The Meat Fetish

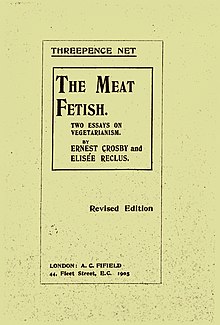

THE MEAT FETISH

THE MEAT FETISH

Two Essays on Vegetarianism

By

ERNEST CROSBY and

ELISEE RECLUS

NEW EDITION

LONDON: A. C. FIFIELD

44, FLEET STREET, E.C. 1905

Published by A. C. Fifield,

for the Humanitarian League,

53, Chancery Lane, London

PRINTED BY A BONNER, 1 & 2 TOOK'S COURT, LONDON

THE MEAT FETISH.

By Ernest Crosby.

From the æsthetic point of view slaughter-houses are upon the face of the earth, and in half-unconscious recognition of this fact we usually hide them away out of sight. It is quite possible, indeed, to go through life without ever seeing one. At the present moment I can only recall three which have ever come into my field of vision. One was out in the country, in the midst of the beautiful intervale of New Hampshire. An ugly board shanty in the fields, with a pile of hideous offal at one side and a sickening stench to leeward, to us children it was like an outpost of hell in the midst of heaven, and we shunned it instinctively and turned our eyes away. The second was the municipal abattoir of Alexandria in Egypt, for once built out in plain view of the railway, with melancholy strings of buffaloes and other cattle waiting their turn in front. Once I walked along the shore of the Mediterranean behind it, not far from the foundations of Cleopatra's palace, but I had to leap across rivulets of blood running down into that poetic sea, and the smell was almost overpowering, so that I never passed that way again. The third slaughterhouse of my experience was, of all places, at Venice. I had secured a gondolier of singular resourcefulness, and after he had exhausted his list of churches and galleries, he brought me through out-of-the-way canals to the Palace of Butchery, and was chagrined when I declined to go in and insisted on being conveyed elsewhere I shall never forget the forbidding look of the place nor the lowing and bellowing of the kine concealed somewhere in its foul recesses. Where are our artists, that they can enjoy and edify themselves in their doges' palaces and academies of belle arti, with such a background to it all, and discuss beauty and colour over a table d'ôte dinner fresh from the shambles? Are they really so much more dainty and civilised than the old doges themselves, who used to feast while the rats gnawed their living captives in the dungeons below-stairs?

But there is a beauty in ugliness (if I may use a Hibernicism) whenever it reveals a wrong, and who shall say that it does not always do so? An evil deed ought to look ugly, and has no business to look anything else. There is no hypocrisy, at any rate, in ugliness, and hypocrisy is the worst sin, because it is the sin of pretended beauty. Ugliness can at least tell the truth, and in the case of the slaughter-house it tells a great truth, which, though we suppress it to the best of our ability, will utter itself louder and louder until we give heed to the fact that in butchering our fellow-animals we are indulging in a totally unnecessary cruelty. That butchery is cruel is so self-evident that it is hardly necessary to dwell upon the fact, and cruelty usually attends the life of the victim from the beginning. On the cattle-ranges of the West the animals are left to themselves all winter, the thermometer often falling to 40 degrees below zero, Fahrenheit, and the herbage being frequently buried in snow. A large number are expected to die from cold and starvation every year. They are transferred for thousands of miles on trains in the dead of winter or in the scorching heats of summer, left for hours and even days without food or water. Finally, at the abattoir they are received by men who have been drilled into machines, who must kill so many creatures to the minute, and who begin the process of skinning before life is extinct. In some cases death must be prolonged to make the meat white. The animal comes to the place of execution, as a rule, in a state of frenzy, and to overcome its resistance the eye must be gouged of the tail twisted till the gristle cracks. It is futile to preach humanity to men engaged in such a trade. You or I, enlisted in such a profession, would act in the same way.

The essential idea of butchery for food is cruel, and you cannot be cruel humanely. "How could you select such a business?" asked a horrified officer of a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, upon his first visit to he stock-yards of Chicago. "We're only doing your dirty work, sir," was the true and silencing reply. It is brutalising work as well as cruel work, and those who create the demand for it are responsible for it. Where, as in rural regions, slaughter is less of a machine-like occupation it is hardly less revolting. I know of nothing more like a human murder than the killing of a pig on a farm, and the long-continued cries of the doomed beast are not unlike those of a terrified child. And here we have, too, that the ugliest ugliness of treachery. The pig, the hen, the turkey, as the case may be, has learned to look upon you as its best friend—the source of unfailing nourishment and care. And then, some fine day you come, not with the ground-meal or the water-pail, but with axe or knife, and with inexorable fate upon your countenance. What reason our domestic animals have for despising the human race! And with strange perversity we pick out the most inoffensive animals for slaughter. There might be an element of justice in preying upon beasts of prey, but we prefer to slay the harmless deer and cow and sheep. Is carnivorous flesh offensive? Then, why do we make our own flesh offensive by being carnivorous?

