The Moki snake dance

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1929.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1935, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 88 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse

The Moki Snake Dance

A popular account of that unparalleled

dramatic pagan ceremony of the

Pueblo Indians of Tusayan,

Arizona, with incidental

mention of their life

and customs.

By WALTER HOUGH, Ph. D.

Sixty-four Half-tone Illustrations from

Special Photographs.

Thirty-second Thousand.

Published by the Passenger Department

SANTA FE ROUTE,

1900

|

RACER. |

JUST at the dawn of an August morning groups of eager watchers sit along the precipitous cliffs or slopes of a mesa bearing on its crest a Moki village. All faces are turned in one direction; the gray light becomes many-hued before the near approach of the sun. A murmur passes through the crowd, in the distance a number of dark forms are seen running toward the mesa; nearer they come, pursued by boys and girls with wands of cornstalk, and run up the tortuous trail as though on level ground. As the sun appears above the eastern horizon the winner passes over the roof of the Snake kiva and the day of the Snake dance has begun with the Snake race. The runners deposit the melon vines, corn and other products they have carried from the fields, and the panting victor gets for his prize the glory of winning. As in the Greek games, the Mokis honor the swift runner.

As the day wears on the interest centers in the kivas, where swarthy priests are bringing to a close the mysterious rites begun days before, when the astronomer Sun priest had directed the town crier to announce the commencement of the ceremony. Since that time the priests had descended into the kiva, and a fleet runner had each day carried plumed prayer-sticks to the distant springs and shrines. Four days to the north, west, south and east snakes had been hunted. Then came the Antelope dance on the evening before the Snake dance; the sixteen songs and drama were enacted in the kiva while the Snake race was being run, and the time is now ripe for the final spectacle. The snakes have been washed and placed in jars and the costuming begins. Long-haired, painted priests in scanty attire emerge from the kivas and go on various errands. Visitors and Mokis examine one another with mutual curiosity; the children are having a jolly time, for the Snake dance comes in their village but once in two years, and white visitors are sure to bring candy to put a climax to the stuffing of new corn, melons and other good things of August.

Other dances of the Mokis are more pleasing, as the Kachina dances, with their mirth and music, or the Flute dance, full of color and ceremony, but the Snake dance attracts with a potent fascination. One gets so interested in the progress of the dance that the anticipated element of horror does not appear amid the rhythmic movement and tragic gestures of the dancers with here and there the sinuous undulation of a venomous rattlesnake. Along the sky-line of the houses and on every available foothold and standing place are spectators. At Wolpi, the top of the mushroom-shaped rock is a favorite seat. The crowd is hardly less interesting than the dancers. Everyone, except the white visitor, is in gala costume, Moki and Navajo vying in gaudy colors. The Moki maidens have their hair done up in great whorls of shining blackness at the sides of their heads. The women, who have brushed away the evidences of preparation for the feast to follow the dance, now appear at their best, and the children dash around, consuming unlimited slices of watermelon. Mormons, be-pistoled cowboys, prospectors, army officers, teachers from the schools, scientists, photographers, and tourists in the modern costume suitable for camp life, mingle with the Indian spectators in motley confusion. Not less than one hundred white people witnessed the Snake dance at Wolpi in 1897. Bach year there is a larger attendance.

If the visitor will look around he will see that at one side of the dance plaza there is a bower of green cottonwood branches, the kisi, where the snakes are to be kept in readiness during the dance. The descending sun casts a long shadow eastward from the kisi when a priest enters the plaza with a bag containing the reptiles and quickly disappears among the branches. This is the man who hands the snakes out to the dancers through a small opening in the

|

MOKI CHILDREN. |

|

Copyright 1896, by G. Wharton James. Used by permission |

front of the kisi. The expectancy now is intense. All eyes are fixed in the direction from which the priests will appear. The sun sinks lower and the evening colors steal into the landscape, but no one notices them.

"Here they come!" The grand entry of the Antelope priests causes a sensation. With bare feet, and their semi-nude bodies streaked with white paint; a band of white on the chin from mouth to ear, rattles of tortoise shell tied to the knee, embroidered kilts of white cotton fastened around the loins, necklaces of shell and turquoise, and fox skins hanging behind from the belt, these priests present a startling though not unattractive appearance. At the head of the file comes the Antelope Chief bearing his tiponi or sacred badge across his left arm. Next comes the bearer of the medicine bowl. All the other priests carry a small rattle in either hand. With stately mien, and looking to neither right nor left, the Antelope priests pass four times around the plaza to the left, each sprinkling sacred meal and stamping violently upon the plank in the ground in front of the kisi. The hole in the middle of the plank is the opening into the under-world and the dancers stamp upon it to inform the spirits of their ancestors that a ceremony is in progress. Fortunate is the man who breaks the board with his foot! When the circuit is made, the Antelope priests line up in front of the kisi facing outward; thereis a hush and the Snake priests enter.

