The History of the Standard Oil Company/Volume 2/Chapter 16

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

THE PRICE OF OIL

IT is quite possible that in keeping the attention fixed so long on Mr. Rockefeller's oil campaign the reader has forgotten the reason why it was undertaken. The reason was made clear enough at the start by Mr. Rockefeller himself. He and his colleagues went into their first venture, the South Improvement Company, not simply because it was a quick and effective way of putting everybody but themselves out of the refining business, but because, everybody but themselves being put out, they could control the output of oil and put up its price. "There is no man in this country who would not quietly and calmly say that we ought to have a better price for these goods," the secretary of the South Improvement Company told the Congressional Committee which examined him when it objected to a combination for raising prices.

Four years after the failure of the first great scheme, a similar one went into effect. What was its object? J. J. Vandergrift, one of the directors of the Standard Oil Company at that time, questioned once under oath as to what they meant to do, said: "Simply to hold up the price of oil—to get all we can for it." Nobody pretended anything else at the time. "The refiners and shippers who are in the association intend there shall be no competition." "It is a struggle for a margin." "The scope of the association is an attempt to control the refining of oil, with the ultimate purpose of advancing its price and reaping a rich harvest in profits." These are some of the comments of the contemporary press. The published interviews with the leaders confirm these opinions. Mr. Rockefeller, always discreet in his remarks, denied that the scheme was to make a "corner" in oil; it was "to protect the oil capital against speculation and to regulate prices." H. H. Rogers was more explicit: "The price of oil to-day is fifteen cents per gallon" (March, 1875). "The proposed allotment of business would probably advance the price to twenty cents… Oil to yield a fair profit should be sold for twenty-five cents per gallon."

What was the exact status of this refining business out of which it was necessary to make more in the year 1871, when the first scheme to control it was hatched? The simplest and safest way to study this question is by means of the chart of prices on pages 194 and 195.[1] On this chart the line A shows the variation in the average monthly price, per gallon, of export oil in barrels in New York from 1866 to June 1, 1904. The line B shows the average monthly price, per gallon, of crude oil in bulk at the wells. A glance at the chart

CHART SHOWING PRICE OF OIL FROM 1866 TO 1904.

The above chart is adapted from one published in the Report of the Industrial Commission, Volume 1, 1900, and is brought up to date. The figures at The figures at the right and left stand for the price per gallon in cents. The dates are placed at the top. The figures on which the export and crude lines are based are those taken from the "Oil City Derrick Hand-Book." Those on which the water-white line is based are from the Oil, Paint and Drug Reporter.

A shows the variations in the price per gallon of refined oil for export in barrels in New York. The price of barrels varies slightly, but is usually estimated at 2½ cents per gallon.

B shows the variations in the price per gallon of crude oil in bulk at the wells.

C shows the variations in the price per gallon of water-white oil (150º test) in barrels in New York. This is the usual domestic oil.

The margin or difference between the price of crude and refined is easily calculated. Thus at the end of 1876 the crude line shows the price of crude to be about nine cents—the price of refined about twenty-nine; the margin was therefore twenty cents.

will show the difference or margin between the two prices. It is out of this difference that the refiner must pay the cost of transporting, manufacturing, barrelling and marketing his product, and get his profits. Now in 1866, the year after Mr. Rockefeller first went into business, he had, as this chart shows, an average annual difference of 35 cents a gallon between what he paid for his oil and what he sold it for. In 1867 he had from 26½ to 20 cents; in 1868, from 20 to 22½; in 1869, from 21 to 18; in 1870, from 20 to 15.[2]

There were many reasons why this margin fell so enormously in these years. All of the refiners' expenses had rapidly decreased. In 1866 but two railroads came into the oil country; by 1872 there were four connections, and freights fell in consequence. In 1866 carrying oil from the wells by pipelines was first practised with success, by 1872 all oil was gathered by pipes, thus saving the tedious and expensive operations of teaming. Tank-cars for carrying crude oil in bulk had replaced barrels and rack-cars. The iron tank, holding 20,000 barrels, was used instead of the wooden tank holding 1,000 barrels. On every side there had been economies, and because of them the margin had fallen. But not only were the expenses coming down; so were the profits. The money which had been made in refining oil had led to a rapid multiplication of refineries at all the centres. In 1872 there was a daily refining capacity of about 46,000 barrels in the country, and the daily consumption of that year had been but 15,000 barrels. This large capacity produced the liveliest competition in selling, and every year the margin of profit grew smaller.

Now it is natural that men should struggle to keep up a profit. The refiners had become accustomed to making from twenty-five per cent. to fifty per cent. and even more, on every gallon of oil they put out. They had the same extravagant notion of what they should make as the oil producers of those early days had. No oil producer thought in the sixties that he was succeeding if his wells did not pay for themselves in six months! And as their new industry slowly but surely came under the laws of trade, increased its production, was subjected to severe competition, as they saw themselves, in order to sustain their business, forced to practise economies and to accept smaller profits, they loudly complained. There was never a set of men who found it harder to accept the limitations of economic laws than the oil producers of Pennsylvania. The oil refiners showed the same dislike of the harness, and in 1871, as we have seen, Mr. Rockefeller and a few of his friends combined to throw it off. What they proposed to do was simply to get all the refineries of the country under their control, and thereafter make only so much oil as they could sell at their own interpretation of a paying price.

There was not enough profit in the margin of 1871. Now what was the profit? According to the best figures accessible of the cost of oil refining at that day, the man who sold a gallon of oil at 24¼ cents (the average official price for that year) made a profit of not less than 1¼ cents—52½ cents a barrel.[3] Josiah Lombard, a large independent refiner of New York City, when questioned by the Congressional Committee which, in 1872, looked into Mr. Rockefeller's scheme for making oil dearer, said that his concern was making money on this margin. "We could ship oil and do very well." A. H. Tack told the Congressional Committee of 1888, which was trying to find out why he had been obliged to go out of the refining business in 1873, that he could have made twelve per cent. on his capital with a profit of ten cents a barrel. Scofield, Shurmer and Teagle, of Cleveland, made a profit of thirty-four cents a barrel in 1875, and cleared $40,000 on an investment of $65,000. Fifty-two cents a barrel profit then was certainly not to be despised. The South Improvement Company gentlemen were not modest in the matter of profits, however, and they launched the scheme whose basic principles have figured so largely in the development of the Standard Oil Trust.

The success which Mr. Rockefeller had in getting the refiners of the country under his control, and the methods he took to do it, we have traced. It will be remembered that for a brief period in 1872 and 1873 he held together an association pledged to curtail the output of oil, but that in July, 1873, it went to pieces.[4] It will be recalled that three years after, in 1875, he put a second association into operation, which in a year claimed a control of ninety per cent. of the refining power of the country, and in less than four years controlled ninety-five per cent.[5] This large percentage Mr. Rockefeller has not been able to keep, but from 1879 to the present day there has not been a time when he has not controlled over eighty per cent, of the oil manufacturing of the country. To-day he controls about eighty-three per cent.

Now it is generally conceded that the man or men who control over seventy per cent. of a commodity control its price—within limits, very strict limits, too, such is the force of economic laws. In the case of the Standard Oil Company the control is so complete that the price of oil, both crude and refined, is actually issued from its headquarters.