There can be but one justification for this consistent, all-round horror of butchery, and that is its necessity. But here again its apologists have no sure foundation to stand on. So far from being a necessary food for man, flesh is a poor food, and first of all it is not a clean food. The bodies of all living animals, including fish and fowl, are continually wearing out and being replenished. The tissue and every part of it, is constantly wasting away, and this waste material, varying in its degrees of nastiness, is conveyed out of the body by divers channels of exit, where it is known as excrement, urine, perspiration, and the like. Take a given cubic inch of flesh. It is full of waste tissue and refuse matter ready for its journey outward or already embarked upon it. If the animal had lived another hour, we should have been able to recognise it as urine or sweat, but we do not recognise it, and we consume it! And this is the case with healthy, robust animals; but very few domestic animals are healthy and robust. The fright of the slaughter-house taints the blood of the healthy ones, but such healthy ones are rare. Tuberculosis rages in the most carefully guarded herds of cattle, and the recent Royal Commission in England has reported that the disease may be communicated to men by the meat. Anthrax, a sudden, mysterious disease which carries off a steer in a few hours, is very infectious to man, and how often may the animal have been slaughtered a few minutes before the attack! It is the interest of the breeder to hurry away his diseased stock to market as fast as possible, and no inspection can overtake his eagerness. Sheep are exceedingly unhealthy for the most part. I visited a flock in winter, and noticed that every individual was suffering most disgustingly from influenza of some kind. I questioned the shepherd, and he assured me that sheep were always that way in winter. Allowing for exaggeration, this is not cheering news for the amateur of mutton-chops. As for pork and ham, there is no such thing as a healthy pig. He suffers from every conceivable kind of disease, many of them human diseases, too; and our very word "scrofula" comes from the Latin scrofa, a sow. And yet we continue to eat them, tuberculosis, scrofula, and all, and fear for our lives if we have to go a day or two without!

We are much more careful of our own cleanliness than of that of our domestic animals, and yet how many of your friends are there whom on this score alone you would be willing to eat? I am quite sure that if we were cannibals we should insist on eating people whom we had not known. And yet when it is a matter of the less educated and dirtier animals, we are ready to swallow the first-comer without asking any questions! And there is no scientific difference between dead bodies. The body, after death, whether it be that of a man or ox or dog, is a corpse, and nothing but a corpse, and we feel instinctively that a corpse is unclean. And it is a true instinct, for decay sets in at once. Yet so lost to shame are we that epicures refuse to eat certain kinds of dead animals unless their rottenness is perceptible to the nose! And so it is that we invariably shrink from corpses except when we eat them!

And the uncleanliness of meat-eating is not confined to the table. It befouls the kitchen too. Almost all that is perilous to cleanliness in the preparation of food in the household is connected with meat; and, with flesh, fish, and fowl once banished, a vast advance towards neatness and purity would be assured in the externals of life. Then, as we have seen, the butcher's trade is a filthy one, and the raising of certain domestic animals, and especially the pig, is not the most tidy of occupations. And so, from their entry into life to the passing away of their remains in the swill-pail, filthiness is wont to accompany the animals on which men prey.

Secondly, in close connection with the uncleanliness of animal food we may consider its unwholesomeness. These waste products of the tissues to which I have referred are poisonous to us, and they usually take the form of uric acid. We have already our own waste-tissues, our own uric acid, to dispose of, and when we add to this poison of our own production the poisons produced by the animals we eat, we increase enormously the labours of our kidneys and digestive organs. Bright' s disease, gout, rheumatism, and many kinds of dyspepsia, with their resultant organic complaints, are caused in this way, and that, too, when the animal food is perfectly healthy. When it is impregnated with tubercles, trichinæ, tape-worm, scrofula, no one knows what the consequence may be, and how far the poisons survive the ordeal of ordinary cooking. Oysters are known to communicate typhoid fever, and ptomaine poisons are much commoner in animal foods than in any other; and the regular readers of our medical Press will find that the list of diseases ascribed to such a diet is continually growing. Doctors, as a rule, with that conservatism which always marks professional opinion, laugh at vegetarianism, but, without being conscious of it, they are fast advancing in that direction. Dr. Chauvel, Medical Inspector of the French Army, has recently made a study of appendicitis among the troops, and he comes to the conclusion that it is caused by meat-eating. Regiments in Algiers, where little meat is eaten, have few cases, and the number increases elsewhere as the habit of eating meat increases. "The carnal régime, then, the abuse of meat, appears to be the true cause of the evil; no meat, no appendicitis," says the Paris Matin, discussing this report. Recent medical investigations into the cause of leprosy attribute it to the eating of tainted fish, and it is well known that scurvy arises from similar animal sources. It is not unlikely that before long cancer may be traced to the same origin.

I have before me two brochures by one of the leading orthodox medical practitioners of New York, and an opponent of vegetarianism, which show the drift against flesh food and the growing belief in its unwholesomeness. One of them is on the subject of rheumatism in childhood. In it the writer absolutely forbids the eating of meat, and prescribes a diet of cereals, vegetables, and fruit. Mineral waters and drugs are useless as a cure, he declares, and "animal broths are totally destitute of food properties." The curative elements are sodium and potassium, each in organic combination as produced by nature. "Vegetable food contains three to four times as much potassium as animal food." "Sodium compounds are largely formed by oxidation of vegetable acids."

The other pamphlet is on the food of children, and in it we read: "There is more so-called nervousness, anaemia, rheumatism, valvular disease of the heart, and chorea at the present time in children from an excess of meat and its preparations in the diet than from all other causes combined." The author seems to regard meat simply as a stimulant of the brain and an appetiser. Surely that is a narrow function for the product of such an immense industry as the production of meat, and other stimulants and appetisers might be found, if we need them.

