The Czechoslovak Review/Volume 3/The Saviors of Russia

The Saviors of Russia

By Kenneth Miller.

All along the Volga valley, on across the heights of the Ural Mountains, across the broad steppes of Siberia to the Baikal district, across Manchuria and the Amur district as far as the Pacific Ocean at Vladivostok, there has been heard during the summer that is past the cry: ‘The Czecho-Slovaks are coming!’

It has been a cry of relief, like unto the glad some shouts of prisoners released from captivity, for the coming of the Czecho-Slovaks has meant for the milions of people in Siberia and Eastern Russia liberation from the tyrannical rule of the Bolsheviks, the restoration of a government by al the people, the downfall of a government by one class for its own selfish interests.

When the Czecho-Slovaks first began their military operations against the Bolsheviks in the latter part of May, there was considerable confusion upon the part of the man in the street as to the meaning of it all. For although the Czecho-Slovaks are Slavs like the Russians, and although this particular army had formed an integral part of the Russian army and had rendered invaluable service to the Russian forces, the people as a whole had no very clear idea as to who they were, what they wanted, where they were going, and why they had declared war upon the Bolsheviks. Acustomed as they were after the turbulent events of the past year to insurrections and civil strife—to conflicts betwen Ukrainians and Bolsheviks, to Dutoff’s and Korniloff’s warfare against the Soviets, they looked upon this new conflict as but a new and rather strange element in the general disorder. Things could not be any worse than they are now, let the Czechs come and have their way, it is all the same to us. Such was the attitude of the average man at the time.

Then there began to be spread abroad more definite news as to who the Czecho-Slovaks were and what they wanted. The people learned that they were mostly former prisoners of war who had enlisted in the ranks of the Russian army to fight against Austria in the hope that they might thereby gain the freedom of their home-land, Bohemia. After the Brest-Litovsk peace they had concluded that Russia was no place for an army that wanted to fight against the Central Powers, and had started do depart for the French front by way of Siberia and Vladivostok. Trotsky and his colleagues, however, under suasion of the German ambassador,, decided that it would be better to have them join his Red Army, and when they refused to do so, ordered their complete disarmament. Rather than submit to such ignominious treatment the Czecho-Slovaks decided to beat their way through to Vladivostok by force.

Right on the heels of these reports came the Czecho-Slovaks themselves. They were uniformed like the soldiers of the old Russian army, save for the little red and white ribbon that they wore in their hats. But what a contrast they presented to the “Tovarishi” of the disintegrated Russian army and to the bandits of the Red Army! Clean-cut, straight-forward looking fellows, honest and courteous in their treatment of the civilian population, with such order and discipline in their ranks as the Bolshevik-ridden Russians had not seen in many months, they immediately won the favor and soon the affection of all the people with whom they came in contact.

And before the astounded people could realize what was going on, and before the bewildered Bolsheviks could gather their wits together, the Czechs had gained control of all the main points along the trans-Siberian line from Samara as far as Irkutsk, and had disarmed or scattered to the four winds the Bolshevik and Internationalist (Magyar and German prisoners) forces.

At first the Czecho-Slovaks announced that they were not aiming at any interference in the internal affairs of Russia, but were only assuring their safe passage throught to Vladivostok, to which point they were to proceed as soon as practicable. But what the Bolsheviks are pleased to call the “dark forces of counter-revolution”, or in short those who believed in a different kind of democracy than that of the Soviets, saw immediately that here was a golden opportunity to overthrow the Bolshevik tyranny, and establish a new government making for a truce democracy. An organization for this purpose had long since secretly existed throughout Siberia in the temporary Siberian Government, and the leaders of this organization had been but waiting for a favorable opportunity to bring about a coup-d’-etat. They rightly judged that no more favorable opportunity could be found than that afforded by the Czecho-Slovak movement, when the Bolsheviks had no arms with which to continue their terrorization of the people. The leaders of the Czecho-Slovaks were consulted, and, since the Bolsheviks would not allow them to depart, were persuaded to join in this attempt to free Siberia for ever of the Bolshevik yoke.

New local governments were established, those in Siberia centring around the Siberian government at Omsk, and those in Russia around temporary committees formed principally of members-elect to the Constitutional Assembly that the Bolsheviks disbanded in November 1917 because there was not a majority of Bolsheviks.

