their chance.

The tiger game.Certain other games which enjoy a great popularity in Java also under the name of machanan or the "tiger-game" and some varieties of which resemble our draughts, are known

Each moves in turn along the lines of the figure. The tiger may take a sheep each time in any direction or even 3, 5 or 7 from one side of the figure to the other, as for example from K to L or from M. to N.

The game is played on the second figure here represented with 5 tigers and fifteen sheep. A tiger and a sheep are first placed on the board wherever the player likes. Fresh sheep are added one at a time after each move, so long as the supply lasts.

The game ends either when all the sheep are killed, or the tigers hemmed in so as to be unable to move; hence it is called meurimuëng-rimuëng-dòʾ in contradistinction to the next game. The word dòʾ[29] which belongs originally to the verbiage of mysticism and betokens the state of religious ecstasy arrived at in the howling recitations, has in Achehnese the general meaning of "swooning, falling into a faint". So it is applied to the tiger when hemmed in and unable to move.

The third game is called "meurimuëng-rimuëng peuët plōh" ("tiger-game played with forty") as each player puts forty pieces on the board and the pusat (navel) A remains unoccupied. The players may move and take in every direction and so eventually win, though no one is obliged to take if another move appears more advantageous.

As the two sides are exactly equal in number and in privileges, this sort of game of draughts can only in a figurative sense be said to belong to the tiger-games. It is called in Java dam-daman, from the Dutch dam=draughts.

The figures for all these games are usually drawn on the ground, and small stones or the kernels of fruits serve as pieces. Where neces-

The Malays play all three under the name of main rimau or main rimau kambing ("tiger-game" or "tiger and goat-game".) (Translator). sary (as in the case of tigers and sheep for instance) these are of different sizes and colours.

Interchange of games between different peoples.From examples such as that of these tiger-games which have long since acquired a genuine popularity far out among the islands of the Indian Archipelago in spite of their foreign origin, we may see how wide is the spread of such pastimes throughout the world even where civilization is still most primitive and the means of communion and intercourse with other nations few and far between.

In like manner we find the Dutch word knikker (marble) widely diffused in the interior of Java miles beyond any place where European children have ever played.

What is true of childrens' games is without doubt still more applicable to human institutions. This is a fact that should impress on the science of ethnography the necessity for caution in drawing conclusions.

Undoubtedly the ethnography of later times has at its disposal innumerable data which point to the most remarkable results scarcely conceivable in former times, arising from the uniformity of the human organism—results which appear even in the details of man's mental life.

Manners and customs which the superficial enquirer might classify among the most peculiar characteristics of individual races, appear on closer observation to be in reality characteristics of a definite stage of civilization in every region of the globe. The same is true of legends, theories regarding nature and the universe, proverbs etc.

But—the tiger-games and the marbles warn us of it—the fact that games such as these have been so widely spread by borrowing must prevent us too hastily excluding every form of indirect contact or interchange, even between peoples entirely strange to one another.

The examination of apparently insignificant pastimes has a value long since recognized in comparative ethnography and gives us at the same time an insight into the method of training the young practised by different peoples. More than this, in the games of children there survive dead or dying customs and superstitions of their ancestors, so that they form a little museum of the ethnography of the past.

Ni Towong in Java.Of this we find a beautiful example in the Ni Towong in Java. In some districts in that island a figure is composed of a creel or basket with brooms for arms, a cocoanut-shell for head and eyes of chalk and soot, dressed in a garment purposely stolen for the occasion and otherwise rigged out so as to give it something of the human shape. This is placed in a cemetery by old women on the evening before Friday amid the burning of incense, and an hour or two later it is carried away to the humming of verses of incantation, the popular belief being that it is inspired with life by Ni Towong during the above process. Some women hold a mirror before the figure thus artificially endowed with a soul, and after beholding itself there in it is supposed to move of its own accord and to answer by gestures the questions put to it by the surrounding crowd, telling the maiden of her destined bridegroom, pointing out to the sick the tree whose leaf will cure his ailment, and so on.

Children who have often been present and beheld this apparation of Ni Towong, imitate it in their play, and continue to do so even when other superstitions or Mohammedan orthodoxy have relegated the original to obscurity, as is the case in many districts of Java and also at Batavia.

Thus too in all probability ancestral superstitions and disused customs survives in certain other pastimes of the young in Sumatra as well as in Java. They might be described as games of suggestion. We find an example among the Sundanese in Java, who in their momonyetan, měměrakan and similar games impart to their comrades the characteristics of the ape, the peacock or some other animal. The boy who submits to be the subject of the game is placed under a cloth. He is sometimes made dizzy with incense and shaken to and fro by his companions, tapped on the head and subjected to various other stupefying manipulations. Meantime they chant incessantly round him in chorus a sort of rhyming incantation the meaning of which it is impossible fully to comprehend, but in which the animal typified is mentioned by name, and attention drawn to some of its characteristics.

After a while, if the charm succeeds the boy jumps up, climbs cocoanut and other fruit trees with the activity and gestures of an ape, and devours hard unripe fruits with greediness; or else, perhaps, he struts like a peacock, imitating its spreading tail with the gestures of his hands and its cries with his voice till at last his human consciousness returns to him.

When the actual "suggestion" does not take place, it becomes a game pure and simple. The "charmed" boy, when he thinks the proper time has come, merely makes some idiotic jumps and grimaces and perhaps climbs a tree or two or pursues his comrades in a threatening manner.

The children in Acheh also play these games, and it is especially the common ape (buë), the cocoanut monkey (eungkòng) and the elephant whose nature is supposed to be imparted to the boys by means of suggestion[30].

At the time of the full moon young lads sometimes disguise themselves to give their comrades of the same gampōng a fright. Those who make their faces unrecognizable by means of a mask and their bodies by unwonted garments are known as Si Dalupa; where they imitate the forms of animals, they takes their appellation from that which they copy e.g. meugajah-gajah = to play the elephant.