The grand entry of the Snake priests is dramatic to the last degree. With majestic strides they hasten into the plaza, every attitude full of energy and fierce determined purpose. The costume of the priests of the sister society of Antelopes is gay in comparison with that of the Snake priests. Their bodies rubbed with red paint, their chins blackened and outlined with a white stripe, their dark red kilts and moccasins, their barbaric ornaments, give the Snake priests a most somber and diabolical appearance. Around the plaza, by a wider circuit than the Antelopes, they go striking the sipapu plank with the foot and fiercely leaping upon it with wild gestures. Four times the circuit is made; then a line is formed facing the line of the Antelopes, who cease shaking their rattles which simulate the warning note of the rattlesnake. A moment's pause and the rattles begin again and a deep humming chant accompanies them. The priests sway from side

FLUTE DANCE, ORAIBI. Higgins, photo

|

SPECTATORS WOLPI. |

All at once the Snake line breaks up into groups of three, composed of the "carrier" and two attendants. The song becomes more animated and the groups dance, or rather hop, around in a circle in front of the kisi, one attendant (the "hugger") placing his arm over the shoulder of the "carrier" and the other (the "gatherer") walking behind. In all this stir and excitement it has been rather difficult to see why the "carrier" dropped on his knees in front of the kisi; a moment later he is seen to rise with a squirming snake, which he places midway in his mouth, and the trio dance around the circle, followed by other trios bearing hideous snakes. The "hugger" waves his feather wand before the snake to attract its attention, but the reptile inquiringly thrusts its head against the "carrier's" breast and cheeks and twists its body into knots and coils. On come the demoniacal groups, to music now deep and resonant and now rising to a frenzied pitch, accompanied by the unceasing sibilant rattles of the Antelope chorus. Four times around and the "carrier" opens his mouth and drops the snake to the ground and the "gatherer" dextrously picks it up, adding in the same manner from time to time other snakes, till he may have quite a bundle composed of rattlesnakes, bull snakes and arrow snakes. The bull snakes are large and showy, and impressive out of proportion to their harmfulness. When all the snakes have been duly danced around the ring, and the nerve tension is at its highest pitch, there is a pause; the old priest advances to an open place and sprinkles sacred meal on the ground, outlining a ring with the six compass points, while the Snake priests gather around. At a given signal the snakes are thrown on the meal drawing and

|

KACHINA DANCERS. |

|

NAVAJO SPECTATOR. |

a wild scramble for them ensues, amid a rain of spittle from the spectators on the walls above. Only an instant and the priests start up, each with one or more snakes; away they dart for the trail to carry the rain-bringing messengers to their native hiding places. They dash down the mesa and reappear far out on the trails below, running like the wind with their grewsome burdens. The Antelope priests next march gravely around the plaza four times, thumping the sunken plank, and file out to their kiva. The ceremony is done.

Stay! there is another scene in this drama which may seem a fitting termination. Whoever wishes may go to look on, but not everyone goes. The Snake priests return, go to the kiva and remove all their trappings, come out to the edge of the cliff where the medicine women have brought great bowls of a dark liquid brewed in secrecy and mystery. No one knows the herbs and spells in this liquid but Salako of Wolpi, the head Snake woman of the Moki pueblos. The priests drink of the medicine; in about forty-five seconds it sees the light of day again. They repeat the operation, and so goes on a scene that beggars description. Even scientific equanimity cannot observe without qualms that this is a purification ceremony, carried out by the priests with the ruthlessness of devotion. This feature of the dance, however, will never become popular. Various explanations of the purpose of the medicine have been current. It has been supposed, among others, to be the antidote for the venom of the rattlesnake. Probably it is only for ceremonial purification; at any rate it is a good preparation for the great feast following the dance.

For this feast come bearing trays fair maidens and trim women of gala bread, well cooked meat, corn pudding and other dainties and substantials in profusion. That night there is feasting and every Moki gets what the cowboys call a "mortal gorge." Next day and the day following the boys and girls have great sport in the pueblos. A young man will take a ribbon, a piece of

|

DANCE ROCK AND KIBI. |

|

MOKI GIRLS. Hillers, photo. |

pottery or any other object and appear on the housetops or street, only to be set upon and chased by the girls bent on securing the prize.

Many questions suggest themselves to everyone who witnesses the Snake dance. Some do not seem to be very easy to answer, and some are those which, perhaps, the wisest and most lore-learned priest cannot answer now after the lapse of centuries since the ceremony began. Still, most of us can leave them for the scientists to pore over. What everyone wants to know

|

CIRCUIT OF ANTELOPE PRIESTS, WOLPI.Vroman, photo. |

large rattlesnakes, which from their age had perhaps been danced around the ring before, coiled together and for a time refused to move, almost breaking up the performance. An experienced snake driver at length succeeded in making them uncoil, when they were easily picked up. This is thought to be the secret of handling the rattlesnake; never to handle him when he is coiled, for it is said that this serpent cannot strike without coiling. Then, too, the snakes may have been somewhat subjugated by their bewildering treatment, since they were dragged from their haunts by naked men armed with hoes and sticks, thrust with other snakes into a bag and brought to the kivas, and afterward washed and uncivilly flung about.

The Snake dance is exciting enough, but the two or three men who have witnessed the sinister rites called "snake washing" in the dark kiva tell a story which makes the blood curdle. Doctor Fewkes relates this experience as follows:

LINE-UP BEFORE KISI, WOLPI.

Copyright, 1896, by G. Wharton James. Used by permission.

FACE VIEW, SNAKE PRIESTS, ORAIBI.

it requires four days of vigilant search to the four points of the compass to procure enough. Some years ago, a Wolpi farmer, while in his cornfield, was bitten on the hand by a rattlesnake, and the combined efforts of the Indian doctors and some white people who happened to be near by were applied for his relief. After a great deal of suffering he recovered. Soon after, the Snake Society informed him that he must become a Snake priest, because he was favored by the rattlesnake. Perhaps Intiwa, for that was his name, did

TRIO OF DANCERS.

not see where the favor came in, but he was duly installed as a member of the Society.