Now, with the help of the chart, let us see what Mr. Rockefeller and his colleagues have been able to do from 1872 to 1904 with their power over the price of oil. The first association which worked was brought about late in 1872. What happened? Prices for refined oil were run up from 23 cents a gallon in June to 27 cents a gallon in November, and the margin increased from 13.6 cents to 17.7 cents. From a profit of about 1½ cents a gallon they rose to one of over 4 cents. Unfortunately, however, the refiners of that period were not educated to the self-restraint necessary to carry out this scheme. They very soon failed to keep down their output of oil and overstocked the market, and the whole machine went to pieces. Mr. Rockefeller had been able to make oil dear for a short time, but only for a short time. Worse than that, what he had been able to do brought severe public condemnation. It had, indeed, produced exactly the result the economists tell us too high prices must produce—limitation of the market and stimulation of competition in rival goods. Mr. Rockefeller's second scheme to work out the good of the oil business by making oil dear resulted in decreasing oil exports for the first time since the discovery of oil.[6] It also increased one of the chief grievances of the American refinery—that was, the exporting of the crude oil to be refined in Europe. Where the exports of crude had been something over eleven million gallons in 1871, they were now over sixteen millions. And it set the shale-oil factories of Scotland to work merrily. It was cheaper for Great Britain to use oil from Scottish shales than to buy oil sold under Mr. Rockefeller's great plan for benefiting the oil business. So for the time the scheme fell down.

As the diagram shows, the margin dropped rapidly back after this brief success from eighteen to thirteen cents, nor did it stay there. With the return of competition, in the fall of 1873, it continued to drop rapidly. By the end of the year

it was down to eleven cents; by the end of 1874 to nine. What had done it? A decline in expenses, coming from the multiplication of pipe-lines, reduction in freight charges, and free competition in the markets. Nothing else.

In spite of the obvious economic effects of his scheme in 1872 Mr. Rockefeller did not give up his theory that to make oil dear was for the good of the business. He went steadily ahead, developing quietly his plan of a union of all refiners, pledged to limit their output of oil to an allotment he should assign, to accept the freight rates he should arrange for, to buy and sell at the prices he set. It was a year before the alliance was nearly enough complete to make its power felt. By the summer of 1876 it claimed to have nine-tenths of the refiners in the country in line. At that time a situation rose in the crude oil market well calculated to help it in its intention to raise prices. This was a falling off in the production of crude oil. An advance in its price had come in the summer of 1876. Refined had, of course, responded to the rise. But as the fall came on and the exporters prepared to load their cargoes, the syndicate demanded a price for refined much above that for which the market price of crude called. The embargo which followed has already been described in Chapter VII of this narrative. It was as straight a hold-up as our commercial history offers, rich as it is in that sort of operations. From October to February refined oil was held at a price purely arbitrary. It was the first fruits of the Great Scheme.

The winter's work was a great one for the Standard Combination. It not only demonstrated that Mr. Rockefeller was correct in his theory that the way to make oil dear was to refuse to sell it cheap, but not since the coup of 1872, with the South Improvement Company, had Mr. Rockefeller reaped such rewards. The profits were staggering. One of the leading gentlemen in this pretty affair told the writer once that he had sold one cargo at thirty-five cents a gallon, oil which cost him on board the ship a trifle under ten cents. To-day one-fourth of a cent profit a gallon is considered large on export oil. The Standard Oil Company of Ohio had always paid a good dividend,[7] but the year of this raid, 1877, it surpassed all bounds. On a capitalisation of $3,500,000 it paid $3,248,650.01, only a fraction less than 100 per cent. One of its stockholders, the late Samuel Andrews, when on the witness-stand in 1879, said they might have paid the dividend twice over and had money to spare.

The profits were great, but notice the forces set in motion by this coup. The exporters were angry. The buyers in Europe were angry. If the Americans are going to force up prices in this way, they said, we will not buy their refined oil. We will import their crude and refine it ourselves. We will go back to shale oil. A first result, then, of this attempt to hold prices up to a point conspicuously out of proportion to the raw product was that the exports of illuminating oil fell off—they were less by a million gallons in 1878 than in 1877. In the United States the market was threatened in the same way. There had been much trouble in the years just preceding these events with extortionate prices for gas—particularly in New York and Brooklyn. Illuminating oil was so much cheaper that it had been largely substituted, but this artificial forcing of the oil market in 1876-1877 caused a threat to return the next year to gas.

The effect on the refiners who were operating with Mr. Rockefeller in running arrangements was decidedly bad. Each refiner was under bonds to use only a certain percentage of his capacity, and to shut down entirely if Mr. Rockefeller said so. Scofield, Shurmer and Teagle, independents of Cleveland, who had yielded to the attractiveness of Mr. Rockefeller's scheme, and had gone into a running arrangement with him to limit their output, made $2.52 a barrel on their oil from July, 1876, to July, 1877! They had been satisfied with thirty-four cents profit a barrel the year before. Since making oil paid so well, why not make more? Why keep their allotment down to exactly 85,000 barrels, as they had agreed, when they were prepared to make 180,000? They did not. They put out a few extra thousand barrels each year. Others did the same. It was, of course, fatal to the "good of the oil business." Not only did these profits tempt many refiners to overrun their allotment; the few independents left profited by the prices and increased their plants; the great Empire Transportation Company combined refineries with its pipe-lines as Mr. Rockefeller was adding pipe-lines to his refineries. Thus competition was stimulated.

The effect on the men who produced oil was, of course, bad. They had found it impossible at any time, while the refined was kept so high, to force crude up to a corresponding point, though every effort was made. The producers threatened to combine and refine their own oil. When the Empire Transportation Company went into refining the producers heartily favoured the movement, and throughout the next year a severe competition kept prices down. The Empire was finally wiped out; the producers, aroused by this failure, combined against the Standard in one of the greatest associations they ever had. From 1878 to 1880 they fought continuously to restore competition. They secured the introduction into Congress of a bill to regulate interstate commerce; they fought for more drastic laws against railroad discrimination in the state of Pennsylvania; they persuaded the state to prosecute the Pennsylvania Railroad for disrimination; they indicted Mr. Rockefeller and eight of his colleagues for criminal conspiracy; and they supported by money and influence a scheme for a seaboard pipe-line connected with the independent refineries.[8]

If one will look at the chart he will see graphically the effect on Mr. Rockefeller's ambition of this fundamentally sound independent movement. The margin between crude and refined, thrust up to over twenty cents by the combination of 1878, fell rapidly under the combined efforts of the independents through 1877, 1878 and 1879. In the latter year it touched five cents for the first time in the history of the business. Competition resulting in economies, in a revolutionising transportation invention—the seaboard pipe-line

1876 TO 1880.

Fragment of chart, showing decline in margin after the coup of 1876-1877, caused by alliance of independent oil men and the success of the first seaboard pipe-line.

—in a greatly extended foreign market, brought down this margin in 1879. Nothing else.