§ 2. Games of Chance.

Amongst the games so far described there are several which are played for love or for money according to preference. There are also, however, a large number of purely gambling games, the issue of which is quite independent of the player's skill, and the object of which is to fleece the opponent of his money.

The passion for gambling betrays itself even among young lads who have no money to stake. Boys whom their fathers send out to cut grass for the cattle often play the „hurling-game" (meutiëʾ) which is won by whoever can knock down or cut in twain a grass-stalk set up at a distance by throwing his grass-knife (sadeuëb) at it. The players wager on the result equal quantities of the grass they have cut; so it often happens that one of the party has no grass left when it is time to go home. Then he hastens to fill up his sack with leaves and rubbish, putting a little grass in on top to cover the deficiency, but should his father detect this fraud the fun of the meutiëʾ is often succeeded by the pain of a sound thrashing at home.

Pitch and toss.As might naturally be expected, there are sundry gambling games which correspond with our "pitch and toss"[31]. For instance meuʾitam-putéh (black or white") so called owing to the Achehnese leaden coins originally used for this game having been whitened with chalk on one side and blackened with soot on the other. The name is still in use, though the two sides of the Dutch or English coins now employed are called respectively raja or patōng ("king" or "doll") and geudōng (store house). In "tossing" (mupèh) one player takes two coins placed close together with their like sides touching each other, between his thumb and forefinger and knocks them against a stone or a piece of wood letting them go as he does so. Should both fall on the same side the person who tossed the coins wins; otherwise his opponent is the victor[32]. There are three sorts of games which may be called banking games, in all of which one of the players or an impartial outsider acts as banker.

1° Meusréng ("twirling"). The banker places a coin on the board on its edge and twirls it. Before it ceases to revolve he puts a cocoanut shell over it. Each player puts his stake on one of two spaces marked on the ground, one of which is called putéh (white) or geudōng and the other itam (black) or patōng. Then the banker lifts the cocoanut-shell, and sweeps in the stakes of the losing parties while he doubles those of the winners[33].

2° Meuchéʾ. In this game the banker takes a handful from a heap of copper money, and counts it to see whether it consists of an odd or even number of coins. The players are divided into sides who stake against each other on the odd or even. The banker often sits opposite the rest and joins in the game as a player without an opponent, or else he takes no part in the game and takes a commission from the rest as recompense for his bankership.

3° Mupitéh. The banker (ureuëng mat pitéh) has in his control 120 pieces of money or fiches (from pitéh = pitis, Chinese coins) and takes a handful from this store. Meanwhile the players stake on the numbers one, two, three and four. The handful taken by the banker is now divided by four, and all win who have staked on the figure which corresponds with the remainder left over, 0 counting as 4. The banker pays the winners twice their stake and rakes in the stakes on the other three numbers as his own profit[34].

Card games.The games with cards are of European origin. Meusikupan[35] (literally "spade game" from the Dutch "schoppen"—"spades") is played with a pack of 52 cards, from which an even number of players receive 5 apiece. Each plays in turn, following not suit but colour; whoever first gets rid of all his cards wins the stake. Meutrōb ("trump game" from the Dutch "troef" = trumps) is played with a pack of 32 which is dealt among 4 players. Each in turn makes his own trumps. Those who sit opposite one another are partners, and the side that gains most tricks wins the game.

Islam and games of chance.As we are aware, every kind of game of chance is most rigorously forbidden by Islam. In Acheh only the leubès and not even all these concern themselves about this prohibition. Most of the chiefs and the great majority of the people consider no festivity complete without a gamble. It is carried so far that even those headmen of gampōngs who as a rule are opposed to gaming in public, shut their eyes to transgressions of this kind on the two great religious feasts which form the holiest days of all the year. Nay more, they actually allow the meunasah, a public building originally dedicated to religion, to be used as a common gaming-house.

Tax on gambling.In former days the ulèëbalangs utilized this prohibition of religious law simply as a means of increasing their revenues. To transgress an order of prohibition within their territory, it was necessary, they reasoned, to obtain their permission. Such licence they granted on payment of 1%, on the amount staked. This source of income was called upat.

Fights of animals.Under the general name of gambling (meujudi) the Achehnese include the various sorts of fights between animals which form with them so favourite and universal a pastime. As a matter of fact it is very exceptional to find such contests carried on simply for the honour and glory of victory.

Nurture of fighting animals.Many chiefs and other prominent personages spend the greater part of their time in rearing their fighting animals.

The fighting bull or buffalo and the fighting ram are placed in a separate stall which is always kept scrupulously clean. They are only occasionally taken out, led by a rope, for a walk or to measure their strength momentarily against another by way of trial. They are most carefully dieted and treated with shampooing and medicaments. When they are being made ready for an approaching fight, a constant watch is kept over them, and the chiefs, lazy as they are at other times, will get up several times in a night to see whether their servants are attending properly to the animals. Rams are taken for quick runs by way of exercise, and are exposed from time to time to the heat of a wood fire which is supposed to rid them of their superfluous fat.

Not a whit less care does the Achehnese noble bestow on his fighting cocks. In the day time they are fastened with cords to the posts underneath the house; but at night they are brought into the front verandah. They too rob their owners of a good deal of their night's rest. The neighbours of these amateurs are often waked at night by the cackling set up by the cocks while they are being bathed and having their bodies shampooed to make them supple; occasionally too they are allowed to fly at one another so that they may not forget their exalted destiny.

The other fighting birds, such as the leuëʾ and the meureubōʾ (both varieties of the dove, called by the Malays těkukur and kětitiran)[36] the puyōh (a kind of quail) and the chémpala are kept in cages; with many princes and ulèëbalangs a leisurely promenade past their prisons takes the place of their devotional exercises in the morning. The daruëts (crickets) are kept in bamboo tubes (bulōh daruët).