Turning now from this strange, nerve-wrenching scene, which many have crossed the mysterious Painted Desert north of the Little Colorado river to witness, some general account of the Mokis should be interesting. Perched upon high, warm-tinted sandstone mesas, narrow like the decks of great Atlantic liners, are their clustered dwellings, scarcely to be distinguished from the living rock upon which they rest. High up above the plain, viewing from all sides an almost illimitable distance, basking in the brilliant sunshine from sunrise to sunset, bathed in the pure, life-giving air, the Mokis, or "good people,"[2] as they delight to call themselves, must feel freedom in its truest sense. Here is isolation. In the long centuries the Mokis have dwelt here they have had few visitors. The all-venturing Spaniards, in their sixteenth century quest for the mythical doorposts of gold set with jewels, were way-weary long before their toilsome journey brought them to the base of the giant mesas. In this semi-desert, far out of the trail traveled by friends and foes, the Mokis found the desired

seclusion and peace after the harrying of the Apache and Ute, whose hand was against every man.Perhaps the word mysterious as applied to the desert may need explanation to city-dwellers and those who are accustomed to limited horizons. In the desert a new sensation comes to those who have exhausted the repertory of sensations at the end of a rapid century. In the desert the desert is supreme. The sense of freedom and exhilaration, which everyone must feel, is personal; the desert is titanic; gradually it compels awe and wonder. A feeling

of vastness, almost infinity, dawns in the mind with an impression of mystery. Here thousands of square miles stretch in iridescent beauty to the violet horizon or to the velvety blue mountains; nearer stand the strange forms of the volcanic buttes; across the sand plain the purple cloud shadows float, attended by the tawny sand whirlwinds; a distant thunderstorm marches along, dwarfed in all its energy to a small part of the scene. The morning and evening reveal new coloring and beauty beyond the power of pen or pencil to depict. With the night new experiences come in the desert. In the clear air of Tusayan myriads of stars are revealed. It is not often the good fortune of the astronomer to enjoy such skies for observation. Stars of low magnitude, rarely seen elsewhere, are easily found in the night heavens of Tusayan. It may seem like romancing, but it is true, the powdery, misty starlight is strong enough to admit of reading the dial of a watch and to distinguish the outline of mesas and buttes miles away. Then the silence of the night is overpowering. Not a cricket chirps and no animal disturbs the almost oppressive silence.

When the conquistadores came to Tusayan, some three hundred and fifty years ago, they found the Mokis high up on the mesas, but not on the rocky tops where the towns are now built. This meeting of the Conquerors

and the Mokis has always seemed a picturesque subject. The Spaniards recorded their experiences and the Mokis relate the traditions of the experiences of their forefathers passed along by word of mouth, accurate as if written down. Beneath the town then perched on the higher slope of the Wolpi mesa, came a band of horsemen, some clad in armor and warlike trappings badly damaged and battered by wear and tear, but impressive to the Indian, who for the first time saw the white man. Perhaps the Mokis were not very friendly. The warrior priest strode down the trail followed by his band and drew a line of sacred meal across the path to the town, over which, according to immemorial custom, no one might come with impunity. This "dead line" brought death instead to the Mokis. At the fire of the dreadful guns they fled up the narrow trail to refuge. The Spaniards dared not follow up the rocky way, but camped for the night by a spring. In the morning the timorous Mokis came down with presents of food and woven stuffs. This is the first picture of the Mokis of Wolpi, who were thus introduced to the proud Castilian, bent on reaching new lands to despoil. Later came a new company, bringing priests to turn the peaceful people from their native superstitions. When the town of Wolpi burst upon their view it was a new town, built on the highest summit of the mesa! The timid people had moved up from the lower point, taking with them house beams, stones, and every other portion of their dwellings. The trails were rendered inaccessible and the people ascended and descended by a movable ladder. Still they received the priests and submitted to the enforced labor of building a church, carrying, with infinite toil, beams of cottonwood from the Little Colorado. Many of these carved beams now support the roofs of the pagan kivas. Later, when the oppression grew too great, the Mokis committed one of the few overt acts which may be charged against them. They threw the "long gowns," as they called the friars, over the cliffs, and cut loose once for all from the foreign religion. This ended the contact of the whites with the Mokis for long years until, at last, the Government took them under its protection.

But the Moki had immemorial enemies, as has been hinted. The Apache, who centuries ago came out of the high north, a rude and fierce being, incapable of high things, is responsible for the acropolis towns all along the trails by which the Moki clans came to Tusayan. The history of the wanderings of the Moki to this land of scant promise would be interesting if all the threads

Maude, photo.

TIPONI.

breasts of the ancient pueblo dwellers and forced them to forever move on. Ruins without number attest the flux of population over an area in which the countries of the ancients of the Old World would be lost. Still these ruins are not without order; the clans moved along together in those dark ages, so that the ruins are found in groups. Thus if we hark back on the trail by which some of the clans came from the south to Tusayan, the Mogollon Mountains at Chavez Pass will show

two large ruins to which Moki tradition gives the name of "the place of the antelopes." Thirty-two miles to the north is the next stopping place, and the clans must have prospered in the valley of the Little Colorado at Winslow, for here are the ruins of five towns, called by those versed in the lore of the past Homolobi, or "the place of the two views." The grand panorama of the Moki buttes seen from "the place of the antelopes" was still visible from Homolobi, though at a lower viewpoint. Long before the conquistadores came to ravage the New World, the people of Homolobi had abandoned their towns and taken up their weary journey to Tusayan, where now are seven towns of the "good people." It is interesting to find that in Wolpi different clans live in different sections of the town just as they had camped together in the old days, and in the order in which they came from their desert wandering. This journey of some of the clans of Mokis began much farther away than the two faint points on the dim Mogollones where antelopes range to this day. To say that the Mokis belong by language to the great Uto-Aztecan stock means that in bygone times they were in contact with the Aztecs or may even have been a branch of that far-famed people. Just here, if it might be possible to correct

AN ARIZONA CAMP.

the popular hallucination in reference to the Aztecs, it would be well to say that that mysterious and ever-vanishing people were nothing more nor less than American Indians. In some lines of work the Mokis of Homolobi, for instance, were superior to the Aztecs. Romance and the Aztecs have been sadly mixed up by the writers of a past generation.