Those who have read this history know what became of the competitive movement of these years of 1878-1879. They remember how the Producers' Union compromised its suits and abandoned its efforts for interstate commerce regulation. They remember, too, how, just before the great seaboard pipe-line project was proved to be a success, all but one of the independent refineries were, by one means or another, persuaded to sell or to combine with the Standard, leaving the Tidewater without an outlet for its oil. Before the end of 1879 the Standard claimed ninety-five per cent, of the refining business. Now examine the chart for the effect on the price of oil in 1880, of this doing away with competition—another sudden uplift of the price of refined, this time without the excuse of a rise or probable rise in crude. For three years oil had not been sold so high as it was in 1880, when the exporters began to take on their winter's supply. An interesting contemporary account of this coup of 1880, and the way in which it was managed, is found in the excellent monthly Petroleum Trade Report, published by John C. Welch. It is dated November, 1880, and headed "Very Sharp Practice":

"There is made each day in New York what is known as an official quotation for refined oil, this official quotation being made as a matter of convenience in cabling the price of refined oil throughout the world. Refined oil not being sold at an open board, it is sometimes difficult to quote it accurately, but by having an 'official quotation' this can be quoted, and the difficulty is supposed to be, in a measure at least, remedied. The 'official quotation' is made by three petroleum brokers appointed by the Produce Exchange for that purpose, who meet each day after exchange hours for the purpose of establishing it. There is one party, and one party only, that have very large lots to sell, and so important a position do they hold in the business that their prices are ordinarily the market. Of course, to make transactions, their prices and buyers' prices have to come together, and transactions establish a market much better than prices offered to buy or sell at, but without transactions. At many times, if the Standard do not sell, there are no transactions, and, consequently, the Standard's asking price is leaned upon to establish an official quotation. During September, the official quotation went up from 9⅜ cents to 11⅞ cents, with comparatively little demand, as the foreign stocks were large, and very little oil was required to supply the world's wants. The upward movement was, consequently, purely arbitrary. Arbitrary prices are, however, a part of the Standard's every-day life, and I am not taking at this time any exception to them. All through October and up to November 13, the official quotation was 12 cents, or sometimes a little over and sometimes a little under, and as this price did not meet the views of buyers to but slight extent, the Standard were supposed to be exercising a Roman virtue in not selling. Twelve cents continued as the official quotation to November 13, without any wavering, but from the I3th to the i8th, while '12 cents asked by refiners' continued in the quotation, such sentences as these were included at different dates: 'Other lots obtainable at 11 cents.' 'Sales at 10½ cents, offered at that.' 'Other lots obtainable at irregular prices, from 10 to 10½ cents.' On November 18, the quotation was '10 to 12 cents.' I give the following quotation of the New York refined market as published in my Oil City daily report of November 11: 'The New York market yesterday closed, secretly offered and unsalable at 11½ cents, and probably at 11¼ cents by resales and outside refiners, and likely by Standard, though they openly ask 12.'

"The point that seems apparent is that the official quotation of 12 cents ceased to be an honest quotation a considerable time before it was abandoned. The committee making the quotation can probably justify their position by the custom of the trade of regarding the prices the Standard openly ask as the market, nevertheless they, and the Produce Exchange whom they represent, were the bulwark from behind which the Standard were able to get off their hot shot against the consuming trade in the United States and the consuming trade in Europe, who all this time were buying Standard oil on the basis of 12 cents at New York, the supplies at the time being drawn from their stock in Europe and from their various depots in the United States."

But the performance of 1876 and 1877 was not forgotten in Europe. In 1879 the exporters and buyers from all the great foreign markets had met in Bremen in an indignation meeting over the way the Standard was handling the oil business. Remonstrances came from the consuls at Antwerp and Bremen to our State Department concerning even the quality of oil which had been sent to Europe by the Standard. John C. Welch, who was abroad in 1879, was told by a prominent Antwerp merchant: "I am of the opinion that if the petroleum business continues to be conducted as it has been in the past in Europe, it will go to smash."[9] The attempt to repeat in 1880 what had been done in 1876 failed. The exports of illuminating oil that year fell much below what they had been the year before. In 1879, 365,000,000 gallons of refined oil were exported; in 1880, only 286,000,000 gallons. Exports of crude, on the contrary, rose from about 28,000,000 gallons to nearly 37,000,000 gallons. The foreigners could export and refine their own oil cheaper than they could buy from Mr. Rockefeller. Competition was after him, too, for the Tidewater, whose refineries he had cut off, had stored their oil, built new plants, and were again ready to compete in the market.

This third corner of the oil market seems to have convinced Mr. Rockefeller and his colleagues at last that, however great the fun and profits of making oil very dear, in the long run it does not pay; that it weakens markets and stimulates competition. They learned a lesson in these years they have never forgotten—that when you make a scoop it must not be so big that you will never have a chance to make another one; that if you want to keep your power to manipulate the market you must use that power so modestly that the public in general will not realise you have it. Again and again the effect of the experiences of 1872, 1876 and 1880 crops out in the testimony of Standard officials. Benjamin Brewster once said to a Federal Investigating Committee, which had asked if the Standard could not fix the price of oil as it wished: "At the moment many things may be done, but the reaction is like a relapse of typhoid fever. The Standard Oil Company can never afford to sell goods dear. The people would go to dipping tallow candles in the old-fashioned way if we got the price too high." The after-effects of the first great raids, then, were salutary. The Standard learned the limitations set on monopolies by certain great economic laws.

But if the Standard Oil Company learned in its first attempts to raise the price of oil that they could not in the long run afford to make from 100 to 350 per cent., they by no means gave up their attempt to keep their control, and to hold up profits as high as they could without injuring the market or inviting too strong competition. If one will look at the chart showing the fluctuations from 1879, when control was achieved, to the beginning of 1889, one will find that for ten years the margin between refined oil and crude never fell below the point reached by competitive influences in the former year, though frequently it rose considerably above. Yet it is in this period that the Standard did all its great work in extending markets, in developing by-products, and in introducing the small and varied economies on which it rests its claim to be a great

1879 TO 1889.

Fragment of chart, showing how margin reached in 1879 by competition was raised and sustained for ten years under the monopoly achieved by the Standard Oil Company in 1880. The sudden rise in refined in the fall of 1880 was a purely arbitrary price. Notice that crude was stationary at the time.

public benefactor. The first eight years of its existence had been spent in bold and relentless warfare on its competitors. Competition practically out of the way, it set all its great energies to developing what it had secured. In this period it brought into line the foreign markets and aided in increasing the exports of illuminating oil from 365,000,000 gallons in 1879 to 455,000,000 in 1888; of lubricating, from 3,000,000 to 24,000,000, and yet this great extension of the volume of business profited the consumer nothing. In this period it laid hands on the idea of the Tidewater, the long-distance pipe-lines for transporting crude oil, and so rid itself practically of the railroads, and yet this immense economy profited the public nothing. In spite of the immense development of this system and the enormous economies it brought about a system so important that Mr. Rockefeller himself has said: "The entire oil business is dependent upon this pipe-line system. Without it every well would shut down, and every foreign market would be closed to us"—the margins never fell the fraction of a cent from 1879 to 1889, though it frequently rose. In this period, too, the by-products of oil were enormously increased. The waste, formerly as much as ten per cent, of the crude product, was reduced until practically all of the oil is worked up by the Standard people, and yet, in spite of the extension of by-products between 1879 and 1889, the margin never went below the point competition had forced it to in 1879.

