The Story of the Flute/Chapter 11

CHAPTER XI.

THE FLUTE IN THE ORCHESTRA.[1]

Introduction of the flute into the orchestra—The flute and piccolo as used by the great composers—Bach—His obligatos—Handel—His flauto-piccolo—Flute and organ—Gluck—Haydn—The Creation—Symphonies—Mozart—Disliked the flute—Symphonies—Serenades—Operas—Concertos—Beethoven—His famous flute passages—Weber—Meyerbeer—Piccolo passages—Italian operatic composers—William Tell overture—Mendelssohn—Midsummer Night's Dream—Symphonies—Oratorios—Schubert—Schumann—Use by modern composers—Berlioz—Flute and Harp—Brahms—Dvǒrák—The Spectre's Bride—Cadenzas—Grieg—Bizet's Carmen—Sullivan—The Golden Legend—Coleridge-Taylor—Wagner—Tschaikowsky—R. Strauss—Passages of extreme difficulty.

The flute is the leader of the wood-wind, and if judiciously used is one of the most telling instruments, and is capable of producing a great varietyEarly

Instances

of its Use of effects. The earliest representations of an orchestra rarely include a flute or any kind, but one in a Breviary of the fifteenth century, now in the Brussels Library, contains two flutes-à-bec. Fifes and a flute were included in a band which played instrumental intermezzi at a performance of Ariosto's Suppositi before Pope Leo at the Vatican in 1518. Flutes were used, along with lutes, in Corteccia's ballet music at the marriage of Cosmo I. and Eleanora of Toledo in 1539; and in Baltazarini's Ballet Comique de la Royne the music of which was composed by Salmon and Beaulieu in 1581. In this work each character is always accompanied by special instruments (as also in Monteverde's Orfeo), those of Neptune being flutes and harp. In Cavaliere's oratorio Anima e Corpo, produced at Rome in 1600, the orchestra included two flutes, whilst in Jacopo Peri's Eurydice (December, 1600), the earliest Italian opera, three flutes behind the scene played a Ritornello, whilst Tirsi, a shepherd, pretended to play a triple flute ("tri-flauto") on the stage. Here is what he played, the longest piece of instrumental music in the entire opera!—

Peri, Eurydice.

Claudio Monteverde, who is generally termed the founder of the orchestra, in his opera Orfeo (1607-8), introduces an instrument described as "Uno Flautino alia Vigessima secunda," which would strictly mean an instrument pitched an octave above the piccolo! Probably all the flutes mentioned in the above works were flutes-à-bec, the "flautino" being a little high-pitched whistle pipe.

Alessandro Striggio is said to have employed a transverse flute (along with two flutes-à-bec—"Tenori de Flauti") in his La Cofanaria (1566). If so, he is to be credited with the first introduction of a transverse flute into the orchestra, a distinction usually attributed to Giovanni Battista Lulli, who beyond all doubt used the instrument in several of his operas, sometimes allotting it an independent part. Lulli has two such flutes in Alceste (1674), and gives solo passages along with bass in his Songe d'Atys (1676). In his Isis (iii.) two "German" flutes play in thirds in a minor key to

Lulli, Proserpine.

![\new GrandStaff <<

\new Staff = "flutes" \with {

instrumentName = "2 FLUTES."

midiInstrument = "Flute"

} <<

\new Voice = "first" \relative c'' {

\voiceOne

\key c \major

\time 3/4

r1*3/4

f4. e8 f4

d4. c8 d4

c2 c4

c b4. b8

b2 b4

\autoBeamOff

e4. d8[ c b]

a2 a4

d4. c8[ b a]

g2 g4

}

\new Voice = "second" \relative c'' {

\voiceTwo

\key c \major

\time 3/4

c4. b8 c4

a2 ais4

b2 b4

b a!8 g a4

\autoBeamOff

f4. f8[ g a]

g2 g4

c4. b8[ a g]

f2 f4

b4. a8[ g f]

eis2 eis4

}

>>

\new Staff = "bass flute" \with {

instrumentName = \markup \center-column {

"BASS FLUTE"

"(in sol)"

}

midiInstrument = "Flute"

} \relative c' {

\transposition g

\clef mezzosoprano

\key c \major

\time 3/4

e2.

a,~

a

a'4. g!8 a4

f4 fis2

g4. f!8 g4

e2.

f4. e8 f4

d2.

e4. d8 e4

}

>>

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/c/d/cdoga7gngebgzac155ofrdssj5cvwu2/cdoga7gn.png)

J. S. Bach, living under Frederick the Great, naturally paid considerable attention to the favourite instrument Bachof that monarch. The treatment of the flute by Bach and Handel is particularly interesting, owing to the fact that they lived at the period when the flute-à-bec was being gradually superseded by the transverse flute. They each make use of both kinds. Bach uses the flutes much more freely than Handel, and gives them much more difficult passages—many indeed require very considerable executive skill on the part of the performer. He frequently employs the entire compass of the transverse flute of that day, which Handel hardly ever does.

Many of Bach's cantatas have parts for one or two flutes. In these works we find almost every possible combination of the flute with the other instruments used, with one noticeable exception—viz., flute and bassoon, a combination very usual in Handel and Haydn. In the earlier works Bach uses the flute-à-bec. He hardly ever uses both it and the transverse flute in the same work, and never in the same piece. The probability is that both varieties of flute were played by the same performers. It has been suggested that the flutes and oboes were so played, but as they are frequently used together in the same piece, this cannot have been the case as a general rule, although undoubtedly many early flautists did also play the oboe.

Bach is fond of flute obligatos, and many (along with all varieties of voice, but chiefly with soprano) are to be found in these cantatas. Some of Bach's

Flute

Obligatos them are extremely florid and difficult, abounding in iterated notes and arpeggios. These obligatos are sometimes written for a single flute, sometimes for two flutes playing in unison or else playing independent parts. We often find two flutes and bass forming the sole accompaniment, whilst occasionally the organ alone Is combined with the two flutes. No. 170 contains an alto solo with a remarkable rapid obllgato on the flute and organ combined.

Bach often uses the flute to express the sentiments contained in the text. In No. 122 three flutes play a chorale (by Cyrlacus Schneegass) to represent Bach's

use of the

flute angels singing. In the cantata "O Holder Tag," at the words "Be silent, at the words "Be silent, flutes," they play weak, dying-away notes. He frequently introduces flutes when tears are referred to. Thus in the St. Matthew Passion, at the words "May the drops of my tears have agreeable perfume for thee," two flutes play passages like cascades of pearls.

Bach frequently combines oboes with flutes, often in unison, sometimes in harmony. He very rarely combines the flute with a single stringed instrument obligato, although the combination of flute and violin, or flute and violoncello piccolo (No. 115)—and also of flute and horn—are very occasionally to be met with in the cantatas. In the chorales to his Passions and elsewhere the flutes, first oboe, and first violins as a rule play the same part as the soprano voices—the flutes being an octave above the voices; but in some choruses the flutes play the same part as the tenor voices, just as in some of the instrumental portions they play along with the violas, the violins and oboes playing the top part. This treatment of the flute as a tenor instrument is very remarkable. He occasionally makes effective use of the low holding notes, and frequently writes passages on the low register, which, if played under modern conditions as regards the balance of strings and wind, would be quite inaudible. Probably he doubled them on the organ, or very possibly several flutes played the same part—a custom which was quite usual in early times; we frequently find the directions "All the first flutes," "All the second flutes." In order to obtain the proper balance of tone in the works of Bach's era the orchestra should contain nearly as many flutes as first violins. When played by the huge orchestras of to-day, many of the delicate wind passages in the works of the great composers of the past are completely drowned by the mass of strings—e.g., the flute turns in the first movement of Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony and the flute and bassoon passages in the finale to Mozart's Symphony in C.

I have only noticed two instances in the cantatas of the use of the "flauto piccolo" (probablyFlauto-

Piccolo

in Bach a small flute-à-bec); in No. 96 it is given a very florid part, without any flute; and in No. 103 it is employed to express the joy of the world, in the midst of which the flute interjects a short melancholy motif by way of contrast.

Bach has, in his flute parts, anticipated almost every device adopted by more recent composers, save that he

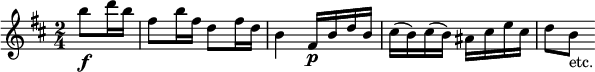

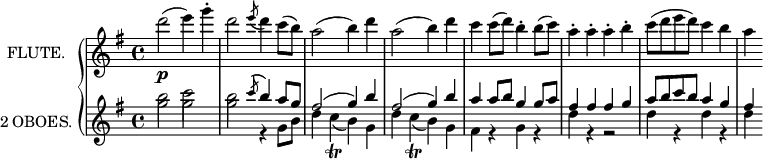

Bach, Suite in B minor.—Polonaise.

![\new GrandStaff <<

\new Staff = "flute" \with {

instrumentName = "FLUTE."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key d \major

\time 3/4

b16\mf d fis b

ais fis b fis

cis fis c( d32 e)

d'( cis b ais b16) fis

e32( fis g fis e d cis b

ais16) g' fis e

d32( cis b cis d e fis g

a!16) g32( fis) g16 d'

fis, d' e, cis'

d_"etc."

}

\new Staff = "bass" \with {

instrumentName = "BASS."

midiInstrument = "acoustic bass"

} \relative c' {

\transposition c'

\clef bass

\key d \major

\time 3/4

b8. d16 cis8 b ais8. b32 cis

b8. d16 cis8 b cis16 b ais cis

\autoBeamOff

b8.[ d16] cis8[ b a! g]

fis16_"etc."

