The Centennial History of Oregon, 1811–1912/Volume 1/Chapter 1

CHAPTER I

1492—1792

THE WORLD-ROUND WEST-BOUND MARCH OF MAN—WAS THE EARTH ROUND OR FLAT—THE PROPOSITION OF COLUMBUS—HOW AND WHY NAMED AMERICA—THE DREAMS OF NAVIGATORS—THE FABLED STRAIT OF ANIAN—DE FUCA's PRETENDED DISCOVERY—MALDONADO'S PRETENDED VOYAGE—LOW'W REMARKABLE MAP—VISCAINO AND AGUILAR REACH THE OREGON COAST IN 1603—CALIFORNIA AN ISLAND—CAPTAIN COOK'S VOYAGE AND DEATH—BEGINNING OF THE FUR TRADE ON THE PACIFIC—SPAIN DRIVES ENGLAND OUT OF NOOTKA SOUND AND THEN MAKES A TREATY OF JOINT OCCUPATION—GRAY DISCOVERS THE COLUMBIA RIVER.

To connect Oregon with the greatest event in the world of science and discovery—the grand achievement of Christopher Columbus—we must take a long look backward and see that the train of events set in motion by that great man never halted or turned aside from the day Columbus sighted Cat Island in the West Indies until the Oregon pioneers organized the provisional government at Champoeg. The settlement of this last and most distant portion of the United States was clearly the result of that world-wide racial impulse to move west on isothermal lines, take possession of new lands and colonize the North American continent. That impulse already in existence before the American colonies declared their independence of the Old "World, was vastly accelerated by the surrender of the British army at Yorktown.

As Columbus left no explanation of his studies of the great problem of sailing westward from Europe to find the east coast of Asia the world is left to judge him by contemporaneous events. That Columbus did ransack all possible sources of geographical knowledge in his day to get a clue to the mystery of the great western ocean there can be no doubt. It is known that he studied the works of the Greek geographer Ptolemy who wrote about 150 years after Christ. Ptolemy was the most learned man of his age; and the great problem with him and other learned men at that time was to determine the size of the inhabited world. It was the fixed belief at that age that the length of the inhabited world was not only longer than it was wide but that the length was twice that of its width. All the old Greek geographers, except Hipparchus, agreed on the proposition that the inhabited world was a vast flat plain island in the midst of a boundless ocean. Hipparchus flourished about 150 years before Christ, was the founder of the science of astronomy, calculated eclipses, discovered the precession of the equinoxes, and seeing that the heavenly bodies must be spheres concluded that the earth also was a globe. And it is a curious fact that all the calculations and speculations of those old geographers of eighteen hundred years ago continually kept pushing the coast of Asia—what we know as China and Siberia—farther and farther eastward into the supposed boundless ocean. Columbus had read and meditated on these imaginings of those ancient philosophers, and he was no doubt perfectly familiar with the tradition handed down to his age of the world that there was once a great island or continent occupying a portion of the area covered by the Atlantic ocean, but which had been by an earthquake submerged in the ocean. Plato, the most illustrious philosopher of all the ages, and Strabo, the first of geographers, both believed in the existence of such an island in the Atlantic ocean west of Europe, that had been submerged in the ocean by some mighty cataclysm of the earth. The lost island of "Atlantis" gave the name to the ocean. And this belief in an island or a continent being submerged in the ocean was not an unreasonable proposition. For there can be no uplift of the land in one place without a corresponding depression of land in some other place. And we now know from the testimony of the rocks that the area of our state of Oregon was once a part of the floor of the Pacific ocean. But what land was submerged in the ocean as our land of Oregon came up out of the ocean there is no record or tradition to tell. Columbus was familiar with all these theories and beliefs about the formation of the earth; and from them all was evolved his great proposition to sail west from Spain—and make some great discovery.

But what probably influenced his thoughts more than anything else was a little book or parchment written by the Venetian traveler, Marco Polo, in the year 1295 after his return from a long journey through the empire of Kublai Khan, what we now know as China. Polo 's published account of his travels was the great sensation and wonder of that age, was discussed by learned men all over Europe and formed the basis of many new conjectures about the size and shape of the earth. Columbus read Polo's narrative, and was familiar with all the various theories of the earth and with all the new ideas inspired by Polo's extensive travels. The great subject had taken possession of all his thoughts. And of all the learned men of that age he alone seems to have been capable of the great idea which he finally carried out. But with him it was no sudden impulse, no scintillation of genius struck out of a reckless brain. He brooded over and revolved the great concept in his mind for years. And when finally he put forth the proposition that by sailing directly westward from Europe he could reach the east coast of Asia in the latitude of Cipango (Japan) as it was then known, he was so confident and assured of the correctness of his great idea that he never hesitated or halted until he had raised his anchors and set the sails that carried him to the New World.