The enormous profits which came to the Standard in these ten years by keeping out competition are evident if we consider for a moment the amount of business done. The exports of illuminating oil in this period were nearly 5,000,000,000 gallons; of this the Standard handled well toward ninety per cent. Consider what sums lay in the ability to hold up the price on such an amount even an eighth of a cent a gallon. Combine this control of the price of refined oil with the control over the crude product, the ability to depress the market for purchasing, an ability used most carefully, but most constantly; add to this the economies and development Mr. Rockefeller's able and energetic machine was making, and the great profits of the Standard Oil Trust between 1879 and 1889 are easily explained. In 1879, on a capital of $3,500,000, the Standard Oil Company paid $3,150,000 dividends; in 1880 it paid $1,050,000. In 1882 it capitalised itself at $70,000,000. In 1885, three years later, its net earnings were over $8,000,000; in 1886, over $15,000,000; in 1888, over $16,000,000; in 1889, nearly $15,000,000. In the meantime the net value of its holdings had increased from $72,000,000; in 1883, to over $101,000,000. While the Standard was making these great sums, the men who produced the oil saw their property depreciating, and the value of their oil actually eaten up every two years by the prices the Standard charged for gathering and storing it.

But to return to the chart. With the beginning of 1889 the margin begins to fall. This is so in spite of a rising crude line. It would look as if the Standard Oil Company had suddenly had a change of heart. In the report of that year's business made to the trustees of the Standard Oil Trust, the following elaborate and interesting calculation was presented:

"The quantity of crude oil consumed by the Standard manufacturing interests in 1889 was 896,250,325 gallons, or 20,339,293 barrels, an increase over the previous year of 119,073,589 gallons, or 2,835,085 barrels, an increase of 15.3 per cent.

"The sales of crude oil by our interests for purposes other than their own manufacture were 135,788,959 gallons, or 3,232,832 barrels, an increase of 43¼ per cent. over the previous year, making the total consumption of crude oil through our interests 1,032,029,284 gallons, or 24,572,126 barrels, an increase over 1888 of 3,809,917 barrels, or 18.35 percent., and exceeding the consumption of 1887, which was the largest of any previous year, by 12.7 per cent.

"The quantity of refined oil produced was 666,742,547 gallons, or 13,334,851 barrels of 50 gallons each; of lubricating paraffine and compounded oils 43,862,795 gallons, or 877,256 barrels, and of other products 160,712,183 gallons, or 3,214,243 barrels, making a total of all products of 871,371,525 gallons, or 17,426,350 barrels, valued at over $46,000,000.

"The average cost of the crude consumed in refining was .211 of a cent more than in 1888, while the average price realised per gallon of crude was .090 of a cent less, showing a decrease in the margin between the crude and finished product of .301 of a cent. This represents a saving to the consumer over what the finished products would have cost him if the same margin had been maintained on the increased price of crude of $2,697,000. This has been done without a corresponding loss to our interests by a decrease in cost of manufacturing and marketing, and by the increased quantity handled .204 of a cent, effecting a saving of $1,860,000, and the difference has been more than made up by further reductions of cost of marketing by our distributing interests, as well as in the increased quantity handled. Although the average price of crude has been the highest this year of any of the last five years, the increase over the price of 1887 (when the price on both crude and refined was the lowest for that period) being about 22¼ per cent., the average price of products has increased but 12¼ per cent., showing a saving to the consumer of 10 per cent. We have therefore continued to make good the claim that the Standard has heretofore maintained of cheapening the cost of the products to the consumers by giving them the benefits of the saving in costs effected by consolidation of interests."[10]

This certainly sounds just—even philanthropic. It is exactly what the consumer claims is his due—to have a share of the economies which undoubtedly may be effected by such complete and intelligent consolidation as Mr. Rockefeller has effected. But was it combination that caused this falling of the margin? As a matter of fact this lowering of the margin was the direct result of competition. In 1888 a German firm, located in New York City, erected large oil plants in Rotterdam and Bremerhaven. They put up storage tanks at each place of 90,000 barrels' capacity. They also established a storage depot of 30,000 barrels at Mannheim, and took steps to extend their supply stations in Germany and Switzerland. They built tank steamers in order to ship their oil in bulk. These oil importers allied themselves with certain independent refiners, and interested themselves also in the co-operative movement which the producers of Pennsylvania were striving to get into operation at this time. The extent of the undertaking threatened serious competition. In the same year imports of Russian oil into the markets of Western Europe began for the first time to assume serious proportions. Russian oil had, from the beginning, been a possible menace to American petroleum, for the wonderful fields on the Caspian were known long before oil was "struck" in Pennsylvania. They did not begin to be exploited in a way to threaten competition until late in the eighties. In 1885 consuls at European ports began to report its appearance—fifty barrels were landed at Bremen that year as against 180,855 of American oil. In this year, too, the first Russian oil went to Asia Minor, where "Pratt" oil had long held sway. The first cargo reported at Antwerp was in March, 1886. In April, 1890, the consul at Rotterdam, in calling attention to the independent American competition, said of Russian oil: "It is no longer a serious competitor for the petroleum trade of Western Continental Europe." The consul said that while the American oil shipments to the five principal continental ports were fully 4,000,000 barrels per year, those of Russian were less than a tenth of that number. However, a growth of 400,000 barrels in five years was something, and the Standard Oil Trust was the last to underestimate such a growth. Prices of export oil immediately fell. There was nothing in the world that gave oil consumers the benefit of the Standard's savings by economies in 1889 but the competition threatened by Russia and the American and German independent alliance. The Standard, to offset it, not only lowered its price, but it followed the German company to Rotterdam in order to put up an oil plant similar to the one which had been erected by those independents. They also purchased at this time the great oil establishments at Bremen and Hamburg which had hitherto been owned and operated by Germans. A full account of this new development in the oil trade was reported by the American consul at Rotterdam in April of 1890, and is to be found in the consular reports of that year.

Follow the lines a little farther. Notice how, in 1892, the price of refined oil begins to fall, although crude is stationary. Notice how the refined line remains steady throughout 1893 and 1894, although the crude line steadily rises. This went on for nearly three years, until there was a margin of only three cents between crude and refined oil. The barrel, which is always reckoned in the official quotations of export refined oil, costs two and a half cents per gallon, and the price of manufacturing is usually put at one-half a cent. The cost of transporting the oil was not covered by the margin the

1890 TO 1904.

Fragment of chart, showing relation between crude and refined oil in the last fourteen years. Notice effect on margin from 1890 to 1894 of rise of strong competitive forces. Notice also how margin between price of crude and of domestic oil increased in the winter of 1903-1904, during the coal famine.

greater part of the year 1894. Now, the Standard Oil Company were not selling oil at a loss at this time out of love for the consumers, although they made enough money in 1894 on by-products and domestic oil to have done so—their net earnings were over $15,000,000 in 1894, and they reckoned an increase in net value of property of over $4,000,000—they were fighting Russian oil and the independent combination started in 1889. By 1892 this combination was in active operation. The extent of this movement was described in the last chapter of this narrative. At the same time certain large producers in the McDonald oil field built a pipe-line from Pittsburg to Baltimore, the Crescent Line, and began to ship crude oil to France in great quantities. It looked as if both combinations meant to do business, and the Standard set out to get them out of the way. One method they took was to prevent the refiners in the combination making any money on export oil.

