The Music of Bohemia/Part II

PART II

Why Bohemian music or Czech music or Slovak music or Czechoslovak music? Does there exist any nationality in music?

Every nation, with its mother-tongue, its peculiar customs, its distinct mode of life, varies more or less in form of culture from all other nations. The differences of geographical positions, racial inclinations, and inborn temper influence all departments of life—even Art. "No man can quite emancipate himself from his age and country or produce a model in which the education, the religion, the politics, usages, and arts of his times shall have no share. He cannot wipe out of his work every trace of his thoughts amidst which it grew. Above his will and out of his sight he is necessitated by the air he breathes and the idea on which he and his contemporaries live and toil, to share the manner of his times, without knowing what that manner is." (Emerson.)

And as a man cannot escape from his own people and his own time, so he cannot escape from all peoples and all times. The greater the artist, the more he expresses the life of all mankind, the more he becomes the universal artist; and strangely enough, the more he becomes the pride of his nation. The world speaks of his work as the representative art of his nation, and discovers in it something that we call "nationality." In this sense Smetana is the founder of a style which is called "Czech national music."

Bedřich Smetana (1824–1884) was endowed by nature with a rare gift of musical initiative. While a wee child of five he was already playing the violin and composing; as a poor student he returned one evening from a concert of chamber music and wrote down a string quartet he had heard, because he could not buy a copy of it. Like Beethoven, he lost his hearing in the time of his most intensive period of creation. When deaf and persecuted by the malignity of his enemies, when fate knocked on his door with its iron hand and robbed him of his wife and child, his genius created the greatest works. The high spiritual plane of his life as it touched the personal and the accidental is revealed in the charming string quartet "From my Life."[1]

"My quartet," says Smetana, "is not merely formal playing with the tones and motifs, to show off the composer's skill; but it is the real picture of my life. The tone sounding for a long time in the Finale is that whistling sound of very high pitch, which had preceded my deafness. This little tone-picturing I dared to insert in this composition because it was so fateful for me."

Smetana always found in the small ensemble of chamber music the proper interpreter for expression of his most intimate feelings. Thus the Trio, op. 15,[2] was written to the memory of his little daughter, whose death brought to Smetana a great sorrow.

Smetana never accommodated his artistic principles to the taste of the public. He was too serious an artist to make a work pleasing to the masses. His eight operas—except The Bartered Bride—had to fight against a wall of misunderstanding; and were victorious, only after many years of dispute, because of their originality and vitality. A real genius, Smetana was much ahead of his time.

The Bartered Bride[3] (1866), Two Widows (1874), The Kiss (1876), The Secret (1878), and The Devil's Wall (1882) represent the highest style of the modern comic operas. Each of these works introduces a charming overture of a pure musical beauty, classical in form. Dalibor (1868), a historical-romantic opera, became a favorite even outside its native land. The story is based upon a Czech folk-legend of the fifteenth century, which tells about a knight, Dalibor, who was a prisoner at the castle in Prague. He begged his jailor for a violin to lighten the heavy hours of his captivity. After a time, it is said, he played with such marvelous skill that the people came from far and wide to stand outside the prison walls and listen to the charming music. Likewise the libretto to the festival opera Libussa (1881), is drawn from the Czech history. This work marks the climax of Smetana's genius, and a knowledge of it is indispensable to the student of Czech musical art. The overture to this opera is a masterpiece of form and festival mode.

It begins with a trumpet call, developed in a

tremendous gradation. Surely this work ought to be heard at least in a concert hall.