No Achehnese devotes a measure of care to the cleanliness, the feeding, the repose and the pleasure of his own child in any way comparable to that he bestows on his scrupulous training of these fighting animals.

The great and formal tournaments of animals are held in glanggangs (enclosures) for which wide open spaces are selected. The arena is either marked off with posts or else simply indicated by the crowd of spectators who group themselves around it in an oval circle or square. Certain fixed days of the week on which fights regularly take place in a glanggang, are called gantòë (succession or turn).

All who desire to enter their animals in a contest against each other in the arena must first obtain the consent of the ulèëbalang in whose territory the glanggang is situated, whereupon they enter into the necessary agreements with one another. All this takes place several days before hand. At the making of the contract each party produces his fighting animal and exhibits it to his opponent in the presence of witnesses. When the stakes have been agreed upon, the two animals are symbolically dedicated to enmity against one another in the future by being allowed for a moment to charge each other with their heads down, or (in case of birds) to peck at each other.[37] The animals are, after this ceremony, said to be "betrothed" (meutunang or lam tunang), while the owners are said to have "made this stake" (ka meutarōh).

The stake of each pair of opponents is called tarōh baʾ = principal stake, and is handed over to an ulèëbalang or keuchiʾ (who usually deducts a commission for his trouble) to be delivered to the winner after the fight is over. Outsiders may in the meantime, both before and during the fight, lay wagers with one another on its issue; the amounts bet are called tarōh chabeuëng or additional stakes. Thus even in the midst of the struggle the betting men may be seen moving about through the crowd, while their cries "two to one, three to two!" and so on, alternate with the tide of battle within the glanggang[38].

Final preparations.The final preparation of the animals for the fight savours a good deal of superstition. Not only is the choice of strengthening and other medicines controlled by superstition, but ajeumats (charms) are employed by the owner to make his animal proof against the arts of witchcraft by which the opponent is sure to endeavour to weaken and rob it of its courage. The kutikas or tables of lucky times and seasons are resorted to in order to decide at what hour of the appointed day it will be best to start for the scene of the combat, and in what direction the animal shall issue from its stall.

Juara.The animals are in the charge of their masters who however usually

Cockfighting.

These bring the animals to the scene of the encounter armed with all sorts of strengthening and invigorating appliances so as to render them service both before the fight and between the rounds.

To guard against the possibility of the adversary having buried some hostile talisman under the earth of the fighting-ring, the servants of each party go diligently over the ground every here and there with ajeumats which they pull over the surface by strings so as to drive away evil influences.

Fighting-birds are held in the hand by their juaras while both parties indulge in one or two sham attacks pending the time for the real onslaught the signal for which is given by the cry "Ka asi": "it is off". So long as this cry has not been heard, either party may hold back his bird to repair some real or fancied omission.

The first release of the birds is a critical moment, and each side tries to get its bird worked up to the proper pitch for it.

Errors in supervision, committed by one party and ascribed by the other to wilful malice, have led to sanguinary encounters and even to manslaughter.

Another stimulus to quarrels over the sport lies in the cries of applause (suraʾ) of the side whose cock seems to be winning. Should its opponents imagine that they see something insulting in the words used, or should the language be derogatory to the dignity of the owner of the losing bird, reunchongs and sikins will be promptly drawn.

Should one of the rival birds become exhausted, its juara and his helpers make every conceivable effort to instil new life into it by speaking to it, by spitting on it, by rubbing it, and so on. If the bird continues to lie helpless and breathless, or should it shun its foe and seek to escape from the fighting-ring, then the combat is decided against it.

To a European spectator there is something ridiculous in the different ways in which the juaras and others urge on their fighting-cocks. One sees greybeards dance madly round a yielding cock and hurl the bitterest insults at it: "dog of a cock! is this the way you repay all the trouble and care spent on you! Ha! that's better! So's that! Peck him on the head!" and so on. In reality however, these doings are no sillier than the excitement which racehorses and jockeys seem capable of arousing in a certain section of the European public.

If both the combatants decline to renew the fight after several rounds are over, the fight is said to be sri; in other words it is drawn.

The fights between chémpalas, meureubōʾs and puyōhs rank as belonging to a lower plane of sport than those of bulls, buffaloes, rams, cocks and leueʾs, while combats between crickets are officially regarded as an amusement for children[39]. For all that, older people are said not to disdain this childish sport; indeed it was said of the Pretender-Sultan that he was a great patron of fights between daruët kléng[40], and often staked large sums upon the sport. According to what people say, it was due to this propensity that gambling was permitted within the house, since the young and lively tuanku would have been put to shame before his old guardian, Tuanku Asèm, if he openly indulged in such unlawful pleasures at a time when stress was being laid on the abandonment of the godless Achehnese adats[41].

Even when free from wagers and matches these pleasures are forbidden by Islam; how much more then when the two sins are inseparably intertwined! Under the war-created hegemony of the Teungkus, fights between animals are becoming rarer and rarer, to the great disgust of many chiefs and of most of the common people. These last fancy that it it is sufficient if these fights are held outside the limits of consecrated ground and on days other than the Friday.

In former times there seem to have been individuals who besides taking part in the ritual of divine service, had no compunction about actively sharing in these sports. At least in the historical hikayats we now and then come across persons bearing the appellation of leube juara, a combination which from an orthodox standpoint seems irreconcilable.

§ 3. Ratébs.

Character of the Achehnese ratébs. To those well versed in the lore of Islam and not trained up to Achehnese prejudices and customs, the ratébs of the Achehnese present the appearance of a kind of parody on certain form of worship.

In the connection in which we here employ it, the word ratéb (Arab. rātib)[42] signifies a form of prayer consisting of the repeated chanting in chorus[43] of certain religious formulas, such as the confession of faith, a number of different epithets applied to God, or praises of Allah and his Apostle. These ratébs are not strictly enjoined by the religious law, but some of them are recommended to all believers by the sacred tradition, while others appertain to the systems established by the founders of certain tarīqahs or schools of mysticism.