The extent to which cutting was carried on for two years, beginning with the fall of 1892, has been referred to in the last chapter, but is perhaps worth repeating in this connection. In January of 1892 crude oil was selling at 53½ cents a barrel at the wells, and refined oil for export at 5.33 cents a gallon in barrels. Throughout the year the price of crude advanced, until in December it was 78⅜ cents. Refined, on the contrary, fell, and it was actually 18 points lower in December than it had been twelve months before. Throughout 1894 the Standard kept refined oil down; the average price of the year was 5.19 cents a gallon, in face of an average crude market of 83¾ cents, lower than in January, 1893, with crude at 53½ cents a barrel.

After two years they gave it up. It was too expensive. The Crescent Line sold to them, but the other independents were too plucky. They had lost money for two years, but they were still hanging on like grim death, and the Standard concluded to concentrate their attacks on other points of the combination rather than on this export market where it was costing them so much.

About the end of 1894 the depression of export oil was abandoned, as the chart shows. Notice that from 1895 to 1898 the margin remained at about four cents, that in 1900 it rose to six cents, and from that time until June, 1904, it swung between four and a half and five. The increasing competition in Western Europe of independent American oils, and the rapid rise since 1895, particularly of Russian oil, are what has kept this margin down. It is doubtful, such is the growing strength of these various competitive forces, if the Standard Oil Trust will ever be able to put up the margin on export oils. If there were only the American independents to reckon with, a compromise might be possible, but Russia, Burmah and Sumatra are all in the game. By 1896 Russia was exporting 210,000,000 gallons of petroleum products (America in that year exported over 931,000,000 gallons), and these products were going to nearly every part of Europe and Asia. They began to cut heavily into the trade of the Standard in China, India, Great Britain and France. By 1899 the exports of Russian oil were over 347,000,000 gallons; in 1901, over 428,000,000 gallons. In China, India, and Great Britain particularly, has the Russian competition increased. While at one time the Standard Oil Company had almost the entire oil trade at the port of Calcutta, last year, 1903, out of 91,500,000 gallons imported, only about 6,500,000 gallons were of American oil. In China, Sumatra oil is now ahead of American, the report for 1903 being: American, 31,060,527 gallons; Sumatra, 39,859,508.

For the Standard there is good profit in this margin of four and a half cents for export oil. The expenses the margin must cover are the transportation of the crude from the wells to New York, the cost of manufacture, the barrel and the loading. For twenty-five years the published charge of the Standard Oil Company for gathering oil from the wells has been twenty cents a barrel. The charge for bringing it to New York has been forty cents, a little less than one and a half cents a gallon. It costs, by rough calculation, one-half a cent to make the oil and load it. The barrel is usually reckoned at two and a half cents. Here are four and a half cents for expenses—the entire margin. Where the Standard has the advantage is in its ownership of oil transportation. A common carrier gathering and transporting in 1902 all but perhaps 10,000 barrels of the 150,000 barrels' daily production of Eastern oil, the service for which the outsider pays sixty cents, costs it from ten to twelve cents at the most liberal estimate. Here is over a cent saved on a gallon, and a cent saved, where millions of gallons are in question, makes not only great profits, but keeps down competition. The refiner who to-day must pay the Standard rates for transportation cannot compete in export oil with them. In January of 1904, when the chart shows the margin to have been about four and three-quarter cents, an independent refiner in the state of Ohio, dependent on the Standard for oil, gave the writer a detailed statement of costs and selling prices of products in his refinery. According to his statement he lost one and three-fifth cents on his export oil. He was forced, of course, to pay Standard transportation prices for crude and railroad charges for refined from Ohio to New York harbour.[11]

That there would have been such a transportation situation to-day had it not been for the discrimination by the railways, which threw the pipes into the Standard's hands in the first place, and the long story of aggression by which the Standard has kept out rival pipes, and so been able for twenty-five years to sustain the price for transportation, is of course evident. To-day, as thirty years ago, it is transportation advantages, unfairly won, which give the Standard Oil Company its hold. It is not only on transportation that the Standard to-day has great advantages over the independent refiner in the export market. As said at the beginning of this chapter, the Standard Oil Company "makes the price of refined oil"—within strict limits. Of course, making the market, it has all the advantages of the "inside track." Its transactions can be carried on in anticipation of the rise or fall. For instance, in January of 1904, when there were strong fluctuations in the water-white (150 degrees test) prices, the agent of an independent refiner, who was in Wall Street trying to keep track of markets for out-of-town competitors, reported the price as 9.20 cents a gallon. The refiners' goods were refused on the ground that this was above the market. The Standard Oil export man and a broker who worked with the company were consulted. The market was 9.20. Further investigation, however, showed that at headquarters the figure given out privately was 8.70 cents. The disadvantage of the outsider in disposing of his goods is obvious. The Standard makes the official market, and undersells it. The situation seems to be the same in practice as that described by Mr. Welch, in 1880, though now the fiction of a committee of brokers has been done away with. Of course there is nothing else to be expected when one body of men control a market.

Thus far the illustrations of Mr. Rockefeller's use of his power over the oil market have been drawn from export oil. It is the only market for which "official" figures can be obtained for the entire period, and it is the market usually quoted in studying the movement of prices. It is of this grade of oil that the largest percentage of product is obtained in distilling petroleum. For instance, in distilling Pennsylvania crude, fifty-two per cent. is standard-white or export oil, twenty-two per cent. water-white—the higher grade commonly used in this country—thirteen per cent. naphtha, ten per cent. tar, three per cent. loss. The runs vary with different oils, and different refiners turn out different products. The water-white oils, while they cost the same to produce, sell from two to three cents higher. The naphtha costs the same to make as export oil, but sells at a higher price, and many refiners have pet brands, for which, through some

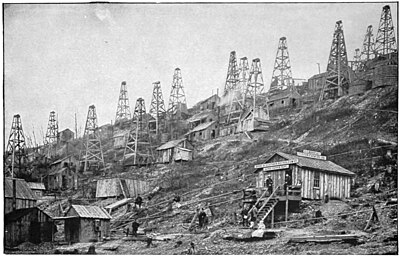

A typical oil farm of the early days

Turn now to the price of domestic oil, and examine the chart to see if we have fared as well as the exporters. The line C on the chart represents the price per gallon in New York City of 150° water-white oil in barrels from the beginning of 1881 to June, 1904.[12] The figures used are those of the Oil, Paint and Drug Reporter. A glance at the chart is enough to show that the home market has suffered more violent, if less frequent, fluctuations than the export market. A suggestive observation for the consumer is the effect of a rise in crude on the price of domestic oil. The refined line usually rises two or three points to every one of the crude line. It is interesting to note, too, how frequently high domestic prices are made to offset low export prices; thus, in 1889, when the Standard was holding export oil low to fight competition in Europe, it kept up domestic oil. The same thing is happening to-day. We are helping pay for the Standard's fight with Russian, Roumanian and Asiatic oils. But this line, while it shows what the New York trade has paid, is a poor guide for the country as a whole. Domestic oil, indeed, has no regular price. Go back as far as anything like trustworthy documents exist, and we find the most astonishing vagaries, even in the same state. For instance, in a table presented to a Congressional Committee in 1888, and compiled from answers to letters sent out by George Rice, the price of 110° oil in barrels in Texas ranged from 10 to 20 cents; in Arkansas, of 150° oil in barrels, from 8 to 18; in Tennessee, the same oil, from 8 to 16; in Mississippi, the same, from 11 to 17. In the eighties, prime white oil sold in barrels, wholesale, in Arkansas, all the way from 8 to 14 cents; in Illinois, from 7½ to 10; in Mississippi, from 7¼ to 13½; in Nebraska, 7½ to 18; in South Carolina, 8 to 12½; and in Utah, 13 to 23. Freight and handling might, of course, account for one to two cents of the difference, but not more.

A table of the wide variation in the price of oil, compiled in 1892, showed the range of price of prime white oil in the United States to be as follows:

In barrels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

6 to 25 cents | |

In cases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

14 to 3412 cents | |

In bulk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

312 to 25 cents | |

The same wide range was found in water-white oil:

In barrels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

612 to 30 cents per gallon | |

In cases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

16 to 35 cents per gallon | |

In bulk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

312 to 29 cents per gallon | |

In 1896 an investigation of prices of oil sold from tank-wagons in the different towns of Ohio, in the same week, was made, and was afterward offered as sworn testimony in a trust investigation in that state. The price per gallon ranged from 4¾ cents to 8¾ cents.

The most elaborate investigation of oil prices ever made was that instigated by the recent Industrial Commission. In February, 1901, the commission sent out inquiries to 5,000 retail dealers, scattered from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from the Lakes to the Gulf, asking the prices of certain commodities, among them illuminating oils; 1,578 replies were received. The tables prepared offered striking examples of the variability of prices—thus:

In Colorado the wholesale price of illuminating oil (150° test) varied from 13 to 20 cents; in Delaware, 8 to 10; in Illinois, 6 to 10; in Alabama, 10.50 to 16; in Michigan, 5.50 to 12.25; in Missouri, 7.50 to 12.50; in Kentucky, 7 to 11.50; in Ohio, 5.50 to 9.75; in California, 12.50 to 20; in Utah, 20 to 22; in Maine, 8.25 to 12.75 (freight included in all these prices).

The difference between the highest and the lowest wholesale prices in the same states varies from 8 cents in Oregon (12.50 to 20.50) to 1.50 in Rhode Island (8.50 to 10). Of course, in the former case, two or even three cents of the difference may be due to freight, but hardly more. Take adjoining states, for instance. In Vermont there is a difference of 4.50 cents between the highest and lowest price of oil; in New Hampshire, only 1.75. In Delaware there is a difference of 2 cents; in Virginia, of 6.

Compare, now, the lowest price in different states. In Ohio and Pennsylvania oil was sold as low as 5.50; 6.50 is the lowest in New York State, 8.50 the lowest in Rhode Island, and 7 the lowest in New Jersey. In Indiana oil sells as low as 5.50, but in Kansas nothing below 8.50 is reported (the freight rate to Atchison, Kansas, from Whiting, Indiana, which supplies both of these states, is 1.7 per gallon. The freight rate from Whiting to Indianapolis is .5 per gallon).

Not long ago there fell into the writer's hands a sheet from one of the ledgers forming a part of the Standard Oil Company's remarkable system of bookkeeping. This sheet gave the cost and selling price per gallon of different grades of refined oil at over a dozen stations in the same state in October, 1901. In the account of cost of oil were included net cost, freight, inspection, cost of barrels and cost of marketing. The selling price was given and the margin of profit computed. The selling price of water-white from tank-wagons (it is customary for Standard tank-wagons to deliver oil from their stations to local dealers) ranged from 8½ to 11½ cents, and the profit on the oil sold from the wagons varied from about one-half cent to over three cents.

Now, in considering these differences, liberal allowance for freight rates must be made. Something of what these allowances should be can be judged from the table of oil freights which the Industrial Commission published with its schedule of prices. From this table many interesting comparisons can be made. For instance, it cost the Standard Oil Company (if they paid the open rate their rivals did) 1.5 cents to send a gallon of oil from Whiting, Indiana, their supply station, to Mobile, Alabama. They sold their oil in Alabama at wholesale from 11½ to 16 cents. The net cost of this oil was under five cents in February, 1901. It cost them the same 1.5 cents to send a gallon of oil to Des Moines, Iowa (if they paid the open rate), but in Iowa they sold it from 7 to 11. The freight from Whiting to New Orleans was the same 1.5 cents, but prices in Louisiana ranged from 9 to 14 cents. According to the investigation the average wholesale price of oil, including freight, ranged from 8.27 in Pennsylvania to 25.78 in Nevada.

Freights and handling considered, there is, it is evident, nothing like a settled price or profit for illuminating oil in the United States. Now, there is no one who will not admit that it is for the good of the consumer that the normal market price of any commodity should be such as will give a fair and even profit all over the country. That is, that freights and expense of handling being considered, oil should sell at the same profit in Texas as in Ohio. That such must be the case where there is free and general competition is evident. But from the beginning of its power over the market the Standard Oil Company has sold domestic oil at prices varying from less than the cost of the crude oil it took to make it up to a profit of 100 per cent, or more. Wherever there has been a loss, or merely what is called a reasonable profit of, say, ten per cent., an examination of the tables quoted above shows conclusively it has been due to competition. The competition is not, and has not been since 1879, very great. In that year the Standard Oil Company claimed ninety-five per cent. of the refining interests of the country. In 1888 they claimed about eighty per cent.; in 1898, eighty-three per cent. This five to seventeen per cent. of independent interest is too small to come into active competition, of course, at all points. So long as one interest handles eighty-three per cent. of a product it is clear that it has the trade as a whole in its hands. The competition it encounters will be local only. But it is this local competition, unquestionably, that has brought down the price of oil at various points and caused the striking variation in prices recorded in the charts of the Industrial Commission and other investigations. The writer has before her a pile of a hundred or more letters written in the eighties by dealers in twelve different states. These letters tell the effect on the prices of the introduction of an independent oil into a territory formerly occupied exclusively by the Standard:

Calvert, Tenn.—The Waters-Pierce Oil Company (Standard) so reduced the price of their oil here when mine arrived that I will have some trouble to dispose of mine.

Chattanooga, Tenn.—… Cut the price of oil that had been selling at 21 cents to 17 cents.

Pine Bluff, Ark.—While the merchants here would like to buy from some other than the Standard they cannot afford to take the risks of loss. We have just had an example of one hundred barrels opposition oil which was brought here, which had the effect of bringing Waters-Pierce Oil Company's oil down from 18 to 13 cents—one cent less than cost of opposition, with refusal on their part to sell to anyone that bought from other than their company.

Vicksburg, Miss.—The Chess Carley Company (Standard) is now offering 110° oil at nine cents to any and every one. Shall we meet their prices? All they want is to get us out of the market, then they would at once advance price of oil.