Considering the technical side, Smetana's works exhibit a great skill in the most problematic combinations of the polyphonic style flowing so naturally, that the hearer does not notice the difficulties solved with such exquisite grace and lightness. The melodies are fresh, original,[4] and impressive; and enriched with Smetanian harmonic peculiarities. Speaking of the harmony, I want to disclose this fact, that in his piano sketch, "A Scene from Macbeth," composed in the year 1859, there was introduced for the first time in the history of musical literature, the whole tone scale:

![\new PianoStaff << \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\new Staff {

\key e \major

\relative c' {

<< {

\autoBeamOff

<gis gis'>8[ <b' b'>8^^] <a a'>8^^[ <fisis fisis'>8^^] |

\tuplet 3/2 { <eis eis'>8^>[ <dis dis'>^> <cis cis'>^>] }

<b b'>8.^>[ <a a'>16^>] | <a a'>2

} \\ {

r16 <cis e>16 s4. | s2 | r16\( <bis dis fis>16\)[ <bis dis fis>16]

} >>

} }

\new Staff {

\clef bass \key e \major \time 2/4

\relative c' { gis,,8_> r8^\f <gis'' e'>8^^ r8 | r4 r8. gis,,16_. | gis8 r8 s4} }

>>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/j/f/jfll6hq9d8doyssn357wz8w4s7uzkve/jfll6hq9.png)

As a composer for the piano Smetana left a considerable number of works, especially Polkas, which he idealized in a very poetic form. His Polka No. 1, op. 7, was one of Liszt's favorites; the subject of this dance will not be thought devoid of interest in this place:

Two cycles of piano compositions, of which the first bears the title Rêves, and the other The Bohemian Dances, especially deserve the attention of the pianist. In this later work the Czech folk-melodies are preserved in very artistic and pianistic style. Smetana's best known composition, which is often played at concerts, is his étude By the Seashore, op. 17, a difficult but very effective piece of music snatching the spell of the Northern Sea.[5]

In the last period of his creation Smetana expressed his love and admiration for his country and its history in poems in a cycle called My Country, consisting of six charming symphonic poems: Vyšehrad, the old castle, the seat of the first Bohemian ruler; Vltava, the river of Bohemia; Šárka, the Bohemian Amazon; From Bohemian Meadows and Woodlands, an idyll; Tábor and Blaník, which picture in tones the glorious past epoch of the Reformation. With this work the composer reached his goal. No greater tribute to his success is needed than Liszt's exclamation upon hearing of Smetana's death—"He was a genius!"

Anton Dvořák (1841–1904), the best known Czech composer, was a son of a village butcher. From his early childhood his only passion was music. In spite of many struggles and much suffering, he did not cease to study and work. Music was his consolation, his life. In just praise it may be said that the high position of this composer in the musical world is due chiefly to his unparalleled perseverance under his own criticism. To take a full orchestra score of a completed opera and destroy it and then rewrite it, was characteristic of Dvořák's method of attaining perfection. This self-teaching explains his temporary experimenting and uncertainty in form.

The number of Dvořák's compositions is vast, covering almost all forms of music. His fame began with Slavic Dances, brilliantly instrumented, which appealed to the larger public. Of his five symphonies the last one, From the New World, was composed while Dvořák was teacher of composition at the National Conservatory of Music in New York, in 1892. To this American period belongs the popular String quartet, op. 96, and his most beautiful as well as his last vocal opus, the cycle of The Biblical Songs, op. 99.

Whoever wishes to have a clear idea of Dvořák's genius must study and hear the wonderful symphonic poems from the last period of the composer's life. Here Dvořák, master of classical and absolute music, pays his tribute to the modern form of romantic program music with great success. As a composer of piano music, Dvořák could not subdue his eminent orchestral genius to clavier technique; his piano compositions call for instrumentation. The seventh number from opus 101 has become an extraordinary favorite in America; it is the celebrated Humoreske.

Of his seven operas the most beautiful is Russalka, which exhibits the best qualities of the author's creative ability. It may be said, however, that all Dvořák's operas are handicapped by a lack of conciseness. They cannot be compared favorably with Smetana's works in dramatic feeling. The interesting remark of Liszt, that "what Smetana deserved—Dvořák has reaped," should be modified to this extent, that these Czech masters never considered themselves rivals. Each fulfilled his task in his own way, and each appreciated the work of the other.