The rātib Sammān in the Eastern Archipelago.One rātib, which was introduced at Medina in the first half of the eighteenth century by a teacher of mysticism called Sammān whom the people revered as a saint, enjoys a high degree of popularity in the Eastern Archipelago. The same holy city was also the sphere of the teaching of another saint, Aḥmad Qushāshī, who flourished full half a century early (A. D. 1661), and whose Malay and Javanese disciples were the means of spreading so widely in the far East a certain form of the Shaṭṭārite tarīqah or form of mysticism.[44] The latter teacher's influence was more extensive and had a greater effect on the religious life of the individual. The teaching conveyed by this Satariah to the majority of its votaries is indeed confined to the repetition of certain formulas at fixed seasons, generally after the performance of the prescribed prayers (sěmbahyang); but many derive from it also a peculiar mystic lore with a colour of pantheism, which satisfies their cravings for the esoteric and abstruse.

Muḥammad Sammān and Aḥmad Qushāshī.It was not the intention of Muḥammad Sammān any more than of Aḥmad Qushāshī to introduce any really new element into the sphere of mysticism; their object was rather to attract greater attention to, and win fresh votaries for, the methods of the earlier masters which they taught and practised. The results of the labours of the two, as evidenced in Indonesia, are of a very different nature. The writings or oral traditions of the spiritual descendants of Qushāshī in these countries are restricted to brief treatises on mystic bliss or more extended works on the training of mankind to a consciousness of their unity with God, while the outward manifestation of this Satariah is confined to the observance of certain simple and insignificant seasons of devotion.

The Samaniah was productive of votaries rather than of actual adepts, but wherever the former are, their presence makes itself at once felt. In the evenings and especially that which precedes Friday, the day of prayer, they assemble in the chapel of the gampōng or some other suitable place and there prolong far into the night the ḍikrs known as rātib, chanting the praises of Allah with voices that increase gradually in volume till they rise to a shout, and from a shout to a bellow. The young lads of the gampōng begin by attending this performance as onlookers; later they commence to imitate their elders and finally after due instruction join in the chorus themselves.

Noisy character of the rātib Sammān.Shaikh Sammān, the originator of this rātib, both composed the words and laid down rules as to the movements of the body and the postures which were to accompany them. There can be no question but that this teacher of mysticism held noise and motion to be powerful agents for producing the desired state of mystic transport. In this he differred from some of his brother teachers, who made quiet and repose the conditions for the proper performance of their ḍikrs. His disciples, however, have in later times gone very much further than their master in this respect, and such is especially the case with the votaries of the rātib Sammān in the Malayan Archipelago.

All orthodox teachers, even though they may be indulgent in the matter of noisiness in the celebration of the rātib and excessive gymnastic exercise of the members of the body as an accompaniment thereto, require of all who perform rātib or ḍikr, that they pronounce clearly and distinctly the words of the confession of faith and the names and designations of God; wanton breaches of this rule are even regarded by many as a token of unbelief. But in the East Indian Archipelago the performers of the rātib Sammān have strayed far from the right path. In place of the words of the shahādah, of the names or pronouns (such as Hu i. e. He) used to designate Allah, senseless sounds are introduced which bear scarcely any resemblance to their originals. The votaries first sit in a half-kneeling posture, which they subsequently change for a standing one; they twist their bodies into all kinds of contortions, shaking their heads too and fro till they become giddy, and shouting a medley of such sounds as Allahu éhé lahu sihihihihi etc. This goes on till their bodies become bathed with perspiration, and they often attain to a state of unnatural excitement, which is by no means diminished by the custom observed in some places of extinguishing the lights.

Nasīb.The different divisions of these most exhausting performances are separated from one another by intervals during which one of those present recites what is called a nasib. The proper meaning of this Arabic word is "love-poem". In the mystic teaching it is customary to represent the fellowship of the faithful with the Creator through the image of earthly love; these poems are composed in this spirit which combine the sexual with the mystic, or else love-poems are employed the original intention of which is purely worldly but which are adopted in a mystic sense and recited without any modification.

The nasib in Indonesia has wandered still further from its original prototype than is the case in Arabia. In place of Arabic verses we find here pantuns in Malay or other native languages, tales or dialogues in prose or verse, which have little or nothing to do with religion. Such a piece is recited by one or two of those present in succession, and the rest join in with a refrain or vary the performance by yelling in chorus the meaningless sounds above referred to.

Hikayat Sammān.Histories of the life and doings of the saint Sammān are also very popular in the Archipelago. These tales are composed in Arabic, Malay and other native languages and contain an account of all the wonders that he wrought, and the virtues by which he was distinguished. They are generally known as Hikāyat or Manāqib Sammān ("Story" or "Excellences" of Sammān). They are valued not merely for their contents; their recitation in regarded as a meritorious task both for reader and listeners, and vows are often made in cases of sickness or mishap, to have the hikayat Sammān recited if the peril should be averted. The idea is that the saint whose story is the object of the vow, will through his intercession bring about the desired end[45].

The ratéb Saman in Acheh.In Acheh, as in the neighbouring countries, the ratéb Saman is one of the devout recreations in which a religiously inclined public takes part in spite of the criticism of the more strict expounders of the law. The Achehnese would certainly deny us the right to classify this ratéb under the head of games and amusements nor should we include it in this category were it not that a description of this ratéb is requisite as an introduction to our account of those others, which even the Achehnese regard as corruptions of the true ratéb Saman, without any religious significance. They also declare that while the real ratéb Saman may be the subject of a vow, neither of those secular ratébs which we are now about to describe can properly become so.