The towns of Tusayan are seven. Wolpi, "the place of the gap," named for the deep cut across the mesa on which it is built, is best known. The people are very friendly and are more advanced than the other tribes There is a school and many families live below the mesa in red-roofed houses. Perhaps in a few years the old pueblo will be abandoned and the quaint customs forgotten.Next to Wolpi on the east is Si-chom′-ovi, "the mound of flowers," an offshoot of Wolpi—on account of a disagreement, it is thought.

Ha′-no (also known as Te′-wa) is the third village on the First or East Mesa, near the gap. Hano is a village of Tewans who were induced to come from the Rio Grande two centuries ago to assist in defending the peaceful Mokis from the Apaches and Utes. They were located at the head of the easiest trail up the mesa, and on a smooth rock face is an inscription recording a battle in which they vanquished the Utes. These "keepers of the trail" are expert potters, and most of the Moki ware is of their handicraft. It seems strange to find in Tusayan these foreigners still speaking a language different from that of their neighbors.

Seven miles to the west, across the valley from Wolpi, the point of Second or Middle Mesa stands out in silhouette. The first town is called Mi-shong′-inovi, second in size in Tusayan. The Snake dance is held here in odd years, as at Wolpi. At such times the large interior plaza is extremely picturesque. On

CORN CARRIER.

the east trail to Mishonginovi there is a curious hanging rock forming an arch under which the trail passes.

Back of Mishonginovi is the small town of Shi-paul′-ovi, "the place of the peaches," the most picturesquely located of the Moki pueblos, and with the most elevated situation. Shipaulovi is a comparatively modern town, having been formed by families from Shung o′-pavi since the Spaniards introduced peaches. Here the Snake dance is held in even years, alternating with that of the Flute.

Shungopavi, "the place of the reed grass," is a few miles west of Shipaulovi. Reed grass is prescribed for the mats wound around the ceremonial wedding blankets of white cotton. A small country place of Shungopavi is located at Little Burro Spring, some twelve miles south of the town.

MAIL CARRIER.

Oraibi, with its fifty mile distant little offshoot, Mo′′-en-kop′-i, marks the extreme western, as Taos marks the eastern, extent of the pueblo region. Nearly one-half, or about eight hundred, of the Mokis live in Oraibi. The Snake Society at this pueblo, though fewer in numbers than at several of the other towns, gives an interesting performance. The large open plaza where the dance is held offers excellent opportunities for photographing and for viewing the spectacle.

SPINNER.

In the even years visitors to Tusayan may see three Snake dances—those of Oraibi, Shipaulovi, and Shungopavi, unless the dates coincide, which they are unlikely to do.

The Province of Tusayan, where the Mokis now live and thrive, is not a total desert waste, although the first impression of those accustomed to green fields and frequent rains is likely to be to the contrary. Drought-defying plants bloom at certain seasons, and fill wide stretches with color. Along the sandy washes, adjacent to the pueblos, which rarely by the good will of the rain gods show a silver glint of water, are corn fields and melon and bean patches, well cared for and jealously guarded by their owners. Internecine war is waged against the freebooting crows, mice, prairie dogs and insects, and woe betide any four-footed marauder that is caught foraging there; he is soon roasted and supplying protoplasm to the Moki organism; except in case of a burro, when his ears are docked in proportion to the magnitude or incorrigibility of his misdeed, to brand him publicly as a thief.

MOTHER AND CHILD.

On the rocky side of the mesa are thriving peach orchards, perfectly free from blight or insect enemies, and in the proper season loaded down with luscious fruit of which the Mokis are extravagantly fond. A few cottonwoods among the fields, the peach trees, and the cedars along the mesa sides, are all the trees to be seen. These cedar forests are to the Moki towns what a vein of coal is to a civilized town—the fuel supply always getting farther away and harder to reach, because the annual growth of a desert cedar is almost imperceptible. Though veins of coal peep out in many places near the pueblos, the Mokis do not use it, although they seem to have known what coal is long before our wise men settled the question; the native name for it is "rock wood," koowa, a word which resembles our word coal. The score or so of fruits, grains and vegetables which the Mokis plant would, in favorable seasons, cause peace and plenty to reign in Tusayan, but Moki history has some sad tales of famine. When the crops fail, the "good people" of necessity fall back on the crops of nature's own sowing in the desert. Old people still gather a plant for greens, which they say has before now preserved the tribe from starvation. Dried bunches of this plant may often be seen ornamenting the rafters of their dwellings, amidst a medley of other curious things. The fare of the pueblo is eked out in ordinary times with edible roots,

SPINNER AND WEAVER.

seeds, berries, and leaves gathered from far and near. The Mokis are practical botanists. No plant has escaped their piercing eyes; they have given them names and found out their good and bad qualities; pressed them into service for food, medicine, religion, basket making and a hundred other uses, from an antidote for snake bites to a hair brush. They are also perforce vegetarians. Oñate, the Conqueror, said slightingly of Zuñi that there were as many rabbits as people around it. Such a condition of things in Tusayan would fill the Moki with joy, for he has the same fondness for rabbit as the negro has for "'possum with coon gravy." Snakes seem to be more plentiful than rabbits, although it takes ardent hunting to catch enough reptiles for the Snake dance. Rats, mice, prairie dogs and an occasional deceased burro or goat vary the menu of the pueblos. The Mokis never eat their dogs, though to do so would be at least putting them to some use.