Thirdly, in addition to the uncleanness and unwholesomeness of meat, it is easy to show that it is also an unnatural food for man. If it were a natural food, would you not be willing to go into the first butcher's shop, cut a slice from a carcass, and put it in your mouth? You would not hesitate to do so to any fruit or vegetable. If meat is a natural food, would you feel any repugnance at eating dog-flesh or cat-flesh merely because you are not accustomed to it? You would rather like to taste a new fruit. Dogs are raised for food in Korea, and there is no difference between their flesh and other meat in principle. Put a kitten and a chick in the same room, and the former will show what its natural food is by pouncing upon the latter and devouring it. Put a baby, of sufficient discretion not to poke pins and needles into its mouth, in the place of the kitten, and it will not attempt to eat the chick; but it will try to eat an apple, which is its natural food. It is a common experience of vegetarians that after years of abstention from flesh foods the idea of eating them becomes disagreeable. I have not eaten meat for six or seven years, and I would not trust myself now to eat a juicy beef-steak in company. A member of a vegetarian colony near St. Louis told me that his children first tasted meat when they were over sixteen years old, and that it made them sick. All of which goes to show that meat is not man's natural food. The structure of his body confirms this belief. He has the long intestines of the graminivorous animals, and not the short intestines of the carnivora. His jaws are hung so that they can grind upon each other, like those of the horse, cow, and camel, and are not fixed vertically like the dog's. He has no carnivorous teeth, those to which that name is often given—the eye-teeth—being much more pronounced in the non-carnivorous anthropoid ape. Richard Owen, the great anatomist and natural historian, said long ago that "the anthropoids and all the quadrumana derive their alimentation from fruits, grains, and other succulent vegetal substances, and the strict analogy between the structure of these animals and that of man clearly demonstrates his frugivorous nature," and this truth is more firmty established to-day than it was when he wrote. It is not natural to eat meat, and we cook it and season it for the express purpose of disguising it. It is not possible to decide positively how man came to adopt an unnatural food, but it is the opinion of the best scientific writers that he may have felt himself forced to it during the Glacial Period, and the disappearance beneath snow and ice of other sources of food-supply. It is unnatural to bury the dead in our stomachs. A vegetarian friend of mine received a present of a brace of grouse one August from an ill-informed acquaintance. In his letter of thanks he advised the donor that he had interred them decorously in his back-yard, and this course seems to me the more natural.

Against this unclean, unwholesome, unnatural diet of meat let us set the vegetable kingdom. If the animal world is unclean and polluting, so is the vegetable world clean and cleansing. What are the excreta of tree and plant? What but the perfume of the flower and the aroma of the forest? And animal filth only makes them flourish the more and smell the sweeter. It almost seems as if the main object of plant-life on earth were to clean up the mess made by animal life. The chemistry of plants, too, seems, contrary to expectation, to be much more perfect than that of the animal. Ducks that feed on fish taste of fish. Milk is redolent of the wild onions eaten by the cow. I have been told on good authority that the eggs of a hen allowed to feed too much on the dunghill will taste of it. Plants, on the other hand, almost invariably disguise their food beyond recognition, and the strawberry or mushroom grown in manure will not disclose a trace of it. Cut into a tree or plant, and you will find all sweet and clean. There are no disgusting secrets as there are in every animal, healthy though he be. And vegetable products do not begin to decay as soon as severed from the parent stock. A seed will keep its vitality for years, and a potato or apple will last all winter. It is not necessary to eat them during their decay. And vegetable decay is different from animal decay. Watch a forest tree from the moment it is felled until it crumbles into dust, and not one disagreeable odour will come from it during that whole period. Whenever there is anything loathsome about a tree it comes from animal—that is, from insect—life. A rotten potato or cabbage is not a pleasant thing, I admit, but it is pure in comparison with any decaying animal body whatever. That vegetable food, including fruit and cereals is wholesome food is pretty generally admitted. Plants may have diseases, but none that human beings can catch from them. There are poisonous plants, but it is easy to avoid them. That vegetable food is natural to us is shown by our unsophisticated tastes and bodily structure. Such food, then, is, unlike animal food, clean, wholesome, and natural.

That vegetable food forms a perfect substitute for animal food results from the fact that it contains all the useful elements of meat in a form easily assimilated. The valuable part of meat is its nitrogenous or albuminous matter, known also as proteids. In the essay on food for children, from which I have already quoted, the author says: "The proteids may be divided into those of animal and those of vegetable origin. There does not appear to be any essential difference between these two classes. Vegetable proteid is equal in nutritive value to animal proteid." And again: "Of the nitrogenous matter in beef, only 5 or 6 per cent. is in the form of proteid, and therefore available for the two main purposes of food—tissue building, and the production of heat and energy and work." He shows, too, that blood-colouring matter (and hence rosy cheeks) comes from vegetable-colouring matter, and not from meat. A meat diet free from vegetables produces pallor. The cereals, such as oatmeal, whole-wheat flour, and the meal of Indian corn (maize) supply proteids more efficiently than meat, and without the poisonous waste-products of meat. The same is true of beans, peas, and lentils, known as legumes, a most nutritious kind of food. Nuts of all kinds, including the pea-nut, which is not properly a nut, contain more available proteid than meat. And eggs and cheese—particularly cheese—are complete substitutes for all that is good in meat, if such animal food is to be taken.