The only man of any note of the age of Columbus who seems to have supported him in his views was the learned Italian, Toscanelli. And on hearing of the proposition of Columbus Toscanelli wrote him a letter heartily endorsing the views of Columbus; and to demonstrate to Columbus that he could reach the east coast of Asia by sailing west from Europe, Toscanelli amended Ptolemy's map of the world to make it correspond with the description of Asia by Marco Polo, and sent the copy to Columbus. On this map the eastern coast of Asia was outlined in front of the western coasts of Africa and Europe, with a little ocean flowing between them in which he placed the imaginary island of Cipango (Japan) and Antilla.

In taking up this proposition, Columbus was met with a storm of opposition and persecution which would have crushed any other man. The church denounced the scheme as heresy, and for nearly twenty years the great man

(The greatest tribute paid to this greatest man is the following from the pen of Oregon's poet—Joaquin Miller.)

|

Behind him lay the gray Azores, |

They sailed and sailed as the winds might blow. |

|

Then, pale and worn, he kept his deck.

And peered through darkness. Ah. that night

Of all dark nights! And then a speck.

A light! A light! A light! A light!

It grew, a starlit flag unfurled!

It grew to be Time's burst of dawn.

He gained a world; he gave that world

Its grandest lesson: "On. sail on."

traveled, begged and toiled for recognition and favor from those who could give aid, and at last found a good priest who sympathized with his grand idea, and through whose influence, Queen Isabella of Spain was induced to recall a former refusal of aid.

How Columbus finally induced Queen Isabella to support his enterprise with money and two small ships, while a third ship was added by himself and friends, and how on August 3, 1492, he sailed out of Palos harbor with one hundred and twenty men in the three little ships—Santa Maria, Pinta and Nina—is an oft-told story and familiar tale. This exploratory voyage, all things considered, is the greatest enterprise ever planned and carried out by the genius and energy of a single man. The voyage itself was not a great affair, the little vessels of still less account, the use of the compass was then but little understood; the seamen were all ignorant and superstitious to the limit; but when we consider the weakness of such an outfit to venture out upon a vast and unknown ocean and brave all the terrors pictured by the imagination in addition to the real dangers of the sea, and then place over and against them all the glory and grandeur of the achievement in practically adding to the use and enjoyment of the race of man, a new world as large, useful and beautiful as the one already enjoyed, our minds are unable to grasp and no words can fully express the greatness of the achievement, or the honor, praise and obligation which mankind owes to the name of Christopher Columbus.

After seventy days' sailing westward, Columbus struck Cat Island in the West Indies. It was inhabited by red men. The people of Hindostan (India) were red. Columbus believed he had reached India—the east coast of Asia; and he called the natives Indians. The name stuck, and thus all the natives of America came to be called Indians. Columbus made three subsequent voyages from Spain to the West India islands, but never reached the mainland, and died in ignorance of his great discover}' of a continent equal to the old world and separated from it by two great oceans.

It may seem irrelevant to go back over four hundred years to begin this narrative about the state of Oregon; but it must be remembered that it was Christopher Columbus who started and steered the tide of the Caucasian race across the Atlantic which finally overran the American continent and never halted until here on the Willamette to found a state. And believing that the readers of this book will take a genuine interest in the man who discovered America, and will be glad to have a lifelike, truthful portrait of his face, we have, at much trouble and expense, procured from the Marine Museum, at Madrid, Spain, and here print the best likeness ever made of the great man.

When we look into the books of geographical discovery, we find that Oregon was for a long period of time the center of a great unknown region of myths and mystery. To see how that idea got abroad in the world, it will be necessary to go back to the opening of the Fifteenth century and follow the current of geographical exploration around the world.

The proposition of Columbus to find a short cut to Asia by sailing west from Spain was not to perish with his death. It was the good fortune of the Italian navigator, Amerieus Vespucius. who made four voyages to America and finally to discover the mainland of the continent near the equator. And like Columbus, he too returned to Spain and died poor at Seville in 1512, without knowing he had discovered a separate continent. In his letter to the King of Portugal, in whose service he had sailed to the new world, he writes July 18, 1500: "We discovered a very large country of Asia."