DRESS WEAVING.Maude, photo.

that Arizonian oasis of flowers and plenty the ancestors of the Moki often must have sighed, but desert and a crust were preferable to the bloodthirsty Apache. This is the history of many an enforced migration.

Now, pursuing the order in which the traveler becomes familiar with the surroundings of the Moki, from the distant approach, when the mesas swim in the mirage with the dim outlines of the cell towns on their crests, to when he encamps by the corn fields and springs at their base, we will next toil up the trail to visit. Far out in the plain the watchful Moki from his high vantage has seen the approach of visitors, and the news flies fast. There will surely be some of the inhabitants to greet the traveler when he arrives, to wonder at his outfit, ask for piba and matchi (tobacco and matches), run errands and be on the lookout for windfalls of food. If the traveler wishes a washerman, a boy to graze the horses or carry water and wood, or if he wishes to rent a house, he will soon find willing hands and plenty of advisers. Shiba (silver) makes things run smoothly here as in civilization. Starting at the altitude of a mile and one-fourth, the climbing of a mesa

DYER.Voth, photo. is somewhat of a task to the unaccustomed. When the fierce sun is high, the climb may have frequent periods of pause, and the natives who run up and down the mesa as though it were a short flight of stairs are objects of envy. But when the ascent is made and one sits in the shade and hospitality of a Moki interior, the exertion is repaid. It is a new and memorable experience.

The nineteenth century civilization, with its tall buildings and bustling crowds, fades away and we are in the ancient past of the southwest wonderland.

The Mokis are almost invariably pleased to have white visitors enter their houses. Most of them invite you in, all smiles and hospitality. In most cases, though, where there is any doubt it is better to say, "een quaqui êsi?" (am I welcome?) which brings a hearty response. The houses have thick walls of flat stone, laid up in mud, plastered inside and out, and are pleasantly cool in the summer. The hard, smooth, plastered floor is the general sitting place, with the interposition of a blanket or sheepskin. The low bench, or ledge, which often runs around the room, is also used as a seat. Perhaps the ceiling will appear strange. The large cottonwood beams with smaller cross-poles backed with brush; above that, grass and a top layer of mud form a very picturesque ceiling and effective roof. From the center of the ceiling hangs a feather tied to a cotton string. This is the soul of the house and the sign of its dedication; no house is without one. Around the walls and from the beams hang all sorts of quaint belongings—painted wooden dolls, bows and arrows, strings of dried herbs and mysterious bundles, likely of trappings for the dances—enough to stock a museum. In well-to-do families the blanket pole, extending across the room, is loaded with their riches in the shape of harness, sashes, blankets and various other valuables. In one corner is a fireplace with hood; sunk in the floor are the corn mills; near by is a large water jar with dipper, and sundry pieces of pottery are scattered about. Usually the

MAKING BREAD (PIKI).

an old curiosity shop of articles—eagle traps, gourds, hoes, planting sticks, sheep bones, and many other articles that keep one guessing. On the top of a house in Moki-land once was seen a curious structure, having slanting sides formed of bits of boards. On closer examination it was found to be a plow, which the good people at Washington had sent the Mokis, now doing service as a chicken coop. Outside the door by the street is the pigame oven, in which green corn pudding is baked, food dear to the Moki heart and acceptable to any white visitor who does not know that the women chew the yeast to ferment the batter. This oven is a pit in the ground two or three feet deep. Before baking, a fire is made in it, and after the walls of the oven are heated the ashes are raked out and the pudding, called pigame, is put in and the top covered with a stone on which the fire is kept burning. The pudding is put in the oven at

SICHOMOVI FOOT TRAIL.

nightfall usually, and by morning it is well baked and ready to be wrapped in corn husks for consumption.

A stroll about a Moki town will convince the explorer that there are streets full of "surprises," as we call unexpected nooks and corners in our own houses. Just what the building regulations are no one has yet divulged, but the lay of the ground has much to do with the arrangement. Wolpi is crowded upon the point of a narrow mesa, and some of the houses are perched on the edge of the precipice, their foundation walls going down many feet, the building of which is a piece of adventurous engineering. Many of the towns have passages under the houses leading from one street to another. The stone surface of the street is deeply worn by the bare or moccasined feet of many generations. The trail over the dizzy narrows between Wolpi and Sichomovi is worn like a wagon track in places from four to six inches deep. The end of a ladder sticking up through a hatchway in a low mound slightly above the level of the street marks the way down into an underground

A MESA CLIFFSIDE. room, where strange ceremonies are held. This is a kiva, and if we are hardy enough to brave the usual warning to the uninitiated, we may peep down without fear of swelling up and bursting. Perhaps, if there is no ceremony going on, a weaver may be making a blanket on his simple loom; likely it is deserted, dusky and quiet with no suggestion of writhing serpents or naked votaries and weird chanting. All streets lead to the plaza, the center of interest, set apart for the many dances; some solemn and awe-inspiring, some grotesque and amusing; all dramatic in action and marvelous in color. In the center of the plaza is a stone box. This is a shrine, the focus at which all ceremonies center, and beneath it is the opening into the underworld of

POTTERS.

departed ancestors. Around most plazas in Tusayan the houses are built solidly; at Wolpi the dances take place on a narrow shelf above the dizzy sandstone cliffs; at Oraibi one side of the plaza where the Snake dance is enacted is open and the distant San Francisco mountains stand plainly on the horizon.