In Acheh, as in other Mohammedan countries[46], what is called the "true" ratéb Saman is noisy to an extreme degree; the meunasah, which is the usual scene of its performance, sometimes threatens to collapse, and the whole gampōng resounds with the shouting and stamping of the devotees. The youth of the gampōng often seize the opportunity to punish an unpopular comrade by thrusting him into the midst of the throng or else squeezing him against one of the posts of the meunasah with a violence that he remembers for days to come. There are no lights so that it is very difficult to detect the offenders, and in any case the latter can plead their state of holy ecstasy as an excuse!

The composition which does duty as nasib (= nasīb, see p. 218 above) is to outward appearance devoted to religious subjects, but on closer examination proves to be nothing but droll doggerel, in which appear some words from the parlance of mysticism and certain names from sacred history.

Women's ratéb.The women have a ratéb Saman of their own, differing somewhat in details from that of the men, but identical with it in the main.

The part of the performance called meunasib ("recitation of nasīb") among the men is in the women's ratéb designated by the verb menchakri or meuhadi. The mother in her cradlesong prays that her daughter may excel in this art.

Specimens of the ratéb Saman.We may here give a small specimen of each of these interludes to the ratebs. Like almost every composition in the Achehnese language they are made in the common metre known as sanjaʾ. The following is a sample of nasib from a men's ratéb[47]:

"The holy mosque (i. e. that at Mekka), Alahu, Alahu, in the holy Mosque are three persons: one of them is our Prophet, the other two his companions. He sends a letter to the land of Shām (Syria), with a command that all Dutchmen shall become Moslems. These Jewish infidels[48] will not adopt the true faith, their religion is in a state of everlasting decay".

The following is a sample of chakri from a wemen's ratéb[49]:

"In Paradise how glorious is the light, lamps hang all round; the lamps hang by no cord, but are suspended of themselves by the grace of the Lord."

There is one variety of the ratéb Saman which far surpasses the ordinary sort in noisiness. This is performed more especially in the fasting month at the meudarōïh, when the recital of the Qurān in the meunasah is finished. The assembled devotees recite their ḍikr first sitting down, then standing and finally leaping madly; from two to four of those present act as leaders and cry leu ileuheu, the rest responding ilalah; the words: hu, hu, ḥayyun, hu ḥayat also form part of the chorus.

Ratéb Mènsa.This ratéb is called kuluhét but more commonly mènsa by the Achehnese, who do not however know the real meaning of either word. Mènsa is, as a matter of fact, the Achehnese pronunciation of the arabic minshār = "saw". In the primbons or manuals of Java we actually find constant mention made of the ḍikr al-minshārī i. e. the "saw-dikr"; this is described in detail, and one explanation given of the name is that the performer should cause his voice on its outward course to penetrate through "the plank of his heart" as a carpenter saws through a wooden board. These descriptions are indeed borrowed from a manual of the Shaṭṭarite ṭarīqah[50], but the idea is of course applicable to any ṭarīqah, and the Achehnese have applied the "saw" notion as an ornamental epithet of the ratéb Saman.

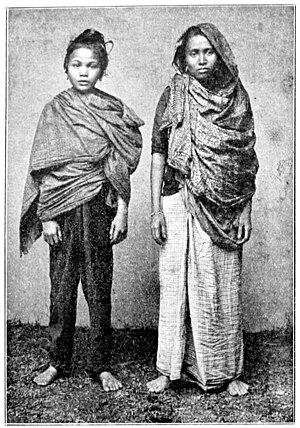

The ratéb sadati.The ratéb sadati is the most characteristic and at the same time the most favourite caricature of the religious ratéb met with in Acheh[51]. It is performed by companies of from 15 to 20 men accompanied by a pretty little boy in female dress who has been specially trained for the purpose. The men composing each company always come from the same gampōng; they are called the daléms, aduëns or abangs i.e. "elder brothers" of the boy, while the latter shares with the ratéb itself the name of sadati.

Each company has its chèh (Arab. shaich) who is also called ulèë ratèb (chief of the ratéb) or pangkay or baʾ (director or foreman) and one or two persons called radat[52], skilled in the melody of the chant (lagèë) and the recitation of nasib or kisahs.

Training of the boys.The boys who are trained for these performances, are some of them the best-looking children of Nias slaves, while others are the offspring of poor Achehnese in the highlands. It is said that these last used sometimes to be stolen by the daléms, but they were more generally obtained by a transaction with the parents, not far removed from an actual purchase. The latter were induced by the payment of a sum of money to hand over to his intended "elder brethren" the most promising of their boys as regards voice and personal beauty. The parents satisfy their consciences with the reflection that the boy will be always finely dressed and tended with the utmost care, and that as he grows up he will learn how to provide for himself in the future.

Origin of the name sadati.The following is the most probable origin of the name sadati. In Arabic love-poems, both those which are properly so called and those which are employed as a vehicle for mysticism, the languishing lover often makes his lament to his audience whom he addresses with the words yā sadāfi (Arabic for "Oh, my masters!"). Such expressions, much corrupted like all that the Achehnese have borrowed from abroad, also appear in the sadati poetry. Hence no doubt the name. of sadati came to be applied both to the ratéb itself, and later on to the boy who takes the leading part therein.

The sadati poetry.A considerable portion of the poetry recited by the sadatis and their daléms is erotic and even paederastic in character; while the sadati himself in his female garb forms a special centre of attraction to the onlookers. But it is a mistake to suppose that the profession of sadati implies his being devoted to immoral purposes.

The morals of the sadatis.The view taken by the daléms is that both the voice and the personal charms of their charge would quickly deteriorate if he were given over to vicious life. They have devoted much time to his training and much money to his wardrobe, and they take good care that they are not deprived prematurely of the interest on that capital, in the shape of the remuneration they receive from those who employ them as players.

The sadati-performance a contest.The ratéb sadati always takes the form of a contest; two companies from different gampōngs, each with their sadatis, are always engaged and perform in turns, each trying to win the palm from the other.