But the half discovered secret of all the ages was not to remain hidden from the eyes of man. Other courageous spirits followed in the wake of Columbus and Vespucius. Sebastian Cabot, an Englishman, discovered the coast of Labrador in 1497, and on a third voyage, entered Hudson's bay in 1517 before Hudson died. In 1498 Vasco de Gama, under the patronage of the king of Portugal, doubled the Cape of Good Hope and opened a new route to the Indies. This same king in 1501 sent Gasper Cortereal with two vessels to explore the northwestern ocean. In 1512 the Spanish navigator Juan Ponce de Leon discovered the Gulf of Mexico. In 1513, Vasco Nunez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama where President Taft is now digging a canal, and discovered the mighty Pacific ocean. It was a revelation second only to the discovery of Columbus. What must have been the wonder of those wandering Spaniards as they looked down from the mountain tops to the vast ocean glittering in the morning sun.

The discovery of the Pacific ocean was a great event and had been accomplished by the first land journey to the interior. It then began to dawn upon the sea-rovers that there was another ocean to be crossed to reach the riches of India. And from this discovery all the country south of the Isthmus of Panama was given up to the Spanish. And while the title to South America was thus accorded to Spain, the Spaniards did not abate one jot or tittle of their claim to North America also. And in the year 1539, Ferdinand de Soto, one of Spain's most distinguished soldiers, gathered an army of six hundred men in the Island of Cuba, and with two hundred horses and a herd of swine, sailed for the western coast of Florida, where he arrived on the 30th of May, and on landing his men, was attacked by the natives, being the first opposition made by the Indians to the occupation of the new world by the white man. From this landing point, De Soto forced his way westward against repeated attacks from the Indians until he reached and discovered the Mississippi river at the point where the north boundary line of the state of Mississippi intersects the river. Under this title of discovery, Spain held the territory down to the year 1820.

It may be supposed that on account of this activity of the Spanish in the south, the commercial and colonizing projects of the English were confined to the North Atlantic sea coast. And consequently we find Martin Frobisher, an English navigator, in 1576-8 making three voyages to America, giving his name to Frobisher 's strait, but not finding a northwest passage to Asia. Frobisher was followed by another Englishman—John Davis, in 1587-9 in three voyages, who gave his name to Davis strait. In 1570, Francis Drake, afterwards the great Sir Francis, boldly following the route of Magellan around the south end of South America, and pouncing upon the Spanish merchant vessels ladened with gold and silver from the mines of Peru, attempted to get back to England by following up the Pacific coast up past California and Oregon and going through a mythical northeast passage to the Atlantic ocean. All these navigators, and many more that we have not time to notice, were trying to find the ' ' Strait of Anian, ' which was reputed to be the short cut through North America, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans on a straight route from Europe to Asia.

How this mythical strait idea ever got possession of the minds of the

THE HOUSE—STILL STANDING—IN THE TOWN OF ST. DIE, FRANCE, WHERE THE AMERICAN CONTINENT WAS NAMED IN 1507

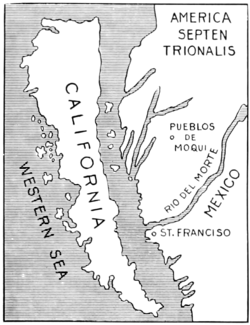

Another one of the geographical myths of that age was the belief that California was an island. A Spanish navigator by the name of Nicholas Cordoba, investigated the subject in 1615. and after exploring the Gulf of California and talking the matter over with his fellow sea captains, reported that California was in fact an island, and printed a long document describing the country as "a far extended kingdom of which the end is only known by geographical conjectures which make it an island stretching from the northwest to southeast, forming a Mediterranean sea, adjacent to the incognita contraeosta de la Florida. It is one of the richest lands in the world, with silver, gold, pearls, etc."

In 1748, one Henry Ellis, published in London, a summary of the voyages and explorations to find a northwest passage across America to China and in which he gives the story of a Dutchman sailor who having been driven to the coast of California, had found that country to be either an island or a peninsula, according as the tide was high or low. Before 1750, the Russians had crossed Asia and arrived on the coast of Bering strait, and made such discoveries as proved the existence of our Alaskan possessions, and greatly narrowed the northern mystery—they had discovered the real strait which separated America and Asia. And as embodying the geographical knowledge of this region at that time, we have printed Jeffrey's map of 1768, which shows the location of Oregon under the name of New Albion, which was the name Drake gave the Oregon coast in 1579. This is the first map to give any hint of the great river of Columbia, which is here put down on imaginary lines by both French and Russians as "River of the West."

