The Story of the Flute/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V.

The Flute after Böhm

Various Patentees—Coche and Buffet—Ward—The Dorus Key—Siccama—Briccialdi's Lever—Carte's Flutes—Clinton—Pratten—Rockstro—Radcliff—Other Minor "Improvers."

The Böhm is the groundwork of all modern flutes. Since the inventor's day it has undergone many changes and experiments, but, with very few exceptions, these have not made any substantial improvement.Various

Patentees Böhm himself wrote in 1878, "Alterations can be made ad infinitum, but nothing has as yet been better than my system, which will very likely remain the best. I never dispute with others about their improvements." Between 1848–9 Messrs. Rudall and Rose alone made ten different attempts at "improvement" (all subsequently discarded) for various would-be inventors. Most of these attempts were based on no sound theory, others were merely new applications of old contrivances. If they remedied some old defects, they substituted other new ones. As Skeffington says, "Flute-players were divided, and flute-makers were worked up to a great pitch of rivalry and contention. Systems of mechanism were advocated which had really nothing at all of system in them; and theories were hastily laid down which were untenable on the commonest principles of science. . . . We have seen flutes sent forth with flaming titles and explanations based on acoustical theories and all sorts of scientific nostrums which were to astonish the orchestras of Europe, and we look round now in vain to see a single trace of their existence. . . . Any experimentalist, should he invent or alter but a single key, calls such invention a theory or system, and he attempts to show that the acoustical properties of the flute demand this key or this alteration."

The first of this "noble army of patentees" was Coche, who made one really valuable addition—namely, the hole and key for the C′′♯ D′′♯ shake—which is now put on all good flutes. Most of his modifications are ofCoche and

Buffet no practical value and have never become general. He adopted an excavation in the head-joint where it rests against the lower lip of the player, a device already suggested by Ribcock (c. 1782) and used by both Böhm and Gordon. It is still occasionally met with. Buffet fitted the keys with needle springs of steel wire (c. 1837), possibly at Coche's suggestion. These have since been universally employed on Böhm flutes. Strange to say, Böhm at first objected to them and would not use them, preferring the old flat brass springs. The needle springs were first used in England by Cornelius Ward in 1842. Ward was not satisfied with Böhm's flute. Accordingly in substitution for this "bungling compromise between tone, tune, and the ordinary dimensions of the human hand," Cornelius brought out a flute of his own, which was intended to remedy all Böhm's defects. Most of Ward's changes were adapted from earlier flutes; they are of an extremely minute and technical nature, aiming at an open-keyed system, and though they attracted a good deal of attention at the time, effected no real permanent improvement.Ward One peculiarity of Ward's flute was that the two low C keys were closed by the left hand thumb by means of long traction levers; this poor thumb had to work no less than five keys.

from left to right:

Fig. 1—Siccama's Diatomic Model (as Improved by Mahillon & Co.).

Fig. 2—Böhm's System (1847), as now made by Rudall, Carte & Co.

Fig. 3—Carte and Böhm Combined (1867 Patent) Model.

Fig. 13.—Briccialdi's B♭ Lever.

Carte,

& Co. the firm in 1850, was for many years well known as a flautist, possessing great facility of execution. In early life he was a personal friend of Spohr, and in 1842 was a member of Julliens' band. The improvements in the flute made from time to time by this firm are both numerous and important. In 1843 they took up Böhm's model of 1832, and brought over Grevé, one of Böhm's best workmen, to instruct their staff. When Böhm's model of 1847 appeared they at once adopted it (Page 68, Fig. 2). In 1851 Carte brought out a new patent flute, in which the open keys and equidistant holes

of Böhm were retained, combined with as much as possible of the old eight-keyed fingering, but a greater facility of rapid execution was obtained, chiefly by means of an open D hole for the second and third octaves, and less work thrown upon the thumb and little finger of the left hand, which are always weak. In 1867 Carte brought out another flute known as "The 1867 Patent Carte and Böhm Combined Flute" (Page 68, Fig. 3), which unites the advantages of the original Böhm with those of Carte's 1851 flute. The principal changes are in the key mechanism of the F♮ F♯ and B♮ B♭. It also affords a great variety of fingerings for each note.

Clinton in 1848 patented some quite useless modifications, reverting more or less to the old system of closedClinton keys, and contradicting much of what he had said two years previously. In 1855 he published a pamphlet about a new flute which he termed "The Equisonant Flute," retaining much of the old system of fingering, and having different diameters of the bore for the different notes to imitate the human larynx, a curious and valueless notion. A partisan of the Böhm thereupon asked if "equisonant" meant "equally bad all over," on which Mr. Rockstro remarks that unfortunately it was unequally bad! He next (1862) brought out a flute with cylinder body and equally graduated holes, getting smaller as they approached the mouth-hole. This flute, which gained a gold medal in the exhibition of 1862, was strongly advocated by Skeffington. It had not, however, even the merit of originality, as Böhm had tried graduating the holes before 1851, but had abandoned the idea. In 1863 Clinton patented yet another flute, to a great extent retaining the old fingering and closed holes.

Pratten tried various experiments, and about the year 1856 brought out his "Perfected Flute." He objected to take up the Böhm, and endeavoured toPratten adapt the old fingering to the cylinder flute with large holes, with the result that his flute had in the end seventeen keys in place of the original eight! It need hardly be added that this instrument did not justify its name, and is now completely relegated to oblivion.

Two other modifications of the Böhm which are still largely used deserve notice. R. S. Rockstro, after many attempts, in 1864 produced the modelRockstro known by his name. The principal features are the full adoption of the open-keyed system, the uniform diameter of the finger-holes, their increased size, and an extra F♯ key. Many of the keys are perforated. He subsequently placed a tiny tube at right angles at the C′′♯ hole to improve the tone. Mr. J. Radcliff also devised a new model—the nearestRadcliff approach to the old eight-keyed fingering. Its principal features are that it has not the open D, and that it has a closed G♯ also the B♭ key is closed by the first finger of the right hand by a separate lever. Radcliff advocates a mouth-hole which is almost square, such as Drouet used.

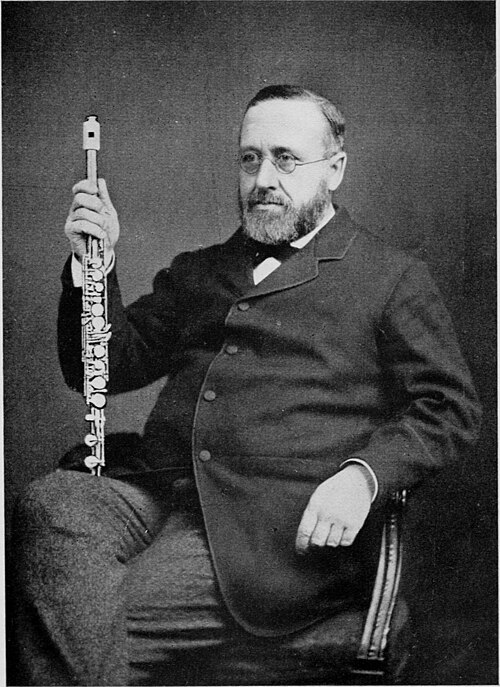

Mr. W. L. Barrett, Mr. Collard, Mr. Colonieu, and others have all brought out flutes with minute changes of fingering, etc. All these are very unimportant, and have not been generally adopted. The climax of tinkering was reached by Mr. James Mathews, aOther Minor

"Improvers" Birmingham amateur, whose flute had no less than twenty-eight keys! The tube was of gold, the keys of silver, and the head-joint of ivory, with a perfectly square mouth-hole. In fact, the whole instrument was "be-divelled," to use the expression of one who saw it. Mr. Mathews was a very fine player and an enthusiast. He founded the Birmingham Flue Trio and Quartett Society in 1856, of which Joseph Richardson was president till his death in 1862. The society possesses a magnificent library of flute music, including a Quartett specially written for it by Antonio Minasi.

After all, with the possible exception of Mr. Carte's 1867 Patent Flute, Böhm's own model is still the best:

The music, winding through the stops, upsprings

To make the player very rich."

—Mrs. Browning, Casa Guidi Windows.

James Mathews and his Flute, "Chrysostom."