The Czechoslovak Review/Volume 3/Events in Bohemia

THE CZECHOSLOVAK REVIEW | ||

Jaroslav F. Smetanka, Editor. | ||

| Vol. III, No. 2. | FEBRUARY, 1919 | 15 cents a Copy |

Events in Bohemia

West of the Rhine and north of Italy everything is in a state of chaos. Only the Czechoslovak Republic stands firmly in the very heart of Europe as an island of order and an outpost of the Allies. Its complete isolation from all friends is the principal complaint voiced by the Czechoslovaks who are trying to make the best of a difficult situation. It takes four days for a telegram to go from Prague to Paris and letters are forwarded only upon special occasion and as a special favor. Badly needed supplies which the Western Powers are ready to sell can not be forwarded, and when the Czechoslovak delegates to the peace conference, premier Karel Kramář, and foreign minister Edward Beneš desire to communicate with their governmentthey are obliged to send a courier in a round about way, through Italy, Jugoslavia and German Austria. Even the wireless service between Prague and Paris is maliciously interfered with by the great German wireless station of Nauen.

All this emphasizes the soudness of a plan which has long been advocated by Czechoslovak and Jugo-Slav statesmen, namely to create a corridor running along the western boundary of Hungary and connecting Jugoslav territory with Czechoslovakia. This zone which would be about 100 miles long covers a territory which is settled by a racially mixed population; the strongest element in it are the Germans, but there are also both Magyar, and Jugoslav and Slovak minorities. If the peace conference decided to create this corridor, it would mean the inclusion of some 200,000 Germans and 100,000 Magyars in Slav territory, but it would give twelve million Czechoslovak citizens access to the sea through friendly territory and it would separate permanently eight million Magyars from their German friends. If there is a case, where the wishes of a small number of local population must yield to higher strategic and economic considerations, surely the plan for a corridor to connect the Czechoslovaks with the Jugoslavs should commend itself to Allied statesmen.

Notwithstanding their difficult position the Czechoslovaks are trying to put their state in order and repair the ravages of the war. Masaryk’s great reception in Prague on December 21 and 22 was in a manner of speaking the closing act of those two great months since the overthrow of Austrian rule.

Accounts of Masaryk’s welcome given in Czech papers make one feel that December 21st, 1918, was the greatest day in twelve hundred years of Prague’s history. In addition to half a million people living in Prague who lined up the streets through which Masaryk passed on the way from the station to the castle of Hradčany there were half a million visitors in Prague. Out of several speeches made by representatives of the people on this occasion one may quote a few sentences from the address of welcome pronounced by Alois Jirásek, the greatest living Czech novelist: “You left your country at the time of its greatest slavery. Now you return to a free state as its first president. You left Prague alone, now you return at the head of noble companies of Czechoslovak warriors who bring moral and material help to our young republic. Our age-long enemy is vanquished; the terrible fight of two worlds is ended in a victory of justice and humanity, of which you have ever been a herald and defender by word and pen. We have lived to see our deepest desires fulfilled, the government of our country has been returned to us. For centuries there have been no such glorious moments in the life of our nation, unless perhaps when George Poděbrad was elected king,’ when many wept for joy, because they were freed of subjection to Ger- man kings.’ Blessed was, Mr. President, your work which will be an epoch in our history, blessed shall be our nation. Welcome to you, our hero and victor, whose name generations upon generations shall called blessed.”

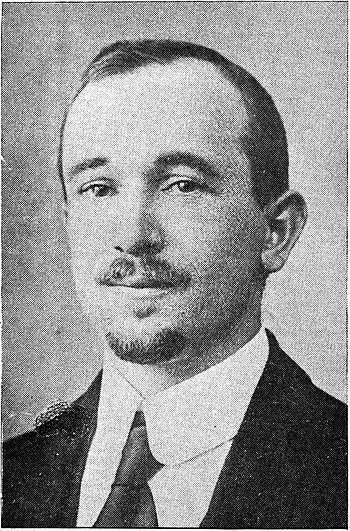

KAREL KRAMÁŘ.

Czechoslovak Premier, Delegate to Peace Conference.