But as time passed on and explorers and navigators converged from north to south and compared their observations, it was made plain that there was no Strait of Anian or any other navigable strait or water passage across the continent. The east coast lines had been followed from Hudson's bay south to the Straits of Magellan, and thence along the west coast north to the Bering sea, and no strait found. The result of this conclusion was, to start explorations overland, first from Canada and afterward from Missouri territory, which finally developed the emigration to Oregon. And as this fact became fixed in the minds of men, we see the then ruling powers of the world taking steps to establish claims to the country by more open and assertive action.

The first attempt to get on to the land north of California, was made by Bartolome Ferrulo, sent out in two small vessels by the Spanish government in 1543. It seems to be certain that Ferrulo did get north of 42° north latitude and near enough to the Oregon coast to obserye birds, driftwood and the outflow of a river. But he made no landing, and did not see the land on account of the fogs during the month of February. The next navigator on the Oregon coast was Francis Drake in the year 1579. Drake's claims to be the discoverer of Oregon are certainly better than those of De Fuca, and may with good reason be accepted as the fact. Drake had come around into the Pacific by way of Cape Horn, and prepared for any feat or fortune, had captured and robbed a number of Spanish merchant ships, returning from Peru and Mexico. He was to all intents, a pirate on the high seas; and knowing full well that if any Spaniard able to capture him fell in with his ship, he would get a short shrift and off the taffrail, he laid his course north close to the coast, where there were neither ships nor men, hoping to find a passage east across the continent to the Atlantic ocean; or failing in that, to cross over to Asia and get back to England by the way of Good Hope, clear of Spanish ships. In the first printed account of this voyage, it is claimed Drake reached 42° north, which would be on the southern boundary of Oregon, where it is claimed the ship got fresh water, and to get which, the ship and crew

LOW'S MAP, 1598.

DUTCH MAP

It seems necessary to state these particulars of Drake's discovery, as they throw light upon the claim the British government afterwards set up to Oregon. If Drake, on that voyage, did actually reach Oregon, then according to the international law of that period, the English had a right to Oregon from discovery. But the British government never claimed anything for Drake or that voyage. Why, Drake was at that time a pirate, and outlaw, and no rights could be founded on the acts of such. There can be but little doubt that the character of Drake's expedition was well known to the British government. After wintering at Drake's bay, Drake struck out across the Pacific ocean and reached England by way of the Cape of Good Hope route in September, 1588, after an absence of two years, being the first Englishman to sail around the earth. His return to England created a great sensation. His sailors were reported to be clothed in silks, his sails were damask, and his masts covered with cloth of gold. Queen Elizabeth hesitated long before recognizing the really great exploration of a freebooter. But finally she honored him with knighthood, and approved all his acts.

Drake was the first explorer to give a name to the country—New Albion—which may be found for the first time on the map of Honduis made in 1595.

The next exploring expedition to the Oregon coast was made by Sebastian Viscaino and Martin Aguilar, who were sent out by the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico, with two small vessels to explore the northwest coast of America. Leaving Monterey, California, in January, 1603, they .sailed northerly and falling in with bad weather were separated in a gale. The scurvy broke out on both ships, and many of the men died from the disease. But Aguilar's ship finally reached the land near Cape Blanco, Oregon, and found a river thereabouts, either Coos bay or the Coquille. Father Ascension, the chaplain of the ship, says in his account of it, that they "found a very copious and soundable river on the banks of which were very large ashes, brambles, and other trees of Castile; and wishing to enter it the current would not permit it." The same priest obtained a report from the pilot of the other ship that "having reached Cape Mendocino with most of the men sick, and it being mid-winter and the rigging cruelly cold and frozen so they could not steer the ship, the current carried her slowly towards the land, running to the Strait of Anian, which here has its entrance, and in eight days we had advanced more than one degree of latitude, reaching 43 degrees north in sight of a point named San Sebastian near which enters a river named Santa Anes." It seems to be clear that both these Spanish ship captains reached stantially the same point on the Oregon coast; and Viscaino named the point, Cabo Blanco de San Sebastian, which name has remained as the name until this day as our Cape Blanco, about half way between Coos bay and the mouth of the Rogue river.

Thus we see that in 111 years after Columbus discovered land on the east side of the continent, the coast of Oregon on the west side of the continent was clearly made out and designated by names. And these discoveries of Drake, Viscaino and Aguilar, practically closed the era of myths and mysteries so far as the sea coast was considered. For while the belief of a Strait of Anian, or some passage for ships across the continent, was for a period after that believed in or hoped for, there were no further fabricated reports of the discovery of such a passage.