}

>>

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/p/kp33tk5i2xgi4odnbvarct8oinhf3iu/kp33tk5i.png)

does not give it chromatic passages and uses accidentals very sparingly. He has used it to express grief, melancholy, softness, delicacy, feebleness, also as a pastoral instrument and expressive of joy and mirth; even occasionally to depict the supernatural and the anger of the Gods. He rarely introduces a flute into his purely instrumental writings. The Suite in B minor (which was a favourite with Mendelssohn), is for four strings and flute. The "Polonaise" in this work is for flute and bass only, the former being given a bravura variation; the flute is also very prominent in the bright "Badinerie." Bach has also written a concerto in F

Bach, ib. Badinerie.

major for flute, oboe, violin, and trumpet, two for flute, violin and clavier, and one for two flutes and clavier —all with string accompaniment.

Handel employs the flute much less frequently. Quite a large number of his operas and oratorios haveHandel no flute part; The Messiah, for instance (to which, however, Mozart has added a flute and also a piccolo part). In many works he introduces the flute in one or two numbers only; in none is it used anything approaching continuously throughout, as it often is by Bach. Handel's flute parts do not contain a single really difficult passage. Strange to say, his few "flauto piccolo" passages are harder and much more elaborate than those for the flute (he hardly ever uses both instruments together); the piccolo solo in Rinaldo being about the most difficult he ever wrote for any kind of flute. Handel rarely travels beyond the two octaves D′ to D′′′ of the flute

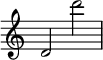

The famous obligato to "Oh, ruddier than the Cherry," in Acis and Galatea, has a rather interesting"Oh,

rudderier

than the

Cherry" history. In the first Italian version of the Serenata (1708) the flute-à-bec only is used, but this song does not occur in it, being first introduced in the English version published about 1720, where it is marked "flauto"—i.e., flute-à-bec. In the second Italian version (1732) we find the transverse flute used throughout,

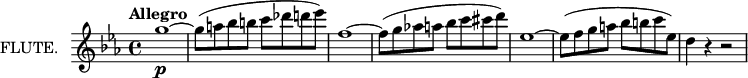

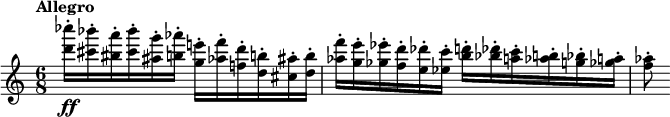

Handel, Acis and Galatea, "Oh, ruddier than the Cherry."

![\new Staff = "flute" \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key bes \major

\tempo "Allegro"

\autoBeamOff

g'8[\p d'16( c)] bes([ a) g( fis)] g8[ b,] a[ f']

g,[ bes'16( a)] g([ f) ees( d)] ees8[ ees'] f,[ d']

ees,[ g16( f)] ees([ d) c( b)] c8[ a'] bes![ g]

fis_"etc."

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/m/tmle80mftfg59gf1ukye4vdu2f5i61k/tmle80mf.png)

but again this song is omitted. When Mozart re-scored the work, he gave this obligato to a transverse flute, adding some beautiful and characteristic passages, whilst Mendelssohn allotted it to two flutes. At the Ancient Concerts (London) it used to be performed on a flageolet, but nowadays it is usually played on a piccolo; possibly by way of a joking reply to the monster Polyphemus' demand for a pipe for his capacious mouth! Surely if Handel had intended this he would have marked it "flauto piccolo." In this very work the florid accompaniment to "Hush,Handel's

Flauto-

Piccolo ye pretty warbling choir" was originally so marked, though it is now always played on a flute. (By the way, "The heart the seat of soft desire" was originally written for two flutes-à-bec). Handel used the "flauto piccolo" on several

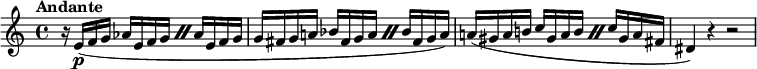

Handel, Acis, "Hush, ye pretty warbling choir."

![\new Staff = "flute" \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key f \major

\time 3/8

\tempo "Andante"

\omit TupletNumber

\omit TupletBracket

\autoBeamOff

\times 2/3 {

a'32([ bes c16) f,] f([ a) g] g([ bes) a]

a32[ bes c bes a g] f[ g a g f e] d16[ d' c]

bes32[ c d c bes a] g[ a bes a g f] e16[ g c,_"etc."]

}

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/r/5rl2tz14l9e5pdaja2h5xhpkzih710z/5rl2tz14.png)

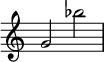

other occasions. The most notable of these is the very elaborate obligato and cadenza (which last is omitted in the later version of 1731) to Almirena's song, "Augelletti," in Rinaldo (1711). This part was marked "flageolet" in the original autograph score, but it was altered to "flauto piccolo" in Handel's own writing. Addison in The Spectator, Nos. 5 and 14, has a most amusing description of this scene as performed at the Queen's Theatre in the Haymarket, where sparrows flew about the stage and put out the candles; Addison calls the instruments used "flagellets and bird-calls." The "flauto piccolo" is allotted another very similar obligato in Riccardo (iii. 10). It is also used in the "Tamburino" in the ballet music in Alcitia (1735), whilst in the "Menuet" in the Water Music (1715) several "flauti piccoli" play in unison with the

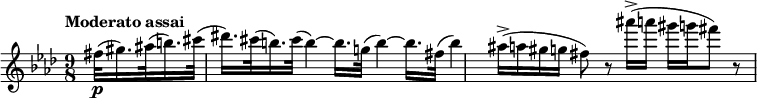

Handel's Rinaldo. Cadenza for Piccolo.

![\new Staff = "piccolo" \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\transposition c'

\key g \major

\tempo "Adagio"

\autoBeamOff

r4 r8 r16 d g8.[ d16 g8. d16]

\autoBeamOn

g16. d32 g16. d32

g d g d g d g d

e d c d e fis g a

fis e d e fis g a b

g fis e fis g a b c

a g fis g a b c d

b d c b a c b a

g b a g fis a g fis

e c' b c a b g a

fis g e fis d e c d

b d g d b d g d

c e g e c e g e

c e a e c e a e

d fis a fis d fis a fis

g b d b g b d b

fis a d a fis a d a

g b d b g b d b

a c a c a d c d

b c a b g b a g

g d e fis g a b c

d2~ d4~ d8. g,16

fis16. c32 b16. a32 a8. g16 g4\fermata

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/2/t297qv1ld5lb01fnor6ni9ieuka8z24/t297qv1l.png)

Several other flute obligates of note occur in Handel's works. Probably the best known is the soprano aria, "Sweet Bird," in Il Penseroso.Handel's

Flute

Obligatos The flute part is very florid and showy throughout, and an old critic has drawn attention to the admirable manner in which the words "Most musical, most melancholy," are treated. We have another bird-song in Joshua (1747), "Hark, 'tis the linnet [violin] and the thrush" [flute]. Apollo and Dafne has an important flute obligato to the duet, "Deh lascia." Like Bach, Handel uses the flute to convey the idea expressed by the words, as in "Softest sounds" in Athalia (i); with its thin string accompaniment, in order that the weak notes of the flute may not be drowned. Again, we find in Jephtha a remarkable flute obligato, "In gentle murmurs," and the words, "Tune the soft melodious lute, pleasant harp, and warbling flute," naturally are accompanied by a solo flute part, which instrument is also employed in solo passages and trills to illustrate "the soft-complaining flute" in St. Cecilia's Day,Flute and

Organ where the flute is used in combination with the lute and organ. The flute is introduced to represent tears in Deborah (iii. 5), "Tears such as fathers shed," being accompanied by two flutes and organ. This combination is also used in Alexander Balus, "Hark! he strikes the golden lyre," and in the famous "Dead March" in Saul. On one occasion when the present writer was playing at a public performance of this work, the second flute was horribly out of tune; at the conclusion of the number the second flautist discovered that he had left his bandana handkerchief (with which he cleaned his flute) in the tube all the time!

It has been pointed out that Handel uses the organ to accompany the flute in preference to the pianoforte, probably as being more similar in tone.Handel's

Treatment

of the Flute The combination of flute and bassoon, never used by Bach, also of flute and horn, occurs several times in Handel's works. In Solomon (1748) we find a curious obligato for a solo oboe, accompanied by all the flutes in unison. In La Resurresione and in Parthenope (iii. 6) the flute is used in conjunction with the Theorbo (bass lute). It is evident that, though he once declared that all flautists were intelligent, the flute is used by Handel more or less as an appendage to the orchestra rather than as a regular constituent member of it, the number of flutes employed being less than that of the other members of the wood-wind. Rousseau says Handel's usual orchestra contained but two flutes as against five oboes and five bassoons, and at the Handel commemoration in 1784 there were but six flutes, whereas the number of oboes and bassoons was twenty-six each. This preference for the double-reed tone is also very marked in Bach's writings, and even, though in a lesser degree, in those of Mozart. A notice in the General Advertiser of October 20th, 1740, announcing "a concerto for twenty-four bassoons, accompanied by a 'cello, intermixed with duets for four double-bassoons accompanied by a German flute," ridicules this predilection.

Many of Handel's flute passages were specially written for Karl Frederick Weidemann (said by Burney to have been a fine player), his principal flautist, who visited England about 1726.

Gluck seems to have been particulary fond of the flute and has written some lovely music for it. He has caught its true characteristics betterGluck than any other composer or his time. As a rule his flute passages are simple, though he writes freely up to the top G′′′ or even A′′′. In scenes of melancholy and grief he uses the solo flute with most telling effect. The most notable example is the famous scene in Orpheo, where he employs the flute to express the desolation and solitude of the bereaved Eurydice. This unrivalled passage has been thus described by Berlioz: "On voit tout de suite qu'une flûte devant seule en faire entendre le chant. Et la melodie de Gluck est conçue en telle sorte que la flûte se prête à tous les mouvements inquiets de cette doulour eternelle, encore emprunte de l'accent des passions de la terrestre vie. C'est d'abord une voix a peine perceptible qui semble craindre d'être entendue; puis elle gémit doucement, s'eleve a l'accent du reproche, à celui de la douleur profonde, au cri d'un cœur déchiré d'incurables blessures et retombe peu à peu à la plalnte, au gemissement, au murmure chagrin d'une âme résigneé. . . .quel poète!"

Gluck, Orpheo.

Gluck, Armide, ii. 3.

![\new Staff = "flute" \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key d \major

\time 2/2

\tempo "Andante"

d2~ d8 d( fis d)

d4 cis~ cis8 d( cis d)

e2~ e8 fis( e fis)

g2. \grace {fis8} e4

\grace {d8} cis2. e4

\appoggiatura {e8} fis2 d4 fis

g( fis8 e) a( g dis e)

a4( g8 fis) b( a eis fis)

\autoBeamOff

b([ a dis, e!)] b'([ a)] a16([ b c8)]

d2_"ect."

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/1/h/1h86g66lxo5epi4yf59rjfpucb5p5kq/1h86g66l.png)

ritornelle which "expresses the voluptuous languor of the soul of the hero under the seduction of the magician's art; we seem to see the lovely landscape, smell the perfume of the flowers, and hear the birds sing."[2]

Gluck was the first composer to discover the value and effectiveness of the sonorous, rich notes of the lowest register of the flute; striking examplesGluck's

use of the

Piccolo will be found in Alceste. As a rule these flute solos are accompanied by strings only. He is also one of the first writers to make use of the piccolo; he introduces it with dramatic effect in Iphigenie en Tauride (using it right up to the top G′′′), where we have double trills on two piccolos—as afterwards used by Weber and Meyerbeer.

Hitherto the flute had been used in a fitful manner, chiefly to produce special effects and for obligatos, but with Haydn and Mozart it becomes a regular and indispensable member of the orchestra, being frequently combined with other instruments and no longer almost exclusively confined to solo passages. Haydn evidentlyHaydn had a great predilection for the flute, and has written largely for it, using it much more freely than any of his predecessors. In fact, the wind instruments were only beginning to be understood by composers—as Haydn remarked pathetically to Kalkbrenner, "I have only just learned in my old age how to use the wind instruments, and now that I do understand them, I must leave them." Many of Haydn's symphonies have very prominent solo passages for the flute; especially in the slow movements. In a symphony composed in 1788 (Biedermann's ed. No. 3), the andante movement contains quite a long solo for the flute accompanied by two violins only. As the Esterhazy band included only a single flute-player (Hirsch was his name), Haydn often only uses one. Sometimes the flute is only introduced in a single movement, and is the only wind instrument used in that movement.

In The Creation we find several graceful flute solo passages; and in the lovely introduction to the third part, three flutes are used to depict the earthly paradise. The third flute was apparently to be played

Haydn, The Creation, "On Mighty Pens."

by the oboe-player, as it is written into his part. Macfarren has said of this passage, "The morning of

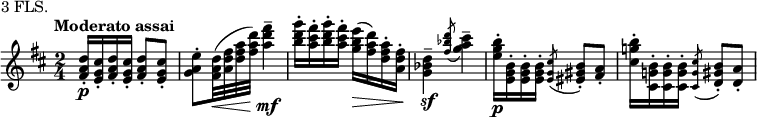

Haydn, The Creation. Opening, Part III.

![\new GrandStaff <<

\new Staff = "first" \with {

instrumentName = "1st FLUTE."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key e \major

\time 3/4

\tempo "Largo"

\autoBeamOff

b'2~\p b16([ \acciaccatura {cis16[ b ais]} b\< cis16. a!32)]\>

\autoBeamOn

a4(\sf gis16) r gis8(\p a b)

\autoBeamOff

cis([ \acciaccatura {dis16[ cis b!]} cis16. dis!32)] e4~\sf e16[ e,( gis b!)]

b8.([\> a16] gis8)\! r \bar "|"

}

\new Staff = "2nd & 3rd" \with {

instrumentName = \markup \center-column {

"2nd & 3rd"

"FLUTE."

}

midiInstrument = "flute"

} <<

\new Voice = "second" \relative c'' {

\voiceOne

\key e \major

\time 3/4

\tempo "Largo"

\stemDown

gis'4( fis e)

e~ e16 r \stemUp e4 e8

e4~ e16 b b' gis e8 b

\autoBeamOff

cis([ dis] e) r

}

\new Voice = "third" \relative c'' {

\voiceTwo

\key e \major

\time 3/4

\tempo "Largo"

e4( dis cis)

cis~ cis16 r d8( cis gis)

a4 gis4.~ gis8

\autoBeamOff

fis([ b] e) r

}

>>

>>

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/h/bhez3h1p2ih5oo0lawkrhbdqgl6cd60/bhez3h1p.png)

the world, with all the freshness and stillness of our loveliest summer-tide experience, might by such gentle sounds indeed be wakened to find the pulse"The

Creation" of nature vibrating in soft harmonies like priestly voices from the ancient statue [of Memnon] to greet its dawning." Haydn shows great skill in combining the flute with several other instruments; thus in the opening of his "Military" symphony we have one flute and two oboes playing quite long and delightfully fresh passages entirely alone. Duets for

Haydn, Military Symphony.

![{\clef treble

\override Staff.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f %hide the automatic time signature

\key bes \major

\autoBeamOff

r32 f'[ a' c''] ees''[ f'' a'' c'''] ees'''2}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/1/o12uc7d5p2yoitbq8bt50x7kilxsnu5/o12uc7d5.png)

The flute does not take nearly so outstanding a part in Mozart's music as it does in that of Haydn. He hardly ever gives it a solo of any lengthMozart or prominence. He does not consider it a necessary part of his orchestra: his first eight symphonies, and several others written quite late in life, and also his Requiem, have no flute parts. In each of his three great symphonies he only uses one flute. Apparently he shared the opinion of Cherubini, of whom it is related that once when a conductor, whose orchestra included only a single flute, complained piteously "What is worse than one flute in an orchestra?" the master replied laconically, "Two flutes"—meaning thereby that they are never in tune—or as the old German joke has it, "nothing is more dreadful to a musical ear than a flute concerto, except a concerto for two flutes."[3] As a matter of fact, Mozart did not like the flute and had a profound distrust of flute-players, for the same reason as that given by the Greek, Aristoxenus, who complained that the flutes of his day were continually shifting their pitch and never remained in the same state. The onlyHis dislike

of the flute flautist whom Mozart seems to have liked was one J. Wendling, of whom he said, "He is not a piper, and one need not be always in terror for fear the next note should be too high or too low; he is always right; his heart and his ear and the tip of his tongue are all in the right place, and he does not imagine that blowing and making faces is all that is needed; he knows too what Adagio means."

In several symphonies a flute is introduced into the slow movement only, and in the early works the flutesMozart's

Symphonies are generally in unison with the violins. The first symphony in which the flute has any independent part is the fourteenth. In the Twentieth Symphony we find a part marked "flute obligato" in the andante, but it is in unison with the first violins almost throughout.

In the Serenades the flute is much used. In the ninth the trio is for flute and bassoon (a very favourite combination with him), whilst the Rondo contains the nearest approach to a real flute solo in all Mozart. It is of quite considerable length and is accompanied by the strings. In another trio in this serenade Mozart's

Serenades a "flautino" (i.e. piccolo) is named along with two violins and bass, but no notes are written for it. In the fifth the two flutes have a great deal to do, and in one of the trios the second flute is given a solo accompanied by the strings.

Although Mozart never introduces the piccolo into any of his symphonies, we find it in several of hisHis Piccolo

Passages Operas, and above all in his Minuets and Dances. In a contre-danse entitled "La Bataille" the piccolo plays the part of Hamlet, whilst in another two piccolos play along with two oboes. Mozart uses the piccolo in these works in all sorts of combinations: sometimes it plays with the bassoons, sometimes with the violins, once with the lyre. Sometimes the piccolo plays the accompaniment along with the second violins, whilst the first violins and bassoon play the melody. In one dance we have a piccolo and two flutes playing together, and ending up with a solo piccolo run and shake. Mozart seems to have been fond of trying curious and unusual combinations: in his Twenty-seventh Symphony we find two flutes combined with the viola in thirds; in several we have passages for two flutes and two horns alone; the Fifth Divertimento is for two flutes (which play the melody), five trumpets, and four drums (in C, G, D, and A) only. This and another similar composition were written by Mozart whilst at Salzburg in 1774, probably for some special occasion.

The flute is again used along with the brass and drums in the finale to Act ii. of The Magic Flute with great effect to portray Tamino (originallyMozart's Operas acted by a flautist named B. Schack) with his flute overcoming the brute forces of Nature. This weird melody on the solo flute may be compared to the famous solo in Gluck's Orpheo.

Mozart, Magic Flute Overture.

Mozart has written two concertos for the flute—one was first performed by Cosel in 1774; the other was composed in 1778 for Deschamps, a rich Indian Dutchman who played the flute, and whom Mozart calls "a true philanthropist." Also a concerto in CHis

Concertos for flute and harp, a bright, melodious work with a fine andante. This last was written in 1770, when Mozart was at Mannheim, and had fallen in love with Aloysia Weber. The composer, though disliking both instruments, wrote the work at the request of the Duke de Guisnes (an amateur flautist) and his daughter, who played the harp. It is said that the Duke was niggardly in his payment. Mozart also wrote an Andante in C for the flute, with an accompaniment of oboes, horns, and strings; and two quartetts for flute and strings. The flautist Furstenau bears testimony to Mozart's perfect knowledge of the instrument, its technique, and easily-attained effects.

Beethoven's symphonies abound in fine flute passages, written with consummate skill; there is not one in which the flute has not something important to play. The Fifth Symphony has a curious passage of contrary motion for the flute, oboe, and clarinets; when this was first performed the audience

Beethoven, Fifth Symphony.

![\new GrandStaff <<

\new Staff = "flute" \with {

instrumentName = "FLUTE."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key aes \major

\time 3/8

\tempo "Andante con moto"

\partial 8 aes16(_\markup{\whiteout "dolce"} d

f8) f16( ees d f

aes8) aes16( g f aes

c8) c16( bes aes g

f8) f16( g aes bes)

c( bes aes g f g

aes bes c) c( bes aes

g4.) \omit Score.BarLine \omit GrandStaff.SpanBar

}

\new Staff = "oboe" \with {

instrumentName = "OBOE."

midiInstrument = "oboe"

} \relative c'' {

\key aes \major

\time 3/8

\tempo "Andante con moto"

\partial 8 r8

r4 aes16( d

f8) f16( ees d f

aes8) aes16( g f ees

d8) d16( ees f g)

aes( g f ees d ees

f g aes) aes( g f

ees4.) \omit Score.BarLine \omit GrandStaff.SpanBar

}

\new Staff = "clarinet" \with {

instrumentName = "2 CLARTS."

midiInstrument = "clarinet"

} \relative c'' {

\transposition bes

\key bes \major

\time 3/8

\tempo "Andante con moto"

\partial 8 r8

r1*3/8

r4 <bes d>16( <g bes>

<e g>8) <e g>16( <f a> <g bes> <a c>

<bes d>8) <bes d>16( <a c> <g bes> <f a>)

<e g>( <f a> <g bes> <a c> <bes d> <a c>

<g bes> <f a> <e g>) <c e!>( <d f> <e g>

\autoBeamOff

<f a>[ <g bes> <a c> <bes d>)]

}

>>

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/6/g/6gwnpv0ynesknwmxliuwr2vse96gkei/6gwnpv0y.png)

that known as "Langage des Oiseaux," at the conclusionThe

Famous

Passage

in the

"Pastorale" of the andante in the "Pastorale" Symphony, where, amidst the murmurs of the stream, we suddenly hear the voices of the cuckoo (clarinet), quail (oboe), and nightingale, the last-named being reproduced by a trilling passage on the flute. Grove says that these "imitations, or rather caricatures," were intended by Beethoven as a joke of the most open kind, and adds "how completely are the

Beethoven, Pastorale Symphony.

![\new Grandstaff <<

\new Staff = "flute" \with {

instrumentName = \markup \center-column {

"FLUTE."

"(Nightingale.)"

}

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key bes \major

\time 12/8

\tempo "Andante"

r4 r8 r4 f8~ f r f~ f r f(

\autoBeamOff

g)[ f] r g([ f)] r g([ f)] g16([\accent f)] g([\accent f)] g([\accent f)] g([\accent f)]

f1.\startTrillSpan

ees4.( f16)([\stopTrillSpan e] f8) r r2.

\partial 2 r4 f8~ f^\markup \right-column {"Phrase" "repeated."}

}

\new Staff = "oboe" \with {

instrumentName = \markup \center-column {

"OBOE."

"(Quail.)"

}

midiInstrument = "oboe"

} \relative c'' {

\key bes \major

\time 12/8

\tempo "Andante"

R1*12/8

r2. r4 r8 r r d'16. d32

d8 r r r4 d16. d32 d8 r r r4 d16. d32

d8 r d16. d32 d8 r r r2.

\partial 2 r2

}

\new Staff = "clarinet" \with {

instrumentName = \markup \center-column {

"CLARINET."

"(Cuckoo.)"

}

midiInstrument = "clarinet"

} \relative c'' {

\transposition bes

\key c \major

\time 12/8

\tempo "Andante"

R1*12/8

R1*12/8

e8 c r r4 r8 e c r r4 r8

e c r e c r r2.

\partial 2 r2

}

\new Staff = "violin" \with {

\RemoveAllEmptyStaves

instrumentName = "VIOLIN."

shortInstrumentName = "VIOLIN."

midiInstrument = "violin"

} \relative c'' {

\key bes \major

\time 12/8

\tempo "Andante"

R1*12/8

R1*12/8

R1*12/8

r4 r8 r4 bes8(\p \grace {bes8} a)( g f) f( g a)

\partial 2 bes r r4

}

>>

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

short-indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/e/u/eumpnc9u7soaxxbzee6d7djomkbf9fa/eumpnc9u.png)

"At last the brook is still, the trees rustle no more: we have already once said farewell to the soft babbling that long kept us spell-bound. Quail, cuckoo, and nightingale are alone still heard.—Beautifully imagined! as it were also saying 'farewell' to the sympathetic wanderer up the vale; who, only another human form of them, had stayed so long with them, loving them like their brother, enchanted by their song—enchanted in Nature's bosom."

An American critic dissects the passage more coldly:—

"Neither the nightingale, the quail, nor the cuckoo sings precisely thus. The nightingale does not imitate itself in the proportions of the musical scale; it only makes itself heard by inappreciable or variable sounds, and cannot be imitated by instruments of fixed intervals and absolute pitch. The quail has been well rendered as to its usual rhythm, but not in relation to its pitch and quality. As to the cuckoo, it gives the minor third, not the major."

At the conclusion of the opening movement of this symphony the flute is given a very dainty and characteristic ascending passage, the rest of the orchestra being

Beethoven, Pastorale Symphony.

![\new Staff \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key f \major

\time 2/4

\tempo "Allegro non troppo"

f8\p g_\markup {\italic "dolce"} a( bes16 a)

g8\staccato a\staccato bes( c16 bes)

a8\staccato bes\staccato c( d16 c)

\autoBeamOff

bes8[ c d e]

f r r4

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/m/qmmc00eqc7htqchj41wcltop42yvvuz/qmmc00eq.png)

Beethoven with fine effect. Beethoven was the first to introduce this instrument into a symphony, and he uses it also in the Fifth and

Ninth Symphonies ("like golden braid on tapestry, lending dazzling glitter to the design"), in the overture to Egmont, in his Ruins of Athens, King Stephen, and

Beethoven, Overture to Egmont.

the "Battle" Symphony (op. 94), where he assigns to it "Rule Britannia" and "Marlbrook," the latter in a minor key to typify that the French were defeated. He never uses two piccolos.

In the overture Leonora, No. 3, the flute plays an ascending scale from the low D upwards, followed by aThe Passage

in "Leonora,

No. 3" gay succession of rapid sequences in the upper register. This very prominent passage is written for the first flute only. Owing to the weakness of the low register of the flute, the earlier portion of the ascending scale is not heard as a rule.

On one occasion a very celebrated conductor at a rehearsal of this work desired all three flutes to play the scale in unison. The first flautist refused to allow this, on the ground that Beethoven wrote it for one

Beethoven, Overture, Leonora, No. 3

flute only, and that it must be so played. Both were obstinate on the point, a quarrel ensued, and the first flute soon after threw up his post.

Weber may almost be said to have inaugurated a new era in scoring for the wood-wind. His treatment of the flute in Der Freischültz is very remarkable.Weber Berlioz says of the sustained notes in "Softly sighs": "There is something ineffably dreamy in these low holding notes of the two flutes, during the melancholy prayer of Agltha, as she contemplates the summits of the trees silvered by the rays of the night

Weber, Der Freischütz, "Softly sighs."

Weber, Der Freischütz.

veiled and gloomy impression, and later on to express agitation. In Oberon (ii) the flute is used to create a fairy effect, the first flute and first clarinet playing the melody, whilst the second flute and second clarinet play arpeggios with contrary motion. Weber is fond of arpeggios on the flute and also of blending the flutes and clarinets together. He very frequently uses the flute in unison with the voice. In Euryanthe, when the heroine is deserted in the forest, it is the flute that voices her desolation. He also makes full use of the middle and upper registers, and has written many bright and florid flute passages:—e.g., the overture to

Weber, Preciosa Overture.

![\new Staff \with {

instrumentName = "FLUTE."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\time 3/4

\tempo "Allegro moderato"

\override TupletBracket.tuplet-slur = ##t

\override TupletBracket.bracket-visibility = ##t

\override DynamicTextSpanner.style = #'none

\autoBeamOff

r4 r \tuplet 3/2 8 {a16([\p b c)] c([ d e)]}

e4(\accent c) \tuplet 3/2 8 {c16([ d e)] e([ fis g)]}

g4(\accent e) \tuplet 3/2 8 {e16([\cresc fis g)] g([ a b)]}

\autoBeamOn

c8\f c16\staccato c\staccato c8\staccato c\staccato \acciaccatura {d8} c16( b c e)

d2\> g,8. g16\!

\autoBeamOff

e'8[ \tuplet 3/2 8 {e16( d c)] d([ c b)] c([ b a)] b([ a g)] a([ g fis)]}

\autoBeamOn

fis8.\trill e16 dis4 b'8 \tuplet 3/2 {b16\staccato b\staccato b\staccato}

b4.( a16 gis) gis( fis) e\staccato dis\staccato

e8 \tuplet 3/2 {e'16\staccato e\staccato e\staccato} e4. r8_"etc."

}

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/6/q6nsbopnq6ptsubxbqx7tzknpvekbse/q6nsbopn.png)

Preciosa. The flute is very prominent throughout all his operas—he writes well for it and gives it good, full, and melodious parts; I would instance Killian's song in the first scene of Freischültz, where the flute plays a

Weber, Der Freischütz. Killian's Song.

Weber, Der Freischütz. The Hermit's Song.

lively little tune in octave with the solo 'cello, and the Hermit's song in the finale of the same opera; the

Preciosa, ii, Lied No. 6.

![\new Staff \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key d \major

\time 6/8

\tempo "Larghetto. (Auf dem Theater.)"

fis'8.(\p cis16 d gis,) a8.( eis16 fis cis)

d a d fis a d fis4.\fermata

r4 r8 r16 d,16(\staccato fis\staccato a\staccato d\staccato fis)\staccato

g4 r8 r16 g16(\staccato e\staccato c\staccato a\staccato g)\staccato

fis8 r r r16 a,( g' e a g)

\autoBeamOff

fis([ a d8)] e16([ fis] g[ dis e e, a g]

\autoBeamOn

fis4) r8 r16 g,16 b d g b

e4. r16 a,, cis e a cis

d4( b16 g fis4 d8)

cis8( a16 g e8) e4( d8)

\autoBeamOff

d16([ a' fis d' a fis')] a16.([ d32] fis8.[ d16)]

\autoBeamOn

cis4.(\trill \grace {b16 cis)} d4 r8

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/c/h/chddby6sax7be611dh7xhu0g65ztqmr/chddby6s.png)

lovely woodwind passage at the opening of the third scene in Preciosa, the Lied, No. 6, in the same, and the

Weber, Oberon, Finale, Act II., " Let us sail over the sea."

Weber, Overture to Oberon.

![\new Staff \with {

instrumentName = "FLUTES."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key d \major

\tempo "Adagio"

\autoBeamOff

r2\ppp <cis' e>32[\staccato <g bis>\staccato <g cis>\staccato <f gis>\staccato]

<e a>\staccato[ <cis g'>\staccato <a e'>\staccato <g cis>\staccato] <e a>16 r r8

r2 <a' d>32\staccato[ <d, gis>\staccato <d a'>\staccato <b eis>\staccato]

<a fis'>[\staccato <g cis>\staccato <fis d'>\staccato <fis a>\staccato] fis16 r r8

}

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/1/q/1q2cl30tza3j0gx37u7mnq2tamyqnhf/1q2cl30t.png)

I have dwelt at some length on Weber, as his writings show a more complete grasp of the possibilities of the flute than those of any of his predecessors;Weber's

use of the

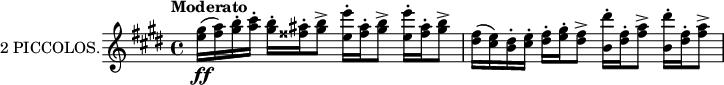

Flute I might almost add, than most of his successors. Moreover, they are most grateful to the player, are eminently playable, and present no great difficulties of execution. He also uses the piccolo in a very original manner to produce a startling and weird effect, as in the ghost scene in

Weber, Der Freischütz. Caspar's song.

![\new Staff \with {

instrumentName = "2 PICCOLOS."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\transposition c''

\key d \major

\time 2/4

\tempo "Allegro feroce"

\autoBeamOff

r4 <gis' b>\accent\trill

<fis a>8([ \grace {d'16[ e]} <d fis>8)] <gis, b>4\accent\trill

<fis a>8([ \grace {d'16[ e]} <d fis>8)] r4

}

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/2/527i1vf4h79a4nuppd4b9idyfnazw1i/527i1vf4.png)

Freischütz and in Caspar's drinking song, The mocking effect of the shakes on two piccolos is termed by Berlioz a "diabolic sneer," and "a fiendish laugh of scorn" when repeated at the words "Revenge, thy triumph is nigh." But Weber does not always employ the piccolo in this manner. We find two piccolos used in the Bridal March in Euryanthe, in Oberon, and in Preciosa (ii.), where they have a remarkable passage. In the

Weber, Preciosa, Opening Chorus, 2nd Act.

last-named opera (sc. viii.) we have the piccolo combined with the clarinet, with an accompaniment of bassoon, horns, drums, triangle, and tambourine—no strings. Another curious combination occurs in the Cantata on Waterloo, where the Grenadier's March is written for two piccolos and side drums only, along with the voices.

Meyerbeer was very fond of the piccolo, especially in scenes of devilry, and introduces it largely into all hisMayerbeer

and the

Piccolo operas. Thus in Robert le Diable it is largely used in the Baccanale and the Valse Infernale (i.) and in the frantic dance of the condemned nuns (iii.). In the Couplets Bachiques in Le Prophete (v.) a telling effect is produced by a few piccolo notes, along with harps and flutes, and in the Benediction of the Daggers in Les Huguenots it creates an almost savage effect, where at the word "strike" it represents the clinking of iron. In Robert le Diable it represents the whistling of bullets. In Dinorah lightning is imitated by means of an ascending scale on the piccolo, the flute playing a descending scale in the opposite direction. In his Kronungs March we find two piccolos

Meyerbeer, Robert le Diable, Valse Infernale (for voices, piccolo, trumpets and cornets, trombones, tuba, triangle and cymbals).

![\defineBarLine ":" #'(":" ":" ":")

\new Staff \with {

instrumentName = "PICCOLO."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\transposition c'

\key d \major

\time 3/4

\tempo "Allegro moderato"

\autoBeamOff

\bar ":"

\repeat volta 2 {

\acciaccatura {e'8} d8*2[\ff \acciaccatura {e8} d8*2 \acciaccatura {e8} d8*2]

}

\acciaccatura {cis8} b8*2[ \acciaccatura {cis8} b8*2 \acciaccatura {cis8} b8*2]

\autoBeamOn

\tweak text "three times"

\tweak direction #UP

\startMeasureSpanner

fis'32*2(\sf g fis g fis g fis g fis g fis g)

\stopMeasureSpanner

\autoBeamOff

fis16*2([ e)] d8*2[\staccato cis]\staccato

b r

}

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

\context {

\Staff

\consists Measure_spanner_engraver

}

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/e/8/e8u3ft7jtl6lv7125keq8ksv31og0rm/e8u3ft7j.png)

and two flutes all playing separate parts simultaneously. Two piccolos and two flutes soli are used in L'Êtoile du Nord, and in the Soldiers' March there are four piccolos on the stage, but they play only two distinct parts. In

Ib. Dance of the Nuns.

the overture to Dinorah we again find two piccolos and two flutes used. He frequently uses the piccolo without the flute, and sometimes in very curious combinations—e.g., with the cor anglais or with the bass clarinet. "Piff", paff," sung by the soldier Marcel in The Huguenots (i.) is accompanied solely by the piccolo, cymbals pianissimo, four bassoons, big drum, and double bass pizzicato; the piccolo, as an introduction, shaking successively on G, G♯, A, and B. This song gave rise to Rossini's sarcastic comment, "musique champetre." In the finale to Act I. we find the piccolo, viola, bassoons, and trombones united; in the Bohemian rondo (act iii.) we have the piccolo, flute, drum de basque, and triangle; also the piccolo, trumpet, drums, and horns. In the valse in L'Êtoile (ii.) we have the piccolo, bassoon, 'celli, and double-basses: and in the gallop in Le Prophéte the piccolo, flute, and triangle have a very important solo passage.

Meyerbeer's treatment of the flute is masterly. He uses it largely to brighten the strings; bringing out allMeyerbeer's

Use of

the Flute its charm and sweetness, all its descriptive and dramatic powers. In the dream scene in Le Prophéte a mystical effect is produced by the low notes of the flute (right down to lowest C), accompanied by violins playing arpeggios, drum, and cymbals. In "L'Exorcisme" (iv.) two flutes and a piccolo are used along with violas, divided violins, and a cor anglais to create an ethereal effect at the words, "Que la sainte lumiére descende sur ton front." In the prelude to the song, "Quand je quittais la Normandie," in Robert le Diable, the flutes, in conjunction with the oboes and clarinets, are most delightfully handled, echoing and interlacing each other, as it were. In Les Huguenots the flute has many florid solo passages, and is given a long cadenza in the prelude to Act II. He frequently combines the flute with the harp, and in Dinorah (ii.) produces a peculiar effect by means of the flute and some harmonic sounds of the harp, which are heard above the melody which is sung out by the 'cellos.

The solo "Dall' Aurora," in L'Êtoile du Nord, is accompanied by a double obligato on two flutes—one flute is behind the scene and the other is on the stage, and has a cadenza along with the voice. Chorley remarks that this trio is "better as a concert-piece

Meyerbeer, Cadenza in Les Huguenots ii.

![\new Staff \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key g \major

\time 12/8

\tempo "Andante cantabile"

\override TupletBracket.bracket-visibility = ##f

d4( e16 d) cis( d g b d g) b,,4( c16 b) ais( b d g b d)

g,,4( a!16 g) fis( g b d g b) d,,2.*2/3\fermata_\markup \center-column {"chromatic" "scale."}\glissando eis''4

fis16( d) d\staccato d\staccato cis\staccato e\staccato

d( b) b\staccato b\staccato ais\staccato c\staccato

b( g) g\staccato g\staccato fis\staccato a\staccato

g( d) d\staccato d\staccato cis\staccato e\staccato

d4(\trill \tuplet 3/2 {g16 b d)}

b,4(\trill \tuplet 3/2 {d16 g b)}

g,4(\trill \tuplet 3/2 {b16 d g)}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {b( g d g d b d b g)}

d4.\fermata

\omit TupletNumber

\autoBeamOff

\grace {\tuplet 3/2 8 {fis16[ e d] a'[ g fis] c'[ b a] fis'[ e d] a'[ g fis] c'[ b a]}} ees'4 d8

d,,4.\fermata

\grace {\tuplet 3/2 8 {fis16[ e d] a'[ g fis] c'[ b a] fis'[ e d] a'[ g fis] c'[ b a]}} e'4 d8

d,,2. \grace {fis4 a \stemDown d fis a d fis a fis d a fis d \stemUp a fis d \stemNeutral} fis4.\trill\fermata e'4 d8

g,2 \bar "|"

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/5/d5fro0vd3d65fdzr7wj8te8jfpmd549/d5fro0vd.png)

than when heard in the opera, because there the songstress must remain at such a distance from both instruments (the flautist on the stage being merely a mime) that all the intimacy of response and dialogue is lost, and the effect is that of a soprano scrambling against a double echo." It was performed at the Philharmonic Concerts in 1857 (Pratten and Card) and in 1868 (Svendsen and Card), and by Madame Albani and Messrs. Fransella and Warner-Hollis at the Norwich Festival of 1899. Bach has accompanied a soprano aria with two flutes in several of his works, and Verdi accompanies the soprano and contralto voices in his "Agnus Dei" (Requiem) with three flutes: these, however, are not, strictly speaking, obligatos.

The Italian operatic composers, Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini, etc., write melodious passages for the flute,Italian

Operatic

Composers often in unison with the voice or the violin. A notable obligato occurs in the mad scene in Lucia de Lammermoor, which has given rise to the remark that whenever the principal female character in opera becomes distraught with passion or grief, her recovery is marked by a flute

Rossini, Overture, Scmiramide.

obligato! Rossini frequently combines the flute with the oboe or clarinet in rapid passages; as in the overtures to La Gazza Ladra and Semiramide, in the latter the above well-known passage is given first to the piccolo and oboe together, then to the flute, and finally to both flute and piccolo.[4] Rossini does not use the piccolo very much, he, however, introduces two in The Bather of Seville at the words "Point de bruit"—probably a joke. He seldom gives the flute a solo of any length; several, however, occur in William Tell. The Andantino in that overture is the best known flute passage in the whole range of orchestralThe

"Willian

Tell"

Overture music; the flute playing a florid embroidery, as it were, to the Alpine "Ranz des Vaches" on the cor anglais. This passage stands out wonderfully: I have seen a first-rate player from the Hallé orchestra actually trembling with nervousness when he approached it. After the final sustained top G had died away into nothing, he remarked to me, "I never come to that passage without shaking all over like an aspen leaf; if

Rossini, Overture to William Tell.

![\new GrandStaff <<

\new Staff = "flute" \with {

instrumentName = "FLUTE."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key g \major

\time 3/8

\tempo "Andantino"

\override TupletBracket.bracket-visibility = ##f

\autoBeamOff

r1*3/8

r8 d4~

\omit TupletNumber \tuplet 3/2 8 {d32[ fis\staccato a\staccato b\staccato a\staccato fis]\staccato}

\undo \omit TupletNumber \tuplet 3/2 8 {d[ d d d d d]}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {d[\staccato e\staccato fis\staccato g\staccato a\staccato b]\staccato}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {a[\staccato fis\staccato d\staccato d\staccato d\staccato d]\staccato}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {d8.:32\staccato}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {d32\staccato[ e\staccato fis\staccato g\staccato a\staccato b]\staccato}

}

\new Staff = "cor anglais" \with {

instrumentName = "COR ANGLAIS"

midiInstrument = "english horn"

} \relative c'' {

\transposition f

\key d \major

\time 3/8

\tempo "Andantino"

\override TupletBracket.bracket-visibility = ##f

\autoBeamOff

\tuplet 3/2 8 {a16[ b cis] d[ e fis] g[ b, g']}

\omit TupletNumber

\tuplet 3/2 8 {fis[ a, fis'] e[ g, e'] d[ fis, d']}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {cis[ a cis] e[ g8] fis16[ d8]}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {cis16[ a cis] e[ g8] fis16[ d8]}

}

>>

\layout {

indent = 3\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/4/a/4a01osna4vx9xjy8imj12l1uao1fsmf/4a01osna.png)

![\new GrandStaff <<

\new Staff = "flute" \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key g \major

\time 3/8

\override Staff.TimeSignature.color = #white

\override Staff.TimeSignature.layer = #-1

\override TupletBracket.bracket-visibility = ##f

\omit TupletNumber

\autoBeamOff

\tuplet 3/2 8 {a'32[\staccato fis\staccato d\staccato fis\staccato a\staccato d]\staccato

a[\staccato fis\staccato d\staccato fis\staccato a\staccato fis']\staccato

a,[\staccato fis\staccato d\staccato fis\staccato a\staccato a']\staccato}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {g([\staccato fis\staccato f\staccato e\staccato ees\staccato d]\staccato

cis[\staccato c\staccato b!\staccato bes\staccato a\staccato g]\staccato

fis[\staccato e\staccato d\staccato c\staccato b\staccato a)]\staccato}

g8 r r

\repeat volta 2 {

\tuplet 3/2 8 {r32 \grace {a32[ g fis]} g[ d' b g' d] b'[ g d g b, d] r g[ b, d g, b]}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {r \grace {a32[ g fis]} g[ d' b g' d] b'[ g d' b g' d] r e[ c g e c]}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {r b'[ g b d, g] b,[ d g, b d, g] r e'[ g' e, e' e,]}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {r d[ d' b, b' g,] g'[ d, d' b g d] r d'[ c' a fis a]}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {r \grace {a32[ g fis]} g[ g' d, d' b,] b'[ g, g' b, b' d,] d'[ b, b' g, g' d,]}

d'4.\trill

}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {r32 g,[\staccato d\staccato g\staccato b\staccato d\staccato]} g4~

\tuplet 3/2 8 {g32[ d, g b d g]} b4~

\tuplet 3/2 8 {b32[ g,\staccato b\staccato d\staccato g\staccato b\staccato]} d4~

\tuplet 3/2 8 {d32[ b, d g b d]} g4~

g4.~ \bar "||"

\revert Staff.TimeSignature.color

\revert Staff.TimeSignature.layer

\time 2/4

g8 r r4

}

\new Staff = "cor anglais" \with {midiInstrument = "english horn"} \relative c'' {

\transposition f

\key d \major

\time 3/8

\override Staff.TimeSignature.color = #white

\override Staff.TimeSignature.layer = #-1

\override TupletBracket.bracket-visibility = ##f

\autoBeamOff

\tuplet 3/2 8 {cis16[ a8] cis16[ a8] cis16[ a8]}

a'4.(

\tuplet 3/2 8 {a,16[ b cis] d[ e fis] g[ b, g')]}

\repeat volta 2 {

d8[~ \tuplet 3/2 8 {d16 e a,] d[ fis a,]}

d8[~ \tuplet 3/2 8 {d16 e fis] g[ a b]}

a8[~ \tuplet 3/2 8 {a16 d, e] f[ d e]}

fis!8[~ \tuplet 3/2 8 {fis16 e d] e[ a, a']}

d,8 r r

e8[~ \tuplet 3/2 8 {e16 fis b,] e[ fis a,]}

}

d8[~ \tuplet 3/2 8 {d16 a' fis] d[ a fis']}

d8[~ \tuplet 3/2 8 {d16 a' fis] d[ a fis']}

d8[~ \tuplet 3/2 8 {d16 a' fis] d[ a fis']}

d8[~ \tuplet 3/2 8 {d16 d' a] fis[^\markup {\italic "dim."} d a']}

\tuplet 3/2 8 {fis([ d a'] fis[ d a'] fis[ d a']} \bar "||"

\revert Staff.TimeSignature.color

\revert Staff.TimeSignature.layer

\time 2/4

fis8) r r4

}

>>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/z/lzei60uy81xa7k81p76ca8w63gqk9tq/lzei60uy.png)

Mendelssohn has given very considerable prominence to the flute, and writes most delightfully for it. His Midsummer Night's Dream music—inMendelssohn's

"Midsummer

Night's

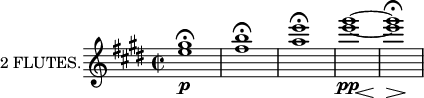

Dream which one writer says the composer has exhausted the resources of the instrument—contains quite a number of fascinating flute passages. In the very first bars of the overture he makes a very striking effect by means of slow ascending chords sustained by two

Mendelssohn, Midsummer Night's Dream Overture.

flutes; the delicate, elfin-like scherzo contains one of the most famous flute passages ever written—namely, the concluding rapid staccato passage (Mendelssohn was one of the first to introduce such passages for the wind) lying in the middle and lower registers, and descending to the low C♯. Mendelssohn fully appreciated the value of this lower register, and frequently made use of it. The words "Spotted snakes" have a curious triplet accompaniment for two flutes in unison on the low D

Mendelssohn, Midsummer Night's Dream, Scherzo.

![\new Staff \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key bes \major

\time 3/8

\partial 8 d,8 \bar ""

g16\staccato bes\staccato c\staccato d\staccato e\staccato fis\staccato

\autoBeamOff

g[\staccato d\staccato c\staccato bes]\staccato a[\staccato g]\staccato

\autoBeamOn

c\staccato d\staccato ees\staccato c\staccato d\staccato ees\staccato

f\staccato ees\staccato d\staccato c\staccato bes\staccato aes\staccato

g\staccato aes\staccato bes\staccato g\staccato aes\staccato bes\staccato

c\staccato d\staccato ees\staccato c\staccato d\staccato ees\staccato

fis\staccato a\staccato c\staccato bes\staccato a\staccato g\staccato

fis\staccato ees\staccato d\staccato c\staccato bes\staccato a\staccato

g\staccato bes\staccato c\staccato d\staccato e\staccato fis\staccato

\partial 8 g8 \bar "||"

g,16\staccato d\staccato cis\staccato d\staccato e\staccato fis\staccato

g\staccato d\staccato e\staccato fis\staccato g\staccato a\staccato

bes\staccato fis\staccato g\staccato a\staccato bes\staccato c\staccato

d\staccato bes\staccato c\staccato d\staccato e\staccato fis\staccato

g\staccato d\staccato e\staccato fis\staccato g\staccato a\staccato

bes\staccato a\staccato g\staccato a\staccato bes\staccato c\staccato

d8\staccato c16\staccato bes\staccato c\staccato a\staccato

bes8\staccato g\staccato d\staccato

g,\staccato r r

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/o/dozgrkmvod9jlixozynjgg88qgac33q/dozgrkmv.png)

and E, and at the words "Beetles black approach not near" they shake on the low C♮ and E respectively with thrilling effect. In the Nocturne we find most charming

Mendelssohn, Midsummer Night's Dream, Nocturne.

writing for the flutes; notice the effective shakes. Mendelssohn is continually giving delicate little trills to the flutes—e.g., the scherzo in his "Reformation" Symphony. The finale of this symphony appropriately opens with the German chorale "Eine feste Burg ist unser Gott" in G major (in its originalHis

Symphonies form, and not as used by Bach and Meyerbeer) on the first flute absolutely alone. "The grand old air thus heard alone and on one instrument comes like a response from the skies [to the prayer in the preceding andante], and its introduction is perhaps the most impressive that could be conceived." In the andante to the "Italian" Symphony Mendelssohn uses the soft notes of the middle register to produce a feeling of desolation, and by way of contrast gives very lively solo parts to the two flutes in the subsequent "Salterello."

Next to his use of the flute to produce an impalpable, sylph-like effect ("He brought the fairies into the orchestra and fixed them there."—Sir G.His use of

the Flute Grove), Mendelssohn's most outstanding feature in the treatment of the instrument is his use of rapid, iterated chords, often in triplets, on flutes and other wood-wind instruments—a device previously used by Bach, Beethoven, and Weber, and

Mendelssohn.—St. Paul, "Jerusalem."

Mendelssohn, Hymn of Praise, "Let all men praise the Lord."

![{\clef treble

\override Staff.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f %hide the automatic time signature

\override NoteHead.duration-log = #1

\autoBeamOff

g''8.[( a''])}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/c/o/cov3ut2tf552xtw74btphsjq6tn7wb0/cov3ut2t.png)

Mendelssohn seldom introduces the piccolo. The only instances I can find are the overtures Meeresstille;Piccolo in

Mendelssohn Loreley; the Military Overture, op. 24, for wind and drums only; and several times in the Walpurgis' Nacht. Strange to say, it is not used in Midsummer Night's Dream, where we might have expected it. He never employs more than one, or uses it above G′′′.

Schubert gives the flutes a good deal of solo work; sometimes he uses only one. The scherzo of the Ninth Symphony contains a delicious melody givenSchubert

and

Schumann to the flute: this was an afterthought. In the overture to Rosamunde von Cypern (op. 26) we find a remarkable scale passage for the flute alone. Important solo passages occur also in the overtures in Italian style and Des Teufel's Lustschloss. The Sixth Symphony (andante) has a Haydn-like passage for two flutes and two oboes; they are subsequently joined by the clarinet. He is skilful in contrasting the tone of the different wood-wind, and in the Rosamunde ballet music and entre-act makes the flute, oboe, and clarinet converse with one another in a most delightful manner. Schubert never uses the piccolo in his symphonies; but it is to be found in several of his (now-forgotten) operas, which also contain several important flute solos. As a rule he employs only the upper register of the flute, often ascending to the

Schumann, Symphony, No. 1, Cadenza.

Schumann for two flutes in unison with the violins. Schumann never uses the piccolo in his symphonies; but we find it in Paradise and the Peri (where one in D♭ is used in a difficult passage in D minor), and in several of his overtures. He rarely, if ever, uses the piccolo without the flute, but in his Concertstück for horns (op. 83) he gives it an independent melody whilst the flutes play chords.

The increased facility and the improvement in the instrument consequent on the introduction of the BöhmFlute in

Modern

Composers flute have caused modern composers to write very freely for it. They use it often as they would a violin, and think nothing of giving it passages or great technical difficulty, such as the earlier composers would never have dreamed of assigning to it. Moreover, the number used is systematically increased to three (Haydn, Gretry, and Meyerbeer had already occasionally introduced three), and sometimes a piccolo is used in addition. Quantz recommended that an orchestra should Include four flutes—the number found in the Berlin Hof-Kapelle in 1742—but he probably intended that the parts should be doubled. Thus Berlioz uses four flutes playing only two parts in octavesNumber

of Flutes

Increased in the march in his Te Deum (op. 22). In the "Agnus Dei" of his Great Mass for the Dead the four flutes play some chords of four notes, accompanied only by the trombones: here the fourth flute was not in the score as first written. I cannot recall any other orchestral example of four flutes playing four distinct notes. In the "Tibi omnes" the flutes have some wonderful arpeggios. In Berlioz's Funeral Symphony five flutes and four piccolos are directed to be used (the piccolos were originally in D♭ and the third flutes in E♭), but they all play in unison or octaves.

Berlioz was the only great composer (save Tschaïkowsky) who was himself a practical flautist. When a youth, his father bribed him to pursue his medical studies by the promise of a new flute with all the latest keys. Whilst quite a boy he wasBerlioz able to play Drouet's most difficult solos. In early life he composed two quintetts for flute and four strings, which he subsequently destroyed; but he afterwards used one of the themes in his Frane Juges. As a youthful student in Paris Berlioz gave lessons both on the flute and the guitar. In one of his letters he gives an amusing description of the usual style of prize compositions at the Conservatoire:—

The little birds wake; flute solo, violins tremolo.

The little rills gurgle; alto solo.

The little lambs bleat; oboe solo," and so on.

Berlioz makes frequent and delicious use of the flute, availing himself much of the low register; he employs the entire compass, right up to C in alt., as in Faust, in which work the flute has a fine running passage whilst the horn plays the melody. In L'Enfance du Christ weFlute and

Harp find an entire movement for two flutes and harp—a rather unique combination. Berlioz was very fond of writing for the flute or piccolo along with the harp; a notable example occurs in his arrangement of Weber's Invitation à la Valse. The combination appears to have been much favoured by the ancient Egyptians, and many modern composers have adopted it; amongst others, Mehul (Uthal), Mendelssohn (Antigone), Meyerbeer (Prophete and Stuensee overture), Adam (Si J'etais Roi), R. Strauss (Tod und Verklartung), Brahms (Requiem).[5] It is used by Wagner in The Rheingold (where the two instruments echo each other), in Lohengrin, and in The Walkure in a curious passage for two piccolos along with three harps answering each other.

Berlioz frequently combines the flute and oboe, sometimes giving the flute the lower part, an arrangement also found in Mendelssohn and Wagner (in Verdi's Requiem the flute plays below the clarinet). Noufflard, referring to the allegro in part two of thePiccolo in

Berlioz Fantastique Symphony, speaks of "le cri eperdu que jette une flute de son timbre strident." Berlioz uses the piccolo very frequently, employing it up to the top A′′′, and even B′′′♭, in the Funeral Symphony. In the "Apotheose" he combines two

Brahms, Requiem, No. 2.

piccolos and bassoons in a striking triplet passage. He allots the piccolo a very important passage along with the oboe in the Serenade in his Harold Symphony. In his "Pandemonium" (Damn. de Faust) we naturally have two piccolos, whilst in his "Heaven" we find three flutes and harps. He even uses the piccolo in the accompaniment to songs—e.g., The Danish Huntsman, "Meditation," in Cleopatra (where two are used), and the choral ballad, Sara the Bather.

Dvořák uses both the flute and piccolo with great skill. In his Third Rhapsody, and in the Second, Fourth, and Fifth Symphonies we find remarkable solos for the flute, whilst one of the most effective flute parts ever written is to be found in his lovely cantata, The Spectre's Bride. In this work he has allotted the instrument a most charming obligato toDvořák the principal soprano aria ("Oh, Virgin Mother"), in which he shows how fully he appreciated its lower register, going down to the lowest note. In his Stabat Mater and his Sclavonic

Dvořák, The Spectre's Bride, "Where art thou, Father?"

![\new Staff \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key aes \major

\time 3/8

\tempo "Andante con moto"

c,16( ees aes bes c ees

\autoBeamOff

aes)\pp r ees32([ d ees aes] ees8)

r des!32([ c des aes'] des,8)

\autoBeamOn

ces bes aes

ges des' fes,

ees d4

ees8 r r

\autoBeamOff

r ees''32([ d ees aes] ees8)

r des!32([ c! des aes'] des,8)

\autoBeamOn

ees16( aes ges ees ces fes)

ees( ces ges ces ees, ges)

aes4*1/2 \afterGrace bes4^\markup {\flat}\trill {aes16( bes)}

ces16( ges fes ees des! ces)

\autoBeamOff

ces32[ des! ees fes] ees[ des ces des] ees16 r

\afterGrace fes4.^\markup {\flat}\trill {ees32([ des)]}

ces32([ des! ees fes] ees[ des ces des] ees16) r

\autoBeamOn

\afterGrace fes4.^\markup {\flat}\trill {ees16( des)}

ees16( ges ces8.\< des!16

ges8\f ges,)\> r\! \bar "||"

\autoBeamOff

aes,32([ bes c des] c[ bes aes bes] c16) r

\afterGrace des4.\trill {c16([ bes)]}

aes32([ bes c des] c[ des c bes] aes16) r

\afterGrace des4.\trill {c16[ bes]}

c32([ ees aes bes] c[ bes aes g] aes[ f' d aes]

g[ ees' bes g] ees16)[ ees'\staccato ees\staccato ees]\staccato_"etc."

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/c/2c8ibot7094hc77671gz8trkll5chph/2c8ibot7.png)

Rhapsody he uses the low B—a note not found on most flutes—and in his Second Symphony the topmost C♮. In The Spectre's Bride he employs the flute to imitate the persistent crowing of the cock at sunrise, and also to depict the hero leaping over the wall (by a very rapid diatonic run from G′ to G′′). In "The Ride" the piccolo is used most effectively. In this work we also find a very elaborate cadenza, written, strange to say, for the second flute accompanying the voice.[6]

Grieg in his Peer Gynt Suite, No. 1 ("Morning"), has a quiet passage for solo flute, and later on in the same piece he writes gracefully forGrieg two flutes in thirds. In Olav Trygvason he uses two piccolos in thirds along with a flute in some effective chromatic runs, whilst in accompaniment

Grieg, Peer Gynt.

![\new Staff \with {

instrumentName = "FLUTE."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key e \major

\time 6/8

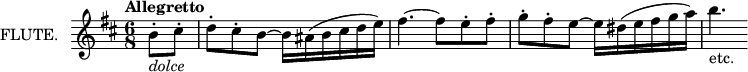

\tempo "Allegretto pastorale"

b'8(\p gis fis e fis gis)

\autoBeamOff

b([ \grace {gis16[ a]} gis8 fis] e[ fis16 gis fis gis)]

\autoBeamOn

\grace {gis16 a} b8(\< gis b) cis(\> gis cis)\!

b( gis fis e4) r8

}

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/i/q/iqddn4kg3eks1sgoce9oxveunqeytd2/iqddn4kg.png)

to his song Henrik Vergeland he assigns to the piccolo only four notes: the piccolo player here certainly earns his fee easily! In his Second Suite ("Danse Arabe") Grieg used two piccolos with drum and triangle.

The modern school of French composers make great use of the flute, frequently writing for it passages of delicate filigree and arabesques. They use the instrument "rather to ornament and brighten a subject thanModern

French

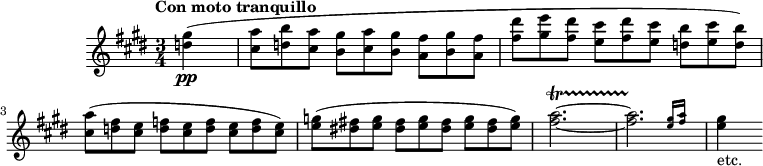

Composers to propound it." Sometimes, however, this degenerates into mere tinsel. Perhaps the most noticeable point about the modern use of the flute is the frequency of passages on the lower register, whose peculiar and unique beauty has been fully recognised by many recent composers. No one has more fully grasped the capabilities of the instrument than Bizet—who assigns the

Bizet, Carmen, Act III., Introductory March.

![\new Staff \with {

instrumentName = "FLUTE."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key ees \major

\tempo "Allegretto moderato"

\tweak text "bis."

\startMeasureSpanner

\autoBeamOff

\appoggiatura {aes16[ g f]} g4(\pp c8)[ r16 bes] g4~ g8 r

\stopMeasureSpanner

\appoggiatura {a16[ g f]} g4( c8)[ r16 bes16] g[\staccato bes\staccato ees\staccato g]\staccato bes4~

\autoBeamOn

bes16 aes!\staccato g\staccato f\staccato

ees\staccato d\staccato ees\staccato g\staccato

f( bes,) c\staccato d\staccato ees8 r

}

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

\context {

\Staff

\consists Measure_spanner_engraver

}

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/4/3/435w3ikis6pltazlzkehi5fe1x6vnra/435w3iki.png)

march in Act iii. of Carmen to the flute, playing staccato and pianissimo in the low register, with fine effect; so again in the Seguidilla, No. 10. Other fine flute passages in this work are the Entr'acte (ii.), where the two flutes play running passages in thirds along

Bizet, Carmen, Seguidilla, No. 10.

Bizet, Carmen, Act II., Opening. Zigeunerlied.

Bizet, Carmen, ii-iii. Zwischenspiel.

![\new Staff \with {

instrumentName = \markup \center-column {

"1st FLUTE."

"with Harp only."

}

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key ees \major

\tempo "Andantino quasi Allegretto"

\tupletUp

ees4.( f8 aes g f ees

bes'4 \tuplet 3/2 {c8 g c} bes4) r8 bes(

c d ees4)~ ees8 d( c g

\autoBeamOff

g[ bes \appoggiatura {f16[ g]} f8. ees16] f4 bes,)

\autoBeamOn

ees4.( f8 aes g f ees

bes'4 \tuplet 3/2 {c8 g c} bes4) r8 bes(

c d ees4)~ ees8 g( f ees

d c c d c bes c d

ees4) f8( g bes g f ees

d f c d \grace {c16 d} c8 bes f g

ees) r bes2( ees4)_"etc."

}

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/1/g/1glh4ioowwh55220mduj21zgqnvgvno/1glh4ioo.png)

with the harp, 'cello, viola; and the Zwischenspiel (ii.-iii.) for solo flute and harp only. In fact, throughout the entire work, the flutes are splendidly handled.

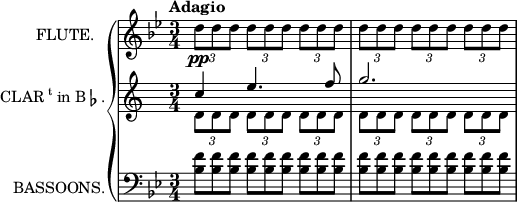

Turning to English composers of recent times, we find Sir Arthur Sullivan making great use of both the flute and piccolo in The Golden Legend.Modern

English

Composers The flute parts are written very high. At the beginning of this work he uses the flutes in sustained notes at the very top of their register to depict the whistling of the wind and the storm raging round the spire of the cathedral, and at the devil's words, "Shake the casements," he gives them a rapid staccato descending passage. The dying

Sullivan, Golden Legend. "Shake the casements."

away of the storm is portrayed by chromatic passages, gradually descending from the C♯ in altissimo, on the flutes. In the sixth scene there is the long passage for

Sullivan, Golden Legend, Sc. vi.

![\new GrandStaff <<

\new Staff = "top" \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key des \major

\time 3/4

\tempo "Andante tranquillo"

\ottava #1

<< {aes''2.\p} \\ {aes,2~ aes16 f' des ees} >>

<< {aes2 aes8. ges16} \\ {f ees aes, c des4~ des8. c16} >>

\autoBeamOff

<< {f[ ees des c]} \\ {des8[ aes]} >> <aes des>16[ aes bes aes] bes[ des c ees]

\autoBeamOn

<aes, des>( aes <aes aes'> aes \appoggiatura {c8} bes16 aes bes des c ees aes, <c ges>)

}

\new Staff = "bottom" \with {midiInstrument = "flute"} \relative c'' {

\key des \major

\time 3/4

\tempo "Andante tranquillo"

r1*3/4

r4 r16 aes'( f ges aes f des ees)

<< {f8.( ees16 f des ges f ges f ees f} \\ {d,2.~} >>

<< {f'16 ees f des ges f ges f ees4)} \\ {d,2.} >>

}

>>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/d/kdx9i9dame5ornr5rqrh8x23678orwg/kdx9i9da.png)

Sullivan, Golden Legend, Sc. i.

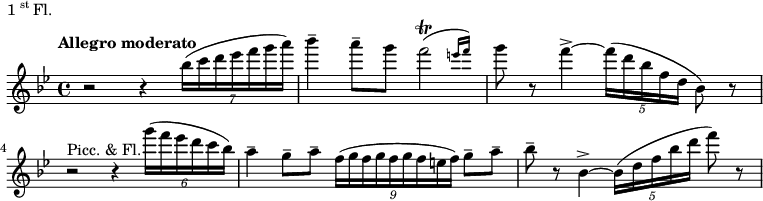

![\new GrandStaff <<

\new Staff = "piccolo" \with {

instrumentName = "2 PICCOLOS."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\transposition c'

\key e \major

\time 9/8

\tempo "Andante con moto"

\autoBeamOff

gis'16[\staccato\p^"Picc I." b\staccato e,\staccato gis\staccato cis,\staccato e]\staccato

b[\staccato e\staccato gis\staccato b]\staccato e,[\staccato^"Picc II." gis]\staccato

cis,[\staccato e\staccato a\staccato cis\staccato e,\staccato a]\staccato

gis b[^"Picc I." dis, gis cis, e] b[ e gis b] gis[^"Picc II." b] e,[ gis b e gis, cis!]

}

\new Staff = "flute" \with {

instrumentName = "2 FLUTES."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key e \major

\time 9/8

\tempo "Andante con moto"

b'16 <e, gis> b' <e, gis> b' <e, gis>

b' <e, gis> b' <e, gis> b' <e, gis>

cis' <e, a> cis' <e, a> cis' <e, a>

b' <e, gis> b' <e, gis> b' <e, gis>

b' <e, gis> b' <e, gis> b' <e, gis>

b' <e, gis> b' <e, gis> b' <e, gis>

}

>>

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/j/h/jhrdm1ig3g973kpb5rolb5dtuag3xod/jhrdm1ig.png)

latter answering each other in alternate phrases. In Coleridge Taylor's Hiawatha we find some most appropriate themes given to the flute. The work opens with an announcement of one of the principal motifs by a solo

Coleridge Taylor, Hiawatha.

flute, and the chief tenor solo has a delicate flute obligato. Some of the flute passages lie very high and are of great difficulty. A few can only be played with sufficient rapidity by the use of harmonics—a thing undreamt of by the older orchestral composers. Most of these, however, are doubled on the piccolo. This composer also gives a great number of shakes to the flute, including one of two and a half bars' duration on the top B′′′♮.

I have already spoken of Sullivan's use of the flutes in their highest register to depict a storm; WagnerWagner uses them for the same purpose in his overture to The Flying Dutchman, and also in the "Ride" in the Walküre, where he allots to the flutes chromatic runs and shakes on their very highest notes along with the piccolos. He uses the flutes in groups, generally employing three flutes (often in unison) and a piccolo, sometimes even more; thus in Siegfried (ii. 2) we find three flutes and a piccolo, but they play only three distinct parts, and in Tannhäuser we have in the orchestra three flutes (one also plays piccolo), and also on the stage four flutes and two piccolos. As a rule, Wagner uses his flutes chiefly in sustained or reiterated chord accompaniments, or in unison with the rest of the wind in forte passages. He is fond of combining them with the oboe (e.g., Tannhäuser, iii. 1, "The day breaks in," and in the Meistersinger several times). But he hardly ever gives the flute a solo of any length; practically never a really long solo standing out prominently. The flutes are never used absolutely alone for more than a single bar. In my examples I have given the nearest approaches to solo passages to be found in his works. In Siegfried and elsewhere he uses the three flutes to imitate the flutter of birds.

Wagner does not as a rule treat the flute as a melodic instrument, nor does he use it much for "conversations" between the various instruments. We often find whole pages of his scores with no flute or Wagner, Tristan. Beginning of Act II.

![\new Staff \with {

instrumentName = "FLUTE."

midiInstrument = "flute"

} \relative c'' {

\key bes \major

\numericTimeSignature

\time 2/2

f'2~(\p^\markup \center-column {\bold "Sehr" \bold "lebhaft"} f8 e ees d

\autoBeamOff

c[ bes] a4. c8 \tuplet 3/2 {bes[ g ees]}

\autoBeamOn

d des c g' f e bes' a)

g( ges f c' bes a ees' c)

<b f'>2~(\pp f'8 e ees d

<< {c bes a4 c \tuplet 3/2 {d8 g, ees}} \\ {fis2 g4~ g8 r} >>

d cis bes) r r2

}

\layout {

indent = 2\cm

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/3/y/3ysigaartohek9cqhkkbdbnkei68w64/3ysigaar.png)

Wagner, Götterdämmerung. Act III., sc. 2

![\new Staff \with {