Outside the town there is also something to see. The general ash pile with its stray burro engaged in a hopeless task of finding something to eat is passed by, and one looks down over the brow of the mesa at the corrals among the rocks on a narrow ledge crowded with bleating sheep and goats. The trails wind down the mesa, across the fields, and are lost in the country lying spread out below like a map. Under the rocks a woman is digging out clay for pottery, other women are toiling up with jars of water from the

Maude, photo.

A MOKI FAMILY.

AN ORAIBI GIRL.

of visitors with horses camping about a pueblo will give rise to fears of a water famine. Placed on the borders of every spring, down close to the water, may be seen short painted sticks with feather plumes—prayer offerings to the gods for a continued supply of the precious fluid, the scarcity of which from clouds or springs has had to do with the origin of many ceremonies in the Southwest. The lack of water even fills in a large part of the conversation of white visitors in this dry country, taking the place of the weather, which is unlikely to change.

Let us follow up the trail again after the toiling water carriers, returning from the general meeting and gossiping place, the spring. Let no one think that there has been a lack of company in the course of these wanderings. There are the children first, last and all the time, all pervading, timid, but made bold by the prospect of sweets. It is amusing to see a little tot come hesitatingly as near as he dares to a white visitor, and say, "Hel-lo ken-te" (candy). Unclad before three or four years of age, the little ones look like animated bronzes—"fried cupids," one amused onlooker has termed them. The older girls have general charm of the young ones, and carry them about pick-a-back; sometimes it is difficult to tell whether the carrier or

A MISHONGINOVI GIRL.

the carried is the larger. The children are good, and seem never to need correction, and anyone can see with half an eye that the Mokis love their little ones. They never are so flattered as when attention is paid to the children. Do this with an admiring look, accompanied by the word "Lo′-lomai" (good, excellent, pretty), and the parental heart is won. When the rains fill the rock basins on the mesa, these youngsters have a famous time bathing, squirming like tadpoles in the pools, splashing and chasing each other. The Moki childlife must be a uniformly happy one, except in the season of green things, when they are allowed to eat without limit. The statistics of highest mortality must coincide with the time of watermelons, which are never too unripe to eat. Dogs, chickens and burros also add to the picturesqueness of a Moki village. The burros have the run of the town, and furnish amusement for the children. When providence or luck has prevented a burro from stealing corn, his ears have a normal, if not graceful length. Few there are, though, that have not paid penalty by the loss of one or both of these appendages. Chickens and dogs are a sorry lot. The latter lie in the corners and shady places, and only become animate and vocal at night, with true coyote instinct.

A MISHONGINOVI WOMAN.

SNAKE KIVA, ORAIBI.

Copyright, 1896, by G. Wharton James.

Used by permission.

ANTELOPE ALTAR IN KIVA.

THIEF BURRO.

man's flour, purchasable from the trader. Besides their customary work, some of the women have other occupations. At the East Mesa she may be a potter, at the Middle Mesa or Oraibi a basket maker, but never a weaver, for that, strangely enough, is man's work. In the quiet of her house the basket maker is busy, for are not many Pahanas coming to the Snake dance? Sugar and baking powder for the feast may depend on the sales of baskets. Around her on the floor are gay colored splints of yucca leaf, dyed with the evanescent aniline colors introduced by the traders. Some of the strips are being moistened in a bed of damp sand, from which they are taken to be sewn through and over, covering the coil of grass with geometric designs. The needle is really an awl; now of iron, formerly of bone. At Oraibi, where one of the three Snake dances held in Tusayan in the even years occurs, painted baskets of wicker are made. They are very decorative. The potter also plies her craft for the advent of the white man. The clay has been gathered, prepared, and made into vessels of forms tempting to the visitor, painted and burned at the foot of the mesa so that the villainous smoke will not choke everyone. Her wares are quaint and not half bad. Nampeo, at Hano, is the best potter in all Moki-land.

Of course little figures have to be carved from cottonwood, painted and garnished to resemble the numerous divinities of the Mokis who take part in the ceremonies. Men and women make them for their children, who thus get kindergarten instruction on the appearance of the inhabitants of the spiritual world. These "dolls" can often be bought; they are among the most curious souvenirs of the Moki. The weaver, too, spends his odd times in weaving the far-famed blankets of wool, dyed blue with sunflower seeds. He knows well the way to weave pretty diaper patterns which remind one of French worsted designs. The blankets are serviceable to the last degree and in the loose garment of the women will, perhaps, endure a whole generation. Belts of bright colored yarns, embroidered kilts of cotton and embroidered woolen sashes are chef-d'œuvres of the weaver.

The light side of life is uppermost in Moki-land. The disposition of the Moki is to make work a sport, necessity a pleasure and to have a laugh or joke ready in an instant. This is the home of song makers; the singing of the men at work, of the mother to her babe, of the corn grinders, of the priests in assembly chamber or in the kiva-vault, constantly ripples forth. There is no need for songs of the day; love songs, lullabys, war songs, hunting songs, songs secular and religious give variety in plenty. The dark side exists, to be sure, but the Mokis are so like children that a smile lurks just behind a sorrow. The seriousness and gravity with which the ceremonials are conducted is very impressive, and no one who has seen the Snake dance will fail to note that the Moki can be grave at times. Telling stories is one of the amusements of winter around the fireside. Until the ground is frozen it is dangerous to relate the deeds of the ancients: then they have gone away and will not overhear to the harm of the storyteller. Rabbit hunting is another favorite amusement, and parties of young men often do more hard work in one day thus than in a month otherwise with few results to show of "long ears" slain by the curved boomerang. In the proper season berrying parties go out for a day's picnic; the Mokis enjoy traveling, and a journey of fifteen or twenty miles to a berry patch and back is not thought anything out of common. When the green corn comes then the Moki lives bountifully. Tall columns of white steam arising in the cornfields at early morning invite to a feast of roast corn taken from the newly opened pit-oven. Then there is feasting while the ears are hot and jollity reigns. One thing will strike the visitor as curious: the Mokis do not gamble or drink fire-water, even when they have an opportunity. They do like tobacco, though, and the visitor who smokes will do well to lay in an extra supply, for after the first greeting, "piti," the next query will be "piba" (tobacco), followed by "matchi" (matches), and a friendly smoke council is held then and there.

The Mokis are the best entertained people in the world. A round of ceremonies, each terminating in the pageants called "dances," keeps going pretty continuously the whole year. The theaters and other shows in the closely built pueblos of the white man fall far short of entertaining all the people, as do the Moki shows. Then the Moki spectacles are free. The scheme of having a gatekeeper on the trails to demand an entrance fee, while it has great possibilities, has never entered the Moki mind. This, too, for a good reason. These ceremonies are religious and make up the complicated worship of the people of Tusayan. Even a visitor bent on sightseeing alone will be impressed with the seriousness of the Indian dancers and the evidence of deep feeling—perhaps it should be called devotion—in the onlookers. Not only in the somber Snake dance, but in every other ceremony of Tusayan the actors are inspired by one purpose and that is to persuade the gods to give rain and abundant crops. So the birds that fly, the reptiles that creep, are made messengers to the great nature gods with petitions, and the different ancestors and people in the underworld are notified that the ceremony is going on that they too may give their aid. The amount of detail connected with the observance of one of the ceremonies is almost beyond belief, and being carried on in the dark kivas has rarely been witnessed by others than the initiated priests. Thus the many observances which come around from time to time in two years are quite a tax on the memory of the adepts.

A TEWA GIRL.

The ceremonial year of the Moki is divided equally by two great events, the departure of the kachinas in August and their arrival in December. The kachinas are the spirits of the ancestors whose special pleasure it is to watch over Tusayan. When the crops are assured they depart for Nuvatikiobi, "the place of the high snows," or San Francisco Mountain. After their departure come the Snake and Flute dances, among others, and all the dances up to the return of the kachinas are called "nine days' ceremonies," while the joyous kachina dances are known as the "masked dances."

All who become acquainted with the Mokis learn to respect and like them. Fortunate is the person who, before it is too late, sees under so favorable aspect their charming life in the old new world.

Walter Hough.

THE SNAKE LEGEND.

It is only the ninth day's ceremony, the dance with the snakes, which is publicly performed.

MOKI CEREMONIES.

It will be noted that the Snake dances occur during the month of August, the date being between the 15th and 26th, and announced a few days prior to the beginning of the nine days' ceremonies, of which the dance is the public culmination. In the even years (1900, 1902, 1904, etc.) they occur at Oraibi, Shipaulovi and Sichomovi; in the odd years (1901, 1903, 1905, etc.), at Wolpi and Mishonginovi. The Flute dances, a picturesquely impressive but less exciting ceremony, occur at the above-named pueblos in years alternating with the Snake dance. For example, 1900 being the year of the Snake dance at Oraibi, the Flute dance at that pueblo will occur in 1901; and 1899 having been the year of the Snake dance at Wolpi, a Flute dance will occur there in 1900.

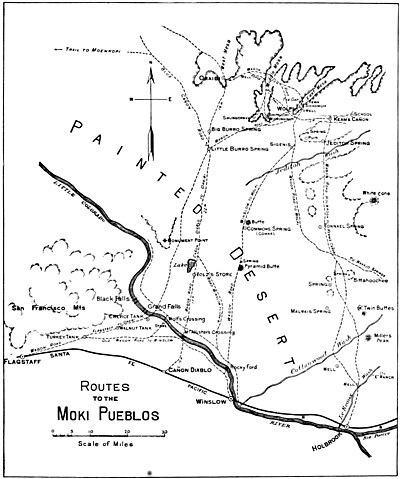

ROUTES TO THE MOKI PUEBLOS.

Far from being difficult of access, the Province of Tusayan is easily reached either by saddle horse or wheel conveyance from several towns on the Santa Fe Pacific Railroad, a division of the transcontinental line of the Santa Fe route. The trip can be made most conveniently by travelers to or from California as a side excursion en route, but the experience will amply repay a special journey across the continent. Some fatigue and lack of comforts incident to roughing it are well-nigh inseparable from such an excursion, involving as it does the traversing of from seventy to over one hundred miles of the Great American Desert, depending upon the point selected for departure from the railroad. But these very features are accounted no small part of the attractions of the trip, as lovers of outdoor life amid scenes of novel and extraordinary interest need not be told. Indeed, if the pueblos as an objective point did not exist, a voyage into that country of extinct volcanoes and strangely sculptured and tinted rocks and mesas would be well worth the making. While the round trip from the railroad may be made in four or five days, or less if desired, it can be pleasurably prolonged indefinitely. Aside from the powerful charm exerted by this region upon all visitors, there is an invigorating tonic quality in the pure air of Arizona that is better than medicine for the overworked in the exhausting activities of city business life. Many a professional man (and woman), wearied in brain and enfeebled in body, having been solicited to make this or a similar outdoor excursion in Arizona, has complied with misgiving and returned almost miraculously restored to health and vigor. Testimony to this fact can be furnished by reference to many well-known individuals, who, were they entirely free to indulge their preferences, would every summer forego the seaside and the fashionable watering-place and return to Arizona to mount a sturdy bronco, and forget for a time the cares and conventionalities of civilized life in a simple, wholesome and joyous existence in the sunlit air of the desert.