And now we find a long lapse in the spirit of exploration and discovery on the northwest coast of America. Not only Spain, but all other nations practically abandoned the coast of old Oregon for nearly one hundred and seventy years. Every motive which had moved Spain to exploration in the fifteenth century was still unsatisfied. The conversion of the souls of the natives was the great proposition of the church—and the church was Spain—was still beckoning the faithful missionaries to the unpenetrated forests of the far north. The taking possession of any possible inter-oceanic ship passage grew more important as the commerce of Spain on the Pacific increased from year to year. And yet Spain failed to move again until the year 1774, only two years prior to the Declaration of Independence at Philadelphia. In that long interval of inertness, which can only be explained by Spain's surfeit of gold and plunder from Mexico and Peru, we find no more of other European powers to take advantage of the opportunity. But in 1773 the Spanish Government, moved by the reports that the Russians were not only making settlements on the east coast of Siberia, but were taking possession of the seal islands on the west coast of America, organized a strong expedition to set sail in 1774, with chaplains, missionaries to the heathen, surgeons to battle with the scurvy, and eighty men to man the ship and fight the enemies if necessary, with a year's supplies, left Monterey, California, to take possession of the whole coast of North America, north of California clear up to the point where the Russians might possibly have made an actual settlement. This expedition was under the command of Juan Perez, who proved himself an able seaman and capable commander. Perez was instructed by his government to go north to the sixtieth degree of north latitude and take possession and explore the whole coast to that extent. It seems certain from his report that he reached 55 degrees north before turning back, and at which point he had friendly intercourse and much trade with the Indians. At one time there were twenty-one canoes with over two hundred Indians around his ship with dried fish and furs to barter for knives, iron, beads and other trinkets. This expedition practically surveyed the whole coast from what is now the southern boundary of Alaska down to the California line; and as far as any rights can attach to the mere finding or discovery of new lands Perez had made good the title of Spain to the whole coast from the California line up to Alaska.

Determined to make strong the claim to the northwest coast, Spain followed up the voyage of Perez with another, the next year under the command of Bruno Heceta, with four vessels, chaplains, missionaries, one hundred and six men and supplies for a year. They left Monterey on May 21, 1775, coasted northerly and made their first landing July 14, 1775, on the coast of what is now Jefferson county in the state of Washington, about seventy-five miles south of the entrance to the Straits of Fuca. Here Heceta erected a cross and took possession of the country in the name of the king of Spain. And this was the first time European people had set foot on the coast of old Oregon, and made proclamation and record of intent to hold the land. From this point Heceta coasted southward and on August 17th, discovered a bay with strong currents and eddies indicating the mouth of a great river or strait. The place was subsequently named by the Spaniards. Ensenada de Heeeta, and which has been identified as the mouth of the Columbia river.We have now given all of the Spanish exploration of the northwest coast as is necessary to show the title by right of discovery. It must be admitted that it was a right founded wholly on the consent of other nations, who were in the same business of claiming everything in the real-estate line they could find that had not already been appropriated by others. When we consider the character of the ships those old mariners went to sea in, and braved all the dangers of the deep, it would seem that they were entitled to something better than wild land that had no appreciable value. One of the ships, not, however, entitled to be dignified as a ship (with which Heceta made that voyage along the northwest coast in 1775), was only thirty-six feet long, twelve feet wide and eight feet deep. What would the sailors of today say if asked to go upon a voyage along an uncharted coast for a year, where there was no help except from savage Indians in case of misfortune. It was just about the time Heceta and his men were beating around among the rocks of Destruction Island and fighting the Indians of Mount Olympus on the Washington coast, when General Warren and the continental militia were pouring hot shot into the British at Bunker Hill. There were fighting men and heroes in those days on both sides of America.

