The Theory and Practice of Handwriting/Chapter 8

CHAPTER VIII

ANALYSIS OF ALPHABET AND LETTERS

The English Alphabet is both written and printed in two kinds of letters– Capital and Small. In this chapter we are concerned solely with the written or Script Alphabet. So many diversified forms have been given and are at present in use for Script Capitals, and also, but in a much less degree, for small letters that it may be advisable to give a series of outlines, which shall contain as far as possible all the essentials of a clear bold and elegant simplicity, and shall at the same time, by the facility with which they are made, secure the highest possible rate of speed. On this series will be based the analysis which, so far as general elements can be grouped, arranges the letters for class instruction.

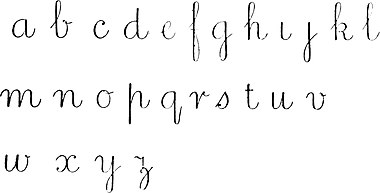

The small letters are

with the following duplicate forms ![]() which have a numerous following of ardent supporters. In selecting the outlines for our Capitals the aim has been to adopt as far as could be done the assimilations to the small letters whenever greater simplicity, ease or speed would be thereby attained.

which have a numerous following of ardent supporters. In selecting the outlines for our Capitals the aim has been to adopt as far as could be done the assimilations to the small letters whenever greater simplicity, ease or speed would be thereby attained.

The Capitals are

Fig. 28.

The variations on the above are simply legion, but it would be difficult if not impossible to find shorter outlines or plainer.

Returning to the small letters, they naturally group themselves into about eight classes which are fairly distinctive. For all teaching purposes this analysis will be found sufficiently elaborate in its gradation and scientific in its principle of arrangement.

Fig. 29.

Variations on the above scheme can be made without materially affecting the efficiency of the teaching.

Many eminent authorities for instance object to the early introduction of the long letters and there is admitted force in their objections. Naturally if we permit expediency to enter into the analysis the scientific aspect and character must suffer, at least to some extent.

Recognising however the strength of the arguments adduced, a second classification is offered which it is hoped will fully satisfy all requirements as to the gradual introduction of the long letters.

| Class I. | Class V. |

| |

| Class„ II. | Class„ VI. |

| |

| Class„ III. | Class„ VII. |

| |

| Class„ IV. | Class„ VIII. |

|

Fig. 31.

Class I.–The letters  consist solely of the right line and the final curve line, which is generally called a link, the dot of the i and the cross of the t not being constituent elements properly so called. As all words and combinations of letters are written continuously the letters of this class will join each other chiefly at the upper end.

consist solely of the right line and the final curve line, which is generally called a link, the dot of the i and the cross of the t not being constituent elements properly so called. As all words and combinations of letters are written continuously the letters of this class will join each other chiefly at the upper end.

A set of headlines on these three letters will begin with the right line, then the link should be introduced, lastly combinations of the character formed of the right line and link. Even at this early stage the teacher should endeavour to secure perfect rigidity of the down strokes, and strange as it may seem, such honest endeavour will generally be successful.

Class II. introduces but one new element viz. the initial curve cr as it is called the hook. Again but three letters compose this group one of which, p, will offer some difficulty because of its extraordinary length. Why should not English teachers introduce the custom so common on the Continent and begin the p at the top of the small letters instead of commencing it so far above them? It would be quite as legible and distinctive.

Fig. 33.

For our own part we much prefer the short stroke whether from a practical or an educational standpoint. The junctions in this group will principally be at the foot of the stroke and at or near the top, as shown in Fig. 34.

Fig. 34.

Exercises and Headlines on this and succeeding classes will of course contain abundant practice on all preceding letters and classes.

Class III. including the simple curved letters will require some care, the tapering strokes peculiar tobeing novel and not easy to accomplish. Blackboard illustration with a profuse series of varied headline copies will overcome every difficulty.

In forming the letter e the up stroke must never be broken but the up stroke from a preceding letter must be continued without any angular deflection into the loop of the e as shown in the diagram (Fig. 36).

Fig. 36.

With regard to the letter o it is begun on the top and not at the side which would necessitate a lifting of the pen.

Fig. 37.

Class IV. The three members of this class

Fig. 38.

are merely adaptations of elements previously given. There is a notion abroad that, since a and cognate letters are apparently made up of the letter o and other characters, consequently a perfect o must first be written before the remaining parts of the letters (a, d, g, and q). To restrict writing to any such arbitrary and rigid laws would be to greatly discount its highest function. And besides such rules are never observed in ordinary penmanship where utility will over-ride all such limiting and cramping regulations. What we must have is simplicity of outline, ease of junction and rapidity in tracing; it is therefore recommended that for purposes of continuity and speed the connecting upstrokes of these letters rise from the outside in large and set small hands, whilst for running or corresponding writing they rise from the inside.

Class V. brings us to the upward loop letters of which the simplest representatives are l and h. The loop as a rule forms half the extreme length of the letter although in small hand it is slightly longer. The loop should be well and boldly made particular care being taken to guard against the common danger and fault of curving the down strokes, as in the right-hand figure.

Fig. 39.

Inverting the loops we reach

Class VI. composed of

Fig. 40.

in which the same rules as to length apply so far as the loops are concerned. As previously stated the loops in all letters should be made sufficiently long for legibility, but not a fraction of an inch longer than is necessary to achieve that end.

As in the preceding class the greatest danger will be in the down stroke. It must be made absolutely right or straight.

When loops are curved an insipid and imperfect style is developed whereas when the rigid right lines are insisted upon; the writing becomes strikingly precise, nervous and pleasing.

Fig. 41.

Class VII. contains the crotchet letters

Fig. 42.

The crotchet is not hard to make and the open form is preferable to the closed style as it is made with greater ease and imparts more freedom to writing, although in very rapid caligraphy it resolves itself into a mere angle. Both kinds however are in constant use.

Class VIII. The five remaining letters of the alphabet which form this group have no principle in common, nor can they conveniently enter into any other class.

Fig. 43.

The letter s rises above the other small letters as does also the letter written in this form. The two following extremes of the s must be avoided.

X may be considered as formed of two c’s placed back to back the first being inverted. This letter has several modifications and it is the only letter that as a rule requires the pen to be lifted in its formation. Two of the modifications however are continuous although neither of them is very frequently met with.

F is a very long letter having two loops both of which should be boldly made as in Fig. 43.

Z is also totally unlike any of its fellows and will require separate treatment.

Ample practice should be afforded on these unique outlines.

Lastly the letter k comes in with its compound and difficult

Fig. 46.

curves. How often is it that we see a graceful or a nice-looking k? Very seldom indeed, and the four outlines in the adjoining figure are typical of the distortions that do duty for the genuine article.

The Capitals may be dismissed with but few remarks. They are made up primarily of Curves and it is the shape and several or relative sizes of these Curves that cause most trouble.

The characters should be analyzed on the blackboard and fully explained, the relation of the various parts being clearly defined and illustrated.

Afterwards the pupils may be left to imitate their headlines, careful supervision being all that is required. An approximate classification of the Capital letters is the only possible one, unless the divisions be unreasonably multiplied.

They may be arranged in the following order:

| Class I: | V, U, W, N, M, Y. |

| Class„ II: | O, A, C, G, E. |

| Class„ III: | P, B, R. |

| Class„ IV: | I, J, T, F. |

| Class„ V: | S, L. |

| Class„ VI: | D, H, Q, X, Z. |

This or some similar grouping of the Capitals should be followed that the instruction may be properly graduated, the scholars being specially urged to examine and imitate the engraved headline copies, for if the pupil succeed in securing a vivid mental conception of the true outline of any letter he will find little difficulty in transferring that conception to paper; the trouble as previously intimated is not so much with the fingers as with the brain.