The passion of the Achehnese for these exhibitions may be judged from the fact that a single performance lasts from about eight p. m. till noon of the following day, and is followed with unflagging interest by a great crowd of spectators.

We shall now proceed to give a brief description of a ratéb sadati. To avoid misconception of the subject we should here observe, that a ratéb of this description witnessed in Acheh by Mr. L. W. C. van den Berg in 1881, was entirely misunderstood by him[53].

First of all, this performance was given at the request of a European in an unusual place, and thus fell short in many respects of the ordinary native representation; and in the next place Van den Berg only saw the beginning of the ratéb duëʾ, and those who furnished the entertainment found means to cut it short by telling him, in entire conflict with the truth, that the rest was all the same. Nor were these the only errors into which he fell. In the pious formulas recited by the chèh or leader by way of prologue, the names of all famous mystic teachers, (and among them that of Naqshiband) are extolled. Hearing this name he rushed to the conclusion that this was a mystic performance of the Naqshibandiyyah. The first Achehnese he met could have corrected this illusion had he enquired of him; and had the person questioned had some knowledge of the Naqshibandiyyah form of worship (which, by the way, is little known in Acheh) he would have added this further explanation that this mystic order is strongly opposed to that noisy recitation which is just the special characteristic of the ratéb Saman and of the radéb sadati which is a corruption of the latter.

Mounting of the performance.In the enclosure where the performance is to take place, a simple shed is erected with bamboo or wooden posts and the ordinary thatch of sagopalm leaves. In this the two parties take up their position on opposite sides. The daléms or abangs of one party form a line, in the middle of which is the leader (chèh = Arab shaich, ulèë, pangkay or baʾ). Behind them sit one or more of those who act as radats. Still further in the background is the sadati, already clothed in all his finery; he generally lies down and sleeps through the first portion. of the performance, as he is not called upon to play his part till after midnight.

The sitting ratéb.The prelude is called ratéb duëʾ or "sitting ratéb", since the daléms adopt therein the half-sitting, half-kneeling position assumed by a Moslim worshipper after a prostration, in the performance of ritual prayers (sěmbahyang).

One party leads off, while the other joins in the chorus, carefully following the tune and exactly imitating the gestures of their opponents.

The earlier stage of the recitation consists of an absolutely meaningless string of words, which the listeners take to be a medley of Arabic and Achehnese. Some of these pieces are in fact imitations of Arabic songs of praise, but so corrupted that it is difficult to trace the original. The names of the lagèës or "tunes" to which the pieces are recited, are also in some instances corrupted from Arabic words.

Task of the radat.At the beginning of each division of the recitation, the radat of the leading party sets the tune, chanting somewhat as follows;—ih ha la ilaha la ilahi etc.; the others take their cue from him, or if they forget the words, are prompted by their chèh and all join in.

As to this stage of the proceedings we need only say that the first party chants a number of lagèës (usually five) in succession, and that in connection with many of these chants there is a series of rythmic gestures (also called lagèë) performed partly with the head and hands and partly with the aid of kerchiefs. The following are the names of a group of lagèës in common use:

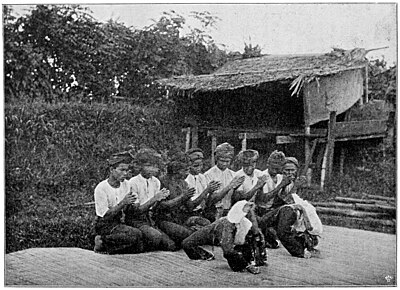

REHEARSAL OF SADATI-PLAYERS, (RATÉB DUËʾ).

Lagèës of the sitting ratéb.

| 1°. | Lagèë asòë idan[54], without any special gestures. |

| 2°. | Lagèë sakinin, accompanied by the lagèë jaròë ("hand tune"), i.e. an elegant series of movements of the hands performed by all in perfect time and unison, punctuated by the snapping of the fingers. |

| 3°. | Lagèë baʾdō salam[55], accompanied by the lagèë ija bungkōïh ("tune of the folded kerchiefs"), in which each performer has before him a twisted kerchief which he gracefully manoeuvres in time with the chanting of his comrades. |

| 4°. | Lagèë minidarwin, accompanied by the lagèë ija lhōʾ ("tune of interwoven kerchiefs"). Each performer interlaces his kerchief with that of his neighbour; sometimes a chain of kerchiefs is thus formed. Later on they are disunited again and spread out in front of their several owners. |

| 5°. | Lagèë salala[56], accompanied by the lagèë ija baʾ takuë (tune of the kerchiefs on the neck). Here the kerchiefs are repeatedly drawn over the shoulders and round the throat. |

These five examples will suffice to give some notion of how much of the real rateb there is in this performance; it will be seen that we did not go too far in characterizing the latter as a caricature of the true ratéb, which is a chant in praise of God and his apostle. The "nonsense verses" to which these lagèës form the accompaniment are repeated over and over again, time after time, until the leading party has exhausted all the gymnastic exercises at its command in respect of that particular tune.

Nasib of this ratéb.As soon as the first ratéb duëʾ is finished an expert of the same party which has hitherto taken the lead in the performance, commences to "meunasib". The nasib of the ratéb sadati consists of a dialogue between the two parties, beginning with mutual greetings, after which it takes the form of question and answer. The questions are in outward appearance of a religious or philosophical nature, but as a matter of fact the nasib is as much a caricature of a learned discussion as the whole ratéb is a travesty of a service of prayer and praise. The players, however, as well as most of the audience, who have but little knowledge

REHEARSAL OF SADATI-PLAYERS, (RATÉB DUËʾ)

of the intricacies of Mohammedan law, regard the performance as actual earnest, and the former endeavour to injure their opponents by paltry invective, by difficult questions and unexpected rejoinders.