And now we come down to a period one hundred and ninety-nine years after Drake discovered the coast of Oregon and named it New Albion, and find George III. of England taking decisive steps to claim this country, or as much of it as was left unclaimed by the Spaniards. In 1776, the famous navigator. Captain James Cook, was dispatched to the Pacific coast with instructions to search for a passage eastwardly through North America to Europe, either by Hudson's Bay, or by the Northern sea, then recently discovered by Captain Hearne, or by the sea north of Asia; and in such search he was instructed to explore all the northwestern regions of America. His instructions were to strike the Coast of New Albion at 45 degrees north, which was supposed to be north of any discoveries then made by the Spanish. This was Cook's third and last voyage around the world, and he had left England without knowing what the Spanish navigators had accomplished before that time. And he was specially instructed "to take possession, with the consent of the natives, in the name of the king of Great Britain, of convenient situations, as you may discover, that have not already been discovered, or visited by any other European power, and to distribute among the inhabitants such things as will remain as traces and testimonials. You are also on your way thither strictly enjoined not to touch upon any part of the Spanish dominions on the western continent of America, unless driven thither by unavoidable accident, in which case you are to stay no longer than shall be absolutely necessary, and to be very careful not to give any umbrage or offense to any of the inhabitants or subjects of his Catholic majesty. And if in your further progress to the northward, as hereafter directed, you find any subjects of any European prince or state upon any part of the coast, you may think proper to visit, you are not to disturb them, or give them any just cause of offense."

Now, it is clear from these instructions that Cook was bound to respect the claims of Spain set up as prior discoveries of the Oregon coast, and the British government was bound by these instructions—Cook was to take possession of such lands as had not been discovered or visited by any other European power. He had reached the Sandwich islands in February, 1778, and sailing from the islands, came in sight of the Oregon coast on ilarch 7, 1778. He speaks of the coast as "New Albion" in his log, using the name given it by Drake nearly two hundred years before. At noon on March 7, the ship's position was 44° 33north by 236° and 30' east from Greenwich, and Cook's orders were to strike the coast at 45° north, so that he was showing good sailing qualities. The location on the Oregon coast reached first thus by Cook, is practically about the entrance of Yaquina Bay. In his log, he describes the land fairly well as of "moderate height, diversified with hill and valley, and almost everywhere covered with trees." Cook laid his course north up the coast and after passing a headland, foul weather set in and he named the point Cape Foulweather, which name has stayed with the headland to this day. Cook held to his course up the coast with continued stormy weather, until March 29, passing both the mouth of the Columbia river and the Straits of Fuca, without seeing either opening, and then turned into what he named Hope bay on the west coast of Vancouver island, and finding an extension of the bay into the land, gave it the Indian name of Nootka sound. Here he explored the country and traded with the Indians. Cook gave the names to Capes Foulweather, Perpetua and Gregory, all of which have been permanent except the last, which is now known as Arago. He traded with the same Indians as did Perez, and found silver spoons and other trinkets of European origin among them, and rightly concluded that they had been visited by more than one navigator on the coast and did not pretend to take possession of the country, although he remained at Nootka on the coast of Vancouver island for a month, making repairs on his ship.

On April 26, Cook resumed his cruise northward surveying the coast line as best he could keeping a sharp lookout for a ship passage eastwardly across the continent, for the discovery of which the British government had offered a reward of twenty thousand pounds. But he found no Strait of Anian, or any other strait; and coasted around northwesternly reaching Bering sea, and finally the coast of Asia, and after satisfying himself that there was no passage from the Pacific eastwardly to the Atlantic, he sailed for the Sandwich islands, which he reached February 8, 1779. Here he met with great trouble from the natives, and in attempting to recover a small boat they had stolen from his ship, he was violently attacked by a multitude on February 14, 1779, and brutally killed with clubs before his men could rescue him, and carried away and eaten by the cannibals. He had made three voyages of discovery around the globe, had discovered the Sandwich islands and many other lands.

Captain James Cook was the greatest of all the navigators and explorers of

CARVER'S MAP, 1778

were so highly esteemed that when Franklin was in Paris as representative of the United Colonies he was empowered to issue letters of marque against the English, but in doing so, inserted an instruction that if any of the holders of such letters should fall in with vessels commanded by Captain Cook, he was 1o be shown every respect and be permitted to pass unattacked on account of the benefits he had conferred on mankind, through his important discoveries.

Cook is described as over six feet high, thin and spare, small head, forehead broad, dark brown hair, rolled back and tied behind, nose long and straight, high cheek bones, small brown eyes, and quick and piercing, face long, chin round and full with mouth firmly set — a striking, austere face, showing his Scotch descent, and indicative of the man most remarkable for patience, resolution, perseverance and unfaltering courage.

The irony of fate which snuffed out the life of a great and good man, and deprived him of the honor and credit of opening to the world a great region filled with unexampled wealth, yet even in this last fateful voyage, gave to the commercial world a clue to vast wealth which was eagerly snapped up by citizens of four great nations. In Cook's brief stay at Nootka sound, he got in barter, a small bale of very fine furs from the Indians. These furs reached China after the death of Cook, and their extraordinary quality at once so caught the attention of all vessels trading to Canton, that the news of it spread rapidly to England, Spain, Portugal, and the United States. In consequence of this information there was a sort of gold mine stampede to the new-found El Dorado in the fur-bearing haunts of the north Pacific, which set in toward the northwest seven years after Cook had sailed away. This was the beginning of the great fur trade from which the Hudson's Bay Company made so many royal millionaires in England.