We must have proteids; the only question is, Where shall we get them? If we take them from the ox or the sheep, they got them originally from the vegetable world, and what good does it do us to receive them after they have travelled through the infirm bodies of these animals? From the point of view of economy it is foolish, for the field that will feed several families with wheat will scarcely suffice for a single heifer. It is better to take our proteids direct from plant-life than to receive them at second hand from a Quadruped; and experiments show that in plant form they are soluble much more readily in the gastric juice than in animal form. The proverbial wisdom of our own language has preserved the truth for us. Bread is the staff of life, and not meat.

The proofs that a non-flesh diet is quite as good as a flesh diet are plentiful. The races which eat little or no meat are stronger than those which eat much. The Japanese, Chinese, and Hindoos, whose staple food is rice, can perform feats of strength and endurance which no European could rival; and the European peasant who rarely eats meat is stronger than the man of the higher classes who frequently does. I have heard the story of a spectator watching the unloading of an Indian merchantman in the Thames. Four able-bodied men tottered along the quay with a huge chest between them. "I saw one man, a Hindoo, carry that chest aboard at Calcutta, said the captain. I have seen fellahin in Egypt carrying the trunks of tourists across a narrow bit of desert where two railways failed to connect, two or three great trunks strapped to the back, bent double, of a single man, in a way that would take away an Anglo-Saxon porter's breath to look at it. Lafcadio Hearn tells us that the average Japanese can walk fifty miles a day without becoming tired. Although there is a mere handful of vegetarians in Europe, they are already gathering in far more than their share of athletic honours. The great walking match from Berlin to Vienna in 1893 was won by two vegetarians—Herr Elsasser and Herr Pietz—and the fastest meat-eater was twenty-two hours behind them. Karl Mann, another vegetarian, won a similar race in 1902 from Dresden to Berlin. There were thirty-two competitors, seventeen of whom were vegetarians. The first six who finished were vegetarians. Only thirteen completed the race, and of these ten were vegetarians. One of the best-known amateur athletes in England, Mr. Eustace Miles, frequent holder of the Amateur Tennis Championship and Amateur Racket Championship, in England, America, and Canada, never touches flesh, fish, or fowl, and is a writer on the subject of diet. Vegetarian cyclists have also made an excellent showing.

There are two kinds of objectors to vegetarianism—those who say, "Oh, of course it is all well enough for men who lead a sedentary life in study or office, but it would never do for manual labourers"; and those others who say, "To be sure, it may be good enough for a man who works with his hands, but it is quite out of the question for brain-work." These two classes may be allowed to answer each other. As a matter of fact, the greater number of those who are taking part in the vegetarian movement are brain-workers, and I have not found one who felt any diminution of brain energy, and many (some of whom have eaten no meat for fifty years) who claim that their mental powers have increased since they changed their diet. As for athletics, we have the testimony of many physical culturists and health reformers in Germany, Great Britain, and America. And we all know that when men are in training for athletic contests it is customary to cut down to very small proportions the allowance of meat.

As to the effect of a vegetarian diet, we may reason by analogy from the animals. The strongest animals are vegetarian—the horse, the ox, the camel, the reindeer, and the elephant. In power and endurance the lion and tiger are no match for them, for the strength of the carnivora as a rule shows itself only in short efforts. The longest-lived of the mammals are vegetarian, the elephant living to an age of a hundred years. The swiftest of the mammals are also vegetarian—the deer and antelope and hare. And so is the most prolific—the rabbit—and the most intelligent—the elephant and ape. The dog is the only carnivorous animal who could contest the primacy under any of these heads, and meat keeps him alive for a very few years only; and we always pity a dog who is forced to do hard work, as in Belgium or among the Esquimaux.

The experiments conducted at Yale University in 1903 and 1904 by Professor Chittenden, with the assistance of the United States Government, show that man thrives in every respect upon less than 50 per cent, of the minimum allowance of proteids theretofore believed necessary. The chief feature of these tests, applied for months to soldiers, athletes, and professors, was the reduction almost to the vanishing point of the meat ration. We all eat too much, and meat seems to act as an appetiser, making us eat more than is good for us. I have read a learned argument written by the editor of a leading medical review, in which he admits that a meatless diet will furnish all the necessary proteids, but holds that in order to obtain them we must eat a vastly larger quantity of food, containing an excess of starch, which is harmful and produces obesity. This is a fair example of an argument formed a priori in the study and without any observation of actual results; for the fact is that just the contrary is the case. It is a common experience of vegetarians that, after dropping meat from their bill of fare, they eat much less in total quantity than before, and usually their weight diminishes slightly, if they are inclined to corpulence. My own case is typical. I relish my food fully, but almost everyone I dine with remarks how little I eat; and since adopting a vegetarian diet (including eggs and dairy products) my weight has fallen off a dozen pounds, and now tips the beam at about 13 stone. Meat appears to stimulate the appetite of people who already are overloading their stomachs.

There are certain superficial objections to vegetarianism which are always brought forward and which require an answer. What will become of us if we do not kill animals? some say. The world will become crowded with them, and they conjure up a picture of cities packed with sheep or deer, or a countryside overflowing with cows. As far as the domestic animals now raised for food are concerned, it is hardly necessary to say that we deliberately breed them, and that when we cease to breed them they will cease to perpetuate themselves. As for the wild animals, such as become a nuisance will still have to be killed. Vegetarians do not pretend that men can live altogether without taking life. But it is One thing to kill only those animals that invade our property and disturb our comfort—such as rats and potato-beetles and rabbits—and deliberately to breed animals to be slaughtered and eaten—in others words, to raise corpses. And when we are forced reluctantly to kill animals who interfere with us, we are not obliged to eat them. We do not eat the rats (except in China). Why, then, eat the rabbits?