The people were enraptured over their sudden good fortune, and could not say too much of their gratitude to their deliverers, the Czecho-Slovaks. The newspapers were filled with articles and poems singing their praises, huge demonstrations were made in the cities they had freed from Bolsheviks rule. “Now we have shaken off the Bolsheviks here in Siberia, and we shall soon break their rule in European Russia; we shall establish a new government based on the decision of a popularly-elected Constitutional Assembly, we shall re-organize the Russian army, and with the help of the Allies establish anew the Eastern front against the Central powers and fight until every inch of Russian territory is freed from German influence.” This was the sincere and decided resolve made not only by the spokes man of the new governmental organizations, but by the common citizen. Feeling ran high, and the future at last began to look bright and rosy, after many months of darkness and despair. It seemed as if Russia were about to be saved; saved from the Bolsheviks, saved from the Germans, saved for the Russians. And the Czecho-Slovaks were the saviors. They were the heroes of the country.

But the Czecho-Slovaks were not deceived by their early victories into thinking that all was going to be plain sailing for them. If their decision to support the counter-Bolshevik forces and to make their battle their own was made quickly, it was nuot made without counting the cost. They were on the ground and were in a position to judge the Russian situation as no other non-Russian people, owing to their intimate knowledge of Russian affairs and the Russian people. They were cut off from the outside world, and could not consult with their supreme authority, the Czecho Slovak National Council, nor with the Allies. They were fully aware of the responsibility they took upon themselves, but were convinced that Professor Masaryk, their leader, and the Allies as well, would support them in their action, when all the facts were known. They began the battle for their own self-protection, but they continued it for the restoration of Russia to the Russian people, believing that thus they would be rendering a greater service to the Allied cause than they would by proceeding to the French front, as they had originally planned. But in spite of their confidence that they had taken the only course possible ,they were all greatly relieved and delighted when word came through from the Allied ambassadors at Vologda to the effect that the Allies thanked the Czechs for what they had done in Russia and Siberia, approved of their course of action and were beginning armed intervention in Russia and Siberia in the end of June.

From that time on the Czechs set to work to prepare the ground for the coming of Allied troops, the re-organization of the Russian Army, and the re-establishment of an Eastern front against the Germans, with whom the Bolsheviks were more and more openly allying themselves. Their first task was to open the way to the east so as to join forces with their comrades who had already reached Vladivostok and with any allied troops that might be there.

Neither the Czechs nor the Allies at Vladivostok expected that it would be possible for connection to be made with the main body of the Czech troops in Siberia and the Ural District before Spring. But the Czechs did many unexpected and unheard of things in the course of their campaign, and the utter amazement of all the authorities in Vladivostok and eastern Siberia General Gaida with his small force of Czechs and Russians succeeded in making connection with the Cossacks and Czechs operating in Manchuria in the early days of September.

General Gaida’s campaign across the steppes of Siberia and through the Lake Baikal region was one of the most brilliant achievments of the summer. Having at his disposal only a regiment and a half of Czech troops and a few raw Siberian troops, Gaida sent them scurrying along the railway lines againt one place after another, delivering one unexpected and telling blow after WITH THE CZECHOSLOVAK FIGHTERS IN SIBERIA.

A quick firing gun captured at Penza.

Czechoslovak railroad car. another until all the important points along the Siberian line had fallen before him, and his men stood at the gates of the city of Irkutsk. Tomsk, Novo Nikolaevsk and Krasnoyarsk fell in succession. In the early stages Gaida never sent more than a battalion against a city of twenty-five thousand inhabitants;

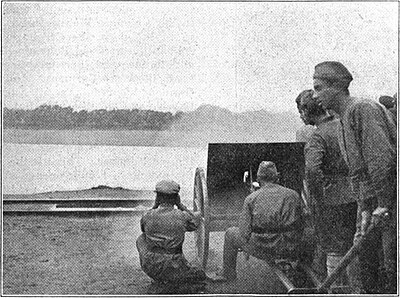

Crossing the river Tobol.