Following up this discovery of rich furs in the northwest we find Captain James Hanna, an Englishman, coming over from China in a little brig of sixty tons, with twenty men. He reached Nootka sound in August, 1785, and he had no sooner anchored his little ship than the Indians attacked him. He gave them a hot reception, drove them off, and they then obligingly turned around and offered to trade. The sea-rover accommodated them, and in exchange for a lot of cheap knives, shirts, beads and trinkets, the natives handed over five hundred and sixty sea otter skins, which would be worth at this day a quarter of a million dollars. This was the beginning of the great fur trade in old Oregon, Alaska and California.

The next navigator to visit this region after Hanna, was the famous French explorer. La Perouse, who was sent out by the French king to examine such parts of northwestern America as had not been explored by Captain Cook, to seek an inter-oceanic passage, to make observations on the country, its people and products, to obtain reliable information as to the fur trade, the extent of the Spanish settlements, the region in which furs might be taken without giving offense to Spain, and the inducements to French enterprise. But while the commander of the expedition, like Cook, lost his life on this voyage, it was in many respects one of the most valuable of all the exploring expeditions to this region. La Perou.se was accompanied by a corps of scientific observers able to report in full the value of the country, and their observations and the report of the voyage made up four volumes with a book of maps, and really gave to the world the first scientific knowledge of this vast region. The expedition had also another very decisive feature as showing at that time what other nations than England thought of the ownership of the country. La Perouse was instructed to ascertain the extent and limits of the rights of Spain, and no reference was made whatever to any rights of England, clearly showing that in the estimation of other nations, England had no rights on the Pacific coast as against Spain or any other power.

Following La Perouse in 1786, three fur-trading expeditions were dispatched to the northwest coast. One of these under the command of Captains Meares and Tipping, with the ships Nootka and Sea Otter, was fitted out in Bengal and traded with the Indians in Prince Williams sound and the Alaskan coast. A second expedition was fitted out by English merchants at Bombay, sailing under the flag of the East India Company, reached Nootka sound in June, 1786, and secured six hundred sea otter skins, not as many as they hoped for, because the Indians had promised to save their skins for Captain Hanna who had given them a thrashing, and who returned in August. This expedition from Bombay is remarkable for more than its six hundred sea otter pelts. It left behind, at his own request, the first white man to reside on the northwest coast of America — one John McKey—who being in bad health chose to take his chances with the Indians, the chief promising him protection. McKey lived for over a year with the Indians, taking a native woman for a wife, was well treated but endured many hardships, kept a journal of his experiences, and gave to the world, through Captain Barclay, who carried him away to China, the geographical fact that Vancouver island was not a part of the mainland.

The third expedition of that year was two ships fitted out in England in 1785, but did not reach the Pacific coast until 1786. It was sent out by what was called King George's Sound Company, an association of British merchants acting under licenses from the South Sea and East India monopolies, and was commanded by Nathaniel Portlock and George Dixon, both of whom had been with Cook on his last voyage. They reached the coast of Alaska in July, 1786, then drifted south intending to winter at Nootka, but from bad weather and other causes failed to find harbors and sailed to the Sandwich islands, where they wintered. They returned to the coast in 1787, and repeated their cruise of drifting southward from Alaska. Portlock and Dixon named several points on the coast on this cruise, secured two thousand five hundred and fifty sea otter skins which they sold in China for $54,857, while the whole number of otter pelts secured by the other fur traders—Hanna, Strange, Meares and Barclay down to the end of 1787 was only 2,481 skins. Captain Barclay reached the coast at Nootka in June, 1787, coming out as a commander of the ship Imperial Eagle, which sailed from the Belgian port of Ostend under the flag of the Austrian East India Company, making another nation engaging in the fur trade. Barclay went no further north than Nootka, got eight hundred otter skins and then sailed southward, discovering Barclay sound; continuing his voyage south, passing the Strait of Fuca without seeing it, he sent off a boat to enter a river, probably the Quillayute, with five men and a boatswain's mate, where they were attacked by the Indians and all killed. These were probably the same savages that gave Heceta and his men such a battle in 1775. Mrs. Barclay had accompanied

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK.