Kisah in conclusion of the nasib.After each nasib, that is to say after each of these dialogues consisting of a preliminary greeting followed by question and answer, the leading party gives what is called kisah ujōng nasib or story in conclusion of the nasib. An expert story-teller chants his tale by half-verses at a time, each half-verse being taken up and repeated by the rest of his company. In this respect it resembles certain of the ḍikrs which are recited in chorus.

Specimen of nasib with the accompanying kisah.We append a specimen of one of these dialogues of salutation, and of the question and answer which follow, together with the kisahs which appertain thereto; observing at the same time that this part of the performance is often considerably prolonged. It also frequently happens that one party plays out its part to the end before the other intervenes, after which the first one does not again enter the lists until after the conclusion of the whole nasib.

Salutation.Salutation of the party A. God save you all, oh teungkus, I wish to convey my salutation to all of you. I would gladly offer you sirih, but I have not my sirih-bag with me; I have come all the way from my gampōng, which lies far away. I wished to offer you sirih, but I have no betel-bowl; I cannot return (to fetch it), it is now too late in the day. In place of giving you sirih then, oh worshipful masters, I lay both my hands upon my head (in token of respect). My ten fingers on my head, to crave forgiveness of you all, oh teungkus. Ten fingers, five I uplift as flowers[57] upon my head.

Kisah.Kisah in conclusion of this nasib. Near the Meuseugit Raya there is a mounted warrior of great bravery who there performed tapa (penance with seclusion). He did tapa there in the olden days when our country (Acheh) began its existence; of late he has come to life again. For many ages he has slumbered, but since the infidel has come to wage war against us, he has waked from his long sleep. Seek not to know this warriors real name; men call him Nari Tareugi. The white of his eyes is even as (black) bayam-seed, their pupils are (red) like saga-seeds. In his hand he holdeth a squared iron club; there is no man in the world who can resist his might. The place where he takes his stand becomes a sea; a storm ariseth there like unto the rainstorms of the keunòng sa[58]. The water around him ebbs and flows again. Thus shall you know the demon of the Meuseugit Raya.—In the Darōy river is a terrible sanè[59]; let no man suffer his shadow to fall on him, lest evil overtake him.—In the Raja Umòng[60] is the sanè Chéʾbréʾ[61], over whom no human being however great his strength, can prevail.

Answering salutation.Answering salutation of the party B. Hail to you, oh noble teungkus! I lay my hands upon my head.

Here followeth the salutation ordained by the sunat for the use of all Moslims towards a new-comer, come he from where he may[62].

I wish to salute you in token of respect, I stretch forth my hands as a mark of my esteem. I make three steps backwards in token of self-abasement, for such is the custom of the gently bred. My teacher has instructed me, teungkus, first to make salutation and then to welcome the new-comer. After the salutation I clasp your hands; last follows the offering of sirih.

Kisah.Kisah in conclusion of this nasib. Hear me, my friends, I celebrate the name of Raja Beureuhat. A marvellous hero is this Raja Beureuhat, unsurpassed throughout the whole world. When he moves his feet the ground shakes; when he raises up his hands there is an earthquake. On the sea he has ships, and steeds upon the land. Now I turn to wondrous deeds[63]. In Gampōng Jawa the heavens are greatly overcast; storms of rain and thunder and lightning come up. Cocoanut trees are cleft in twain; think upon it, my friends who stand without. But I would remind you that if you will not enter the lists with us, it is better to wait. If there are any among you teungkus, that are ready to match themselves against us let them marshal their ranks. If their ranks are not in proper order, then will I have no relationship with you (i. e. you are not worthy opponents). Ask them (the rival party; here the speaker appears to address the audience) whether they indeed dare to do battle with us; if so let them get ready their weapons and put their fortifications in a state of defence. Their fort must be strong, and their guns must carry far, for here with us we have bombs of the Tuan beusa[64].

Nasib in the form of a doctrinal question.Nasib of the party A in the form of a question. There was once a man who slept and dreamed that he had committed adultery; afterwards he went down from his house and went to the well but found no bucket there. Thence he went to the mosque (to fetch a bucket); how then did he express the niët (= "intention", the Arab. niyyat, which every Mohammedan has to formulate as the introduction to a ritual act, and so as in the present case to the taking of a bath of purification)? How many be the conditions, oh teungkus of such a ritual ablution? In this jar are all kinds of water[65]. Let not the jar be broken, let not its covering (say of leaves or cotton) be open; what, oh teungkus are the conditions of a valid ritual ablution?

The same party A now follows with a short story, a kisah ujōng nasib; for brevity's sake we shall pass this over and go on to the answer of the opposite party.

Nasib in reply to the question.Nasib of the party B in the form of an answer. If Allah so will[66], I shall now answer your question. Set me no learned questions; I cannot solve them, I am no doctor of the law[67]. Answer me first, oh teungku, and answer me correctly, how many conditions there be to the setting of a question. Without conditions and all that depends on these conditions, your questioning is in vain. Not till the conditions and that which depends on them is known, has the asking of questions any meaning. Grammar (is taught) at Lam Nyòng, the learning of the law at Lam Puchōʾ; elsewhere there are no famous teachers; come, sound our depth! Logic is taught at Lam Paya, dogma at Kruëng Kalé; your questions are put without consideration. On the mountains there are sala-trees, on the shore there are arōn-trees; the waves come in and pile up the sand. Take some rice (provision for the travelling student) and come and learn from me even though I teach you but one single little line. At Kruëng Kalé there are many teachers, Teungku Meusé[68] is as the lamp of the world. They (these great teachers) have never yet entered into a contest with any man with learned questions; to do so is a token of conceit, ambition, pride and vain-glory[69]. Conceit and ambition, pride and vain glory, by these sins have many been brought to destruction. People who are well brought up are never made a prey to shame; those who trust in God are never overtaken by misfortune. Others have propounded many learned questions, oh my master, but never such foolish ones as thou. With a single kupang (one-eighth of a dollar) in thy purse, thou dost desire to take all the land in the world in pledge[70]; others possess store of diamonds and set no such value on their wealth as thou.