But, our interlocutor exclaims, "What will you do for boots and shoes?" and he thinks that is unanswerable. Now, the fact is that if there is one thing in our civilisation more odious than butchery, it is our footwear. It is an additional crime of flesh-eating that it condemns us to the use of its by-products to cripple, deform, befoul, and enfeeble our feet. What would our hands be like if we carried them about in leather boxes? The foot should be as presentable as the hand, as healthy, sun-burned, and almost as pliable. It needs the purifying access of the air and the stimulating effects of the outdoor cold and heat. Instead of allowing it this freedom, we shut it up in a stiff, foul, unventilated prison, where its clammy pallor suggests vegetables that sprout in a dark cellar. We bind the toes together, and doom them to atrophy, until a foot is a thing to weep over. Happy the day when there will be no more leather for boots! We shudder at the Chinese lady's foot, while our own art not so very different from hers after all. As for such covering of the feat as the extreme cold of winter and the hardness of roads may actually necessitate, there are plenty of substitutes for leather. The Chinaman prefers his shoes to ours, and he gets on well enough without cowhide.

"But would you exterminate our domestic animals?" our critics continues; and there are tears in his voice for these dear animals whom he eats. Yes, I most assuredly would, in the case of all those which we raise solely for the table. And what are these precious animals that we should lament their disappearance? There is the cow first of all, an animal which we raise by careful selection on account of the size of its udder. Conceive of doing the same thing with any other female animal—the dog or cat or horse—and you will see what a monstrosity the prize cow is. The sooner such a distortion of animalhood passes away the better. And how is it with sheep? The wild sheep, like the chamois and wild goat, is a swift, alert, discerning creature, full of life and alacrity. We demoralise him until after generations of human companionship he hardly knows his head from his tail, and moves about in idiotic masses with about as much intelligence as a globule of quicksilver on a table. Sheep are silly, indeed, but we have made them so. We can continue to raise them for wool, if we will, but that does not oblige us to eat them. We do not eat silkworms. Nor would we have much reason to deplore the departure of the domestic pig. In his wild state as a boar he is a lean, self-respecting animal, and as clean as the average quadruped. It is only after associating with men that he makes a hog of himself. We might well dispense with him and with all the other animals which we raise for food. Their loss would be nothing to deplore.

And so we see that really there !s very little to be said in favour of eating flesh, fish, and fowl, and almost everything to be said against it. I have endeavoured to bring forward no argument that was not sound, for the temptation of the advocates of every reform is to claim too much and vegetarians are no exception to this rule. They will tell you that abstention from meat will cure all diseases. It will not. I once angered a vegetarian orator, who was proceeding on this line, by reminding him that even such good vegetarians as horses and cows were sometimes ill. They will assure you that a vegetarian diet will make a bad man good. It will not. I doubt if it has any effect upon a man's morals except by removing the degrading environment of butchery and ravin. It is true that the most famous of American haunts of vice is known as the "Tenderloin" of New York, and that the name of "joints," applied to less fashionable abodes of evil, is suggestive of flesh-pots; but I am inclined to think that these apparent links between meat-eating and sin are accidental, and that the only wrong of that practice is the direct one of unnatural cruelty and unhygienic and unaesthetic taste. But surely this is enough.

To inflict useless pain, as in the butcher's trade—actually to take pleasure in it, as in the sportsman's—these are clearly inhuman and inhumane habits, the survivals of barbarous ages. It is a superstition, a fetish, that makes us continue such savage customs, just as slavery and the stake and instruments of torture survived long after men should have known better. Every age before us has had its barbarisms—we admit that—and we may be pretty sure that our age has its barbarisms too; and if so, is there one more evident, one which has less to say for itself, than this habit of eating flesh and blood? And from every point of view the lines of reform converge upon a non-flesh diet: from the point of view of health, cleanliness, and an undefiled instinct; from the point of view of humanity and kindness to our animal kin; from the point of view of the artist and votary of beauty; from the point of view of the economist, who fears the pressure of population upon subsistence.

There is a profound philosophy in the suggested change, too. It is no materialistic move, prompted by a sentimental dislike of death and its accompaniments. It is rather the recognition of the relationship between man and all that lives and suffers and feels—a reassertion of the obligation of love to neighbour, with that term extended to take in all the sentient creation. Two thousand years ago, in answer to the question "Who is my neighbour?" the beautiful parable of the Good Samaritan was told, to show that a despised foreigner and heretic was also a brother. You may remember that this philanthropic man, so much kinder than priest and Levite, dressed the wounds of the highwayman's victim, set him on his "beast," brought him to an inn, and took care of him. The part which the "beast" played in this labour of rescue has been generally overlooked, but surely it was the part of a neighbour too; and it is for the neighbourly treatment of the animals whose services we claim that vegetarianism stands, as well as for a clean and wholesome diet.