Greatest of English Navigators

And to this Yankee skipper from Boston, the American, Robert Gray, more honors came in the exploration of the northwest than to any other man. He was not only the first to sail a ship through the Straits of Fuca—the discoverer of the Columbia river—but he was the first American to circumnavigate the globe under the national flag, which he did in 1790, by the way of Good Hope, trading his furs to the Chinese at Canton for a cargo of tea.

Here our record of the explorations of the northwest from the seacoast comes to a close. We have given enough to enable the reader to follow the story and see how these explorations gradually concentrated to. the point of discovering the river which drains the empire of old Oregon. The foundation of our title to the whole northwest, clear up to the Alaskan boundary, and the diplomacy in settling that title will be better understood when reading future chapters after having read this chapter through.

We may pause here for a moment and contemplate the mischances of great men—the greatest of men. While the world has accorded to Christopher Columbus the imperishable fame and honor of discovering the American continent, there can be no doubt but that other European mariners had touched on the continent of America before him. There is no doubt that the Scandinavians under the lead of Leif Ericson had crossed over to the western hemisphere more than a hundred years before Columbus was born. But they left no settlement, and made but little if any record or comment of the matter. It was a matter of no importance to them, and no one ever followed up their lead. It is conjectured that Columbus had heard of this discovery from the Icelanders whom he visited fifteen years before he sailed away from Palos into the unknown western ocean. But if so, Columbus never mentioned the fact, and there is no evidence that he had ever heard of the Scandinavian discovery.

Columbus was rightly entitled to name the land he had discovered, although he had never reached the main land, but had only set up his banner on a neighboring island. But sentiment, poetry and praise alike has for four hundred years striven to undo the great wrong to the greatest hero. The ship that first entered Oregon's great river bore his name; and the mighty river itself is a perpetual memorial to the honor of Christopher Columbus.

To Americus Vespucius, who was born at Florence, Italy, on the 9th of March, 1451. was given the honor of naming the New World. Vespucius moved from Italy to Spain in the j'ear of 1490, and made the acquaintance of Columbus before he sailed from Palos. And on the return of Columbus to Spain with the great discovery Vespucius was one of the first to greet the great discoverer. But he (Vespucius), then a merchant at Seville, made no effort to verify the report of Columbus until 1499. when he accompanied Ojeda on his expedition to America as an astronomer. Vespucius made four voyages to the New World, but he had not the chief command of these expeditions; and like Columbus died without knowing he had reached a separate continent. In a letter to the King of Portugal, in whose services he had sailed, July 18, 1500, he says: "We discovered a very large country of Asia." And, like Columbus, after giving to the world all the riches of America, he died a poor man. passing away at Seville in 1512.

But how came Vespucius to receive the great honor of naming the New World? The answer is: Vespueius wrote a book—an account of his voyages. If Columbus ever wrote any report of his discovery voyage, it was buried under the envy and malice that finally destroyed him, and was not given to the world at that time.

The reader must now go with the historian to a little school at the little old town of St. Die at the foot of the Vosgian Alps mountains in France. In the year 1507 this school was in the hands of some pious monks, as were all schools in those days. The over-lord of this institution was Rene II., Duke of Lorraine; who on one of his Ducal visits to the little school carried with him, being a patron of arts and sciences, a Mss. book of French, which he had then recently received from Italy, entitled "Quatre Navigations d'Amerique Vespuce." But whether Vespueius was the author of this book or not, there is no account. That incident took place thirty-nine years after the death of Gutenberg, the inventor of printing. At that date the monks and governors of the little school had just purchased and set up the first printing press in that part of France; and were at that time preparing to print a geography of the world, and which they entitled a ' ' Cosmography. ' ' Here then was a grand chance for the new book—a piece of up-todate geography; and so the manuscript brought by the Duke must go into the new book. And it went in under the title

"THE LAND OF AMERICA"

and the introduction to it on page 30 of the book reads: "There is a fourth quarter of the world which America Vespuci has discovered, and which for this reason we call 'America, the land of Americ' "And further along the book says: "We do not see why the name of the man of genius, Americo, who has discovered them, should not be given to these lands—the more so as Asia and Eiirope bear the names of women." Alack! and alas! The mighty deeds of the great Columbus overlooked or forgotten within a year after his poor body was laid in the grave! And this was the New World, named by the French who had not then sent out a single voyage of discovery; and who by that book and printing press were successful in giving to a man whose work had not been conspicuous, the name which rightly belonged to the great Columbus. On another page is given the pictiire of the building, yet standing, where America got its name.