The Pinafore Picture Book/Chapter 4

T was night, and a beautiful crescent moon was shining over the placid blue waters of Portsmouth Harbour. All the hammocks had been taken from the receptacles on deck called hammock-nettings in which they were kept during the day, carried below, and hung up from hooks in the beams of the lower decks. The sailors who were not required on deck were supposed to be fast asleep in them, but I'm afraid they slept with one eye open, because it would soon be time for them to escape secretly from the ship in order to accompany Ralph Rackstraw and the beautiful Josephine to Portsmouth Town to be married. Josephine did not go to bed at all, but was busily occupied in packing up a few indispensable necessaries (not forgetting her paste-board nose) in a small handbag, and in writing an affectionate farewell letter to her kind Papa. Now I want it to be distinctly understood that Josephine was very much to be blamed for the step she was about to take. In the first place, a young lady should, under no circumstances, fall in love with a young man greatly beneath her in social rank, and in the second place, no young lady should ever take such an important step as getting married without her Papa's express approval. In this case, Josephine had distinctly promised her Papa that she would never, under any circumstances, let Ralph Rackstraw know even that she had fallen in love with him, whereas here she was, actually preparing to leave the ship with him secretly in order that they might be married! It is true that it is some excuse for her that she revealed her affection for Ralph as the only means of preventing him from killing himself, but, having done that, she should have gone to her Papa without a moment's delay, and explained to him the dreadful circumstances under which she had felt bound to disclose her secret. Captain Corcoran had shown himself to be a most affectionate and sympathetic father, and he would, no doubt, have made every allowance for the distressing situation in which she found herself. He might even have gone so far (and I think he would) as to have provided masters for Ralph who would have taught him to spell and dance, drink soup without gobbling, eat peas with a fork, play bridge, and, in short, make him fit to take his place creditably among ladies and gentlemen.

T was night, and a beautiful crescent moon was shining over the placid blue waters of Portsmouth Harbour. All the hammocks had been taken from the receptacles on deck called hammock-nettings in which they were kept during the day, carried below, and hung up from hooks in the beams of the lower decks. The sailors who were not required on deck were supposed to be fast asleep in them, but I'm afraid they slept with one eye open, because it would soon be time for them to escape secretly from the ship in order to accompany Ralph Rackstraw and the beautiful Josephine to Portsmouth Town to be married. Josephine did not go to bed at all, but was busily occupied in packing up a few indispensable necessaries (not forgetting her paste-board nose) in a small handbag, and in writing an affectionate farewell letter to her kind Papa. Now I want it to be distinctly understood that Josephine was very much to be blamed for the step she was about to take. In the first place, a young lady should, under no circumstances, fall in love with a young man greatly beneath her in social rank, and in the second place, no young lady should ever take such an important step as getting married without her Papa's express approval. In this case, Josephine had distinctly promised her Papa that she would never, under any circumstances, let Ralph Rackstraw know even that she had fallen in love with him, whereas here she was, actually preparing to leave the ship with him secretly in order that they might be married! It is true that it is some excuse for her that she revealed her affection for Ralph as the only means of preventing him from killing himself, but, having done that, she should have gone to her Papa without a moment's delay, and explained to him the dreadful circumstances under which she had felt bound to disclose her secret. Captain Corcoran had shown himself to be a most affectionate and sympathetic father, and he would, no doubt, have made every allowance for the distressing situation in which she found herself. He might even have gone so far (and I think he would) as to have provided masters for Ralph who would have taught him to spell and dance, drink soup without gobbling, eat peas with a fork, play bridge, and, in short, make him fit to take his place creditably among ladies and gentlemen.

Poor Captain Corcoran had also been greatly worried by the events of the day. He had been severely rebuked by Sir Joseph, in the presence of his crew, for not having said "if you please" when he gave them an order; he had been greatly upset by his daughter's determination to decline Sir Joseph's handsome offer (and also by her short and snappish replies to Sir Joseph's pretty speeches at dinner that evening) and, to crown everything, Sir Joseph had threatened to have him placed under arrest and tried by Court Martial because he did not rebuke Josephine for her rudeness to him at dinner. Of course, if the First Lord of the Admiralty had known anything whatever about the Navy, he would have been aware that no Court Martial would have punished Captain Corcoran for his daughter's rudeness; but he knew nothing at all about the Navy, having, as we know, been brought up in a solicitor's office.

So instead of going to bed at his usual hour HER SHORT AND SNAPPISH REPLIES TO SIR JOSEPH'S PRETTY SPEECHES AT DINNER

This was the pretty song that he sang:

'Fair moon, to thee I sing

Bright regent of the heavens,

Say, why is everything

Either at sixes or at sevens?

I have lived hitherto

Free from the breath of slander,

Beloved by all my crew—

A really popular commander.

But now my kindly crew rebel,

My daughter to a Tar is partial,

Sir Joseph storms, and, sad to tell,

He threatens a Court Martial!

Fair moon, to thee I sing,

Bright regent of the heavens,

Say, why is everything

Either at sixes or at sevens?

The moon not being in the position to give him the required information, withdrew behind her cloud, and was seen no more.

Captain Corcoran had no idea that anyone except the moon was listening to him, as he sang, but in point of fact, Little Buttercup, who was concealed by the mizen-mast, had heard his beautiful light-baritone voice, and her attention was arrested by the charm of the dainty melody.

Now I must tell you something about Little Buttercup, who had had a very adventurous career. At the time of my story, she was a buxom, well preserved person, about sixty-five years of age. She had known Captain Corcoran all his life, and when he was a handsome young lieutenant of twenty five I am sorry to say she fell hopelessly in love with him, although the old goose was at least twenty years older than he. Lieutenant Corcoran (as he was then) commanded a little gun-boat called the Hot Cross Bun, and I should explain that a gun-boat, in those days, was a very small vessel, rigged something like a miniature ship, and was armed with one, two, or three big guns. Lieutenant Corcoran was then in the very flower of manly beauty, and all the young ladies of Portsmouth were quite as much in love with him as Little Buttercup was. Of course, Lieutenant Corcoran scarcely noticed Little Buttercup—she used to wash for the ship, and he only saw her now and then, when she brought his linen aboard. At length the Hot Cross Bun was ordered to make ready to go to sea, and Little Buttercup, who couldn't bear the thought that she might never see him again, dressed herself in sailor's clothes, and presented herself on board, as a (not very) young man who wanted to go to sea. Captain Corcoran, who, as a matter of course, did not recognize her in this disguise, accepted her as a member of his crew, and when the Hot Cross Bun sailed Little Buttercup sailed with it. She was extremely clumsy as a sailor, but the kind-hearted Lieutenant, who couldn't bear to hurt anybody's feelings, overlooked her awkwardness in consideration of the eager alacrity with which she endeavoured, however unsuccessfully, to obey all his commands. Indeed the crew, generally, were much more remarkable for gentle politeness and cheerful goodwill than for mere pulling and hauling. They were, without exception, most amiable and well-behaved young persons, with beautiful complexions, very dainty white hands, small delicate waists, and a great quantity of carefully dressed back-hair. Lieutenant Corcoran was bound to admit that as sailor-men they were not everything that could be desired, (being all very sea-sick when it was not quite calm), but, in his opinion, they more than compensated for this drawback by their singularly polite and refined demeanour when they were quite well.

One day (and it was a terrible day for Little Buttercup) he went on shore for a couple of hours, and returned with a beautiful young lady, whom he presented to his crew as his newly-wedded wife; upon which, to his intense discomfiture, all the crew gave a gurgle, and fell down in so many separate fainting fits, and he then discovered that, without a single exception, they were Portsmouth maidens who had dearly loved him and who had taken the very steps that Little Buttercup herself had taken, in order that they might not be separated from their adored Lieutenant! Of course they were all discharged at once (his bride insisted on that), and Little Buttercup did not see him again for twenty long years. By this time he had been promoted to be Captain of the Pinafore; his wife had died, and he was left a widower with one daughter, the beautiful Josephine, who is the heroine of my story.

From the moment that Little Buttercup learnt that Lieutenant Corcoran was a married man she determined, as a matter of course, to think of him no more, and, by a tremendous effort, she succeeded in banishing him altogether from her mind; but, now that he was a widower and again free to marry, all her old affection revived. By this time, as you know, she was a bum-boat woman, and in that capacity she enjoyed many opportunities of seeing and talking to Captain Corcoran, who hadn't the remotest idea that she had formerly been one of the lady-like crew of the Hot Cross Bun, and Little Buttercup never mentioned the circumstance, as, to tell the plain truth, she was not particularly proud of it.

As the Captain sang his song, Little Buttercup wondered what was the matter with him.

"How sweetly he carols forth his melody to the listening moon," said she to herself. "Of whom is he thinking? Of some high-born beauty? It may be! Who is poor Little Buttercup that she should expect his thoughts to dwell on one so lonely?"

"Ah, Little Buttercup," said Captain Corcoran, as he caught sight of her, "still on board? That is not quite right, little one—all ladies are requested to go on shore at dusk."

"True, dear Captain," she replied, "I tried to go, but the recollection of your pale and sad face seemed to chain me to the ship. I would fain see you smile before I leave."

"I will try," said he.

He endeavoured to smile, but it was little more than a creaky mechanical grin.

"Not good enough, Captain," replied Little Buttercup, "don't be faint-hearted; try again, because I want to go home."

Again he tried to smile, but without success.

"Ah, Little Buttercup," said he, "I fear it will be long before I recover my accustomed cheerfulness, for misfortunes crowd upon me, and all my old friends seem to have turned against me!"

"Do not say 'all,' dear Captain," exclaimed Little Buttercup. "That were unjust to one, at least!"

"True," said Captain Corcoran, "for you are staunch to me. Good old Buttercup!"

At this point poor Little Buttercup's resolution gave way. With a bitter cry she knelt at his feet, and sobbed loudly as she kissed his hand.

"Little Buttercup," said Captain Corcoran, "it would be affectation to pretend that I do not LITTLE BUTTERCUP AND THE CAPTAIN

Little Buttercup, who always knew more about people than anybody else, knew a good deal of Captain Corcoran's history, as will presently appear. He was not really Captain Corcoran, and she knew it. More than that, she knew who he really was, but it did not suit her to tell him just then. I believe that this mysterious Little Buttercup was able to prove, from the hidden depths of her miscellaneous information, that every human being alive was somebody else, and that no human being alive was what people really supposed him to be. Fortunately, she only revealed her knowledge bit by bit as it suited her, but it is terrible to think what an amount of confusion she might have created in highly respectable families if she had chosen to disclose all she knew at once.

Knowing who Captain Corcoran was, and how little reason he really had to plume himself on his superior position as a Captain in the Navy, Little Buttercup's naturally hasty temper began to simmer. The gipsy blood that ran in her veins gave her a curious power of prophesying backwards. I mean that she could foretell what you were, and remember what you will be, which is quite unlike the usual kind of fortune-telling that comes of crossing a gipsy's hand with a sixpence. She also possessed a remarkable power of expressing herself in rhyme without ever having to hunt for the last words of her lines, which gave a peculiar force and emphasis to her words, and convinced everybody that what she said was supernatural, and consequently true.

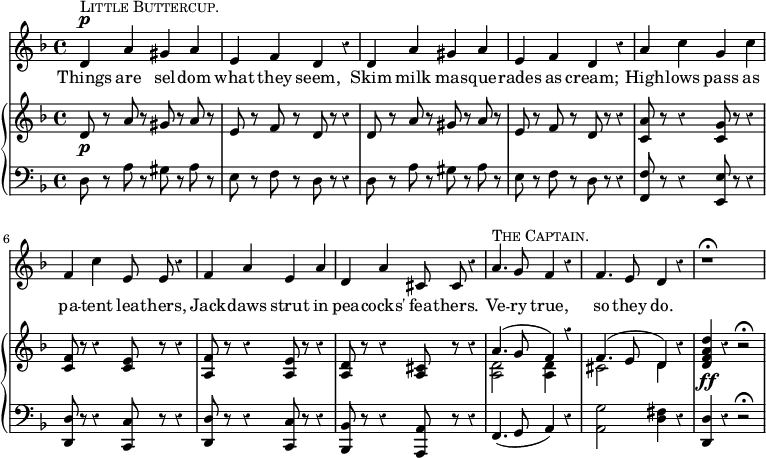

So, getting gradually more and more angry with Captain Corcoran for despising her, as she called it (though he was the last person in the world to despise anybody) she summoned her remarkable rhyming ability to her aid in the following utterances:

Things are seldom what they seem (said she)

Skim-milk masquerades as cream;

High-lows pass as patent leathers;

Jackdaws strut in peacocks' feathers.

Rhyming is rather infectious, so Captain Corcoran, catching the disease, replied (rather puzzled)

Very true,

So they do!

Black sheep dwell in every fold; (said she)

All that glitters is not gold;

Storks turn out to be but logs;

Bulls are but inflated frogs.

The captain thought he could do as well as this, but he considered that it was best to confine himself at present to quite easy rhymes, so he said:

So they be

Frequentlee.

Buttercup resumed:

Drops the wind and stops the mill;

Turbot is ambitious brill;

Gild the farthing if you will,

But it is a farthing still.

The Captain replied:

Yes, I know

That is so.

Then, beginning to feel his feet, as the saying is, he ventured into deeper water:

Though to catch your drift I'm striving,

It is shady—it is shady.

(He repeated "it is shady" to give him time to think of the next rhyme, though he pretended that the repetition was part of the structure of the verse.)

I don't see at what you're driving,

Mystic lady—mystic lady!

Having discovered that this sort of rhyming was much easier than it appeared at first sight to be, he determined to show her that other people were just as smart as she was, and (if you come to that) even a little bit smarter.

So he began:

Though I'm anything but clever,

I could talk like that for ever.

Once a cat was killed with care:

Only brave deserve the fair.

Very true,

So they do.

said Little Buttercup (mimicking his own way of replying to her). The Captain continued:

Wink is often good as nod;

Spoils the child who spares the rod;

Thirsty lambs run foxy dangers;

Dogs are found in many mangers.

Here he paused to consider what he should say next, and Little Buttercup (to give him time) said, just as before:

Frequentlee,

I agree.

By this time the Captain had thought of something more:

Paw of cat the chestnut snatches;

Worn-out garments show new patches;

Men are grown-up "catchy-catches."

Yes (said Little Buttercup) I know

That is so.

Then she sang, under her breath, so that nobody at all should hear her.

Though to catch my drift he's striving,

I'll dissemble—I'll dissemble—

When he sees at what I'm driving

Let him tremble—let him tremble!

and, muttering to herself in a fashion which might be described, musically, as a triumph of pianissimo, she disappeared mysteriously into the forward part of the ship.

Captain Corcoran—though very uneasy at her portentous utterances—was rather disposed to pat himself on the back for having tackled her on her own ground in the matter of stringing rhymes, and (as he thought) beaten her at it. But in this he was wrong, for if you compare her lines with his, you will see that whereas her lines dealt exclusively with people and things who were not so important as they thought themselves to be, his lines were merely chopped-up proverbs that had nothing to do with each other or with anything else. Still it wasn't bad for a first attempt, and although we must give her the prize, I think he deserves a "highly commended."

Now although Sir Joseph had gone to bed, he was so worried about Josephine that he couldn't get a wink of sleep. So as it was a beautiful warm night, and everybody (as he supposed) asleep, he thought he would go on deck in his pyjamas, and console himself with a cigar. Accordingly he went on deck, but finding that the Captain was in close conversation with a lady, he very properly retired to his cabin to put on the beautiful and expensive uniform of a Cabinet Minister which he had worn during the day, and which were the only clothes he had brought with him. He had completed his toilet and returned to the deck just as Captain Corcoran was endeavouring to pat himself on the back for his cleverness in stringing rhymes with Little Buttercup.

"What are you trying to do?" said Sir Joseph, as he noticed that the Captain had some difficulty in reaching the exact part of the back which he wished to pat. "Can I help you?"

"Thank you, Sir Joseph," replied the Captain, "I have a particular reason for wishing to pat self between the two shoulder blades, and—and it's not easy to get at."

"Allow me, Captain Corcoran," and he obligingly patted him on the very spot.

"Thank you, Sir Joseph, that is capital," said Captain Corcoran, much relieved, "but I am sorry to see your Lordship out of bed at this hour. I hope your crib is comfortable."

"Pretty well," said Sir Joseph, who made it a rule never quite to approve of anything that was done for him, " the fact is I am worried about your daughter. I am disappointed with her. To tell the plain truth, I don't think she'll do."

"I'm sorry to hear that, Sir Joseph," replied the Captain, "Josephine is, I am sure, sensible of your condescension."

"She naturally would be," said Sir Joseph, who was really too conceited for words.

"Perhaps your exalted rank dazzles her," remarked Captain Corcoran.

Here again we become conscious of that nasty irritating little blot on the good Captain's character. He attached so much importance to mere rank that I am afraid we must put him down as just a teeny-weeny-wee bit of a sn-b.

"WHAT ARE YOU TRYING TO DO?" SAID SIR JOSEPH

"Well, she is a modest girl, and, of course, her social position is far below that of a Cabinet Minister. Possibly she feels that she is not worthy of you."

Captain Corcoran knew better than that, but his natural kindness of heart would not allow him to tell Sir Joseph the plain truth—that Josephine looked upon him as a conceited donkey, because he was afraid that, being a touchy old gentleman, he might not like that.

"That is really a very sensible suggestion," said Sir Joseph.

"See," said the Captain, "here she comes. If you would kindly reason with her and assure her officially, that it is a standing rule at the Admiralty that love levels all ranks, her respect for an official utterance might induce her to look upon your offer in its proper light."

"It is not unlikely," said Sir Joseph, "and I am glad I am not wearing my pyjamas. Let us withdraw and watch our opportunity."

So they withdrew behind the mast, as Josephine stepped upon deck.

Poor Josephine was very uneasy and conscience-stricken at the unjustifiable step she was going to take that night. As the moment for her flight approached, she became more and more uncomfortable; and as her cabin was hot, and the night lovely, she thought she would wait more comfortably on deck until the fatal moment for her departure.

Naturally a good and honourable young lady, she felt that she was doing an unpardonable thing in leaving her good Papa secretly in order to marry a man of whom she knew that he disapproved. In common fairness, however, it should be explained that it was the first time she had ever left her father in order to be secretly married to anybody, and she resolved that, after this once, nothing on earth should ever induce her to do so again.

Josephine had a neat literary turn, and it was her practice to express, in poetical form, the various arguments for and against any important step that she contemplated taking. She had amassed quite a large amount of these effusions, which she was in the habit of singing, on appropriate occasions, to any airs that would fit them. So, finding herself quite alone (as she supposed) it occurred to her to sing, in subdued tones, a composition which had direct reference to her misguided affection for Ralph.

This was the song:

The hours creep on apace,

My guilty heart is quaking;

Oh, that I might retrace

The step that I am taking!

Its folly it were easy to be showing;

What am I giving up, and whither going?

On the one hand, papa's luxurious home,

Hung with ancestral armour and old brasses,

Carved oak, and tapestry from distant Rome,

Rare "blue and white," Venetian finger glasses,

Rich oriental rugs and sofa pillows,

And everything that isn't old, from Gillows'

And, on the other, a dark dingy room

In some back street, with stuffy children crying,

Where organs yell and clacking housewives fume,

And clothes are hanging out all day a-drying:

With one cracked looking-glass to see your face in,

And dinner served up in a pudding basin.

Oh, god of Love and god of Reason—say

Which of you twain shall my poor heart obey?

But the two potentates, so pathetically appealed to, declined to undertake the responsibility of advising her. I expect they both thought that she was quite old enough to judge for herself.

Poor Josephine was greatly distracted at the ugly prospect of love in a back street that she had conjured up for herself, and her resolution began to waver. The social difference between her and her chosen husband was so enormous, and the discomforts that she would be obliged to endure in the humble surroundings that awaited her presented themselves to her mind so vividly, that she had almost resolved that instead of eloping with Ralph, she would unpack her dressing-bag, put her hair up in Hinde's curlers, and go to bed like a good girl. I regret to think that, in contemplating this step, she was influenced solely by the fact that if she married Ralph she would have to surrender all the luxuries she was accustomed to, and that remorse for being about to break the heart of her affectionate and indulgent father did not appear to influence her in the least. I am very partial to Josephine, but I cannot regard her in the light of a thoroughly estimable young lady.

Sir Joseph endeavoured in vain to catch the words of Josephine's song, but she had been taught the Italian method of singing, which consists in "la-la-ing" all the vowels and allowing the consonants to take care of themselves, and consequently the words of her song were quite unintelligible to him—indeed they might have been Hebrew for anything he could tell. So when she had finished, he and Captain Corcoran approached her.

"Madam," said he, "it has been represented to

It is a rule at the Admiralty that when a person in authority has to make an announcement he is bound to use all the longest words he can find that will express his meaning.

"Oh, indeed," replied Josephine; "then your Lordship is of opinion that married happiness is not inconsistent with discrepancy in rank?"

This was artful on Josephine's part, for if Sir Joseph agreed, he would practically be admitting that there was no reason why Josephine should not condescend to marry a common sailor if she had a mind to do so.

"Madam," said Sir Joseph, loftily, "I am officially of that opinion," and he took a pinch of snuff with an air that suggested that he had finally settled the question once for all.

"I thank you, Sir Joseph," she replied, with a low curtsey. "I did hesitate, but I will hesitate no longer." And with another curtsey she retired to her own cabin, muttering to herself, "He little thinks how successfully he has pleaded his rival's cause!"

The Captain, who shared Sir Joseph's impression that Josephine had made up her mind to accept him, was over-joyed.

"Sir Joseph," said he, "I cannot express to you my joy at the happy result of your eloquence. Your argument was unanswerable."

"Captain Corcoran," replied Sir Joseph, "it is one of the happiest characteristics of this inexpressibly fortunate country that official replies to respectfully uttered interrogatories are invariably regarded as unanswerable."

And Sir Joseph, having discharged this mouthful of long words, withdrew to complete his night's rest.

Captain Corcoran could not conceal his exultation. Indeed, there was no reason why he should as he was entirely alone. He clasped his hands, smiled broadly, took a long breath of relief and had just begun to dance the hornpipe that Sir Joseph had taught him (to see if he remembered the steps) when he was interrupted by the unexpected appearance of poor deformed Dick Deadeye, who approached him with the irregular jerky action of a triangle that is being trundled like a hoop.

"Captain," whispered he, "I want a word with you!" And he placed his hand impressively on the Captain's wrist.

"Deadeye!" said he, "you here? Don't!"

"Ah, don't shrink from me, Captain!" replied Deadeye. "I'm unpleasant to look at and my name's agin me, but I ain't as bad as I look!"

"What do you want with me at this time of night?" said Captain Corcoran.

Deadeye looked round mysteriously to make quite sure that they were unobserved.

"I've come," said he, "to give you warning!"

"Indeed!" exclaimed the Captain, who was delighted to think that there was a chance of getting rid of Deadeye without hurting his feelings. "Do you propose to leave the Navy, then?"

"No, no," said Deadeye, "I don't mean that. Listen!"

The Captain was disappointed, but he listened, nevertheless.

And in accordance with the standing rule that no one was ever to say anything to the Captain that could be sung, Dick Deadeye struck up as follows:

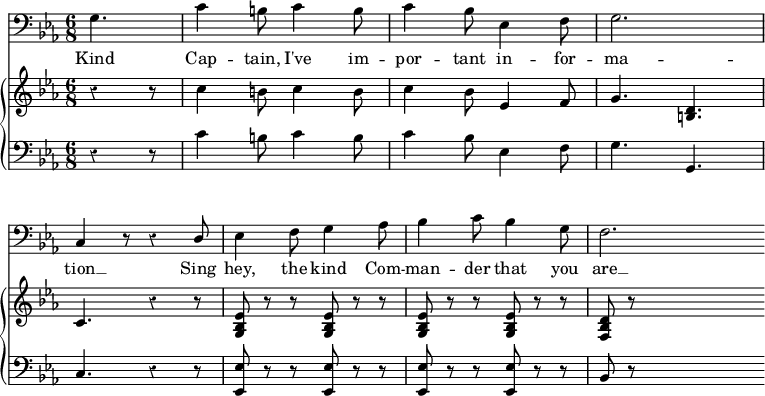

Kind Captain, I've important information

(Sing hey, the kind Commander that you are),

About a certain intimate relation

(Sing hey, the Merry Maiden and the Tar!).

The Captain (who had his book of rhymes handy, consulted it for a moment and then replied:

"DEADEYE!" SAID THE CAPTAIN, "YOU HERE? DON'T!"

Good fellow, in conundrums you are speaking

(Sing hey, the mystic sailor that you are),

The answer to them vainly I am seeking

(Sing hey, the Merry Maiden and the Tar!).

Of course the Captain was completely puzzled, having no idea what Deadeye was alluding to. So Dick explained:

Kind Captain, your young lady is a sighing

(Sing hey, the simple Captain that you are),

This very night with Rackstraw to be flying

(Sing hey, the Merry Maiden and the Tar!).

Good fellow, you have given timely warning

(Sing hey, the thoughtful sailor that you are),

I'll talk to Master Rackstraw in the morning!

(Sing hey, the cat-o'-nine-tails and the Tar!)

And, so singing, Captain Corcoran produced from his pocket a beautifully inlaid little presentation "cat-o'-nine-tails," and, as he flourished it, he brought it down accidentally (but heavily) on poor Dick's back. Dick, grateful for any attention, pulled his fore-lock respectfully and trundled off into the fore-part of the ship.

I ought to explain that the cat-o'-nine-tails is a cruel kind of whip with nine thongs, which was, at that time, commonly used in the Navy to punish badly behaved seamen, but Captain Corcoran was much too humane a man to use it. It happened to be in his pocket because it was a present from his dear old white-haired apple-cheeked grandmama which had only arrived that day.

Dick Deadeye had warned the Captain just in time; for as Dick crept off, the Captain saw a large body of the crew, with Ralph among them, advancing on tip-toe towards the boats which were hanging from irons, called davits, in the ship's side, and at the same time Josephine came out of her cabin with her hand-bag in her hand, and crept silently to where Ralph was standing. It was more than flesh and blood could stand, and, in the anger of the moment, the Captain exclaimed "Bother!" and brought the cat-o'-nine-tails down on the breach of a gun which happened to be handy.

All the crew were dreadfully startled.

"Why! what was that?" said Bob Buntline, one of the sailors who had not yet spoken.

"It was only the cat," said Bill Boom.

Bill Boom was perfectly right. It was the "cat."

As Josephine met Ralph, and while the crew were mustering on the quarter-deck, the Captain glanced hastily through his rhyming dictionary, and, having found what he wanted, revealed himself, exclaiming "Hold!"

Much alarmed and greatly astonished to find their Captain among them, they all held.

Captain Corcoran advanced and seizing his daughter by the hand twirled her away from Ralph Rackstraw, who looked like the Apollo Belvedere struck stupid.

Naughty daughter of mine (sang the Captain)

I insist upon knowing

Where you may be going

With these sons of the brine?

For my excellent crew,

Though foes they could thump any,

Are scarcely company

For a lady like you!"

Ralph wasn't going to stand this. He had been taught by the First Lord of the Admiralty that a British sailor is the finest fellow in the world, and if you can't believe a First Lord, whom can you believe? So, pulling himself together he began:

"Haughty Sir, when you address"—

"Poetry, please," said Captain Corcoran, "I allow no sailor to address me in prose."

Ralph thought for a moment, and then declaimed (in the key of G):

Proud officer, that haughty lip uncurl! (the Captain

uncurled his haughty upper lip as desired)

Vain man, suppress that supercilious sneer! (he

suppressed it at once)

For I have dared to love your matchless girl—

A fact well known to all my mess-mates here!

I, humble, poor, and lowly born,

The meanest in the port division—

The butt of epauletted Scorn—[1]

The mark of quarter-deck derision—

Have dared to raise my wormy eyes

Above the dust to which you'd mould me;

In manhood's glorious pride to rise,

He is an Englishman!

For he himself hath said it,

And it's greatly to his credit

That he is an Englishman!

For he might have been a Rooshian

A French, or Turk, or Prooshian,

![<< \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber #'stencil = ##f \new Staff { \time 4/4 \key d \major \clef bass \partial 4 \autoBeamOff d4 | d'4. gis8 gis4 gis | a2\fermata a4.( g!8) | \tempo "Moderato" fis4 d e g | fis8[( e]) a4 r a8. g16 | fis4 d e g | fis8([ g)] a4 r a8 a | b4 d' cis' b | a2 }

\addlyrics { He is an Eng -- lish -- man, For __ he him -- self has said it, And it's great -- ly to his cred -- it, That he is an Eng -- lish -- man! }

\new GrandStaff << \new Staff { \override GrandStaff.BarLine #'allow-span-bar = ##f \key d \major \relative g' { r4 | <gis e d>1\fz | <a e cis>2\fermata r | <fis d a>4\p^\markup { \italic "Moderato." } <d a>_\markup { \smaller { \italic stacc. } } <e d> <g cis, a> | << { fis8( g) a4 r a8. g16 } \\ { <d a>4 <cis a> <d a> <e a,> } >>

<fis d a> <d a> <e d> <g cis, a> | << { fis8( g) a4 r } \\ { <d, a>4 <cis a> <d a> } >> <a' fis d>

<b g d> <d b d,> <cis a d,> <b g d> | <a fis d>2 } }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key d \major r4 | <b, b,,>1 | <a, a,,>2_\fermata r | <d d,>4 <fis fis,> <a a,> <a, a,,> | \ottava #-1 \set Staff.ottavation = #"con 8va" d, e, fis, cis, | d, fis, a, a,, | d, e, fis, d, | g, g,, g,, b,, | \ottava #0 <d d,>2 } >>

>>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/g/ngjutw2qipkqfd51ift30r9pwa2k66v/ngjutw2q.png)

Or perhaps I-tal-i-an!

But, in spite of all temptations

To belong to other nations,

He remains an Englishman!

And when they had finished, all the crew wiped their eyes (which were full of manly tears), and shook hands with each other until their emotion had in some degree subsided. Indeed three or four of them were carried off in hysterics, and had to be revived with eau-de-Cologne, a tub of which always stood on the forecastle. Speaking for myself, I do not quite see that Ralph Rackstraw deserved so very much credit for remaining an Englishman, considering that no one seems ever to have proposed to him that he should be anything else, but the crew thought otherwise and I daresay they were right.

Captain Corcoran hardly knew how to act, for he so seldom got into a tearing rage that he didn't know what it was considered usual for a man in tearing rage to do. He was anxious not to overdo it, and at the same time he felt that it was necessary to let them know that a tearing rage was what he was in. After some reflection, and a glance at his dictionary, he concluded that the best way was to depart from his usual calm correct way of speaking, and horrify them by introducing some really unpardonable language. So he exclaimed:

In uttering a reprobation

To any British Tar,

I try to speak with moderation,

But you have gone too far.

I'm very sorry to disparage

A humble foremast lad,

But to seek your Captain's child in marriage,

Why, hang it, it's too bad!

Yes, hang it, it's too bad!

(I don't care, I will say it, and risk the consequences)—

Yes, hang it, it's too bad!

The crew were awestruck, for they had never, in all their experience of Captain Corcoran, known him to forget himself as far as to use an expression of this description. Three times too—not once, but three times, as if he revelled in his wickedness! And what made the circumstance more impressive was that as their amazement and agitation subsided, they saw the First Lord of the Admiralty standing, apparently thunder-struck, in their midst!

"I am appalled," said Sir Joseph, as soon as he could control his tongue. "Simply appalled!"

There was no mistake about it—he was quite white with the shock that the Captain's language no had given him. He was no longer a First Lord—he was a Monument of Pathetic Imbecility.

"To your cabin, Sir," said he, trembling with emotion, "and consider yourself under the strictest arrest."

"Sir Joseph," said Captain Corcoran, "pray hear me—"

"To your cabin, Sir!"

And a couple of marines marched him off under the command of the smallest midshipman in the ship.

Sir Joseph had by this time somewhat recovered his composure

"Now tell me, my fine fellow," said he, addressing Ralph Rackshaw, "How came your Captain so far to forget himself?"

"Please your honour," said Ralph, pulling respectfully at his forelock, "it was thus wise. You see I'm only a topman—a mere fore-mast hand—"

"Don't be ashamed of that," said Sir Joseph, "a topman is necessarily at the top of everything."

This, of course, was not the case, but Sir Joseph, having been a solicitor, did not know any better.

"Well, your honour," said Ralph, "love burns as brightly on the forecastle as it does on the deck, and Josephine is the fairest bud that ever blossomed on the tree of a poor fellow's wildest hopes!"

Sir Joseph could scarcely believe his ears.

"Are you referring to—er—Miss Josephine Corcoran?" gasped Sir Joseph.

"That's the lady, Sir," said Ralph, "in fact here she is, bless her little heart!"

And Josephine rushed into Ralph's outstretched arms.

"She's the figure-head of my ship of life—the bright beacon that guides me into the port of happiness—the rarest, the purest gem that ever sparkled on a poor but worthy fellow's trusting brow."

The crew burst into tears at this lovely speech and sobbed heavily. It had quite a different effect on Sir Joseph who, forgetting all his dignity, danced about the deck in a blind fury.

"You—you impertilent presumtiful, disgracious, audastical sommon cailor," exclaimed Sir Joseph, chopping up and transposing his letters and syllables in a perfectly ridiculous manner, "I'll teach you to lall in fove with your daptain's caughter! Away with him to the barkest bungeon on doard!" Of course he meant to say "the darkest dungeon on A COUPLE OF MARINES MARCHED HIM OFF UNDER THE COMMAND OF THE SMALLEST MIDSHIPMAN IN THE SHIP

Josephine clung to Ralph and declared that as he was to be shut up in a cell, she would go with him, but they were violently torn asunder, and, a pair of handcuffs having been placed on Ralph's wrists by the serjeant of the marines, he was taken away in custody. At this point Sir Joseph became calm and coherent again.

"And as for you, Miss Corcoran—" he began, but before he could say what he was going to say (whatever it was) Little Buttercup came forward, and exclaimed "Hold!"

"Why?" Sir Joseph asked, not unnaturally.

"Because I have a tale to unfold," she replied.

"We are all attention," said Sir Joseph." Proceed."

And Little Buttercup proceeded thus:

A many years ago,

When I was young and charming,

As some of you may know,

I practised baby-farming,[2]

The crew were most interested in this piece of news, and, expecting that she was about to reveal something that would entirely alter the aspect of affairs, they muttered to each other:

Now this is most alarming—

When she was young and charming

She practised baby-farming

A many years ago!

Two tender babes I nussed,

One was of low condition,

The other "upper crust,"[3]

A regular patrician!

Again the crew said to each other, by way of explaining how the case stood:

Now this is the position—

One was of low condition,

The other a patrician,

A many years ago!

This having been made quite clear to them, Little Buttercup continued the story:

Oh, bitter is my cup,

However could I do it?

I mixed those children up,

And not a creature knew it!

This was quite an inexcusable piece of carelessness on the part of Little Buttercup. If she had any doubt which was which, she could so easily have tied a bit of blue ribbon round the neck of one, and a luggage-label round the neck of the other. The sailors were surprised at this culpable neglect of duty and replied:

However could you do it?

Some day no doubt you'll rue it,

Although no creature knew it

So many years ago!

Little Buttercup, not heeding their interruption, concluded her confession thus:

In time each little waif

Forsook his foster-mother,[4]

The well-born babe was Ralph—

Your Captain was the other!!!

Again the crew explained the situation to each other, that there might be no mistake about it:

They left their foster-mother;

The one was Ralph, our brother,

Our Captain was the other,

A many years ago!!!

Here was a pretty kettle of fish! Ralph was, properly speaking, a Captain in the Navy, and Captain Corcoran was only a common sailor!

"Am I really to understand," said Sir Joseph, "that during all these years, each has been occupying the other's position?" "I MIXED THOSE CHILDREN UP"

"And you've done it very well," said Sir Joseph, and all the crew applauded so vigorously that Little Buttercup thought they wished to hear it all over again, and had actually got so far as "A many years ago," when Sir Joseph interrupted her:

"Let them both appear before me at once," said he.

And immediately Ralph appeared dressed in Captain Corcoran's uniform as a captain in the navy, and Captain Corcoran in Ralph's uniform as a man-o'-war's man!

This had been carefully arranged by Little Buttercup herself. Knowing that the time had come when it would be necessary that she should reveal her secret, she had previously caused one of Captain Corcoran's uniforms to be conveyed to Ralph's quarters, and one of Ralph's uniforms to be placed in Captain Corcoran's cabin, with a note, pinned to each bundle, explaining the condition of affairs. Now we see what Little Buttercup meant when she sang those mysterious lines to Captain Corcoran about things being seldom what they seem, skim-milk masquerading as cream, and so forth. Oh, she was a knowing one, I can tell you, was Little Buttercup!

As Corcoran (no longer a captain) stepped forward, Josephine rushed to him in amazement.

"My father a common sailor!" she exclaimed.

"Yes," said Corcoran, "it is hard, is it not, my dear?"

During this time Ralph was too much occupied in trying to catch sight of the two epaulettes which glistened on his shoulders, to attend to anything else.

"This," said Sir Joseph, "is a very singular occurrence, and, as far as I know, nothing of the kind has ever happened before. I congratulate you both."

Then, turning towards Captain Rackstraw, as we must now call him, he said (indicating Corcoran), " Desire that remarkably fine seaman to step forward."

"Corcoran," said Captain Rackstraw, "three paces to the front—march!" just as Corcoran, when he was a captain, had said to Ralph.

Corcoran, however, knew his rights, and wasn't going to stand being spoken to in this abrupt fashion.

"If what?" said Corcoran, touching his cap.

"I don't understand you," said Captain Rackstraw haughtily.

"If you please," said Corcoran, with a strong emphasis on the "please."

"Perfectly right," said Sir Joseph, "if you please."

"Oh, of course," said Captain Rackstraw, "if you please."And Corcoran stepped forward and saluted, like the smart man-o'-war's man that he was.

"You're an extremely fine fellow," said Sir Joseph, turning him round as he inspected him.

"Yes, your Honour," said Corcoran, who was still too good a judge to contradict a First Lord of the Admiralty.

"So," observed Sir Joseph, "it seems that you were Ralph and Ralph was you."

"So it seems, your Honour," said Corcoran, with a respectful pull at his forelock.

"Well," said Sir Joseph, "I need not tell you that, after this change in your condition, a marriage with your daughter will be out of the question."

"Don't say that, your Honour," replied Corcoran, "Love levels all ranks, you know!"

Sir Joseph was rather taken aback by being confronted with his own words. But, having been a solicitor, he was equal to the occasion.

"It does to a considerable extent," said Sir Joseph, "but it does not level them as much as that. It does not annihilate the difference between a First Lord of the Admiralty and a common sailor, though it may very well do so between a common sailor and his Captain, you know."“I see,” said Corcoran; "that had not occurred to me.”

“Captain Rackstraw,” said Sir Joseph, "what is your opinion on that point?”

“I entirely agree with your Lordship,” said Ralph, whose love for Josephine overcame all other considerations. “If your Lordship doesn't want her, I'll take her with pleasure.”

He said this because, fine fellow as he was, and deeply as he loved Josephine, he considered that it was his duty, as an officer in the Navy, to give Sir Joseph the first choice.

“Then take her, sir, and mind you make her happy.”

And Captain Rackstraw arranged with Josephine that they would go on shore at once and be married at once. Fortunately the clergyman was still waiting for them, although he had become rather impatient at the delay.

During this conversation, Corcoran had a word or two with Buttercup, who took that opportunity of revealing herself to him as one of the maidenly crew of the Hot Cross Bun of twenty years ago. He was greatly touched at the story of her faithful devotion to him, and determined to repay it."My Lord," said he to Sir Joseph, "I shall be quite alone when Josephine marries, and I should like a nice little wife to sew buttons on my shirt and mend my socks."

"By all means," said Sir Joseph. "Can you suggest anybody?"

Corcoran presented blushing Little Buttercup to Sir Joseph, who gave her sixpence on the spot as a wedding present. Little Buttercup was so touched by Sir Joseph's liberality that she burst into tears.

Corcoran, overjoyed, at once broke into song, adapting, on the spur of the moment, the well-known and familiar words with which he used to greet his crew every morning, thus:

I was the Captain of the Pinafore!

And all the crew chorused:

And a right good Captain too!

I commanded of you all,

I'm a member of the crew!

I shall marry with a wife

In my humble rank of life,

And you, my own, are she!

But, wherever I may go,

I shall never be unkind to thee!

CORCORAN PRESENTED BLUSHING LITTLE BUTTERCUP TO SIR JOSEPH, WHO GAVE HER SIXPENCE ON THE SPOT

What, never?

Replied he:

No, never!

The crew, more slyly still:

What, never?

And the Captain, whose experience of his former wife had taught him that even the most amiable married people will fall out occasionally, replied:

Hardly ever!

Hardly ever be unkind to thee!

And they all sang:

Then give three cheers and one cheer more

For the hardy seamen of the Pinafore!

For he is an Englishman,

And he himself hath said it,

And it 's greatly to his credit

That he is an Englishman!

For he might have been a Rooshian,

A French, or Turk, or Prooshian,

Or perhaps I-tal-i-an!

But, in spite of all temptations

To belong to other nations,

He remains an Englishman!

In short, there were general rejoicings all round. Lemon ice, shoulders of mutton, ginger-beer and meringues-à-la-crème were served out in profusion, and Sir Joseph, who happened to know a number of surprising conjuring tricks, brought a rabbit smothered in onions out of his left boot, to the intense delight of the crew. All the sisters and cousins and aunts of Sir Joseph tumbled out of bed as soon as they heard the news, and came on deck after a hasty toilette. A general dance followed in which Ralph and Josephine particularly distinguished themselves, and then they all went on shore that the clergyman (who had nearly grown tired of waiting and wanted to go home to his breakfast bacon) might join the happy couple in matrimony. Corcoran was married at the same time to Little Buttercup, and Captain Rackstraw most kindly gave him a week's leave that he and his wife might go and enjoy some sea-bathing at Ventnor.

Captain Rackstraw proved to be a most excellent Commander, and was just as much beloved as Captain Corcoran had been, while Corcoran took up Ralph's duties with enthusiasm, and became one of the smartest top-men on board. It is an excellent test of a man's character when he resigns himself with cheerfulness to a sudden change from dignified affluence to obscure penury, and I can't help thinking that, on the whole, he was a very fine fellow.

But still I do wish he had not made that very unfortunate remark about being related to a peer.

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

- ↑ The idea of Scorn wearing epaulettes is rather a fine figure of speech. I do not remember to have met it before.

- ↑ By 'baby-farming' she meant that she earned her living by taking in little children to nurse, while their Papas and Mamas were travelling on the Continent.

- ↑ A vulgar expression intended to imply that one of them belonged to a family of some social importance. It is not an expression that I can recommend for general use, but Little Buttercup wanted a rhyme for 'nussed,' and there was no other word handy that would do.

- ↑ That is to say, when their respective parents returned to England and reclaimed them.