The second sitting ratéb.Hereupon follows the kisah of the party B, and after this or after the nasib has been pursued still further in the same manner, it becomes the turn of the party B to take the leading part. Immediately after the latter has recited their last kisah, it begins its ratéb duëʾ, and now the party A which previously took the lead must exhibit its skill in following quickly and without mistakes the tunes, gestures and gymnastic play with hands and kerchiefs, which their opponents have previously rehearsed and can thus perform with ease.

The ratéb thus runs again exactly the same course as that we have just described, only with a change of rôles, and with certain variations which do not affect the essence of the performance.

The standing ratéb. Commencement of the sadatis' perfomance.As soon as this is all finished, the ratéb duëʾ is succeeded by the ratéb dòng or "standing ratéb". This generally occurs somewhat after midnight, about the first cock-crow. The sadati of party A comes forward, and his daléms ("elder brothers") stand behind him; party B continues sitting, no longer in the half-kneeling posture of one who

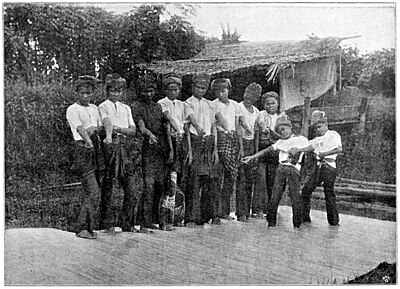

REHEARSAL OF SADATI-PLAYERS, (RATÉB DÒNG).

performs a ritual prayer, but squatting as a native always does in polite society. It sometimes happens that one party produces two or three sadatis, but the only difference in such a case is that there are two or three voices in the chorus in place of one.

The sadati (for convenience sake we adopt the singular) begins by saluting each member of the opposite party by taking the right hand between both of his and letting it slide between his palms. The others return the greeting by momentarily covering the sadati's right hand with both of theirs.

Dress of the sadati.The sadati takes up his position facing his daléms, but from time to time while speaking or reciting he shifts round so as not to keep his back continually turned to any portion of the audience. He wears on his head a kupiah or cap with a golden crown (tampōʾ), a coat with many gold buttons and trousers of costly material, but no loin-cloth. He is covered with feminine ornaments, such as anklets, bracelets, rings, a chain round the neck and a silver girdle round the waist. Over his shoulders hang a kerchief (bungkōih buraʾ) such as women are wont to wear as a covering for the head, of a red colour and embroidered with peacocks in gold thread. In one hand he holds a fan.

His dalems start him off on the first tune by chanting in chorus some nonsense words such as héhé lam heum a. This tune to which the sadati now sings is a long-drawn chant of the kind known as lagèë jareuëng[71]. The daléms chime in now and then with a refrain of meaningless words[72].

There is not much coherency in the sadati's recital; it consists of pantōns strung together of moralizings upon the pleasure and pain of love or on recent events, of anecdotes from universally known Achehnese poems (hikayats), all introduced by the superfluous request for room to be made for him (the sadati) to perform in.

Introduction of the sadati.Sadati A: Elder brothers! (here he addresses those of the opposite side) make room in order that the sadati may enter (i. e. into the space in the middle); I will give flowers to master sadati (i. e. his colleague on the opposite side), a tungkōy[73] of flowers, among which are three nosegays of jeumpa-flowers. These I shall go and buy at Keutapang Dua. The market lies up-stream, the gampōng Jeumpét down stream.—I send flowers to master sadati. Bunòt-trees in rows, a straight unindented coast, a lofty mountain with a holy tomb. There is little paper left, the ink fails; the land is at war, and my heart is perturbed[74].

During the succeeding part of the performance the daléms set the tune from time to time and chime in with their refrain, but most of these tunes, with the exception of that employed for the introduction, are lagèë bagaïh, or quick time, not slow intonations.

Continuation of the sadati's recitation.The sadati proceeds. At Chòt Sinibōng on the shore of Peulari, there is the gampōng of the mother of Meureundam Diwi. Alas! this poor little girl shut up in the drum[75], the mother of the child is dead, devoured by the geureuda-bird. Teungku Malém (i.e. Malém Diwa) climbs up into the palace and fetches the princess down from the garret.

Elder brothers, I have here a (question) in grammar, wherein I was instructed at Klibeuët at the home of Teungku Muda. I first studied the book of inflections; I began with the fourteen forms of inflection (i. e. the fourteen forms which in every tense of the verb serve to distinguish person, number and gender). What are the pronouns which appertain to the perfect tense of the verb? Tell me quickly, oh sadati (of the opposite side).

The kisah of the sidati.The above will give the reader some notion of the sort of fragmentary songs with which the sadati commences his performance. These continue for a time till a new item of the programme, the kisahs of the sadati, is reached.

Most of these kisahs consist in dialogues between the sadati and his daléms, but even where a continuous tale is recounted, the daléms take turns with their sadati in his recital.

When the daléms are speaking, the sadati always remains silent; but the intonation of the latter is invariably accompanied by the chakrum of the former; this consists in a sort of dull murmur of the sounds hélahōhō, varied by occasional clapping of the hands. Let us begin with a translation of a kisah-dialogue, which also comprises a sort of Achehnese encyclopaedia of geography and politics. We denote the sadati by the letter S and his daléms by D.

Specimen of a kisah-dialogue.Although the daléms sing in chorus and are addressed collectively by their sadati, they generally speak of themselves in the first person singular; and it is not generally apparent from what the sadati says, whether he is addressing them in the singular or the plural. We shall thus as a rule employ the singular in our translation, using the plural only in some of the many cases which admit of the possibility of its use.

Dialogue-kisah.

D. Wilt thou, oh little brother, go forth to try thy fortune and engage in trade in some place or other?