Zdenko Fibich (1850–1900) was the creator of the modern melodramas—recitations with music. The first Czech composer who wrote this unusual form was Georg Benda (1722—1795). His melodramatic compositions, Medea, Ariadna on the Naxos, appeared only two years after Rousseau's melodramatic experiments. Benda did not know anything about Rousseau's work and made his melodramas of his own initiative. His technique was essentially different from that used later by Beethoven in Egmont, by Schumann in Manfred, and by Fibich in his works. Benda never let his music be performed simultaneously with the recitations, but as an interlude between the short sections of the poetry.

One hundred years after Benda, Fibich revived melodrama in Bohemia, greatly changing and enriching its technique. Thus his trilogy, Hippodamia, performed in three evenings, is the first example in the history of music where the modern orchestra supports continuously the recitations of the actors. Fibich prepared himself for the great task of writing scenic melodrama by composing many concert melodramas, of which The Waterman became a favorite in Bohemia. These are very fine specimens of the form so often anathematized by aesthetes.

Fibich wrote also six operas in which he proved himself a master of dramatic style. It is a pity that these works are not better known. One of his operas, The Tempest, takes its subject from Shakespeare's play.

Modern Czech music is represented by the works of Vítězslav Novák (1870), a pupil of Dvořák. He is the greatest unrivaled talent of present Czech musical art. It is necessary to hear only his ocean fantasy, The Storm, op. 42, for soli, chorus, and orchestra, to get an idea of his elementary power of creation.

The principal theme from The Storm:

The magnificent art of interpretation of the Prague and Moravian Teachers inspired Novák to compose male choruses containing very often great difficulties for intonation; as an instance, in the

CHRISTMAS LULLABY

OP. 37, V

A special analysis would be necessary to discover Novák's melodic and harmonic richness in chamber music, piano compositions, and especially in songs. His Pan, op. 43, a poem in tones for piano solo, is one of the most marvelous works of the modern piano literature. It consists of five parts: Prologue, Mountains, Ocean, Woods, Woman.

Simultaneously with Novák came another Czech modernist from Dvořák's class in composition, Josef Suk (1874), the second violinist in the famous Bohemian String Quartet. He is a composer of absolute subjectivity with inclination to mysticism; a real poet, in both the most complicate symphonic forms and in short piano sketches. He wrote the first composition made under the suggestion of the great war in Bohemia, his Meditation, op. 35, for string orchestra, in which is heard the prayer from the old St. Wenceslas' Chorale: "Do not let thy nation perish!" with a new solemnity of accent.

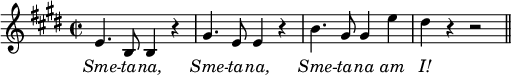

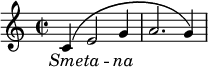

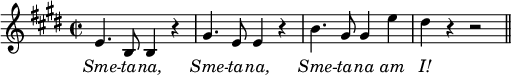

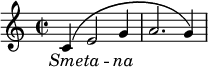

- ↑ When Liszt heard this composition in Weimar he remarked: "There is nothing to be said. It is very, very beautiful. We really enjoyed your wonderful quartet." In this connection it may be interesting to note the following anecdote about Smetana and Liszt, who were great friends. On one occasion Liszt introduced Smetana to his German friends, who naturally pronounced his name with a wrong accent, as the English would do. Liszt corrected them with a clever musical joke, using two motifs from Beethoven's Leonore and Fidelio overtures; the first, pointing out the correct accent on the first syllable:

The other pointing out the wrong accent on the second syllable.

- ↑ Trio in G minor, op. 15, for piano, violin, and violoncello.

- ↑ Was performed for the first time in America in 1909 at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York, with great success.

- ↑ Smetana's inventive power was never exhausted; he was often compared to Mozart. By no means should his melodies be mentioned in relation with Czech folk-song; the statement about The Bartered Bride that "National melodies and national rhythms furnish the chief stock of the work," and that "the overture is a masterly setting of folk-song material in fugal style" (The Opera, vol. ix in The Art of Music), has to be corrected. There is no trace of Czech folk-song in the whole opera.

- ↑ It was composed in Sweden, in 1862, with original title Vid Stranden, Mine af Sverige, while Smetana was a musical director in Göteborg.