President Masaryk’s arrival was expected with many secret hopes by the Germans of Bohemia. They looked upon him in somewhat the same light as upon Wilson; they believed him to be an idealist who could be easily deceived by protestations of innocence and appeals to high sounding principles. The Germans were disappointed in Masaryk, as they had been disappointed in Wilson. In his first presidential message Masaryk assured the German speaking citizens of the Czechoslovak Republic that they would have full civic rights, full opportunity to carry on their distinctive national life and that a wide scheme of local self-government would satisty all their just demands; but on the question of yielding to the separatist movement and conceding their desire to join Germany Masaryk was as firm as the rest of his countrymen. No concession is possible in the matter of cutting up the national boundaries of Bohemia and leaving to the tender mercies of the Germans several hundred thousand Czechs in northern Bohemia. The whole question has lost its practical and urgent character, as all the districts claimed by the Germans have submitted to the rule of the Prague government. The so-called government of German Bohemia was compelled to abandon its headquarters in Liberec; it fled first to Saxony and then to Vienna. Now only Rudolf Lodgmann, styling himself president of the provincial government of German Bohemia, sends out from his safe retreat in Vienna complaints against fhe rapacity of the Czechs who would not give up to the Germans one-third of their territory.

After the Allied army representatives in Budapest notified Count Karolyi to withdraw Magyar troops from Slovakia as delimited by them, Czechoslovaks troops under the command of Italian General Luigi Giuseppe Piccione occupied all this territory without further armed conflict. The city of Prespurk for which the Magyars have made a most determined struggle came also into their hands and is sure to remain in Czechoslovakia as its great Danube port and the second capital of the republic. Thus the two principal difficulties with which the new republic had to deal, taking possession of territory claimed by Germans and Magyars, were happily solved. But in the meantime a complication that seemed at first of slight importance grew into larger dimensions.

EDWARD BENEŠ.

Czechoslovak Foreign Minister, Delegate to Peace Conference.

Two days after the national committee in Prague carried out the succesful revolution against Austria, Polish soldiers from Cracow took possession of coal mines in Austrian Silesian territory which had never belonged to Poland and had been always a part of the Bohemian crown, but which has a considerable Polish element among its workingmen. Now the relations between the Czechs and the Poles, both Slav peoples and both threatened by Germans, had always been friendly, and while the Czechs deprecated the unseemly haste of the Poles in taking possession of disputed territory, they did not want to use armed force and aggravate the original cause of the quarrel. A peaceful course appeared the more commendable, because it was ascertained that the forcible occupation of the coal district was undertaken by orders of Polish authorities in Cracow, while on the other hand the principal Polish government at Warsaw was willing to negotiate with the Czechs about the disposition of the district and the Polish National Council of German Poland sent a delegation to Prague to congratulate the Czechoslovaks on the winning of independence and to express a hope for close alliance.

But in the meantime the disruption of public life in Polish territory and the strong taint of Bolshevism among certain classes of Polish workingmen brought about an almost total suspension of coal production, and as a result of it great steel mills in the neighboring Czech districts and the whole of Slovakia and even Magyar territory were deprived of necessary coal. At the same time Bolshevist agitators found their way into Moravia from the Silesian coal mines seized by the Poles. Finally at the end of January the district was taken possession of by Czech troops to be held for final disposition by the peace conference.

In internal matters the peaceful and orderly development went on. Czech talent for public administrition showed itself in the smooth working of the old Austrian governmental machinery under the sovereingty of the new republic. Taxes continued to be paid and in fact were paid far more promptly than under the imperial regime. The eight-hour working day was enacted as the standard, but workingmen and especially coal miners voluntarily worked longer hours in order that production might be increased and that the new state might have merchandise with which to buy needed supplies and set its financial housekeeping on a safe foundation. The greatest financial problem is the introduction of new currency in place of the depreciated Austrian financial medium. The reports of the Austro-Hungarian Bank indicate a total circulation of 34 billion crowns, but the real amount is 46 billion. The gold reserve back of this immense mass of paper is insignificant, and as a result the value of the crown which before the war was a fraction over 20 cents is now only about 6 cents. It is simply impossible for the Czechoslovak Republic to purchase its needs abroad and pay a three-fold price in depreciated Austrian currency. But until the boundaries of the new republic are permanently settled, the Austrian paper crown must remain the circulating medium of Czechoslovakia. A number of sharp conflicts between Prague and Vienna were caused by the reckless acts of the amateur statesmen of German Austria who on the one hand kept working the press of the Austro-Hungarian bank so as to produce a few more billion crowns and on the other hand kept selling the immense supplies of the dissolved Austrian army at ridiculous prices. To evolve order out of the bankrupcty of the Dual Monarchy will be a terrific task.

The Czechoslovaks hope that the peace conference will hurry its labors and that at least the preliminary peace will be signed early in Spring. Until then the position of the republic will remain difficult and irregular. So far only the French and the British have accredited their ministers to the Prague government and neutral countries like Switzerland have not as yet extended their recognition. Nor has America sent a diplomatic representative to Prague.

![]()

This work was published before January 1, 1929 and is anonymous or pseudonymous due to unknown authorship. It is in the public domain in the United States as well as countries and areas where the copyright terms of anonymous or pseudonymous works are 95 years or less since publication.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse