Through the Earth/Chapter XXVII

CHAPTER XXVII

A SUCCESSION OF SURPRISES

ORGETTING the doctor's admonition not to touch the side of the car, our hero started himself on his upward journey by giving a strong jerk on the strap by the side of the car—one of the same straps, in fact, by means of which he had climbed to the ceiling before the start.

ORGETTING the doctor's admonition not to touch the side of the car, our hero started himself on his upward journey by giving a strong jerk on the strap by the side of the car—one of the same straps, in fact, by means of which he had climbed to the ceiling before the start.

But a strange surprise was in store for him; for, while by his pull upon the strap he sent himself traveling upward, the reaction pushed the car in the opposite direction, and it began slowly spinning around while our hero rose in the air.

William did not at first realize the true state of affairs. The idea that the car was turning did not at once occur to him, and he consequently imagined that the car was stationary, and that it was he himself who was spinning around. It was a natural illusion, and it was only dispelled when he noticed, in passing one of the instruments that denoted the position of the car in the tube, that the cylinder which represented the car was now placed obliquely in the glass tube, and was slowly turning. Then the truth of the matter flashed upon him.

"Well, here's something new," he remarked gleefully. "Not only can I spin myself around as I please, but I can also spin the car around, and make it revolve in any direction I wish."

As he said these words he reached the wall of the car, and the mere act of grasping the straps brought both him and the car to a stop.

"This does beat everything!" he exclaimed, highly pleased at the novel experience. "If I was like a fish in a basket before, I'm now more like a squirrel in a rotary cage, and could keep the car spinning around all day by climbing around the inside! At present, however, I'm not much in the humor for anything of the sort, especially as the car will present a slightly greater resistance to the air in the tube unless the point is kept perpendicularly downward. Besides, I'm still thirsty, and I want to get that drink."

So saying, William, little dreaming what was in store for him, quietly swam for the reservoir, and turned on the faucet; but, to his surprise, no water came out.

"H'm! this is pleasant," he said. "Dr. Giles must have forgotten to fill the reservoir."

Wishing to "make assurance doubly sure," he lifted off the cover, but in doing this left the faucet open, and also neglected to keep hold of the strap on the side of the car; and to these omissions he owed a new and rather disagreeable experience, for in his effort to lift off the lid he was obliged to use the side of the car as a point of resistance.

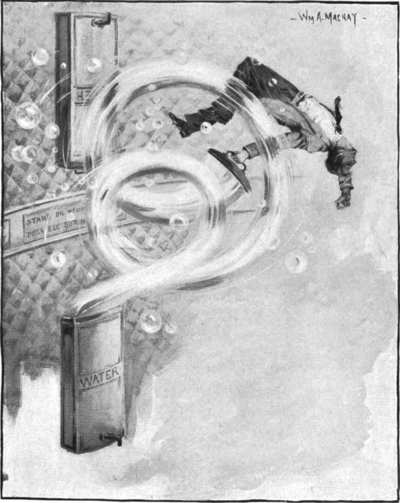

The consequence was that, when the cover did come off, the force of his exertions sent him flying through the air, still clutching the cover; and, as usual in his flights, he began spinning around, this time varying the monotony by turning his somersaults backward.

But this was not the worst of the matter, for, the faucet having been left open, the cover acted as a sort of piston, and sucked up all the water in the reservoir after it; and this water, accordingly, followed our hero in his strange flight, so that the poor boy was soaked through and through, while the water, by his violent movements, was scattered to all sides of the room as spray, and was either absorbed by the cushions, or rebounded from the instruments and came flying back, some portions of the liquid remaining suspended in glittering drops in mid-air, as though supported by invisible spider-webs.

But this was not all. Blinded and spluttering from his unexpected shower-bath, William did not notice just where he was going, and went crashing against one of the delicate instruments on the side of the car, breaking it into fragments.

This last incident brought him to his senses, and hastily grasping one of the straps, he brought himself to a stop, and tried to regain his composure.

"I wish Mr. Curtis was here now," he said to himself, grimly. "If he could look at that broken instrument, I guess he'd be satisfied that it does n't require weight to smash a glass globe.

"I see, too, what a fool I was when I set about getting that drink of water. I understand perfectly why it was the water did not run out of the faucet. The water, having no weight, could not, of course, be expected to run out. The law applies to liquids as well as to solids, that a body without weight will have no tendency to fall.

"I understand, also, how it was the water followed the cover of the reservoir and deluged me so

"THE FORCE OF HIS EXERTIONS SENT HIM FLYING THROUGH THE AIR."

This explanation was all very satisfactory, but it did not tend to quench our hero's thirst. There was, of course, enough loose water suspended in the car to enable him to get a good drink, if he were willing to swim after it, and swallow a few drops here and a few drops there, frog-fashion; but he was not much tempted to try this experiment. He had noticed a second reservoir of water, fastened upside down in the car for the convenience of passengers traveling from the New York side, and he therefore set to work to obtain a drink from this. He had, however, learned a lesson by experience, and reflected carefully before acting.

"Even if I could fill a tumbler with water," said he, "I should n't be able to drink it, as the water would n't run into my mouth. In fact, I'm not sure that, even after I get it into my mouth, I shall be able to make it run down my throat. If that's the case, then I'll be truly in the position of the ancient mariner, with plenty of water all around, yet never a drop to drink. Even if that is not the case, I shall have no easy task in getting the water into my mouth; in fact, the only possible way to accomplish this, that I see, is to suck it from the faucet."

This was, in reality, the easiest method at his command, and he had soon refreshed himself, for he found not the slightest difficulty in making the water pass down his throat. The feat was, in fact, the same as is frequently performed by jugglers, who quaff a tumbler of water while standing on their heads.

But William's passion for experimenting had not left him, and after he had drunk his fill, he swam slowly back from the faucet, without turning off the flow of water. As he had previously opened a vent in the cover, the pressure of the air from above forced the water out through the faucet into the vacuum formed, and the liquid accordingly followed our hero slowly, in the form of a long rope dangling from his mouth.

"WILLIAM WAS ABLE, BY BEING VERY DELIBERATE AND CAREFUL IN HIS MOVEMENTS, TO TIE IT UP INTO VARIOUS KINDS OF KNOTS."

Finally, when our hero tired of the sport, he wondered what to do with this water. By striking it in all directions it would, of course, be absorbed by the cushions, like the first lot; but he did not care to wet them any more than necessary, so he gathered up the mass of water in his hands, and slowly swam with it to the empty reservoir, and with considerable difficulty succeeded in putting it in and closing the cover again before it could escape.

It was really curious to be thus enabled to treat water almost as though it were a solid substance, the absence of weight rendering it so much easier for the mobile molecules to keep together!

Our hero's experiences with the water had proved so diverting that he now turned his attention to another experiment, which also promised to yield very amusing results.