And now a word of practical advice to those who may feel inclined to experiment in the direction indicated. It is well to do things gradually; not that a sudden change need cause any trouble, but you would probably expect it to, and your expectations might make you imagine that it had. Begin by eating meat only once a day; then, after a month or two, drop it altogether, but still eat fish for a time. Take care meanwhile to substitute the foods rich in proteids—the cereals , whole-wheat bread, peas and beans, cheese and eggs. Eventually it may be best to drop eggs and dairy products

too, but it is difficult to do it if you live with others, and I have not yet been able in my own case. It is a very easy change to make, to give up meat. If you have plenty of other food, you will not feel any deprivation at all. I know what it is to have given up tobacco, and it was a serious struggle, and I blame no one for failing in the attempt, but I have never had the slightest inclination to go back to meat; and the idea is now disagreeable, and the smell of a butcher's-shop or of a kitchen where bacon is frying is most offensive to me. It is because the change is so easy that I cannot believe the doctors are right in calling meat a stimulant. No real stimulant can be given up with such facility. As for the deterring influences of your friends and relations, nothing worth while can be done in the world without rising superior to that. I remember that when, ten years ago, I told Count Tolstoy at Yasnaia Poliana

that I intended to try vegetarianism, he answered, "Your wife will be sure to object." But, prophet that he is, his prediction was false, and difficulties of environment become small or disappear when they are once faced.

It is a part of the business of man to mould his environment, and help to create the environment of posterity; and even in the case of our own bodies, if after so many years of a mistaken diet it proved to be difficult to return to the right path, it would still be our duty to make the attempt. It is little short of miraculous that the return should be so easy. Ages ago, and before the historical period, our ancestors rose from a condition of cannibalism, and doubtless the medicine-men of the time took the conservative side, and they really had a good deal to say for themselves. Men had always been cannibals, and in some respects the devouring of an enemy slain in battle is less shocking than the eating of a pet lamb or a family cow. But the reform made its way notwithstanding, and if I am not mistaken, we are bound just as surely to advance beyond the system of quasi-cannibalism in which we live, and which has no justification except the fact that it has always existed.

ON VEGETARIANISM.

By Elisée Reclus.

Men of such high standing in hygiene and biology having made a profound study of questions relating to normal food, I shall take good care not to display my incompetence by expressing an opinion as to animal and vegetable nourishment. Let the cobbler stick to his last. As I am neither chemist nor doctor, I shall not mention either azote or albumen, nor reproduce the formulas of analysts, but shall content myself simply with giving my own personal impressions, which, at all events, coincide with those of many vegetarians. I shall move within the circle of my own experiences, stopping here and there to set down some observation suggested by the petty incidents of life.

First of all I should say that the search for truth had nothing to do with the early impressions which made me a potential vegetarian while still a small boy wearing baby-frocks. I have a distinct remembrance of horror at the sight of blood. One of the family had sent me, plate in hand, to the village butcher, with the injunction to bring back some gory fragment or other. In all innocence I set out cheerfully to do as I was bid, and entered the yard where the slaughtermen were. I still remember this gloomy yard where terrifying men went to and fro with great knives, which they wiped on blood-besprinkled smocks. Hanging from a porch an enormous carcase seemed to me to occupy an extraordinary amount of space; from its white flesh a reddish liquid was trickling into the gutters. Trembling and silent I stood in this blood-stained yard incapable of going forward and too much terrified to run away. I do not know what happened to me; it has passed from my memory. I seem to have heard that I fainted, and that the kind-hearted butcher carried me into his own house; I did not weigh more than one of those lambs he slaughtered every morning.

Other pictures cast their shadows over my childish years, and, like that glimpse of the slaughter-house, mark so many epochs in my life. I can see the sow belonging to some peasants, amateur butchers, and therefore all the more cruel. I remember one of them bleeding the animal slowly, so that the blood fell drop by drop; for, in order to make really good black puddings, it appears essential that the victim should have suffered proportionately. She cried without ceasing, now and then uttering groans and sounds of despair almost human; it seemed like listening to a child.

And in fact the domesticated pig is for a year or so a child of the house; pampered that he may grow fat, and returning a sincere affection for all the care lavished on him, which has but one aim—so many inches of bacon. But when the affection is reciprocated by the good woman who takes care of the pig, fondling him and speaking in terms of endearment to him, is she not considered ridiculous—as if it were absurd, even degrading, to love an animal that loves us?

One of the strongest impressions of my childhood is that of having witnessed one of those rural dramas, the forcible killing of a pig by a party of villagers in revolt against a dear old woman who would not consent to the murder of her fat friend. The village crowd burst into the pigstye and dragged the beast to the slaughter place where all the apparatus for the deed stood waiting, whilst the unhappy dame sank down upon a stool weeping quiet tears. I stood beside her and saw those tears without knowing whether I should sympathise with her grief, or think with the crowd that the killing of the pig was just, legitimate, decreed by commense sense as well as by destiny.

Each of us, especially those who have lived in a provincial spot, far away from vulgar ordinary towns, where everything is methodically classed and disguised—each of us has seen something of these barbarous acts committed by flesh-eaters against the beasts they eat. There is no need to go into some Porcopolis of North America, or into a saladera of La Plata, to contemplate the horrors of the massacres which constitute the primary condition of our daily food. But these impressions wear off in time; they yield before the baneful influence of daily education, which tends to drive the individual towards mediocrity, and takes out of him anything that goes to the making of an original personality. Parents, teachers, official or friendly, doctors, not to speak of the powerful individual whom we call "everybody," all work together to harden the character of the child with respect to this "four-footed food," which, nevertheless, loves as we do, feels as we do, and, under our influence, progresses or retrogresses as we do.