At the stations named all needful transportation facilities are provided, whose proprietors are accustomed to convey passengers every summer to the Snake dances. A visit to the Moki pueblos may, however, be made at any season, except in midwinter, and will at any time prove richly interesting. Arrangements should be made in advance by correspondence, which may be addressed to either the local agent of the Santa Fe Route, W. J. Black, General Passenger Agent, Topeka; C. A. Higgins, Assistant General Passenger Agent, Chicago; W. S. Keenan, General Passenger Agent, Galveston; Jno. J. Byrne, General Passenger Agent, Los Angeles; or John L. Truslow, General Agent, San Francisco.

[Note.—The distances given are approximate, as in some cases, particularly between the different pueblos, they depend upon whether the wagon or the horse trail is followed, the latter being shorter. The transportation charges also depend somewhat upon the size of the party. One or two persons traveling light by way of the shortest route could reach Oraibi in one day if desired. Larger or more leisurely parties would require two days, or longer by the less direct routes.]

Cañon Diablo Route.

| To McAllister's Crossing | 15 | miles |

| Volz's Store, "The Fields" | 17 | miles“ |

| Little Burro Spring | 22 | miles“ |

| Big Burro Spring | 3 | miles“ |

| Oraibi | 16 | miles“ |

| 73 | miles“ | |

| Middle Mesa | 20 | miles“ |

| 93 | miles“ | |

| Wolpi | 10 | miles“ |

| 103 | miles“ |

Note.―From "The Fields" there is a horse trail, northeasterly course, to Middle Mesa, 43 miles, and to Wolpi, 53 miles.

Charges.—$20 round trip, for conveyance by wagon; meals $1 each, and lodging $1 per night.

Winslow Route.

1.

| To Rocky Ford Crossing | 9 | miles | ||

| Junction with Cañon Diablo road north of Volz's Store | 30 | miles“ | ||

| Little Burro | 20 | miles“ | ||

| 59 | miles | |||

| Oraibi | 20 | miles“ | ||

| 79 | miles“ | |||

| Wolpi | 22 | miles“ | ||

| 81 | miles“ | |||

| Wolpi to Middle Mesa | 10 | miles“ | ||

| Middle Mesa to Oraibi | 20 | miles“ | ||

| 111 | miles“ | |||

| 2. | ||||

| To Rocky Ford Crossing | 9 | miles | ||

| Pyramid Butte | 26 | miles“ | ||

| Commoh's Spring | 10 | miles“ | ||

| Touchez-de-nez (Sigenis) | 25 | miles“ | ||

| Wolpi | 5 | miles“ | ||

| 75 | miles“ | |||

| Middle Mesa | 10 | miles“ | ||

| Oraibi | 20 | miles“ | ||

| 105 | miles“ | |||

Charges.—Named on application. Team and driver for four should cost not to exceed $5 per day, passengers furnishing their own bedding and provisions. Winslow is provided with hotel accommodations and outfitting stores.

Holbrook Route.

| To La Reaux Wash | 11 | miles |

| Well near Cottonwood Wash | 6 | miles“ |

| Cottonwood Wash crossing | 3 | miles“ |

| Malpais Spring | 13 | miles“ |

| Bittahoochee | 7 | miles“ |

| Tonnael Malpais Spring | 12 | miles“ |

| Jeditoh Valley Spring | 22 | miles“ |

| Keam's Cañon | 6 | miles“ |

| Wolpi | 10 | miles“ |

| 90 | miles“ | |

| Middle Mesa | 10 | miles“ |

| Oraibi | 20 | miles“ |

| 120 | miles“ |

Charges.—$15 round trip, for conveyance by wagon, passengers providing their own camp outfit and provisions. Holbrook has good livery and hotel accommodations, and stores.

Flagstaff Route.

| To Turkey Tanks | 19 | miles |

| Grand Falls Crossing | 22 | miles“ |

| Little Burro | 45 | miles“ |

| Oraibi | 18 | miles“ |

| 104 | miles“ | |

| Middle Mesa | 20 | miles“ |

| Wolpi | 10 | miles“ |

| 134 | miles“ |

Charges.—For wagon conveyance, $25 round trip. Board $3 per day, and lodging $1 per night. Or passengers may provide their own outfit and provisions and arrange with liverymen for transportation only. Hotel accommodations, livery and stores at Flagstaff are excellent.

It is also practicable to make the trip from Gallup. This route is not shown on map herein, but is reported to be as below:

| To Rock Spring Store | 9 | miles |

| Hay Stack Store | 12 | miles“ |

| (Fort Defiance, 9 miles north.) | ||

| Cienega | 5 | miles“ |

| Bear Tank (water 1½ miles north) | 20 | miles“ |

| Cotton & Hubbell's Store (Gañada) | 11 | miles“ |

| Eagle Crag (water 1½ miles north) | 23 | miles“ |

| Steamboat Cañon (water 3 miles north) | 8 | miles“ |

| Keam's Cañon School | 18 | miles“ |

| Keam's Cañon Store | 2 | miles“ |

| Wolpi | 10 | miles“ |

| 118 | miles“ | |

| Middle Mesa | 10 | miles“ |

| Oraibi | 20 | miles“ |

| 148 | miles“ |

The Province of Tusayan, site of the Moki Pueblos, is situated north of the railroad west of Albuquerque,

and is thus indicated: □