These are but illustrations of the entire set of letters; prices dropped at once by Standard agents on the introduction of an independent oil. A table offered to Congress in 1888, giving the extent of their cutting in the Southwest, shows that it ranged from 14 to 220 per cent.

Every investigation made since shows that it is the touch of the competitor which brings down the price. For instance, in the cost and profit sheet from a Standard ledger referred to above, there was one station on the list at which oil was selling at a loss. On investigation the writer found it to be a point at which an independent jobber had been trying to get a market. If one examines the tables of prices in the recent report of the Industrial Commission, he finds that wherever there is a low price there is competition. Thus, at Indianapolis, the only town in the state of Indiana reporting competition, the wholesale price of oil was 5½ cents, although forty out of the fifty-three Indiana towns reporting gave from 8 cents to 10½ cents as the wholesale price per gallon. (These prices included freight. Taking Indianapolis as a centre, the local freight on oil to any point in Indiana is in no case over a cent.) In April, 1904, inquiry showed the same striking difference between prices in Indianapolis, where six independent companies are now established, and neighbouring towns to which competition has not as yet reached.

The advent of an independent concern in Morristown, New Jersey, brought down the price to grocers to 7½ cents and to housewives to 10, but in the neighbouring towns of Elizabeth and Plainfield, where only the Standard is reported, the grocers pay 9 cents and the housewives 12 and 11, respectively. In Akron, Ohio, where an independent company was operating at the time the investigation was made, oil was sold at wholesale at 5¾ cents; at Painesville, nearer Cleveland, the shipping point, at 9¼ cents. In Richmond, Virginia, one dealer reported to the commission a wholesale price of 5 cents, and added: "A cut rate between oil companies; has been selling at 9 and 10 cents."

In the month of April of 1904 150° oil was selling from tank-wagons in Baltimore, where there is competition, at 9 cents. In Washington, where there is no competition, it sold at 10½ cents, and in Annapolis (no competition) at 11 cents. In Seaford, Delaware, the same oil sold at 8 cents under competition. The freight rates are practically the same to all these points. And so one might go on indefinitely, showing how the introduction of an independent oil has always reduced the price. As a rule, the appearance of the oil has led to a sharp contest or "Oil War," at which, not infrequently, both sides have sold at a loss. The Standard, being able to stand a loss indefinitely, usually won out.

An interesting local "Oil War," which occurred in 1896 and 1897 m New York and Philadelphia, figured in the reports of the Industrial Commission, and illustrates very well the usual influence on Standard prices of the incoming of competition. On March 20, 1896, the Pure Oil Company put three tank-wagons into New York City. The Standard's price of water-white oil from tank-wagons that day was 9½ cents, and the Pure Oil Company followed it. In less than a week the Standard had cut to 8 cents[13] along the route of the Pure Oil Company wagons. In April the price was cut to 7 cents. By December, 1896, it had fallen to 6 cents; by December, 1897, to 5.4. It is true that crude oil was falling at this time, but the fall in water-white was out of all proportion. For, while between the price of refined on March 20 and the average price of refined in April along the Pure Oil Company route, there was a fall of 2½ cents, in crude there was a fall of but four-tenths of a cent. Refined fell from 7 cents in April to 6 cents in May, and crude fell one-tenth of a cent. John D. Archbold, in answering the figures given by the Pure Oil Company to the Industrial Commission, accused them of "carelessness," and gave the average monthly price of crude and refined to show that no such glaring discrepancy had taken place. Mr. Archbold gives the average price in March, for instance, as 7.98 and in April as 7.31 cents. However, his price is the average to "all the trade of Greater New York and its vicinity," whereas the prices of the Pure Oil Company are those they met in their limited competition. As Professor Jenks remarked at the examination: "It might easily be, therefore, that your" (Standard) "average price would be what you had given, and that to a good many special customers with whom the Pure Oil Company was trying to deal it could be five and a half cents." That this was the fact seems to be proved by the quotations for water-white oil from tank-wagons, which were published from week to week in trade journals like the Oil, Paint and Drug Reporter. These prices show 9⅞ cents for water-white on March 21, and an average of 9.4 cents in April. Evidently only a part of the trade of "all Greater New York and vicinity" got the benefit of averages quoted to the Industrial Commission by Mr. Archbold.

If competition persists the result usually has been permanently lower prices than in territory where competition has been run out or has never entered. For instance, why should oil be sold to a dealer at nearly four cents more on an average in Kansas than in Kentucky, when the freight from Whiting to Kansas is only a cent more? For no reason except that in Kentucky there has been persistent competition for twenty-five years, and in Kansas none has ever secured a solid foothold. Why should Colorado pay an average of 16.90 cents for oil per gallon and California 14.60 cents, when the freight from Whiting differs but one-tenth of one cent? For no reason except that a few years ago competition was driven from Colorado, and in California it still exists.

Indeed, any consecutive study of the Standard Oil Company's use of its power over the price of either export or domestic oil must lead to the conclusion that it has always been used to the fullest extent possible without jeopardising it; that we have always paid more for our refined oil than we would have done if there had been free competition. But why should we expect anything else? This is the chief object of combinations. Certainly the candid members of the Standard Oil Company would be the last men to argue that they give the public any more of the profits they may get by combination than they can help. One of the ablest and frankest of them, H. H. Rogers, when before the Industrial Commission in 1899, was asked how it happened that in twenty years the Standard Oil Company had never cheapened the cost of gathering and transporting oil in pipe-lines by the least fraction of a cent; that it cost the oil producer just as much now as it did twenty years ago to get his oil taken away from the wells and to transport it to New York. And Mr. Rogers answered, with delightful candour: "We are not in business for our health, but are out for the dollars."

John D. Archbold was asked at the same time if it were not true that, by virtue of its great power, the Standard Oil Company was enabled to secure prices that, on the whole, were above those under competition, and Mr. Archbold said: "Well, I hope so."[14]

But these are frank answers, perhaps surprised out of the gentlemen. The able and wary president of the great concern, John D. Rockefeller, is more cautious in his admissions. On the witness-stand in 1888 he was forced to admit, after some skilful evasion, that the control the Standard Oil Company had of prices was such that they could raise or lower them at will. "But," added Mr. Rockefeller, "we would not do it." The whole colloquy between the examiner and Mr. Rockefeller is interesting:

Q. Isn't it a fact that the nine trustees controlling the large amount of capital which the Standard Oil Trust does could very easily advance or depress the market price of oil if they saw fit?…

A. I don't think they would.

Q. I don't ask whether they would; could they do it?

A. I suppose it would be possible for these gentlemen; if they should buy enough oil, it would make the price go up.

There was considerable sparring, Mr. Rockefeller trying to explain away his answer.

Q. I can't get you down to my question… that is a very great power to wield.

A. Certainly; an individual or a combination of men can advance the price or more or less depress the price of any commodity.

Q. But if you desire to increase—to put up the price of the refined oil, or to put down the price of the crude oil, is it within your power to do it, in the way I have indicated, by staying out of the market or going into the market to purchase, controlling 75 per cent, of the demand for the crude oil?

A. It would be a temporary effect, but that is all…

Q. By stopping the manufacture of refined oil your refineries representing so large a proportion would tend to raise the price?

A. That is something we never do; our business is to increase all the time, not to decrease.

...........

Q. Really your notion is that the Standard Oil Trust is a beneficial organisation to the public?

A. I beg with all respect to present the record which shows that it is.[15]

For many of the world it is a matter of little moment, no doubt, whether oil sells for eight or twelve cents a gallon. It becomes a tragic matter sometimes, however, as in 1902-1903 when, in the coal famine, the poor, deprived of coal, depended on oil for heat. In January, 1903, oil was sold to dealers from tank-wagons in New York City at eleven cents a gallon. That oil cost the independent refiner, who paid full transportation charges and marketed at the cost of a cent a gallon, not over 6.4 cents. It cost the Standard Oil Company probably a cent less. That such a price could prevail under free competition is, of course, impossible. Throughout the hard winter of 1902-1903 the price of refined oil advanced. It was claimed that this was due to the advance in crude, but in every case it was considerably more than that of crude. Indeed, a careful comparative study of oil prices shows that the Standard almost always advances the refined market a good many more points than it does the crude market. The chart shows this. While this has been the rule, there are exceptions, of course, as when a rate war is on. Thus, in the spring of 1904, the severe competition in England of the Shell Transportation Company and of Russian oil caused the Standard to drop export refined considerably more than crude. But, as the chart shows, domestic oil has been kept up.

As a result of the Standard's power over prices, not only does the consumer pay more for oil where competition has not reached or has been killed, but this power is used steadily and with consummate skill to make it hard for men to compete in any branch of the oil business. This history has been but a rehearsal of the operations practised by the Standard Oil Company to get rid of competition. It was to get rid of competition that the South Improvement Company was formed. It was to get rid of competition that the oil-carrying railroads were bullied or persuaded or bribed into unjust discriminations. It was to get rid of competition that the Empire Transportation Company, one of the finest transportation companies ever built up in this country, was wrested from the hands of the men who had developed it. It was to get rid of competition that war was made on the Tidewater Pipe Line, the Crescent Pipe Line, the United States Pipe Line, not to mention a number of similar smaller enterprises. It was to get rid of competition that the Standard's spy system was built up, its oil wars instituted, all its perfect methods for making it hard for rivals to do business developed.

The most curious feature perhaps of this question of the Standard Oil Company and the price of oil is that there are still people who believe that the Standard has made oil cheap! Men look at this chart and recall that back in the late sixties and seventies they paid fifty and sixty cents a gallon for oil, which now they pay twelve and fifteen cents for. This, then, they say, is the result of the combination. Mr. Rockefeller himself pointed out this great difference in prices. "In 1861," he told the New York Senate Committee, "oil sold for sixty-four cents a gallon, and now it is six and a quarter cents." The comparison is as misleading as it was meant to be. In 1861 there was not a railway into the Oil Regions. It cost from three to ten dollars to get a barrel of oil to a shipping point. None of the appliances of transportation or storage had been devised. The process of refining was still crude, and there was great waste in the oil. Besides, the markets were undeveloped. Mr. Rockefeller should have noted that oil fell from 61½ in 1861 to 25⅝ in the year he first took hold of it, and that by his first successful manipulation it went up to 30! He should point out what the successive declines in prices since that day are due to—to the seaboard pipe-lines, to the development of by-products, to bulk instead of barrel transportation, to innumerable small economies. People who point to the differences in price, and call it combination, have never studied the price-line history in hand. They do not know the meaning of the variation of the line; that it was forced down from 1866 to 1876, when Mr. Rockefeller's first effective combination was secured by competition, and driven up in 1876 and 1877 by the stopping of competition; that it was driven down from 1877 to 1879 by the union of all sorts of competitive forces—producers, independent refiners, the developing of an independent seaboard pipe-line—to a point lower than it had ever been before. They forget that when these opposing forces were overcome, and the Standard Oil Company was at last supreme, for ten years oil never fell a point below the margin reached by competition in 1879, though frequently it rose above that margin. They forget that in 1889, when for the first time in ten years the margin between crude and refined oil began to fall, it was the competition coming from the rise of American independent interests and the development of foreign oil fields that did it.

To believe that the Standard Oil Combination, or any other similar aggregation, would lower prices except under the pressure of the competition they were trying to kill, argues an amazing gullibility. Human experience long ago taught us that if we allowed a man or a group of men autocratic powers in government or church, they used that power to oppress and defraud the public. For centuries the struggle of the nations has been to obtain stable government, with fair play to the masses. To obtain this we have hedged our kings and emperors and presidents about with a thousand constitutional restrictions. It has not been possible for us to allow even the church, inspired by religious ideals, to have the full power it has demanded in society. And yet we have here in the United States allowed men practically autocratic powers in commerce. We have allowed them special privileges in transportation, bound in no great length of time to kill their competitors, though the spirit of our laws and of the charters of the transportation lines forbade these privileges. We have allowed them to combine in great interstate aggregations, for which we have provided no form of charter or of publicity, although human experience long ago decided that men united in partnerships, companies, or corporations for business purposes must have their powers defined and be subject to a reasonable inspection and publicity. As a natural result of these extraordinary powers, we see, as in the case of the Standard Oil Company, the price of a necessity of life within the control of a group of nine men, as able, as energetic, and as ruthless in business operations as any nine men the world has ever seen combined. They have exercised their power over prices with almost preternatural skill. It has been their most cruel weapon in stifling competition, a sure means of reaping usurious dividends, and, at the same time, a most persuasive argument in hoodwinking the public.

- ↑ Adapted from chart printed in Volume I of Report of Industrial Commission and brought up to date.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 57. Tables of yearly average prices of crude and refined.

- ↑ Figures used in computing this profit are from the Oil City Derrick of the period, and from practical oil refiners of that day.

- ↑ See Chapter IV

- ↑ See Chapter V

- ↑ In 1871 there was something over 132,000,000 gallons of illuminating oil exported. In 1872 it fell to about 118,000,000 gallons.

- ↑ According to the statement of the Standard Oil Company, made in a suit for taxes brought by the state of Pennsylvania in 1881, it declared dividends as follows: In 1873, year ending the first Monday in November, $347,610; in 1874, $358,605; in 1875 (the capital stock was raised from $2,500,000 to $3,500,000 in 1875), $514,230; in 1876, $501,285; in 1877, $3,248,650.01; in 1878, $875,000; in 1879, $3,150,000; in 1880, $1,050,000.

- ↑ See Chapter VII.

- ↑ Report of the Special Committee on Railroads, New York Assembly, 1879. Volume IV, page 3680

- ↑ Plaintiff's Exhibit, Number 51, in the case of James Corrigan vs. John D. Rockefeller in the Court of Common Pleas, Cuyahoga County, Ohio, 1897.

- ↑ It costs the Cleveland refiner .64 of a cent a gallon to bring oil in bulk from the Oil Regions to his refinery, and 1.44 cents per gallon to send it refined in bulk to New York.

- ↑ Trustworthy and regular quotations are not to be obtained earlier than 1881.

- ↑ Report of the Industrial Commission, 1900. Volume I, page 365.

- ↑ See Appendix, Number 58. John D. Archbold's statement on the prices the Standard receives for refined oil.

- ↑ Report on Investigation Relative to Trusts, New York Senate, 1888, pages 434-435 and 396-398.