It is just one of the sorriest results of our flesh-eating habits that the animals sacrificed to man's appetite have been systematically and methodically made hideous, shapeless, and debased in intelligence and moral worth. The name even of the animal into which the boar has been transformed is used as the grossest of insults; the mass of flesh we see wallowing in noisome pools is so loathsome to look at that we agree to avoid all similarity of name between the beast and the dishes we make out of it. What a difference there is between the moufflon's appearance and habits as he skips about upon the mountain rocks, and that of the sheep which has lost all individual initiative and becomes mere debased flesh—so timid that it dares not leave the flock, running headlong into the jaws of the dog that pursues it. A similar degradation has befallen the ox, whom now-a-days we see moving with difficulty in the pastures, transformed by stock-breeders into an enormous ambulating mass of geometrical forms, as if designed beforehand for the knife of the butcher. And it is to the production of such monstrosities we apply the term "breeding"! This is how man fulfils his mission as educator with respect to his brethren, the animals.

For the matter of that, do we not act in like manner towards all Nature? Turn loose a pack of engineers into a charming valley, in the midst of fields and trees, or on the banks of some beautiful river, and you will soon see what they would do. They would do everything in their power to put their own work in evidence, and to mask Nature under their heaps of broken stones and coal. All of them would be proud, at least, to see their locomotives streaking the sky with a network of dirty yellow or black smoke. Sometimes these engineers even take it upon themselves to improve Nature. Thus, when the Belgian artists protested recently to the Minister of Railroads against his desecration of the most beautiful parts of the Meuse by blowing up the picturesque rocks along its banks, the Minister hastened to assure them that henceforth they should have nothing to complain about, as he would pledge himself to build all the new workshops with Gothic turrets!

In a similar spirit the butchers display before the eyes of the public, even in the most frequented streets, disjointed carcases, gory lumps of meat, and think to conciliate our aestheticism by boldly decorating the flesh they hang out with garlands of roses!

When reading the papers, one wonders if all the atrocities of the war in China[1] are not a bad dream instead of a lamentable reality. How can it be that men having had the happiness of being caressed by their mother, and taught in school the words "justice" and "kindness," how can it be that these wild beasts with human faces takes pleasure in tying Chinese together by their garments and their pigtails before throwing them into a river? How is it that they kill off the wounded, and make the prisoners dig their own graves before shooting them? And who are these frightful assassins? They are men like ourselves, who study and read as we do, who have brothers, friends, a wife or a sweetheart; sooner or later we run the chance of meeting them, of taking them by the hand without seeing any traces of blood there.

But is there not some direct relation of cause and effect between the food of these executioners, who call themselves "agents of civilisation," and their ferocious deeds? They, too, are in the habit of praising the bleeding flesh as a generator of health, strength, and intelligence. They, too, enter without repugnance the slaughter-house, where the pavement is red and slippery, and where one breathes the sickly sweet odour of blood. Is there then so much difference between the dead body of a bullock and that of a man? The dissevered limbs, the entrails mingling one with the other, are very much alike: the slaughter of the first makes easy the murder of the second, especially when a leader's order rings out, or from afar comes the word of the crowned master, "Be pitiless."

A French proverb says that "every bad case can be defended." This saying had a certain amount of truth in it so long as the soldiers of each nation committed their barbarities separately, for the atrocities attributed to them could afterwards be put down to jealousy and national hatred. But in China, now, the Russians, French, English, and Germans have not the modesty to attempt to screen each other. Eyewitnesses, and even the authors themselves, have sent us information in every language, some cynically, and others with reserve. The truth is no longer denied, but a new morality has been created to explain it. This morality says there are two laws for mankind, one applies to the yellow races and the other is the privilege of the white. To assassinate or torture the first named is, it seems, henceforth permissible, whilst it is wrong to do so to the second.

Is not our morality, as applied to animals, equally elastic? Harking on dogs to tear a fox to pieces teaches a gentleman how to make his men pursue the fugitive Chinese. The two kinds of hunt belong to one and the same "sport"; only, when the victim is a man, the excitement and pleasure are probably all the keener. Need we ask the opinion of him who recently invoked the name of Attila, quoting this monster as a model for his soldiers?

It is not a digression to mention the horrors of war in connection with the massacre of cattle and carnivorous banquets. The diet of individuals corresponds closely to their manners. Blood demands blood. On this point any one who searches among his recollections of the people whom he has known will find there can be no possible doubt as to the contrast which exists between vegetarians and coarse eaters of flesh—greedy drinkers of blood—in amenity of manner, gentleness of disposition and regularity of life.

It is true these are qualities not highly esteemed by those "superior persons," who, without being in any way better than other mortals, are always more arrogant, and imagine they add to their own importance by depreciating the humble and exalting the strong. According to them, mildness signifies feebleness: the sick are only in the way, and it would be a charity to get rid of them. If they are not killed, they should at least be allowed to die. But it is just these delicate people who resist disease better than the robust. Full-blooded and high-coloured men are not always those who live longest: the really strong are not necessarily those who carry their strength on the surface, in a ruddy complexion, distended muscle, or a sleek and oily stoutness. Statistics could give us positive information on this point, and would have done so already, but for the numerous interested persons who devote so much time to grouping, in battle array, figures, whether true or false, to defend their respective theories.

But, however this may be, we say simply that, for the great majority of vegetarians, the question is not whether their biceps and triceps are more solid than those of the flesh-eaters, nor whether their organism is better able to resist the risks of life and the chances of death, which is even more important: for them the important point is the recognition of the bond of affection and goodwill that links man to the so-called lower animals, and the extension to these our brothers of the sentiment which has already put a stop to cannibalism among men. The reasons which might be pleaded by anthropophagists against the disuse of human flesh in their customary diet would be as well-founded as those urged by ordinary flesh-eaters to-day. The arguments that were opposed to that monstrous habit are precisely those we vegetarians employ now. The horse and the cow, the rabbit and the cat, the deer and the hare, the pheasant and the lark, please us better as friends than as meat. We wish to preserve them either as respected fellow-workers, or simply as companions in the joy of life and friendship.

"But," you will say, "if you abstain from the flesh of animals, other flesh-eaters, men or beasts, will eat them instead of you, or else hunger and the elements will combine to destroy them." Without doubt the balance of the species will be maintained, as formerly, in conformity with the chances of life and the inter-struggle of appetites; but at least in the conflict of the races the profession of destroyer shall not be ours. We will so deal with the part of the earth which belongs to us as to make it as pleasant as possible, not only for ourselves, but also for the beasts of our household. We shall take up seriously the educational role which has been claimed by man since prehistoric times. Our share of responsibility in the transformation of the existing order of things does not extend beyond ourselves and our immediate neighbourhood. If we do but little, this little will at least be our work.

One thing is certain, that if we held the chimerical idea of pushing the practice of our theory to its ultimate and logical consequences, without caring for considerations of another kind, we should fall into simple absurdity. In this respect the principle of vegetarianism does not differ from any other principle; it must be suited to the ordinary conditions of life. It is clear that we have no intention of subordinating all our practices and actions, of every hour and every minute, to a respect for the life of the infinitely little; we shall not let ourselves die of hunger and thirst, like some Buddhist, when the microscope has shown us a drop of water swarming with animalculæ. We shall not hesitate now and then to cut ourselves a stick in the forest, or to pick a flower in a garden; we shall even go so far as to take a lettuce, or cut cabbages and asparagus for our food, although we fully recognise the life in the plant as well as in animals. But it is not for us to found a new religion, and to hamper ourselves with a fectarian dogma; it is a question of making our existence as beautiful as possible, and in harmony, so far as in us lies, with the aesthetic conditions of our surroundings.

Just as our ancestors, becoming disgusted with eating their fellow-creatures, one fine day left off serving them up to their tables; just as now, among flesheaters, there are many who refuse to eat the flesh of man's noble companion, the horse, or of our fireside pets, the dog and cat—so is it distasteful to us to drink the blood and chew the muscle of the ox, whose labour no longer want to hear helps to grow our corn. We no longer want to hear the bleating of sheep, the bellowing of bullocks, the groans and piercing shrieks of the pigs, as they are led to the slaughter. We aspire to the time when we shall not have to walk swiftly to shorten that hideous minute of passing the haunts of butchery with their rivulets of blood and rows of sharp hooks, whereon carcases are hung up by blood-stained men, armed with horrible knives. We want some day to live in a city where we shall no longer see butchers' shops full of dead bodies side by side with drapers' or jewellers', and facing a druggist's, or hard by a window filled with choice fruits, or with beautiful books, engravings or statuettes, and works of art. We want an environment pleasant to the eye and in harmony with beauty.

And since physiologists, or better still, since our own experience tells us that these ugly joints of meat are not a form of nutrition necessary for our existence, we put aside all these hideous foods which our ancestors found agreeable, and the majority of our contemporaries still enjoy. We hope before long that flesh-eaters will at least have the politeness to hide their food. Slaughter houses are relegated to distant suburbs; let the butchers' shops be placed there too, where, like stables, they shall be concealed in obscure corners.

It is on account of the ugliness of it that we also abhor vivisection and all dangerous experiments, except when they are practised by the man of science on his own person. It is the ugliness of the deed which fills us with disgust when we see a naturalist pinning live butterflies into his box, or destroying an ant-hill in order to count the ants. We turn with dislike from the engineer who robs Nature of her beauty by imprisoning a cascade in conduit-pipes, and from the Californian woodsman who cuts down a tree, four thousand years and three hundred feet high, to show its rings at fairs and exhibitions. Ugliness in persons, in deeds, in life, in surrounding Nature—this is our worst foe. Let us become beautiful ourselves, and let our life be beautiful.

What then are the foods which seem to correspond better with our ideal of beauty both in their nature and in their needful methods of preparation? They are precisely those which from ail time have been appreciated by men of simple life the foods which can do best without the lying artifices of the kitchen. They are eggs, grains, fruits; that is say, the products of animal and vegetable life which represent in their organisms both the temporary arrest of vitality and the concentration of the elements necessary to the formation of new lives. The egg of the animal, the seed of the plant, the fruits of the tree, are the end of an organism which is no more, and the beginning of an organism which does not yet exist. Man gets them for his food without killing the being that provides them, since they are formed at the point of contact between two generations. Do not our men of science who study organic chemistry tell us, too, that the egg of the animal or plant is the best storehouse of every vital element? Omne vivum ex ovo.

FINIS.

![]()

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse

- ↑ Written in 1900.