Working a quick firing gun at Ufa. he relied upon surprise attacks, terrifying bomb throwing, and a considerable sprinkling of good old American bluff to put to rout the disorganized “Reds”; and he never had even a set-back.

The Bolsheviks retired beyond Irkutsk, abandoning that city without a battle, evidently counting upon making a final stand at the Baikal where the tunnels, the lake and the mountains offered splendid natural advantages for a defending army. But Gaida at one time sent forces some two hundred versts around on foot and surprised the Bolsheviks in the rear, at another time he despatched men across the lake to fall upon the Bolshevik rear, while upon still another occasion he deceived the enemy by means of false dispatches into believing that he was obliged to retire, and then laid an ambush for them, and nearly cut their forces to pieces. This sort of warfare was too brainly altogether for the simple Bolsheviks, and Gaida soon had them making eastward as fast as they could into the very hands of the Czech, Cossack and Allied forces advancing from Vladivostok.

In the meantime the Czechs in the Ural District, after taking the important Bolshevik centre at Ekaterinburg, found themselves faced with forces that were giving increasing evidence of German organization and officering. They did succeed in capturing the city of Kazan and making away with seven hundred and fifty millions of gold that the Bolsheviks had intended to turn over to Germany.

Grave of John Klecanda, Secretary of the Russian Branch of the Czechoslovak National Council, buried at Omsk. But, after that, the superior forces of the enemy and the lack of fresh troops to relieve them and the unreliability of the raw Russian troops forced them to withdraw step by step. They were purposely maintaining the Volga front with the important cities of Samara and Orenburg against the coming of the Allies, but when weeks went by and the Allies gave no sign of coming to their help, they decided to withdraw from the entire region around the Volga and establish such a front as they could themselves hold without the help of the Allies.

From a military stand-point the outlook along the Urals is far from bright. To be sure, the entire Czech Army Corps numbering about eighty thousand men is now united, and with the fresh troops that have arrived from the East it is expected that Perm will be taken, and a new and shorter front established from that city south to Ufa. But even that front cannot be held very long by the Czechs alone, as they now have about two-hundred and fifty thousand well-organized troops against them. The new Russian army will be of little help without months of training, and the Allies are not to be seen.

The Czecho-Slovaks have in the meantime gained the recognition of the independence of their home-land, and now look forward to returning to a free Bohemia. The Allies have given them splendid diplomatic and political support, and have made fair promises of military support to the Czechs without number. But the only Allies that the Czechs have seen to date are a few official governmental and military agents.

The Czecho-Slovaks have made Siberia and one of the wealthiest regions of Russia “safe for democracy”. No one denies that there are great political and technical obstacles in the way of an armed Allied expedition into western Siberia; but also no one who knows the situation here, who has seen it with his own eyes, will deny that now is the golden opportunity to save Russia and set her on her feet; no one will deny that the Czechs have rendered an incalculable service to the cause of democracy, and that their victory so dearly won, stands in imminent danger of being brought to nought.

In Bohemia there is a fable. And in this fable there is a mountain—the mountain Blanik. And in the mountain Blanik, in the hollow middle of it, in the dark, the Czechoslovak army stands. And to the north of Bohemia there are Germans, and to the west there are Germans, and to the south there are Germans. And age after age the Germans triumph. Age after age they destroy the Czechs and the Slovaks. But age after age the Czecho-Slovak army still stands in the mountain Blanik, in dream, in readiness. And a moment comes. It is the moment of moments. There is the most danger. There is the most chance. And the mountain Blanik opens; and the Czecho-Slovak army marches out, ready to the moment, armed to the moment, soldiers, commanders, all; and Bohemia lives.

So speaks the fable. But where is the mountain Blanik? In the fable it is in Bohemia. In fact it turns out to be in Bachmach in Russia, and in Irkutsk in Siberia, and in Vladivostok on the shore of the Pacific.

Don’t be deceived ; the brains of that Slav race, that great race which extends all the way through Siberia, are to be found neither in Moscow, nor at Petrograd. nor at Belgrade, nor at Sophia, but at Prague. From this city went forth all the regenerators of the Slav race. In a war of intellectual trenches, so to say, they won with a wonderful tenacity triumphs on triumphs.Louis Leger.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1929.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1968, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 55 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse